Mordecai B. Hillel B. Hillel

From Jewish Encyclopedia (1906)

From Jewish Encyclopedia (1906) Mordecai B. Hillel B. Hillel:

German halakist of the thirteenth century; died as a martyr at Nuremberg Aug. 1, 1298. Mordecai belonged to one of the most prominent families of scholars in Germany, his grandfather Hillel being on the mother's side a grandson of Eliezer b. Joel ha-Levi, who again was a grandson of Eliezer b. Nathan. Little is otherwise known of his family. His wife Selda and his five children perished with him. About 1291 Mordecai seems to have sojourned at Goslar, where a certain Moses Tako—not the well-known anti-Maimonist—seems to have disputed his right of residence. Although the suit was decided in Mordecai's favor, it was conducted with such bitterness that it was probably for this reason that Mordecai left Goslar and settled at Nuremberg. His principal teacher was Meïr b. Baruch of Rothenburg, of whose older pupils Mordecai was one, and in whose presence Mordecai pronounced independent decisions. Mordecai quotes the tosafot, responsa, and compendiums of his teacher, together with many of his oral and written communications. Aside from Meïr must be mentioned as Mordecai's teachers Perez b. Elijah of Corbeille, Ephraim b. Nathan, Jacob ha-Levi of Speyer (probably identical with Jacob b. Moses ha-Levi), Abraham b. Baruch (Meïr of Rothenburg's brother), and Dan, probably identical with Dan Ashkenazi.

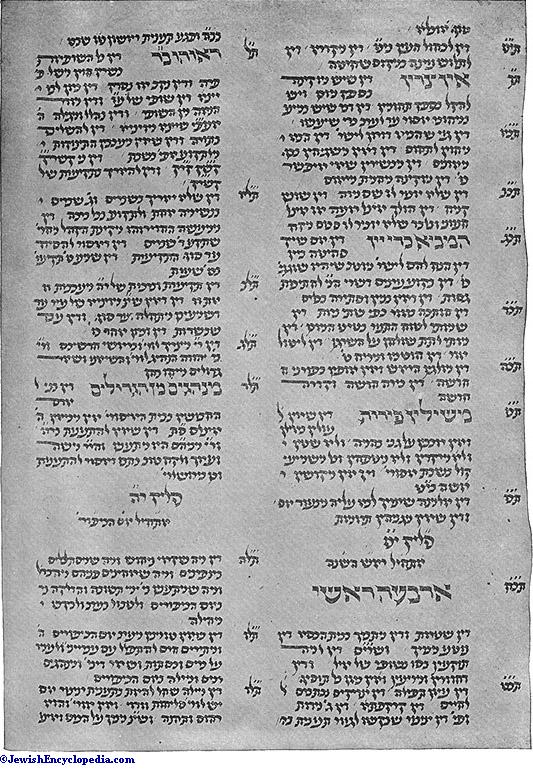

His Code.Mordecai is generally known as the author of the great legal code "Sefer ha-Mordekai," commonly called briefly "Mordekai," or designated as the "Great" or "Long Mordekai" ("Mordekai ha-Gadol," "Mordekai he-'Aruk") as distinguished from Samuel Schlettstadt's "Small Mordekai" ("Mordekai ha-Ḳaṭon"). The "Mordekai" is met with in the form of glosses to Alfasi's "Halakot" in various manuscripts, and also as an appendix to the "Halakot" in many editions. This connection with Alfasi is, however, merely an external one, single sentences, sometimes even single words, of the "Halakot" serving as catchwords introducing the relevant material found in Yerushalmi, the French and German tosafot, the codices and compendiums. Mordecai's range of reading in halakic literature was phenomenal. There were few noteworthy works dealing with halakic subjects and antedating the middle of the thirteenth century which he did not know and draw upon. As regards the German and French authors, he knew not only all the works that are still extant, but many for which he is now the only source. He quotes about 350 authorities, whose works and written or verbal communications form the substance of his book.

The Two Editions of "Mordekai."

The "Mordekai" is in the first place a compilation, intended to furnish halakic material. At the time of its composition there was great need for such a work. The results of the tosafist schools, whose last representatives were Mordecai's teachers, were ready to be summed up and judged. The condition of the German Jews of the time was such that they were forced to a life of constant wandering, and were in danger of losing, together with their worldly goods, their spiritual possessions if they remained hidden in numerous folios. It would be erroneous, however, to designate the "Mordekai" as a mere compilation. It not only contains much that is original with the author—although in many passages there are omissions of the names of authorities, due to copyist and editor—but the foreign material also is often introduced in a form which refutes the assertion that the author did not intend to contribute anything of his own. The "Mordekai" contains passages showing that the author had the ability as well as the intention to present in clear, systematic form, in the manner of a codifier, the results of long discussions (see the examples in Weiss, "Dor," p. 82). The fact that the larger part of the "Mordekai" lacks system and form may be explained on the following grounds: The book, as the early critics pointed out, was not issued in its final form by the author. He collected the material for his great work, but could not combine or arrange it himself; this task being undertaken by his pupils, partly during his lifetime and partly after his death. This fact explains not only the evident confusion of the text, but also its most peculiar history. Within two generations after Mordecai's death there were two entirely different recensions of his work, respectively designated by the authorities of the fifteenth century as the "Rhenish" and the "Austrian" versions. These were not merely two different copies of the "Mordekai" containing variants—such existed of each of the two editions—but two materially different compendiums. The Rhenish "Mordekai" furnished the text for the printed editions, and circulated during the Middle Ages not only in the Rhine countries, but also in eastern Germany, France, Italy, and Spain. The Austrian "Mordekai" is preserved in manuscript in the libraries of Budapest and Vienna. It exerted, as its name indicates, a great influence on the halakic observances of Austria, Moravia, Bohemia, Styria, Hungary, and the neighboring German provinces, as, for example, Saxony. The following points of difference between these two editions may be noted: The material is differently distributed, entire passages frequently being found in different sections and even in different treatises. The two editions are contrasted, too, in the method of treating the material. In the Rhenish "Mordekai" there is the endeavor to cut down and abbreviate, the printed work constituting only one-third of the matter found in the manuscripts of the Austrian "Mordekai" at Budapest and Vienna. Quotations and extracts from the different tosafot collections especially are missing in the printed book, whereas they are included in the manuscripts. The two versions, furthermore, differ greatly in their quotations from the authorities. Rhenish and French scholars are the chief authorities in the Rhenish version; but they are omitted in the Austrian, which substitutes Austrian authorities, Isaac Or Zarua', Abigdor ha-Kohen, and his father-in-law, Ḥayyim b. Moses, being especially frequently drawn upon. The Rhenish "Mordekai" is notable for its rigorous views. Opinions which interpret the Law leniently, especially those that disagree with the then obtaining practises, are either omitted entirely or are given in brief quotations and in a form which shows that they are not authoritative. The Austrian "Mordekai" gives these passages frankly and in detail. The conciseness and scrupulousness of the Rhenish version lead to the conclusion that the Austrian "Mordekai," as found in the manuscripts, represents the original form of the work, or at least most closely approaches that form which Mordecai intended to give to his book.

About sixty years after Mordecai's death Samuel b. Aaron of Schlettstadt wrote his "Haggahot Mordekai," glosses to the "Mordekai," consisting chiefly of extracts made by him from the Austrian version in order to supplement the Rhenish; and the text, which was already very corrupt and confused, was still further impaired by these glosses, as text and glosses were frequently confounded. While the "haggahot" are at least derived from the "Mordekai," there are passages in the printed text which have no relation whatever to that work. The "Small Halakot." ("Halakot Ḳeṭannot"), which figures in the editions as a part of the "Mordekai," is Schlettstadt's work, while the "Mordekai" to Mo'ed Ḳaṭan includes a complete work of Meïr b. Baruch of Rothenburg, and other extraneous elements have been introduced in different passages of the "Mordekai."

Diffusion of the "Mordekai."

In consequence of the persecutions in Germany during the fourteenth century and of the resulting decline of Talmudic studies, a work of the nature of the "Mordekai" naturally soon became authoritative. The high reputation enjoyed by it is evident from the works of Schlettstadt, which either deal with or are modeled upon it. The great authorities of Germany of the fifteenth century, as Jacob b. Moses ha-Levi (

), Israel of Krems, Isserlein, Jacob Weil, Israel of Brünn, and Joseph Colon, the greatest Italian Talmudist of that century, were great admirers of Mordecai, whose work they assiduously studied and whose authority they recognized. The first treatise of the Talmud that was printed (Soncino, 1482) included the "Mordekai" in addition to Rashi, the tosafot, and Maimonides. In Caro's and Isserles' codes Mordecai is among the authorities most frequently quoted. Isserles even lectured on the "Mordekai" in his yeshibah, many of his responsa being devoted to the questions of his pupils and friends regarding difficult passages of the book. In Italy and Poland, where the "Mordekai" was especially studied, a whole "Mordekai" literature came into existence. A large number of extracts, indexes, glosses, novellæ, and commentaries are still extant, the most important of these works being Joseph Ottolenghi's index, Baruch b. David's "Gedullat Mordekai," emendations of the text, and Mordecai Benet's commentary.

), Israel of Krems, Isserlein, Jacob Weil, Israel of Brünn, and Joseph Colon, the greatest Italian Talmudist of that century, were great admirers of Mordecai, whose work they assiduously studied and whose authority they recognized. The first treatise of the Talmud that was printed (Soncino, 1482) included the "Mordekai" in addition to Rashi, the tosafot, and Maimonides. In Caro's and Isserles' codes Mordecai is among the authorities most frequently quoted. Isserles even lectured on the "Mordekai" in his yeshibah, many of his responsa being devoted to the questions of his pupils and friends regarding difficult passages of the book. In Italy and Poland, where the "Mordekai" was especially studied, a whole "Mordekai" literature came into existence. A large number of extracts, indexes, glosses, novellæ, and commentaries are still extant, the most important of these works being Joseph Ottolenghi's index, Baruch b. David's "Gedullat Mordekai," emendations of the text, and Mordecai Benet's commentary.

Mordecai wrote also responsa, which, however, do not seem to have been preserved. S. Kohn ascribes to him the authorship of "Haggahot Maimuni"; but the ascription lacks support. It is noteworthy that Mordecai inclined toward poetry and grammar, a predilection that was rare in Germany at his time. A seliḥah by him, on the martyrdom of a proselyte, was published by Kohn ("Mordechai benHillel," Appendix, i.). But although Mordecai used Hebrew fluently and skilfully, he had no real poetical talent. A metrical poem of his on the Hebrew vowels—one of the few of this kind produced by the German Jews—was also published for the first time by Kohn ( l.c. ). The poem is obscure, the author apparently intending to speak in riddles. Mordecai wrote also a treatise in verse on the examination of slaughtered animals and on permitted and forbidden foods, which appeared under the title "Hilkot Sheḥiṭah u-Bediḳah we-Hilkot Issur we-Hetter" (Venice, 1550 ?). From the nature of the case the author could not confine himself to Biblical Hebrew; but his language is correct and fluent.

- Kohn, Mordechai ben Hillel, Breslau, 1878, reprinted from Monatsschrift, 1877-78;

- Steinschneider, Cat. Bodl. s.v.;

- idem, Hebr. Bibl. xviii. 63-66;

- Weiss, Dor, v. 80-81;

- Zedner, Cat. Hebr. Books Brit. Mus. s.v.

Categories: [Jewish encyclopedia 1906]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 09/04/2022 16:33:08 | 47 views

☰ Source: https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/10991-mordecai-b-hillel-b-hillel.html | License: Public domain

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed: KSF

KSF