Ruffed Grouse

From Nwe

From Nwe | Ruffed grouse | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Algonquin Provincial Park, Ontario, Canada

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Bonasa umbellus (Linnaeus, 1766) |

Ruffed grouse is the common name for a medium-sized North American [[grouse], Bonasa umbellus, characterized by mottled gray-brown or red-brown plumage, feathered lower legs, erectile black feathers on the sides of the neck of the ruff (collar of prominent feathers), and a fan-shaped tail with a distinctive black band. The male ruffed grouse is known for loudly drumming its wings, sometimes on a fallen log, to attract females. It is non-migratory.

Ruffed grouse play an important ecological role as part of food chains, consuming a wide variety of plant and animal matter (buds and twigs fo aspens, berries, insects, fungi, acorns) and being preyed upon by various birds of prey, such as the Northern goshawk (Accipter gentilis) and great horned owl (Bubo virginianus), and mammals such as the fox, fisher, and bobcat. The experience cyclical rise and fall of population over about a decade, similar to other animals, such as snowshoe hares.

Ruffed grouse are a prized target of sportsmen, who generally pursue them with shotguns. The difficulty of spotting a foraging or hiding grouse on the ground, given their protective plumage and the thick brush they often inhabit, and the starting burst when they are flushed and take to the air, adds to the allure for the hunter.

Overview and description

The ruffed grouse is one of about 20 species of grouse, which are plump, chicken-like, terrestrial birds comprising the family Tetraonidae of the order Galliformes. Grouse tend to be plump birds that have a protective coloration of mottled brown, gray, and red feathers, which cover the nostrils and partially or entirely cover the legs, with feathers to the toes.

Ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus) have a cryptic plumage with mottled gray, brown, black, and buff coloration and two distinct color morphs, gray and brown (or red) (Rusch et al. 2000). These two color morphs are most distinctive in the tails, with the gray morph having gray tails, and the brown morph being rufous (reddish-brown or brownish-red). In the gray morph, the head, neck, and back are gray-brown; the breast is light with barring. There is much white on the underside and flanks, and overall the birds have a variegated appearance; the throat is often distinctly lighter. The tail is essentially the same brownish gray, with regular barring and a broad black band near the end ("subterminal"). Brown-morph birds have tails of the same pattern, with rufous tails and the rest of the plumage much browner, giving the appearance of a more uniform bird with less light plumage below and a conspicuously red-brown tail. There are all sorts of intergrades between the most typical morphs. The gray color morph is more common in northern parts of the range and the brown color morph in the more southern parts (Rusch et al. 2000; Grzimek et al. 2004). All ruffed grouse except juveniles have the prominent dark band near the tip of the tail (Rusch et al. 2000).

Ruffed grouse have a tuft of feathers on the sides of the neck that can be erected into a ruff (Rusch et al. 2000). The ruff, which is a collar of prominent feathers, is on the sides of the neck in both sexes. Ruffed grouse also have a crest on top of their head, which sometimes lies flat. Both sexes are similarly marked and sized, making them difficult to tell apart, even in hand. The female often has a broken subterminal tail band, while males often have unbroken tail bands. Another fairly accurate sign is that rump feathers with a single white dot indicate a female; rump feathers with more than one white dot indicate a male.

Ruffed grouse range in size from about 43 to 48 centimeters (17-19 inches). Males and females are about the same size, with males averaging 600 to 650 grams (1.3-1.4 pounds) and females 500 to 590 grams (1.1-1.3 pounds) (Grzimek et al. 2004).

The ruffed grouse is frequently referred to as the "partridge" or as a "birch partridge." This is technically wrong, as partridges are unrelated phasianids (family Phasianidae). In hunting, this may lead to confusion with the gray partridge, a species that was introduced to North America from Europe and is a bird of open areas, not woodlands.

Distribution and habitat

The ruffed grouse is found in North America from the Appalachian Mountains across Canada to Alaska. It is found in Nova Scotia, Labrador and Newfoundland in eastern Canada, and as far south as norther Georgia in the eastern United States, while it is found south to California and Utah in the West (Grzimek et al. 2004). The ruffed grouse has a large range with an estimated extent of 8 million square kilometers (BI 2008).

The ruffed grouse is found in dry deciduous woodlands, Pacific Coast rainforest, and boreal forest (Grzimek et al. 2004). Mixed woodland rich in aspen seems to be particularly well-liked.

Behavior, diet, and reproduction

Like most grouse, ruffed grouse spend most of their time on the ground, and when surprised, may explode into flight, beating their wings very loudly. They tend to roost in conifers.

These birds forage on the ground or in trees. They are omnivores, eating buds, leaves, berries, seeds, and insects. According to Johnson (1995):

More than any other characteristic, it is the ruffed grouse's ability to thrive on a wide range of foods that has allowed it to adapt to such a wide and varied range of habitat on this continent. A complete menu of grouse fare might itself fill a book […] One grouse crop yielded a live salamander in a salad of watercress. Another contained a small snake.

In spring, males attract females by drumming, beating their wings loudly while in an upright position, often while on a fallen log, or perhaps roots or boulders. Drumming is done year round, but most intensely at dawn during the March to June mating period (Grzimek et al. 2004). The ruffed grouse also produces hissing, chirping, and peeping sounds, but is best known for these drumming sounds produced by the male (Rusch et al. 2000). The drumming sounds are produced by air rushing to fill the vacuum created under the wings as they are rapidly flapped, progressively faster, in front of the body (Rusch et al. 2000).

Females nest on the ground, typically laying 10-12 eggs (Grzimek et al. 2004). The incubation time is 23-24 days and chicks can fly at 10-12 days (Grzimek et al. 2004).

Conservation

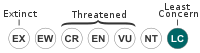

The ruffed grouse has a large continental population estimated in 2003 at 8,300,000 individuals (BI 2008). However, population densities across the continent have declined severely in recent decades, primarily from habitat loss. In Canada, the species is generally widespread, and is not considered globally threatened by the IUCN. Many states in the United States have open hunting seasons that run from September through January, but hunting is not considered to be a significant contributing factor in the population decline.

On the other hand, the ruffed grouse apparently absolutely requires significant tract of forest, at least part of which is older growth, to maintain stable population for any length of time. The species used to occur in Seneca County, Ohio and similar woodlands of the northern United States, but disappeared locally not long after most of these forests were cut down (Henninger 1906; OOS 2004). Isolated populations are prone to succumb to hunting; in Seneca County, the last recorded Ruffed Grouse of the original population was shot in the autumn of 1892 (OOS 2004). In addition, the species, like many grouse, undergoes regular population cycles of 10 to 12 years on average. Numbers of ruffed grouse increase and decline, not seldom by a factor of five, and occasionally by a factor of ten; the reasons are not well known.

Ruffed grouse are prolific and populations can be easily boosted by restocking. In some cases, even locally extirpated populations have been restored. Population cycles must be taken into account, so that restocked populations will have built up sufficient numbers before the downward cycle begins. Also, though in theory this species could sustain heavy hunting pressure because of its ability to produce many offspring, ample woodland must be present to allow sustained hunting without the risk of population collapse. It may well be that hunting is most efficient when population cycles are taken into account, granting the birds two years closed to hunting to recover from the lowest stock, and allowing far more than the usual numbers to be taken during bumper years.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- BirdLife International (BI). 2008. Bonasa umbellus. In IUCN, 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved December 19, 2008.

- Grzimek, B., D. G. Kleiman, V. Geist, and M. C. McDade. 2004. Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Detroit: Thomson-Gale. ISBN 0787657883.

- Henninger, W.F. 1906. A preliminary list of the birds of Seneca County, Ohio. Wilson Bull. 18(2): 47-60. Retrieved December 19, 2008.

- Johnson, D. L. 1995. Grouse & Woodcock: A Gunner's Guide. Krause Publications. ISBN 0873413466.

- Ohio Ornithological Society (OOS). 2004. Annotated Ohio state checklist. Version of April 2004. Ohio Ornithological Society. Retrieved December 19, 2008.

- Rusch, D. H., S. Destefano, M. C. Reynolds, and D. Lauten. 2000. Ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus). In A. Poole (ed.). The Birds of North America Online. Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved December 19, 2008.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 05:37:58 | 23 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Ruffed_grouse | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF