Gallipoli

From Nwe

From Nwe

The Gallipoli peninsula (Turkish: Gelibolu Yarımadası, Greek: Καλλίπολις/Kallipolis) is located in Turkish Thrace, the European part of Turkey, with the Aegean Sea to the west and the Dardanelles straits to the east. The name derives from the Greek Kallipolis, meaning "Beautiful City." Today the peninsula is part of the Turkish province of Çanakkale.

The peninsula and the strait, which was known in ancient times as the Hellespont, have always been of great strategic and economic importance as the gateway to Istanbul and the Black Sea from the Mediterranean.

The Gallipoli peninsula was the scene of one of the Allies' greatest military disasters of World War I and one of the Ottoman Empire's most costly victories. The Gallipoli battle incurred far-reaching consequences for both sides and was later the subject of an award-winning 1981 film that stresses the tragedy and futility of war.

Viewed from the perspective of a global trend toward societies opening to the workings of democratic principles of governance, the battle of Gallipoli was of central importance because through his role in the campaign, the Turkish leader of the opposing forces, Mustafa Kemal, gained such prominence that he became Ataturk, the father of modern, democratic Turkey.

History

Antiquity, Byzantium and crusaders

Kallipolis was a city in the southern part of the Thracian Chersonese (now known as the Gallipoli Peninsula), at the entrance of the Dardanelles strait, which in more ancient times was called the Hellespont, meaning "Helle's sea," in memory of Helle, a mythical Boetian princess. She was drowned in its swift waters after falling from the back of the legendary ram with the golden fleece.

The Hellespont was also the scene of the Greek legend of the two lovers Hero and Leander. Across the Hellespont from the eastern side, Leander swam nightly to visit Hero, a priestess of Aphrodite. Leander, too, drowned while attempting to swim across the Hellespont in a storm.

The Byzantine Emperor Justinian I fortified Kallipolis and established there very important military warehouses for grain and wine.

In 1304 the city became the center of a crusader state created by the Almugavares, or Catalonian routiers, who burned it in 1307, before retiring to Cassandria, (modern transliteration: Kassandra) in present-day Greece.

Ottoman era

Gallipoli was the first Ottoman conquest (c. 1356) in Europe and it was subsequently maintained as a naval base because of its strategic importance for the defense of Istanbul, lying 126 miles (203 km) to the west-southwest of the capitol. Gallipoli was also a key transit station on the trade routes from Rumelia (Ottoman possessions in the Balkans) to Anatolia. The city came into Ottoman possession after the devastating 1354 earthquake caused many Greeks to abandon the city, and Turks from Anatolia, the Asiatic side of the straits, swiftly reoccupied it, making Gallipoli the first Ottoman possession in Europe, and the staging area for their expansion across the Balkans.[1]

The Gallipoli peninsula, which was inhabited by populations of the Byzantine Empire, was gradually conquered by the Ottoman Empire starting from the thirteenth century onward until fifteenth century. The Greeks living there were allowed to continue their everyday life.

Gallipoli (in Turkish, Gelibolu) was made the chief town of a Kaymakamlik (district) in the province of Adrianople, with about 30,000 inhabitants—Greeks, Turks, Armenians and Jews.

By the eighteenth century Gallipoli had developed a reputation for its pottery, from which its modern name, Çanakkale (Turkish çanak, “pot,” and kale, “fortress”), is derived. Gallipoli became a major encampment for British and French forces in 1854 during the Crimean War, and the harbor was also a stopping-off point on the way to Constantinople. In European diplomacy of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, there was a recurrent controversy over restrictions on the passage of warships through the Bosporus, the Sea of Marmara, and the Dardanelles, which were the strategic straits connecting the Black Sea with the Aegean and Mediterranean seas.

During World War I Gallipoli was the scene of a critical battle as the Allies sought to find a way to reach their troubled ally, Imperial Russia, to the east.

Battle of Gallipoli

In Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Newfoundland, Gallipoli is the name given to the Allied Campaign on the peninsula during World War I, usually known in Britain as the Dardanelles Campaign and in Turkey as the Battle of Çanakkale. It was an Allied attempt to push through the Dardanelles and capture Constantinople (now Istanbul). Plans for such an operation were considered by Britain between 1904 and 1911, but military and naval opinion was against it. However, when war broke out between the Allies and Turkey early in November 1914, the plan was reexamined and classed as a hazardous, but possible, operation.

On January 2, 1915, in response to an appeal by Russia's Grand Duke Nicholas, commanding the Russian armies, Britain agreed to conduct an operation against Turkey designed to relieve pressure on Russia's Caucasus front, and to open an effective supply route to Russia. The German Empire and Austria-Hungary blocked Russia's land trade routes to Europe, while no easy sea route existed.

The Dardanelles was selected for a combined naval and military operation, which was strongly backed by the British First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill. An initial proposal was for an attempt to force the straits by naval action alone, using mostly obsolete warships too old for fleet action. This plan was modified, however, and it was agreed that the shores of the Dardanelles would have to be held by ground forces if the fleet passed through. For this purpose a large military force under British General Sir Ian Hamilton was assembled in Egypt, with the French also providing a small contingent.

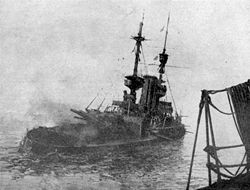

The naval bombardment began on February 16 but was halted by bad weather and not resumed until February 25. Demolition parties of marines landed almost unopposed, but bad weather again intervened. On March 18, the bombardment was continued; however, after three battleships had been sunk and three others damaged, the navy abandoned its attack, concluding that the fleet could not succeed without military help.

On April 25, 1915, as part of an allied force of British and French troops, Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) landed at Suvla Bay at the western end of the Peninsula (today officially called Anzac Cove).

Small beachheads were secured with difficulty, the ANZAC troops being held up by Turkish reinforcements under Mustafa Kemal, who later become famous as Atatürk. Large British and allied reinforcements followed, yet little progress was made. On August 6, another landing on the west coast, at Suvla Bay, took place, but after good initial progress the assault was halted.

The campaign's consequences

Following the failure of the August Offensive, the Gallipoli campaign entered a period of stalemate while the future direction was debated. The persistent lack of progress was finally making an impression in the United Kingdom.

In May 1915, the first sea lord, Admiral Lord Fisher, had resigned because of differences of opinion over the operation. By September 1915, it was clear that without further large reinforcements there was no hope of decisive results, and the authorities at home decided to recall Hamilton to replace him with Lieutenant General Sir Charles Monro. The latter recommended the withdrawal of the military forces and abandonment of the campaign, advice that was confirmed in November by the secretary of state for war, Lord Kitchener, when he visited the peninsula.

ANZAC forces were evacuated on December 19, 1915, and the other elements of the invasion force successfully evacuated by January 9, 1916. There were around 180,000 Allied casualties and 220,000 Turkish casualties. This campaign has become a "founding myth" for both Australia and New Zealand, and Anzac Day is still commemorated as a holiday in both countries. In fact, it is one of those rare battles that both sides seem to remember fondly, as the Turks consider it a great turning point for their (future) nation as well.

The campaign proved a catastrophe for Russia, and would eventually lead to civil war, the downfall of Imperial Russia and the Bolshevik revolution.

The Gallipoli campaign also gave an important boost to the career of Mustafa Kemal, who was at that time a little-known army commander but later was promoted to Pasha. Mustafa Kemal exceeded his authority and contravened orders in order to halt the Allied advance and eventually drive them back. His famous speech "I do not command you to fight, I command you to die" shows his courageous and determined personality. He went on to found the modern Turkish state after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire.

This campaign was also a major blow to the political prospects of Winston Churchill, then the First Lord of the Admiralty, and architect of the invasion plans. He resigned from the government and went to command an infantry battalion in France. In the end the military disaster hastened the resignation of Britain's Liberal prime minister H.H. Asquith, and his replacement by David Lloyd George, in December 1916.

More widely, the battle is regarded as a symbol of military incompetence and catastrophe.

ANZAC Day

On April 25, 2005, to mark the 90th anniversary of the Gallipoli landing, government officials from Australia and New Zealand, most of the last surviving Gallipoli veterans, and many Australian and New Zealand tourists traveled to Turkey for a special dawn service at Gallipoli. Prime Minister of Australia, John Howard, and the Prime Minister of New Zealand, Helen Clark were also in attendance, and Clark was accompanied by the official NZ defense force party, veterans of several past wars and ten New Zealand college students who won the New Zealand 'Prime Minister's Essay Competition' with their works about Gallipoli. Attendance at the ANZAC Day dawn service at Gallipoli has become popular since the 75th anniversary. Upwards of 10,000 people have attended services in Gallipoli.

Those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives… rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets where they lie side by side here… .

Mustafa Kemal

Until 1999 the Gallipoli dawn service was held at the Ari Burnu war cemetery at Anzac Cove, but the growing numbers of people attending resulted in the construction of a more spacious site on North Beach, known as the "Anzac Commemorative Site."

In 1934 Atatürk wrote a tribute to the ANZACs killed at Gallipoli. It is now inscribed at the ANZAC memorial at Anzac Cove:

Those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives…. You are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side now here in this country of ours… you, the mothers, who sent their sons from faraway countries wipe away your tears; your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land. They have become our sons as well.

Many mementos of the Gallipoli campaign can be seen in the museum at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra, Australia, and at the Auckland War Memorial Museum in Auckland, New Zealand.

Influence on the arts

The Battle of Gallipoli is the subject of a 1981 movie, entitled Gallipoli, directed by Peter Weir and starring Mel Gibson. It won nine awards, was nominated for a Golden Globe award and garnered four other nominations. The film emphasizes the futile sacrifice of Australian troops during the battle. It has been praised as one of the greatest anti-war films ever made, and criticized for ignoring the sacrifices made by other forces during the battle, especially those of the British.

The BBC produced a television series, All the King's Men, (not to be confused with the novel of the same name by Robert Penn Warren), that focused attention on a regiment (the "Sandringham Company") that was decimated at Gallipoli and which was composed of men who were servants at King George V's estate in Sandringham, Norfolk.

The campaign is also the subject of a 2005 documentary, also named Gallipoli, by the Turkish filmmaker Tolga Örnek, showing the bravery and the suffering on both sides through the use of surviving diaries and letters of the soldiers. For this film he has been awarded an honorary medal in the general division of the Order of Australia.

Notes

- ↑ Roger Crowley. The Holy War for Constantinople and the Clash of Islam and the West, 1453. (New York: Hyperion, 2005. ISBN 1401308503), 31.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Britannica DVD. Ultimate Reference Suite Encyclopedia. Brecon (UK): Bvg-Airflo Plc, 2004. ISBN 1593390858

- Crowley, Roger. The Holy War for Constantinople and the Clash of Islam and the West, 1453. New York: Hyperion, 2005. ISBN 1401308503

- Kinross, Patrick Balfour (Lord Kinross). Atatürk: A Biography of Mustafa Kemal, Father of Modern Turkey. New York: Quill, 1992. ISBN 0688112838

- Mango, Andrew. Atatürk: The Biography of the Founder of Modern Turkey. New York: Overlook Press, 2002. ISBN 158567334X

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Gallipoli history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of "Gallipoli"

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 01:26:53 | 11 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Gallipoli | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed: KSF

KSF