Battle Of The Philippine Sea

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia The Battle of the Philippine Sea in June 1944, was a major defeat inflicted by the United States Navy on the Imperial Japanese Navy in World War II. Japan lost almost 400 planes and three aircraft carriers in two days of fighting, while American losses were light. It marked the end of offensive Japanese capabilities, and gave the U.S. control of Guam, Saipan and Tinian islands that provided air bases within range of B-29 bombers targeted at Japan's home islands. It was entirely an air battle, in which Americans had all the technological advantages. It was the largest naval battle in history, to day, surpassed only by the Battle of Leyte Gulf four months later.

Contents

Plans[edit]

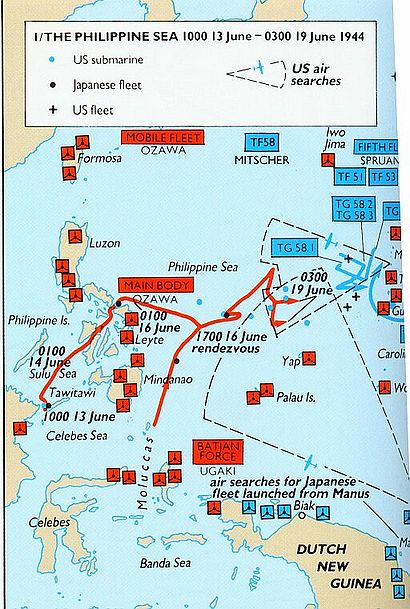

In strategic terms the US Navy began a long movement across the Pacific, seizing one island base after another. Not every Japanese stronghold had to be captured; some, like the big bases at Truk, Rabaul and Formosa were neutralized by air attack and then simply leapfrogged. The goal was to get close to Japan itself, then launch massive strategic air attacks and finally an invasion. The US Navy did not seek out the Japanese fleet for a decisive battle, as Mahanian doctrine would suggest; the enemy had to attack to stop the inexorable advance. The climax of the carrier war came at the Battle of the Philippine Sea. Airfields on the island of Saipan—within B-29 range of Tokyo—was the objective as 535 ships began landing 128,000 Army and Marine invaders on June 15, 1944. The achievement in planning such a complex logistical operation in just ninety days, and staging it 3,500 miles from Pearl Harbor was indicative of American logistic superiority. (The previous week an even bigger landing force hit the beaches of Normandy—by 1944 the Allies had resources to spare.)

The Japanese Navy decided to commit itself to a decisive battle along the lines of Alfred Thayer Mahan's theories of a decisive fleet battle. They thought the new air groups they had trained were ready for combat. (Most of the old Japanese carrier complements had been destroyed in the defense of Rabaul.)

The plan was to bait the American Fifth Fleet, led by Admiral Raymond Spruance to advance into Japanese waters, where Japanese submarines, carrier-based planes and land-based planes could destroy the Americans.

Forces[edit]

The fleet lineup was thus:[1]

Japanese:

5 fleet carriers

4 light carriers

5 battleships

11 heavy cruisers

2 light cruisers

28 destroyers

440 aircraft (carrier-based), 100-200 aircraft (land-based)

Americans:

69 destroyers

900 aircraft

Ozawa's strategy[edit]

Japan had to save Saipan—the only possible defense was to sink the 5th Fleet covering the landing, a fleet with 15 big carriers and 956 planes, plus 28 battleships and cruisers, and 69 destroyers. Tokyo sent Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa with nine-tenths of Japan's fighting fleet—it was about half the size of the American force, and included nine carriers with 473 planes, 18 battleships and cruisers, and 28 destroyers. Ozawa's pilots boasted of their fiery determination, but they had only a fourth as much training and experience as the Americans. They were outnumbered 2-1 and used inferior equipment. Ozawa had anti-aircraft guns but lacked proximity fuzes and good radar.

With the odds stacked against him, Ozawa had to gamble on surprise and a trick strategy. His planes carried more gasoline because they were not weighted down with protective armor; they could attack at 300 miles, and could search a radius of 560 miles. (The high speed and maneuvering at the attack scene consumed gasoline rapidly, and accounts for the difference.) The heavier Hellcats could only attack to 200 miles, and only search to 325. Ozawa's plan therefore was to use his advantage in range by positioning his fleet 300 miles out, forcing the Americans to search over 150,000 square miles of ocean just to find him. The Japanese ships would stay beyond American range, but their planes would have enough range to strike the American fleet. They would hit the carriers, land at Guam to refuel, then hit the Yankees en route back to their carriers. Ozawa counted heavily on the 500 or so ground- based planes that had been flown ahead to Guam and other islands in the area. He hoped that a few "lucky" hits like those at Midway would do the job.

Spruance's strategy[edit]

Spruance was in overall command of the 5th Fleet. A brilliant long-range strategist, in battle he was highly cautious and inflexible once he had made up his mind. A battleship sailor, he still did not fully appreciate the power of his carriers. The Japanese plan would have failed if the much larger American fleet had closed on Ozawa and attacked aggressively; Ozawa had the correct insight that the unaggressive Spruance would not attack. Admiral Mitscher, in tactical command of the Task Force 58, with its 15 carriers, was aggressive but Spruance vetoed Mitscher's plan to hunt down Ozawa because Spruance's personal doctrine made it his first priority to protect the soldiers landing on Saipan. Spruance still did not understand the new carrier doctrine, and he did not realize that Ozawa was a Mahanian looking for a decisive battle that would destroy the American carriers.

The battle[edit]

Ozawa had scout planes out, and they sighted the American task force on the afternoon of the 18th. Many of his officers wanted to attack immediately, but Ozawa decided against it, since the attack planes would not arrive at their land bases until evening had fallen, forcing his inexperienced fliers to land in the dark. Since the Amrericans hadspotted the scout planes, Mitscher knew the enemy was in the area and had time to prepare.

The forces converged to the largest sea battle ever fought to date. Ozawa's strategy worked to perfection—on paper; in real water and fresh air it disintegrated. Over the previous month American destroyers had depth charged 17 of the 25 submarines Ozawa had sent ahead. Repeated raids destroyed the Japanese land planes based on Guam and wrecked the airfields.

The Marianas Turkey Shoot[edit]

When Ozawa finally launched, his strategy already was in ruins. His cleverness outdid itself, for at such long range the attackers straggled in, allowing the Yankees to take patient aim and knock them down one at a time. If they had arrived simultaneously it might have been a real battle. Following Nimitz's directive, the carriers all had combat information centers that performed brilliantly. They interpreted the flow of radar data instantaneously and radioed orders to the Hellcats to intercept the bandits 50 or 60 miles out. The few surviving attackers encountered massive American antiaircraft fire with proximity fuzes.

The attack began the next morning, with the first wave of 64 planes. The American Hellcats and surface ships were waiting for them, and 42 were shot down. All the Japanese had accomplished in return was a bomb hit on the battleship South Dakota, which killed 23 men and injured 27, but did no serious damage.

More attacks followed. A few planes of the second wave did manage to get through to the American carriers, but scored only near misses on the Wasp and Bunker Hill (which suffered some minor shrapnel damage).[1] The third and fourth waves had a similar lack of success, and suffered heavy losses. Some Hellcats also took part in afternoon strikes on the Japanese airfields where Ozawa’s planes were to land, and the Japanese suffered more losses in those battles. All told, out of 373 planes launched from Ozawa’s carriers, 243 were shot down, with about 30 others severely damaged. Including the strikes on land bases, the Americans had destroyed almost 300 enemy aircraft, for the loss of 17 Hellcats and eight bombers.[2] One pilot remarked that it was "just like an old time turkey shoot", and the name stuck.

It was a stunning performance. Over a period of eight hours one American warship was slightly damaged while one Japanese plane burst into flames every two minutes.

Day Two[edit]

On the second day American scout planes finally located Ozawa's fleet at 275 miles; submarines sank two of his carriers. Mitscher launched 230 torpedo planes and dive bombers to attack immediately. He then discovered that the enemy was actually another 60 miles further off—out of round-trip range. Unless he recalled his planes it was unlikely that his pilots would make it back. Mitscher was a fighter who believed in the new carrier doctrine; he did not recall the planes. The attack was successful, sinking the light carrier Hiyo and two oilers, and damaging the carriers Zuikaku, Chiyoda, Junyo, and the battleship Haruna. Escorting fighters also shot down more Japanese planes. Twenty American planes were shot down, but 80 crashed on the way back for lack of fuel. Thanks to heroic effort and precise sea rescue technique, all but 50 of the aircrew survived. (The Japanese by contrast generally ignored their downed pilots.)

Spruance has been sharply criticized and stoutly defended for a doctrine that allowed Ozawa's six remaining carriers to escape; if he had been more aggressive they might have been sunk. But superior resources and training won out. The US lost 130 planes and 76 men in one of the greatest victories in world naval history. Japan lost 450 planes, three carriers and 445 of its best remaining pilots. Saipan was lost and soon bulldozers were clearing super-long airfields for the Superfortress, the B-29 bombers now in range of Tokyo.

Top Guns[edit]

The highest-scoring pilot of the day was David McCampbell of the USS Essex, future Medal of Honor winner and top-scoring Navy fighter pilot of the war. McCampbell had two kills from earlier in the campaign, and downed five “Judy” dive bombers that morning to become an ace. He shot down two Zeroes later that day during an afternoon strike on Guam.

Alex Vraciu of the USS Lexington, the top-ranked Navy ace at the time with twelve victories, downed six Judys of the second wave in about eight minutes. When he returned to the carrier, a picture was taken of him next to his Hellcat holding up six fingers and grinning like a madman. This picture became one of the most famous to come out of the battle. It was later found that Vraciu had expended 360 rounds in the action, or ten rounds for gun per kill. He was awarded the Navy Cross for this action.

Ensign Wilbur “Spider” Webb, a recent transfer to fighters from bombers, became an ace in a day in the Turkey Shoot when he attacked a flight of Aichi dive bombers over Guam, downing six. Webb returned safely to his carrier, the Hornet, but the bomber gunners had shot his plane so full of holes that it was judged a total loss.[3]

Submarine Successes[edit]

Meanwhile, distance was keeping the Japanese carriers safe from American aircraft, but American submarines were another matter. Some of the submarines that had been tracking Ozawa’s fleet for Spruance now chose targets and attacked. The Albacore scored only a single torpedo hit on the new fleet carrier Taiho, but that was enough, as fires set by the explosion ignited fumes from a burst fuel line, causing enough damage to sink the ship. At the same time, the submarine Cavella hit the Shokaku, a veteran of Pearl Harbor, with three torpedoes, sinking her three hours later.[4]

Bibliography[edit]

- Buell, Thomas. The Quiet Warrior: A Biography of Admiral Raymond Spruance. (1974).

- Morison, Samuel Eliot. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. 8, New Guinea and the Marianas. (1962), official U.S. Navy history

- Spector, Ronald. Eagle Against the Sun: The American War with Japan (1985); brief summary excerpt and text search

- Tillman, Barrett. Clash of the Carriers : The True Story of the Marianas Turkey Shoot of World War II (2005) 368pp excerpt and text search

- Toland, John. The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire, 1936-1945 (1970); Pulitzer Prize history from Japanese perspective; excerpt and text search

- Y'Blood, William T. Red Sun Setting: The Battle of the Philippine Sea (2003)

References[edit]

- ↑ USS Bunker Hill (CV-17)

- ↑ Aircraft of World War II in Combat, ed. by Robert Jackson, Amber Books, 2008

- ↑ Barrett Tillman, Clash of the Carriers: The True Story of the Marianas Turkey Shoot of World War II, (2005)

- ↑ Helmut Pemsel, A History of War at Sea, Naval Institute Press, 1975

Categories: [United States Navy] [World War II Battles] [Naval Battles]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/11/2023 10:24:22 | 16 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Battle_of_the_Philippine_Sea | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF