Thai Art

From Nwe

From Nwe

Traditional Thai art was heavily influenced by Buddhist and Hindu traditions brought from India and neighboring countries by various empires and ethnic groups. By the mid-thirteenth century, a unique Thai style, which flourished in northern Thailand during the Sukhothai (1238 – 1438) and Ayutthaya (1350 – 1767) periods, had developed. Buddhism was the primary theme of traditional Thai sculpture and painting, and the royal courts provided patronage, erecting temples and other religious shrines as acts of merit or to commemorate important events. Much of the Thai cultural heritage was damaged or destroyed when the Burmese sacked Ayutthaya in 1767, and the first three kings of the Chakri dynasty devoted themselves to salvaging, restoring and reinvigorating the old traditions. In the nineteenth century, Thai art began to show evidence of Western influences. Contemporary Thai art often combines traditional Thai elements with modern media and techniques, and encompasses some of the most diverse and versatile art in Southeast Asia.

In ancient Thailand, as in most parts of Southeast Asia, artists typically followed the styles and aesthetic conventions of their era and works of art were produced as acts of religious merit, not for individual recognition. There was little distinction between “artisan” ("chang feemeu"), and “artist” ("silapin"). Traditional Thai sculpture, painting and classical dance drama was primarily religious. Thai art encompasses a number of other media including architecture, textiles, and ceramics.

Overview

The history of the area that comprises the modern nation of Thailand is a history of different empires and different ethnic kingdoms, flourishing in different areas and at different times. These included the Srivijaya Kingdom (3rd – 13th centuries) in South Thailand, the Dvaravati Kingdom of the Mon people (sixth – eleventh centuries) in Central Thailand, the Haripunchai Kingdom (750 – 1292) in North Thailand, the Khmer Cambodian Empire (ninth – thirteenth centuries) over most of Thailand, and the Tai Kingdoms: the Lanna Kingdom (1296 – 1899), the Sukhothai Kingdom (1238 - 1438), the Ayutthaya Kingdom (1350 – 1767), the Taksin Kingdom (1768 – 1782, also known as the Thonburi Kingdom) and the Chakri Kingdom (1782-present).[1] Each of these kingdoms had its own artistic traditions, strongly influenced by Buddhist and Hindu traditions brought from India and neighboring countries. By the mid-thirteenth century, a unique Thai style, which flourished in northern Thailand during the Sukhothai (1238 – 1438) and Ayutthaya (1350 – 1767) periods, had developed. Buddhism was the primary theme of traditional Thai sculpture and painting, and the royal courts provided support for the arts, erecting temples and other religious shrines as acts of merit or to commemorate important events such as an enthronement or a victory in battle.[2]

In ancient Thailand, as in most parts of Southeast Asia, there was little distinction between “artisan” ("chang feemeu"), and “artist” ("silapin"); artists typically followed the styles and aesthetic conventions of their era and works of art were produced as acts of religious merit, not for individual recognition.[2] Until the early modern period, Thai craftsmen were considered "true artists," possessing superior intellect and wisdom, and a thorough understanding of culture. The creative powers of individual artists were embodied in stylized objects created for use in Thai society and religious practice.[3] During the nineteenth century, Western influence introduced the concept of the artist as an individual, and of producing works solely for visual enjoyment or as an expression of personal or political values.

Prehistoric Thai art

Evidence of bronze and iron tools from 2500 to 1500 years old has been found at sites in Lamphun and Chiang Mai Provinces. The Hoabinhian hunters and gathers inhabited the Chao Phraya Valley and left pieces of pottery with a wide range of decorative designs. Later Neolithic settlements associated with rice cultivation are concentrated in two parts of Central Thailand.[4] Caves and scarps along the Thai-Burmese border, in the Petchabuan Range of Central Thailand, and overlooking the Mekong River in Nakorn Sawan Province, contain galleries of rock paintings.

Artifacts found at the Ban Chiang archaeological site in northeastern Thailand, discovered in 1966 and dating from about 2100 B.C.E. to 200 C.E., include attractive red painted pottery with unique designs applied to the surface, crucibles and bronze fragments, and bronze objects such as bracelets, rings, anklets, wires and rods, spearheads, axes and adzes, hooks, blades, and little bells.

Painting

Traditional Thai paintings primarily consist of book illustrations and painted ornamentation of buildings such as palaces and temples. The most frequent narrative subjects for paintings were the Ramakian (the Thai version of the Hindu epic, the Ramayana); the Jataka stories; episodes from the life of the Buddha; the Buddhist heavens and hells; and scenes of daily life. The manuscripts and scriptures of Theravada Buddhists were in Pali, an Indian language which could only be understood by the educated elite. Murals were intended to educate monks and the general public about the events of Buddha’s life, history, moral lessons, and the Buddhist cosmology. Murals found throughout Thailand depict the idyllic Himaphan Forest, the mythical region of the Universe associated with the Himalayas, populated with celestial beings and stylized imaginary creatures, some part human and part animal or bird.

Traditional Thai paintings showed subjects in two dimensions without perspective. The size of each element in the picture reflected its degree of importance. The primary technique of composition was that of apportioning areas: the main elements are isolated from each other by space transformers, eliminating the intermediate ground, which would otherwise imply perspective. Perspective, and the use of shading to create depth, was introduced only as a result of Western influence in the mid-nineteenth century.

Thai murals contain many individual scenes, landscapes and figures, small in contrast to the large wall space on which they are painted. All the panoramas, whether they are located at eye level, near the floor, or above the viewer’s head, are painted as though seen by an observer looking down from the sky high above them. Events of religious and everyday life from different times are depicted simultaneously, separated by landscapes or architecture. Celestial and or noble beings are always portrayed as smooth, graceful and serene, while the common folk are painted in realistic or comic, ungainly postures and movements.<ref=mural/>

Srivijaya art

The term "Srivijaya art" can be used to refer to all art and architecture in South Thailand during the period from the seventh - thirteenth centuries. The Srivijaya Kingdom was ruled by the Sailendra dynasty of Central Java, which also ruled the Indonesian Archipelago, the Malay Peninsula and Southern Thailand to the Isthmus of Kra. Sculpture and architectural relics from this period confirm that Mahayana Buddhism was predominant, and reflect various infusions of style from India (Amaravati, Pala and Gupta), Champa (Vietnam) and central Java. From the eleventh century, influences of Khmer art were also evident.[5]

Dvaravati art

“Dvaravati art” refers to the art style that dominated in Thailand during seventh – eleventh centuries, before the arrival of the Khmers and later the Tai. Dvaravati also refers to the Mon communities that ruled what is now Thailand. The Dvaravati kingdom existed from the sixth to the eleventh centuries before absorbed by the growing Lavo and Subharnaburi kingdoms. The people of the kingdom used the ancient Mon language, but whether they were ethnically Mon is unknown. There is evidence that this kingdom may have had more than one race, including Malays and Khmer. The “kingdom” may simply have been a loose gathering of principalities rather than a centralized state. Nakhon Pathom, U Thong and Khu Bua in Central Thailand are important sites for Dvaravati art and architecture.

Dvaravati itself was heavily influenced by Indian culture, and played an important role in introducing Buddhism and particularly Buddhist art to the region. During this period, the various styles seen in later Thai art began to develop. Stone sculpture, stucco, terra cotta and bronze art objects are of Hinayana Buddhist, Mahayana Buddhist and Hindu religious subjects. Paintings featured people, dwarfs and animals, particularly lions. The style shows influences from India, Amaravati (South India) and Gupta and post-Gupta prototypes (fourth – eighth centuries in India). In India, Buddhist clerics had standardized 32 features to be included in any representation of the Buddha, so that all his images would be instantly recognizable. The Buddha was portrayed as having an aura of inner peace, with a profound spiritual purity. The Hindu Gods, Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva, were depicted as kingly super-humans radiating power, with strong and beautiful faces, crowned and adorned with jewels. Their consorts were the embodiment of feminine grace and sweetness. Early images had Indian faces, but later works had local elements such as Southeast Asian facial features. The distinctive Dvaravati Sculptures of the Wheel of Law, the symbol of Buddha’s first sermon, were erected on high pillars and placed in temple compounds throughout the Dvaravati Kingdom.[6]

During the tenth century, the Theravada Buddhism and Hindu cultures merged, and Hindu elements were introduced into Thai iconography. Popular figures include the four-armed figure of Vishnu; the garuda (half man, half bird); the eight-armed Shiva; elephant-headed Ganesh; the naga, which appears as a snake, dragon or cobra; and the ghost-banishing giant Yak.

Sukhothai period (1238 – 1438)

By the thirteenth century, Hinduism was declining and Buddhism dominated much of Thailand. Buddha images of the Sukhothai (“dawn of happiness”) period (1238 - 1438, northern Thailand) are elegant, with sinuous bodies and slender, oval faces. Sculpture was inspired by Theravada Buddhism which created a new style in which spiritual serenity is merged with human form. Intended to reflect the compassionate and superhuman nature of the Buddha, the images did not strictly follow the human form but followed interpretations of metaphors from religious verse and Pali language scriptures. The omission of many small anatomical details emphasized the spiritual aspect of the Buddha. The effect was enhanced by casting images in bronze rather than carving them.

Sukhothai artists followed the canonical defining characteristics of a Buddha, as they are set out in ancient Pali texts:

- Skin so smooth that dust cannot stick to it

- Legs like a deer

- Thighs like a banyan tree

- Shoulders as massive as an elephant's head

- Arms round like an elephant's trunk, and long enough to touch the knees

- Hands like lotuses about to bloom

- Fingertips turned back like petals

- head like an egg

- Hair like scorpion stingers

- Chin like a mango stone

- Nose like a parrot's beak

- Earlobes lengthened by the earrings of royalty

- Eyelashes like a cow's

- Eyebrows like drawn bows

The "walking Buddha" images developed during the Sukhothai period are regarded as its highest artistic achievement. These stylized images, which do not occur elsewhere in Buddhist art, have round faces, sharp noses, flames rising from their heads, powerful bodies and fluid, rounded limbs. Buddha is depicted striding forward.

During this period bronze images of Hindu gods were also cast, to be used as cult objects in royal court rituals performed by Brahmin priests. These Hindu gods wear crowns and royal attire.[7]

Sukhothai also produced a large quantity of glazed ceramics in the Sawankhalok style, which were traded throughout Southeast Asia. There were two forms: monochromatic pottery in brown and white; and celadon and painted wares with dark brown or black designs and a clear glaze.[7]

Ayutthaya period (1350 – 1767)

The surviving art from the Ayutthaya period (1350 – 1767) was primarily executed in stone, characterized by juxtaposed rows of Buddha figures. In the middle period, Sukhothai influence dominated, with large bronze or brick and stucco Buddha images, as well as decorations of gold leaf in free-form designs on a lacquer background. The late period was more elaborate, with Buddha images in royal attire, set on decorative bases. A variety of objects were created in bronze, woodcarving, stucco and sandstone.

-

Buddha head overgrown by fig tree in Wat Mahatat, Ayutthaya historical park

Bangkok (Rattanakosin) period

Thai “Rattanakosin art” (or “Bangkok” style) refers to the style of art of the time of the Chakri Dynasty, founded in Bangkok after the collapse of Ayutthaya in 1767. This period is characterized by the further development of the Ayutthaya style, rather than by innovation.

One important element was the Krom Chang Sip Mu (Organization of the Ten Crafts), a government department originally founded in Ayutthaya, which was responsible for improving the skills of the country's craftsmen. The ten divisions of the Krom Chang Sip Mu give an overview of the craftsmen's arts existing in Thailand during the reign of the Great King Rama V (1853-1910).

- Drawing: Craftsmen, illustrators, pictorial gilders, lacquer craftsmen, painters, muralists and manuscript illustrators.

- Engraving: Woodcarvers, engravers, woodblock cutters, architectural woodcarvers, silversmiths, goldsmiths and jewelers; enameling, inlay and embossing. and architectural woodcarvers.

- Sculpting: Sculptors of plaster and papier mache,decorative fruit and vegetable carvers.

- Modeling: Bronze casters, figure modelers, mask and puppet makers, stucco sculptural and architectural modelers.

- Figuring: Makers of animal and bestiary figures, figure assemblers and lantern-makers.

- Plastering: Plaster craftsmen, stucco workers and sculptors.

- Molding: The making of Buddha images, bronze and metal casting, modeling with clay and bee's wax.

- Lacquering: Lacquer work, gilding, glass mosaic, mother-or-peal inlay work, Buddha images, carvers of wooden panels and pictorial gilding.

- Beating: Metal beaters, manufacturers of monks’ bowls, jewelers, silversmiths.[3]

Thai Rattanakosin art can be classified into two periods: the promotion of classical Siamese traditions under the reigns of Kings Rama I, Rama II, and Rama III; and the period from Rama IV until the present, during which modern Western elements were incorporated into art styles. During the early Bangkok period, numerous works of older sculpture were brought to Bangkok from war torn areas and little new art was created. Later works were ornate, and the simplicity of the earlier period was replaced by lavish ornamentation. During the second period, the images became more human, employing realistic body forms, hairstyles, and pleated toga-style robes. Mural painting and temple ornamentation flourished following the establishment of Bangkok. Beginning in the mid-19th century, paintings show the influence of Western art. [8]

The Emerald Buddha

The Emerald Buddha (Thai: พระแก้วมรกต - Phra Kaew Morakot, or official name พระพุทธมหามณีรัตนปฏิมากร - Phra Phuttha Maha Mani Ratana Patimakorn) is the palladium (Thai: ขวัญเมือง kwan meuang; colloquially มิ่งเมีอง ming meuang) of the Kingdom of Thailand. The figurine of the sitting Buddha is about 45 cm (17.7 inches) tall, made of green jade (rather than emerald), and clothed in gold. It is kept in the Chapel of the Emerald Buddha (Wat Phra Kaew) on the grounds of the Grand Palace in Bangkok. According to legend, the Emerald Buddha was created in India in 43 B.C.E. and was held by various kingdoms until it was brought to Ayutthaya in 1432 after the capture of Angkor Wat. Some art historians believe that the Emerald Buddha belongs to the Chiang Saen Style of the fifteenth century C.E., which would mean it is actually of Lannathai origin. In 1552, it was taken to Luang Prabang, then the capital of the Lao kingdom of Lan Xang, by crown prince of Lan Xang, Setthathirath. [9] In 1564, King Setthathirath moved it to his new capital at Vientiane. In 1779, the Thai General Chao Phraya Chakri put down an insurrection, captured Vientiane and returned the Emerald Buddha to Siam, taking it with him to Thonburi. After he became King Rama I of Thailand, he moved the Emerald Buddha with great ceremony to its current home in Wat Phra Kaew on March 22, 1784.

Contemporary art in Thailand

Thai contemporary art encompasses some of the most diverse and versatile art in Southeast Asia. Thailand is well positioned in the global world of contemporary art with its international and liberal outlook and an almost complete absence of the censorship that restricts artists in many countries of the region. Modern painting in the western sense started late in Thailand, with Silpa Bhirasri (Thai: ศิลป์ พีระศรี, 1892 – 1962), an Italian sculptor who was invited to Thailand to teach Western sculpture at the Fine Arts Department of the Ministry of Palace Affairs in 1923, founding what would become Silpakorn University.

Thai artists are now expressing themselves in a variety of media such as installations, photographs, prints, video art and performance art.

Contemporary Thai art often combines traditional Thai elements with modern techniques. Notable artists in the classical tradition include Chakrapan Posayakrit, Chalermchai Kositpipat and Tawan Dachanee.

Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook, Vasan Sitthiket, Montien Boonma and others have represented Thailand at the Venice Biennale. Vasan Sitthiket is probably the only Thai contemporary artist with work represented in the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City. Chatchai Puipia exhibited at the Asia-Pacific Triennal (1996), the Shanghai Biennale (2002), the Singapore Biennale (2006) and the exhibition Traditions/Tension Southeast Asian Art at the Asia Society in New York. Panya Vijinthanasarn is the Dean of Silpakorn’s Faculty of Painting, Sculpture and Graphic Art.

Younger and up-and-coming artists include Porntaweesak Rimsakul, Yuree Kensaku, Jirapat Tatsanasomboon, Kritsana Chaikitwattana and Thaweesak Srithongdee.

Literature

Literature in Thailand was traditionally heavily influenced by Indian culture. Thailand's national epic is a version of the Ramayana called the Ramakien. A number of versions of the epic were lost in the destruction of Ayutthaya in 1767. Three versions currently exist: one of these was prepared under the supervision (and partly written by) King Rama I. His son, Rama II, rewrote some parts for khon drama. The main differences from the original are an extended role for the monkey god Hanuman and the addition of a happy ending.

The most important poet in Thai literature was Sunthorn Phu (or Sunthon Phu, Thai: สุนทรภู่, 1786–1855), who is best known for his romantic adventure story Phra Aphai Mani and nine travel pieces called Nirats.

Kings Rama V and Rama VI were also writers, mainly of non-fiction works as part of their initiative to combine Western knowledge with traditional Thai culture.

Thai writers of the twentieth century tended to produce light fiction rather than literature, but two notable sociocritical writers came from the Isan region: Pira Sudham (born 1942, Thai พีระ สุธรรม); and Khamsing Srinawk (born 1930, Thai: คำสิงห์ ศรีนอก, also writes under the name Lao Khamhawm), best known for his satirical short stories. A number of expatriate writers have published works in Thailand during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, including Indian author G.Y. Gopinath, the fabulist A.D. Thompson, and non-fiction writer Gary Dale Cearley.

Performing arts

Dance drama

Thai dance (Thai: รำไทย, Template:Lang-lo Ram Thai or ระบำ Rabam) is the main dramatic art form of Thailand. Thai dance drama, like many forms of traditional Asian dance, can be divided into two major categories: classical dance (khon and lakhon) which was once performed only as a religious offering in the royal courts, and folk dance (likay) which evolved as a diversion for common people who did not have access to royal performances. Khon (Thai: โขน) masked dance dramatizes the Ramakien (the Thai version of the Hindu epic, the Ramayana), and embodies the Hindu concept of devaraja (divine kingship). It is highly stylized, with choreography, costumes and masks dictated by tradition. The stories are narrated by a chorus at the side of the stage. Each Khon performance begins with a wai khru rite to pay respect to past masters. Characters wear specific colors associated with their roles. Each character has particular strengths and weaknesses: vanity and valor, flirtation and fidelity, obligations and leadership, jealousy and revenge, cunning and compassion.[10] Lakhon features a wider range of stories than khon, including folk tales and Jataka stories. Dancers are usually female and perform as a group rather than representing individual characters.

Likay is much more varied than lakhon or khon. Stories may be original, and include singing, comedy and ham acting. Costumes may be traditional, modern or a combination of the two. Likay is often performed at village festivals. Thai Likay shares similarities with the Khmer theatre style called Yike. Likay can be traced to Muslim religious performances.

In addition, Thailand has a wide range of regional folk dances performed at festivals and celebrations, and displaying regional influences.

Music

The music of Thailand includes classical and folk music traditions as well as modern string or pop music. Thai musical instruments are varied and reflect ancient foreign influences; they include the klong thap and khim (Persian origin), the jakhe (Indian origin), the klong jin (Chinese origin), and the klong kaek (Indonesian origin).

Thai classical music emerged in its present form within the royal centers of Central Thailand some 800 years ago. Thai classical ensembles, deeply influenced by Khmer and even older practices and repertoires from India, are today uniquely Thai expressions. The three primary classical ensembles, the Piphat, Khruang Sai and Mahori all share a basic instrumentation and theoretical approach. Each employs small hand cymbals (ching) and wooden sticks (krap) to mark the primary beat reference. Several kinds of small drums (klong) are employed in these ensembles to outline the basic rhythmic structure (natab) that is punctuated at the end by the striking of a suspended gong (mong). Classical Thai music is heterophonic - the instruments either play the melody or mark the form. There are no harmony instruments. Instrumentalists improvise idiomatically around the central melody. Rhythmically and metrically, Thai music is steady in tempo, regular in pulse, divisive, in simple duple meter, without swing, with little syncopation (p.3, 39), and with the emphasis on the final beat of a measure or group of pulses and phrase. The Thai scale includes seven tempered notes, instead of a mixture of tones and semitones.[11]

Pop music and other forms of European and American music became popular in Thailand during the twentieth century and influenced the development of several local styles of folk music. The two most popular styles of traditional Thai folk music are luk thung and mor lam; the latter in particular has close affinities with the music of Laos.

Ethnic minorities such as the Lao, Lawa, Hmong, Akha, Khmer, Lisu, Karen and Lahu peoples have retained traditional musical forms.

Nang Yai shadow puppetry

Nang Yai ({{lang-th|หนังใหญ่}, "large shadow puppet") performances originated the beginning of the fifteenth century C.E. at Wat Khanon during the reign of King Chulangkorn and were a popular entertainment during the Ayutthaya period. The performances depict various episodes from the Ramakien. The puppet figures are typically made from perforated cowhide or buffalo hide (more important figures may be made of leopard or bear skin) and weigh approximately 3-4 kg (6-9 lbs). Performances are typically held in the open air, with the puppeteers manipulating the puppets behind a transparent screen, with a fire or bright light behind them casting their shadows on the screen. Puppet shows are accompanied by a musical ensemble and the chants and songs of several narrators.[12]

Nang Yai puppets are still produced and meticulously maintained. The drama group from Wat Khanon performs throughout Thailand. Troupes also exist at Wat Plub in Petchaburi, Wat Sawang Arom in Singburi, Wat Pumarin in Samut SongKram, and Wat Donin in Rayong Province.[13]

Ceramics

The earliest Thai ceramics are those found at Ban Chiang (3,600 B.C.E. – 200 C.E.). Pottery from the later periods was made of buff-colored clay decorated with swirling, fingerprint-like designs. Besides pots, Ban Chiang made many types of ceramics such as vases, jars, animal figurines, ladles, crucibles, spindle whorls and beads. Unglazed, low-fired pottery has been found at other sites throughout Thailand, including Ban Ko in Kanchanaburi province, where archaeologists found earthenware tripod vessels with hollow tapering legs; and Ban Prasat, where fine examples made of black or red clay have been unearthed.[14] The height of ceramic production in Thailand occurred between the fourteenth century and the middle of the sixteenth century, a time of prosperity for both Ayutthaya and Lanna in northern Thailand. King Ramkamhaeng of Sukothai (1237 – 1298) brought potters from China to set up the famous Sukothai kiln. The kilns of Si Satchanalai or Sawankaloke at Goh Noi and Pa Yang are believed by some scholars to predate the Sukothai kiln, perhaps by as much as 200 years.[14] Their domestic wares included coarse, sandy earthenware with cord-marked, stamped or incised decorations; reddish or gray unglazed or partially-glazed stoneware; iron-black Mon ware with rich olive glaze; large dishes with underglaze black decorations; beautiful celadons; covered boxes with grayish, brownish black or gray-black underglaze iron decorations; brown and pearl wares with incised decorations; small vessels with rich honey or dark brown glaze; and cream and white glazed wares.

The Sukothai ceramic industry was almost completely destroyed in 1569 during a Burmese attack. Around 1600, new kilns were built at Singburi to produce coarse utilitarian goods, and Chinese wares were imported in large numbers.

Benjarong

Benjarong (Thai เบญจรงค์; “five colors”) ware is a traditional Tahi porcelain, typically decorated with repetitive geometric or flower-based designs using three to eight colors. Hand-applied, gold masks are laid over the white ceramic, and enamel colors are then applied around the gold and overglazed, creating a tactile effect over the surface of the piece. Each color is applied individually and the piece is kiln fired after each application. The firing process brightens the colors of the finished piece and adds to its beauty. The style of multi-colored enamels on a white porcelain base originated from Ming Dynasty China. Patterns include traditional Thai motifs, such as flora, plant and flame designs, as well as cultural symbols, such as the Garuda (the half-man half-bird mount of the god Vishnu and a symbol of Thai royalty). From the thirteenth to the eighteenth centuries, benjarong porcelain was made exclusively for the use of the royal court; later its use extended to the upper class. Today, benjarong porcelain is appreciated all over the world.[15]

Architecture

Architecture is a significant part of Thailand’s cultural legacy and reflects both the historical importance of architecture to the Thai peoples’ sense of community and religious beliefs, and the challenges posed by Thailand's extreme tropical climate. Influenced by the architectural traditions of many of its neighbors, it has also developed significant regional variation within its vernacular and religious buildings.

Thai Stilt House

A universal aspect of Thailand’s traditional architecture is the elevation of buildings on stilts, most commonly to about six feet above the ground, leaving a space underneath to be used for storage, a workshop, relaxing in the daytime, and sometimes for livestock. The houses were raised as protection from heavy flooding during certain parts of the year, and in more ancient times, protection from predators. Thai building plans are based on superstitious and religious beliefs and affected by considerations such as locally available materials, climate, and agriculture. Thai houses are made from a variety of woods, and from bamboo. Single-family dwellings are expanded when a daughter is married by adding a house on the side to accommodate her new family. A traditional house is built as a cluster of separate rooms arranged around a large central terrace which makes up as much as 40 percent of the floor space. An area in the center of the terrace is often left open to allow the growth of a tree through the structure, providing welcome shade. Furniture is sparse and includes a bed platform, dining table and loose cushions for sitting.

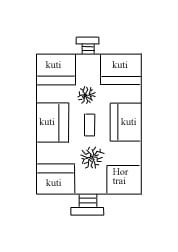

Kuti

A Kuti is a small structure, built on stilts, designed to house a monk. Its proper size is defined in the Sanghathisep, Rule 6, to be “12 by 7 keub” (4.013 by 2.343 meters). This tiny living space is intended to aid the monk's spiritual journey by discouraging the accumulation of material goods. Typically a monastery consists of a number of these buildings grouped together on a shared terrace, either in an inward facing cluster or lined up in a row. Often these structures included a separate building, called a Hor Trai, which is used to store Scriptures.

Religious complexes

A large number of Buddhist temples exist in Thailand. The term Wat is properly used to refer only to a Buddhist site with resident monks, but it is typically used to refer to any place of worship other than the Islamic mosques found in southern Thailand.

A typical Wat Thai has two enclosing walls that divide it from the secular world. The monks' or nuns' quarters or dormitories are situated between the outer and inner walls. This area may also contain a bell tower or hor rakang. In larger temples, the inner walls may be lined with Buddha images and serve as cloisters or galleries for meditation. This part of the temple is called buddhavasa or phutthawat (for the Buddha).

Inside the inner walls is the bot or ubosoth (ordination hall), surrounded by eight stone tablets and set on consecrated ground. This is the most sacred part of the temple and only monks can enter it. The bot contains a Buddha image, but it is the viharn (assembly hall) that contains the principal Buddha images. Also, in the inner courtyard are the bell-shaped chedi (relic chambers), which contain the relics of pious or distinguished people. Salas (rest pavilions) can be found all around the temple; the largest of these area is the sala kan parian (study hall), used for saying afternoon prayers.

Textiles

Every region of Thailand has its signature textiles: loose weave cotton in the north; batik in the south; and royal designs in the central plains. The region of Isaan has a particularly diverse fabric heritage. Thailand is famous for its handwoven silks, made from the yellow cocoons of the bombyx mori silk worm. The textured outer part of the Thai cocoon is carefully separated from the inner smoother, lustrous silk. Each cocoon yields 900 meters of silk yarn, so fine that several strands must be twisted together before being hand-woven into very fine silk.

The southern part of Northeastern Thailand, or Isaan, is home to Cambodian speaking peoples surrounding Surin and Lao peoples in the Buriram area, whose textiles reflect their historical and ethnic backgrounds. Cotton cannot be grown because of the dry climate, so many families raise silkworms. Weaving is done during the time between rice plantings and harvests. A tie-dyeing technique called mudmee (ikat) is used to color the skeins of silk before weaving. The individual dyed threads are then arranged on the loom, one by one, so that they form an intricate pattern when woven. The woven fabric appears to shimmer.[16] Mee hol is an extremely delicate mudmee design dyed with three natural dyes that overlap to create six shades. A sophisticated double mudmee cloth called am prom is a fine red silk with minute dots of white resulting from the resist tying of both warp and weft yarns. Two techniques, phaa khit (usually woven from cotton) and prae wa (woven from silk) use a continuous supplementary weft, resulting in a raised, almost embroidered look. Complex multi-shaft bird’s-eye or diamond twill designs are woven into traditional shoulder cloths called swai soa. Silk brocades are also produced.[17] Though there has been a steady decline in the demand for handwoven silks since the 1960s, the social structure in rural villages enables skilled weaving to continue. Isaan women still weave fine silk fabrics to be presented as offerings, or as ritual textiles to be worn to the temple or for festive ceremonies such as weddings. Renewed appreciation of traditional arts has motivated the revival of techniques that had been unused for almost a century, and many fabrics are woven for tourists and for export.[17] In the absence of a detailed written history of the area, textiles, along with other cultural traditions, serve as valuable archeological evidence of ethnic migrations.

Folk art

Thailand has a rich variety of folk arts. Traditional crafts that once produced objects for everyday use have survived in rural villages and are now being revived to produce items of beauty for sale and export. Often entire villages are involved in the manufacture of a single item, such as painted parasols, silver jewelry, pewter ware, teak carvings, or wooden bowls, with each family taking responsibility for one aspect of production.[18] The art of making lacquer originally came from China and evolved unique Thai designs and techniques. Lacquerware is produced in the northern province of Chiang Mai through a painstaking process that involves imbedding colored paint and gold into engraved patterns. Lacquer is used to decorate everything from figurines, toys, bowls, trays and boxes to architectural features such as window frames.[19] Over the centuries, gifted woodcarvers have created religious figures and elaborate decorations for Buddhist temples all over Thailand. Intricately carved wooden furniture, bowls, lamp bases and other decorative items are produced for the domestic market and for export.

Silverware has been a prominent craft in northern Thailand for more than 1000 years. Silversmiths use repoussé techniques to adorn silver bowls and boxes with traditional Thai motifs. Nielloware (kruang tom) reached Thailand during the Ayutthaya period and became prominent in southern Thailand. Niello artisans fashion every conceivable object from sheets of finely engraved silver, sometimes covered with old.[20]

Other important crafts include the manufacture of dolls, parasols, baskets from wood and bamboo, toys, reed mats, and items with mother-of-pearl inlay.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Thailand History Thailandsworld.com Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 History Thai Community and Cultural Arts Center. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Manual Arts in Thai Tradition Asia-art.net. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ↑ Prehistoric Art In Thailand. thailandsworld.com. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ↑ Srivijaya Art Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ↑ Mon Dvaravati Art Thailand Thailandsworld.com. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Thai Sukhothai Style Art Thailandsworld.com. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ↑ Thaliandsworld.com, Thai Rattanakosin Style Art Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ↑ Setthathirath was of Lao, Thai and Lanna heritage, so was a Prince of Ayuttaya & Chiang Mai as well as the crown prince of Luang Prabang. Thai history records that Setthathirath removed the image without authority when the government of Chiang Mai fell into strife.

- ↑ Philip Cornwell-Smith, Khon tatnews.org. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ↑ David Morton. (1976). The Traditional Music of Thailand. (Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520018761), 3–41

- ↑ Nang Yai Shadow Puppets Retrieved January 27, 2009.

- ↑ สำนักงานคณะกรรมการวัฒนธรรมแห่งชาติ Retrieved January 27, 2009.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Art of Thai Ceramics Asia-art.net. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ↑ History of Benjarong Porcelain thaibenjarong.com. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ↑ Patricia Cheesman, Traditional Textiles of Lower I-san tatnews.org. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Morrison Polkinghorne, Handwoven Heritage tatnews.org. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ↑ Introduction Thai Folk Arts and Crafts. Seameo.org. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- ↑ Lacquerware Thai Folk Arts and Crafts. Seameo.org. Retrieved January 26, 2009

- ↑ Nielloware Thai Folk Arts and Crafts. Seameo.org. Retrieved January 26, 2009

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Döhring, Karl. Buddhist Temples of Thailand: An Architectonic Introduction. White Lotus. 2000. ISBN 9747534401

- Higham, Charles, and Rachanie Thosarat. Prehistoric Thailand: from early settlement to Sukhothai. Bangkok: River Books. 1998. ISBN 9748225305

- Morton, David. 1976. The Traditional Music of Thailand. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520018761

- Ruethai Chaichongrak. Thai House: History And Evolution. Weatherhill. 2002. ISBN 0834805200

- Time-Life Books. Southeast Asia: a past regained. (Lost civilizations.) Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books. 1995. ISBN 9780809491124

- Van Beek, Steve, and Luca Invernizzi. The Arts of Thailand. [S.l.]: Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. 1999. ISBN 9625932623

- Woodward, Hiram W. The art and architecture of Thailand: from prehistoric times through the thirteenth century. Leiden: Brill. 2003. ISBN 9004121374

External links

All links retrieved January 24, 2020.

- Wat Thai: Dhammathai

- Thai Temples

- Thai Stories

- Thai Architecture

- Rama IX Art Museum Virtual museum of Thai contemporary artists. Listings of museums, galleries, exhibitions and venues. Contains lots of information on Thai artists and art activities.

|

||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Thai_art history

- Sukhothai_Kingdom history

- Ayutthaya history

- Amphoe_Sawankhalok history

- Ayutthaya history

- Thai_contemporary_art history

- Culture_of_Thailand history

- Dance_of_Thailand history

- Nang_yai history

- Thai_temple_art_and_architecture history

- Emerald_Buddha history

- Wat_Pho history

- Benjarong history

- Wat_Benchamabophit history

- Wat_Phra_Kaew history

- Suan_Pakkad_Palace history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 23:54:33 | 57 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Thai_art | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF