Saturn

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia - For other uses, please see Saturn (disambiguation).

| Saturn | |

|---|---|

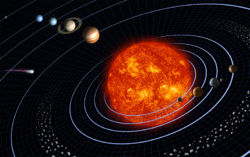

Composite true-color image of Saturn by spacecraft Cassini in October of 2004. | |

| Symbol | |

| Name origin | Roman god of harvest |

| Orbital characteristics | |

| Primary | Sun |

| Order from primary | 7 |

| Perihelion | 1,352,550,000 km[1] |

| Aphelion | 1,514,500,000 km[1] |

| Semi-major axis | 1,433,530,000 km[1][2] |

| Titius-Bode prediction | 10.0 AU |

| Circumference | 59.879 AU |

| Orbital eccentricity | 0.0565[1] |

| Sidereal year | 10,759.22 da (29.4 a)[1] |

| Synodic year | 378.09 da[1] |

| Avg. orbital speed | 10.183 km/s |

| Inclination | 2.485°[1] to the ecliptic |

| Rotational characteristics | |

| Sidereal day | 10.656 h[1] |

| Solar day | 10.656 h[1] |

| Rotational speed | 9.8663 m/s[3] |

| Axial tilt | 26.73°[1] |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Mass | 5.6846 * 1026 kg[1] |

| Density | 687.3 kg/m³[1] |

| Mean radius | 58,232 km[1] |

| Equatorial radius | 60,268 km[1] |

| Polar radius | 54,364 km[1] |

| Surface gravity | 8.96 m/s²[1] |

| Escape speed | 35.49 km/s[1] |

| Surface area | 42,612,000,000 km²[3] |

| Mean temperature | 134 K |

| Number of moons | 60 |

| Composition | hydrogen 96.3%, helium 3.25%, methane 4500 ppm, ammonia 125 pm, hydrogen deuteride 110 ppm, ethane 1.5 ppm, plus aerosols of ammonia ice, water ice, and ammonia hydrosulfide[1] |

| Color | light yellow |

| Albedo | 0.47[1] |

| Magnetosphere | |

| Magnetic flux density | 0.210 G[1] |

| Magnetic dipole moment at present | 4.6 * 1025 N-m/T[4][5] |

| Magnetic dipole moment at creation | 1.34 * 1026 N-m/T[5] |

| Decay time | 5300 a[5] |

| Half life | 3700 a[3] |

Contents

Ancient knowledge and naming[edit]

Saturn has been known to post-diluvian man since the beginnings of recorded history.[6] The Hindus called Saturn Sani, one of nine objects called the Navagraha that constituted a celestial council. (The other eight members of this council were the Sun, the Moon, the modern planets Mars, Venus, Mercury, and Jupiter, and the ascending and descending nodes of the Moon's orbit, which the Hindus named Rahu and Ketu.) The Hindus feared Sani above all other objects, believing that he could burn any object instantly by merely glancing at it.[7]

The ancient Greeks regarded this object, the furthest moving object that they knew, as the father of all the classical gods. They named him Kronos or Cronus,[6] a word closely akin to chronos, which means time. That Jupiter is far more prominent in the sky was a sign to the Greeks that Zeus, the most prominent son of Kronos, had deposed him, even as Kronos had deposed his own father, Ouranos (Uranus).

The Romans named this deity Saturnus and regarded him not merely as the father of the gods but also as the patron of agriculture and the harvest. His symbol, a stylized rendering of a sickle, reflects that association. The name Saturn also appears in the name of Saturday, the English name for the seventh day of the week.[6]

Orbital characteristics[edit]

Saturn's orbit is about 3.4 times as eccentric as Earth's orbit. Saturn keeps an average orbital distance of 1,433,530,000 km from the sun, a distance close to that predicted by the Titius-Bode Law.[1] Saturn's orbit is slightly inclined to the ecliptic, with the result that the Earth passes from one side to the other of Saturn's ring plane every so often.[6] Saturn's sidereal period is about 29.4 Earth years. Its synodic period is 378.09 days.

Physical characteristics[edit]

Saturn's volumetric mean radius is 58,232 km. Remarkably, Saturn is less dense than water. Its chief constituent is molecular hydrogen, followed by helium, methane, ammonia, hydrogen deuteride, and ethane. Aerosols of ammonia ice, water ice, and ammonia hydrosulfide complete Saturn's composition.

Saturn has high winds, which blow easterly at 500 m/s at the equator.[8]

Magnetosphere[edit]

Saturn has a magnetic dipole moment of 4.6 * 1025 N-m/T, less than one-thirtieth of that of Jupiter. Remarkably, the magnetic axis deviates only slightly from the rotational axis. The magnetophere extends slightly beyond the orbit of Titan, and Titan's upper atmosphere contributes plasma particles to the Saturnine magnetosphere.[4]

Ring system[edit]

Saturn’s ring system is the brightest in all the solar system, with an albedo varying from 0.2 to 0.6, often brighter than the planet itself.[6]

The rings have radii varying from 60,268 km to 483,000 km. Saturn's rings divide into seven portions, designated D, C, B, A, F, G, and E from inner to outer. A wide gap called the Cassini Division separates the B and A rings, and the A rings themselves have two gaps, called the Encke and Keeler gaps.[9]

The two Voyager spacecraft sent back cinematic images that showed that the rings were spoked, and that the spokes persist, especially in the B ring system.[6][8] Current theories suggest that the spokes result from magnetic interaction, because the rings all lie well within Saturn's magnetosphere. Furthermore, the F ring appears to be braided, a phenomenon that remains unexplained today.[6]

Many of the innermost moons of Saturn orbit close to the rings, especially the F and E rings, and serve to regularize their structure, a phenomenon called "shepherding."[8]

As of October 8, 2009, scientists have discovered another massive ring system that could not previously be seen.[10]

Problems for uniformitarian theories[edit]

The origin of Saturn's rings remains a mystery,[6][8] and a troublesome one. The rings are not stable and hence could not have persisted for the whole of the assumed deep time age of the solar system.[6] Uniformitarians admit that Saturn's rings could not be older than about 100 million years.[6] They therefore propose that Saturn's rings formed from the disintegration of one or more moons, perhaps following a collision with a comet.[6][8] However, Wing-Huan Ip at the Max Planck Institute calculated that a comet-moon collision would not be sufficiently likely to occur in less time than 30 billion years. This is more than twice the age of the universe calculated from the Hubble Constant.[11]

Observation and Exploration[edit]

Galileo Galilei was the first astronomer to observe Saturn with a telescope. But he did not realize that he was looking at a ringed planet. Only in 1659 did Christiaan Huygens understand that Saturn was ringed. For three centuries more, Saturn's ring system was the only such system known, until in 1977 NASA astronomers inferred the ring system of Uranus from a stellar occultation experiment.

Telescopic observation of Saturn has been ongoing since the earliest observations by Huygens and Giovanni Domenico Cassini. The Hubble Space Telescope and many Earth-based telescopes have taken many images of a quality comparable to that of images sent back from spacecraft.

The first spacecraft to visit Saturn was Pioneer 11 in 1979, followed by Voyager 1 (1980) and Voyager 2 (1981).[6] The spacecraft of the joint NASA/ESA Cassini-Huygens Mission arrived in the Saturnine system on July 1, 2004.[6] The Huygens spacecraft landed on Saturn's largest moon, Titan, and transmitted images and data all during its descent and for three hours after landing. The Cassini spacecraft continues to orbit Saturn and make frequent rendezvous with its most prominent moons to this day (May 19, 2008). Its mission was originally scheduled to run for four years, ending in July 2008, but NASA has announced a two-year extension with multiple rendezvous with Titan and additional rendezvous with Enceladus, Rhea, Dione, and Helene. Mission planners also suggest that after two years, Cassini might still have enough fuel for another two-year extension, and speak hopefully of specific future missions to Titan and Enceladus.[12]

Gallery[edit]

Satellites[edit]

Saturn has at least sixty confirmed satellites and three unconfirmed satellites. Of the sixty known satellites, five are "ring shepherds."[13] Two of the satellites, Epimetheus and Janus, actually exchange orbits regularly. Two of the largest moons, Tethys and Dione, each have two moons that occupy the stable libration or "Trojan" points in their respective orbits. Most of Saturn's moons lie beyond the orbit of Iapetus, the outermost of the large spheroidal moons.

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 Williams, David R. "Saturn Fact Sheet." National Space Science Data Center, NASA, November 23, 2007. Accessed May 19, 2008.

- ↑ "Space Topics: Saturn." The Planetary Society. Accessed May 19, 2008.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Calculated

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Russell, C. T., and Luhmann, J. G. "Saturn: Magnetic Field and Magnetosphere." Encyclopedia of Planetary Sciences, J. H. Shirley and R. W. Fainbridge, eds. New York: Chapman and Hall, 1997, pp. 718-719. Accessed May 19, 2008.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Humphreys, D. R. "The Creation of Planetary Magnetic Fields." Creation Research Society Quarterly 21(3), December 1984. Accessed April 29, 2008.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 Arnett, Bill. "Entry for Saturn." The

Nine8 Planets, May 11, 2005. Accessed May 19, 2008. - ↑ "Entry for Sani." Windows to the Universe, University Corporation for Atmospheric Research, University of Michigan, July 19, 2001. Accessed May 19, 2008.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Hamilton, Calvin J. "Entry for Saturn." Views of the Solar System, 1997-2005. Accessed May 19, 2008.

- ↑ Williams, David R. "Saturnian Rings Fact Sheet." NASA, September 18, 2006. Accessed May 19, 2008.

- ↑ http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/science/space/article6864286.ece

- ↑ Harris, David M. "How Old are Saturn's Rings?" Creation, 12(4):40–41. September 1990. Accessed May 18, 2008.

- ↑ Brown, Dwayne, and Martinez, Carolina. "NASA Extends Cassini's Grand Tour of Saturn." NASA, April 15, 2008. Accessed May 16, 2008.

- ↑ The three unconfirmed satellites, if confirmed, would also be ring shepherds. In addition, the A ring has a large collection of "moonlets" that shepherd the other smaller particles.

Related Links[edit]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/19/2023 01:16:59 | 313 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Saturn | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF