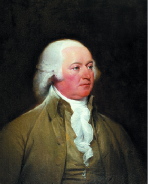

John Adams

From Nwe

From Nwe

|

|

|

| Term of office | March 4, 1797 – March 4, 1801 |

| Preceded by | George Washington |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Jefferson |

| Date of birth | October 30, 1735 |

| Place of birth | Braintree, Massachusetts |

| Date of death | July 4, 1826 |

| Place of death | Quincy, Massachusetts |

| Spouse | Abigail Adams |

| Political party | Federalist |

John Adams (October 30, 1735—July 4, 1826) was a revolutionary patriot, Massachusetts delegate to the First and Second Continental Congress, signer of the Declaration of Independence, minister to France who helped negotiate the Treaty of Paris ending the Revolutionary War, first U.S. foreign minister to Great Britain, and first vice president and second president of the United States. Among the Founding Fathers, Adams played a leading role in articulating arguments for independence and defining republicanism as the core American governing principle.

Adams was the author of the Massachusetts constitution, the new nation's first state charter. Although serving in France during the framing of the federal Constitution in 1787, Adams was an unseen presence whose political treatise Thoughts on Government profoundly influenced the deliberations in Philadelphia.

As President, Adams was frustrated by battles inside his own Federalist party against a faction led by Alexander Hamilton, but he broke with them and averted a major war with France in 1798. A bitter political enemy of Thomas Jefferson, who succeeded him after one term in office, Adams signed the Alien and Sedition Acts, soon repealed, which criminalized certain political speech. Adams ultimately reconciled with Jefferson and the two statesmen carried on a generation-long correspondence from their respective retirements in Massachusetts and Virginia. Adams and Jefferson died at their homes, miraculously, on July 4, 1826, the fiftieth anniversary of the adoption of Declaration of Independence.

Adams was arguably the most religiously devout of the Founders. Although not a doctrinaire Christian—he once wrote to Jefferson that "the Ten Commandments and the Sermon on the Mount contain my religion"—Adams believed that the success of the American experiment in self government ultimately depended upon the virtue of the people. "We have no government armed in power capable of contending with human passions unbridled by morality and religion," Adams said in an address to the military in 1798. "Our Constitution was made only for a religious and moral people. It is totally inadequate for the governance on any other."[1]

A fourth-generation American whose Puritan ancestors arrived in Massachusetts in 1636, Adams was the father of John Quincy Adams, the sixth president of the United States; grandfather of Charles Francis Adams, a leading diplomat who played a critical role in persuading Great Britain to remain neutral during the American Civil War; and great-grandfather of Henry Adams, author of The Education of Henry Adams and a noted historian of early American history. Writing to his wife with an eye to his posterity he famously observed, "I must study politics and war, that our sons may have liberty to study mathematics and philosophy. Our sons ought to study mathematics and philosophy, geography, natural history and naval architecture, navigation, commerce and agriculture in order to give their children a right to study painting, poetry, music, architecture, statuary, tapestry and porcelain."[2]

Early life

John Adams was born the eldest of three brothers on October 30, 1735 , in Braintree, Massachusetts, though in an area which became part of Quincy, Massachusetts in 1792. His birthplace is now part of Adams National Historical Park. His father, a farmer, also named John, was a fourth-generation descendant of Henry Adams, who immigrated from Barton St David, Somerset, England, to Massachusetts Bay Colony in about 1636. His mother was Susanna Boylston Adams.

Young Adams graduated from Harvard College in 1755 and, for a time, taught school in Worcester and studied law in the office of James Putnam. In 1761, he was admitted to the bar. From an early age, he developed the habit of writing descriptions of events and impressions of men. The earliest known example of these is his report of the 1761 argument of James Otis in the superior court of Massachusetts as to the legality of Writs of Assistance. Otis’s argument inspired Adams with zeal for the cause of the American colonies. Years later, when he was older, Adams undertook to write out, at length, his recollections of this scene.

In 1764, Adams married Miss Abigail Smith, the daughter of a Congregational minister, at Weymouth, Massachusetts. Their children were Abigail Amelia; future president John Quincy; Susanna Boylston; Charles; Thomas Boylston; and Elizabeth who was stillborn.

Adams lacked the genius for popular leadership shown by his second cousin, Samuel Adams; instead, his influence emerged through his work as a constitutional lawyer and his intense analysis of historical examples, together with his thorough knowledge of the law and his dedication to the principles of Republicanism. Adams is credited with drafting the Massachusetts Constitution. Impetuous, intense and often vehement, Adams often found his inborn contentiousness to be a handicap in his political career. These qualities were particularly manifested at a later period, for example, during his term as president when he lost control of his own cabinet and his Federalist party.

Politics

Adams first rose to influence as an opponent of the Stamp Act of 1765. In that year, he drafted the instructions which were sent by the inhabitants of Braintree to its representatives in the Massachusetts legislature, and which served as a model for other towns to draw up instructions to their representatives. In August 1765, he anonymously contributed four notable articles to the Boston Gazette, in which he argued that the opposition of the colonies to the Stamp Act was a part of the never-ending struggle between individualism and corporate authority. In December 1765, he delivered a speech before the governor and council in which he pronounced the Stamp Act invalid on the ground that Massachusetts, being without representation in Parliament, had not assented to it.

In 1768, Adams moved to Boston. After the Boston Massacre in 1770, several British soldiers were arrested and charged with the murder of four colonists, and Adams joined Josiah Quincy II in defending them. The trial resulted in an acquittal of the officer who commanded the detachment and most of the soldiers; but two soldiers were found guilty of manslaughter. These men claimed benefit of clergy and were branded in the hand and released. Adams' conduct in taking the unpopular side in this case resulted in his subsequent election to the Massachusetts House of Representatives by a vote of 418 to 118 in 1770. At about this same time, he joined the Sons of Liberty.

Continental Congress

Adams was a member of the Continental Congress from 1774 to 1778. In 1775, he was appointed the chief judge of the Massachusetts Superior Court. In June 1775, with a view to promoting the union of the colonies, he nominated George Washington as commander-in-chief of the army. His influence in Congress was great, and almost from the beginning, he sought permanent separation from Great Britain. On October 5, 1775, Congress created the first of a series of committees to study naval matters. From that time onward, Adams championed the establishment and strengthening of an American Navy and is often referred to as the father of the United States Navy.

On May 15, 1776 the Continental Congress, in response to escalating hostilities which had climaxed a year prior at Lexington and Concord, urged that the states begin constructing their own constitutions.

Today, the Declaration of Independence is remembered as the great revolutionary act, but Adams and most of his contemporaries saw the Declaration as a mere formality. The resolution to draft independent constitutions was, as Adams put it, "independence itself."

Over the next decade Americans from every state gathered and deliberated on new governing documents. As radical as it was to actually write constitutions (prior convention suggested that a society's guiding principles should remain uncodified), what was equally radical was the nature of American political thought as the summer of 1776 dawned.

Thoughts on Government

At that time, Adams penned his Thoughts on Government (1776), the most influential of all political pamphlets written during the constitution-writing period. Thoughts on Government stood as the clearest articulation of the classical theory of mixed government and, in particular, how it related to the emerging American situation. Adams contended, with remarkable force and persuasion, the necessary existence of social estates in any political society, and the need to precisely mirror those social estates in the political structures of the society. For centuries, dating back to Aristotle, a mixed regime balancing monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy, or the monarch, nobles, and people was required to preserve order and liberty.

Adams, viewing the world through a thoroughly classical lens, thought all American state constitutions needed to exhibit a wise balance much like the ancient English Constitution had for so long. What was problematic with the English version, and indeed what plagued the entire ancient regime, was its understanding of the aristocracy. Adams and his fellow American political thinkers resented little as much as a hereditary nobility distinguished by wealth and land. Such people lacked the necessary virtue to balance the people in the legislature, Adams thought, and were prone to corruption.

Indeed, it was corrupt and nefarious elites, in the English Parliament and stationed in America, who were blamed most for the assault on liberty perceived by so many Americans and responsible for the move towards independence. Adams, unlike some Americans, was not keen on eliminating all vestiges of aristocracy. Thoughts on Government defended bicameralism, but in place of a landed aristocracy based on birth, a natural aristocracy based on merit and talent would suffice. A distinguished group of independent, virtuous gentlemen, as Adams put it, could adequately balance the passions of the people represented in the lower house of the legislature. Thoughts on Government's new rendition of the classical theory of mixed government was enormously influential and was referenced as an authority in every state-constitution writing hall.

Massachusetts' eventual constitution, ratified in 1780 and written largely by Adams himself, structured its government most closely on this view of politics and society. As the decade unfolded, and political debate reached a fiery pitch across the newly independent states, the ideas expressed so forcefully by Adams, whether agreed with or despised, could be found at the center of most pressing discussions about politics and society in newspapers, pamphlets, and convention halls.

Declaration of Independence

On June 7, 1776, Adams seconded the resolution introduced by Richard Henry Lee that "these colonies are, and of a right ought to be, free and independent states," acting as champion of these resolutions before the Congress until their adoption on July 2, 1776.

He was appointed on a committee with Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Robert R. Livingston and Roger Sherman, to draft a Declaration of Independence. Although that document was largely drafted by Jefferson, John Adams occupied the foremost place in the debate on its adoption. Many years later, Jefferson hailed Adams as, "The Colossus of that Congress—the great pillar of support to the Declaration of Independence, and its ablest advocate and champion on the floor of the House." In 1777, he resigned his seat on the Massachusetts Superior Court to serve as the head of the Board of War and Ordinance, as well as many other important committees.

Diplomat in Europe

Before this work had been completed, he was chosen as minister plenipotentiary for negotiating a treaty of peace and a treaty of commerce with Great Britain, and again he was sent to Europe in September 1779. The French government, however, did not approve of Adams’ appointment and subsequently, on Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes’ insistence, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, John Jay and Henry Laurens were appointed to cooperate with Adams. Since Jefferson did not leave the United States for the task and Laurens played a minor role, Jay, Adams and Franklin played the major part in the negotiations. Overruling Franklin, Jay and Adams decided not to consult with France; instead, they dealt directly with the British commissioners.

Throughout the negotiations, Adams was especially determined that the right of the United States to the fisheries along the British-American coast should be recognized. Eventually, the American negotiators were able to secure a favorable treaty, which was signed on November 30, 1782. Before these negotiations began, Adams had spent some time in the Netherlands. In July 1780, he had been authorized to execute the duties previously assigned to Laurens. With the aid of the Dutch patriot leader Joan van der Capellen tot den Pol, Adams secured the recognition of the United States as an independent government at The Hague on April 19, 1782. The Netherlands was the first European country to grant diplomatic recognition to the US, who appointed Adams as the first ambassador. During this trip, he also negotiated a loan and, in October 1782, a treaty of amity and commerce, the first of such treaties between the United States and foreign powers after that of February 1778 with France. Moreover, the house that Adams purchased during this stay in the Netherlands became the first American embassy on foreign soil anywhere in the world.

In 1785, John Adams was appointed the first American minister to the court of St. James. When he was presented to his former sovereign, George III, the King intimated that he was aware of Adams' lack of confidence in the French government. Adams admitted this, stating: "I must avow to your Majesty that I have no attachment but to my own country."

A Defence of the Constitution (1787)

While in London, Adams published a work entitled A Defence of the Constitution of Government of the United States, in which he repudiated the views of Turgot and other European writers as to the viciousness of the framework of state governments. In this work, he made the controversial statement that "the rich, the well-born and the able" should be set apart from other men in a senate. Such comments were common among Federalists and other leading Founders in 1787, but the basic understanding of politics animating such conclusions were not. Adams, some have maintained, had become intellectually irrelevant by the time the Federal Constitution was ratified. By then, American politic thought, transformed by more than a decade of vigorous and searching debate as well as shaping experiential pressures, had abandoned the classical conception of politics which understood government as a mirror of social estates. As James Madison's writings above all show, Americans new conception of popular sovereignty, now saw the people-at-large as the sole possessors of power in the realm. All agents of the government enjoyed mere portions of the people's power, and only for a limited period of time. Sovereignty was divisible and limited, in other words. Adams had completely missed this concept. In A Defence of the Constitution of Government of the United States, Adams revealed his continued attachment to the older version of politics and failed to comprehend the changes in political thought which had culminated in the document he was defending.

One of the more intriguing ironies of the American Revolutionary period, was Adams inability to fully grasp the changes surrounding him. As his contemporaries shaped a new and radical conception of politics, Adams clung, unknowingly, to a collection of categories and assumptions which were fast becoming archaic.

Vice Presidency

While Washington was the unanimous choice for president, Adams came in second in the electoral college and became Vice President in the presidential election of 1789. He played a minor role in the politics of the 1790s and was reelected in 1792. The reason Adams played, involuntarily, a smaller role in the government, and indeed in the decisions of the Executive, was for precisely and only the reason that the Senate forbade the Vice President from taking part in their debates and Washington never asked Adams' for input on policy and legal issues. The view was that the Vice President was to be the tie breaker in the Senate and the step-in for any untimely death or incapacitation of the President. Taking the backseat was something that Adams, the firebrand of the Revolution, was not accustomed to taking.

As president of the Senate, Adams cast twenty-nine tie-breaking votes, a record that only John C. Calhoun came close to tying, with twenty eight. His votes protected the president's sole authority over the removal of appointees and influenced the location of the national capital. On at least one occasion, he persuaded senators to vote against legislation that he opposed, and he frequently lectured the Senate on procedural and policy matters. Adams' political views and his active role in the Senate made him a natural target for critics of the Washington administration. Toward the end of his first term, as a result of a threatened resolution that would have silenced him except for procedural and policy matters, he began to exercise more restraint in the hope of realizing the goal shared by many of his successors: election in his own right as president of the United States. When the two political parties formed, he joined the Federalist Party and was its nominee for president in 1796, against Thomas Jefferson, the leader of the opposition Republican Party.

Presidency: 1797-1801

Policies

In 1796, after Washington refused to seek another term, Adams was elected president, defeating Thomas Jefferson, who became Vice President. He followed Washington's lead in making the presidency the exemplar of republican values and stressing civic virtue. He was never implicated in any scandal.

Adams' four years as president were marked by intense disputes over foreign policy. Great Britain and France were at war; Adams and the Federalists favored Britain, while Jefferson and the Republicans favored France. An undeclared naval war between the U.S. and France, called the Quasi-War, broke out in 1798. The humiliation of the XYZ Affair led to serious threat of full-scale war with France. Adams and the moderate Federalists were able to avoid a war through various measures, some of which proved unpopular. The Federalists built up the army under George Washington and Alexander Hamilton, built warships, such as the USS Constitution, and raised taxes. They cracked down on political immigrants and domestic opponents with the Alien and Sedition Acts, which were signed by Adams in 1798. Those Acts, and the high-profile prosecution of a number of newspaper editors and one Congressman by the Federalists, became highly controversial. Some historians have noted that the Alien and Sedition Acts were relatively rarely enforced, as only ten convictions under the Sedition Act have been identified and as Adams never signed a deportation order, and that the furor over the Alien and Sedition Acts was mainly stirred up by the Republicans. However, other historians emphasize that the Acts were highly controversial from the outset, resulted in many aliens leaving the country voluntarily, and created an atmosphere where opposing the Federalists, even on the floor of Congress, could and did result in prosecution. Regardless of the perspective taken, it is generally acknowledged that the election of 1800 became a bitter and volatile battle, with each side expressing extraordinary fear of the other party and its policies.

The deep split in the Federalist party came on the army issue. Adams was forced to name Washington as commander of the new army, and Washington demanded that Hamilton be given the number two position. Adams reluctantly gave in. Indeed, Major General Hamilton virtually took control of the War department. The rift between Adams and the High federalists grew wider. The High Federalists refused to consult Adams over the key legislation of 1798; they changed the defense measures which he had called for; they demanded Hamilton control the army; refused to recognize the necessity giving key Republicans like Aaron Burr) senior positions in the army, thereby splitting the Republicans. By relying too heavily on a standing army the High Federalists raised popular alarms and played into the hands of the Republicans. They also alienated Adams and his large personal following. They shortsightedly viewed the Federalist party as their own tool and ignored the need to pull together the entire nation in the face of war with France.

For long stretches, Adams withdrew to his home in Massachusetts. In February 1799, Adams stunned the country by sending diplomat William Vans Murray on a peace mission to France. Napoleon was now in power in Paris; realizing the animosity of the United States was doing no good, he signaled his readiness for friendly relations. The Treaty of Alliance of 1778 was superseded and the United States could now be free of foreign entanglements, as Washington advised in his own Farewell Letter. Adams avoided war, but deeply split his own party in the process. He brought in John Marshall as Secretary of State and demobilized the emergency army.

Reelection campaign 1800

The death of Washington, in 1799, weakened the Federalists, as they lost the one man who symbolized and united the party. Adams lost what little support that he had from high ranking Federalists when he granted pardons to participants in Fries's Rebellion. In the presidential election of 1800, Adams ran and lost the electoral vote narrowly. The six states where popular votes occurred, they were votes for electors, though Jefferson's and Burr's electors won those votes handily, with over 61 percent of the popular vote. Among the causes of his defeat was distrust of him in his own party, a scathing pamphlet, Letter from Alexander Hamilton, Concerning the Public Conduct and Character of John Adams, Esq. President of the United States, a smear campaign full of libel, written by Alexander Hamilton that further split his party support, the popular disapproval of the Alien and Sedition Acts, the popularity of his opponent, Thomas Jefferson, and the effective politicking of Aaron Burr and others in New York, where the legislature statewide shifted from Federalist to Republican on the basis of a few wards in New York City controlled by Burr's Tammany Hall machine.

Midnight judges

As his term was expiring, he appointed a series of judges, who were nicknamed "Midnight Judges" because most of them were formally appointed less than 30 days before John Adams' presidential term expired. Most of the judges were eventually unseated when the Jeffersonians repealed their offices, but their unseating was a point of controversy between Federalists and Jeffersonians because they were repealed on a technicality. But John Marshall remained, and his long tenure as Chief Justice of the United States represents the most lasting influence of the Federalists, as he refashioned the Constitution into a nationalizing force and established the Judicial Branch as the equal of the Executive and Legislative.

Major presidential acts

- Established the United States Department of the Navy and created the Secretary of the Navy Cabinet post in 1798

- Avoided war with France through diplomacy

- Signed Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798

- Signed Judiciary Act of 1801

Speeches

Inaugural Addresses

- Inaugural Addresses (4 March 1797)

State of the Union Address

- First State of the Union Address (22 November 1797)

- Second State of the Union Address, (8 December 1798)

- Third State of the Union Address, (3 December 1799)

- Fourth State of the Union Address, (22 November 1800)

Administration and Cabinet

| OFFICE | NAME | TERM |

| President | John Adams | 1797–1801 |

| Vice President | Thomas Jefferson | 1797–1801 |

| Secretary of State | Timothy Pickering | 1797–1800 |

| John Marshall | 1800–1801 | |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Oliver Wolcott, Jr. | 1797–1800 |

| Samuel Dexter | 1800–1801 | |

| Secretary of War | James McHenry | 1797–1800 |

| Samuel Dexter | 1800–1801 | |

| Attorney General | Charles Lee | 1797–1801 |

| Postmaster General | Joseph Habersham | 1797–1801 |

| Secretary of the Navy | Benjamin Stoddert | 1798–1801 |

Supreme Court appointments

Adams appointed the following Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- Bushrod Washington – 1799

- Alfred Moore – 1800

- John Marshall (Chief Justice) – 1801

Post Presidency

Following his 1800 defeat, Adams retired into private life. He went back to farming in the Quincy area.

In 1812, Adams reconciled with Jefferson. Their mutual friend, Benjamin Rush who had been corresponding with both, encouraged Adams to reach out to Jefferson. Adams sent a brief note to Jefferson, which resulted in a resumption of their friendship, and initiated a correspondence which lasted the rest of their lives. Their letters are rich in insight into both the period and the minds of the two Presidents and revolutionary leaders.

Sixteen months before his death, his son, John Quincy Adams, became the sixth President of the United States (1825–1829), the only son of a former President to hold the office until George W. Bush in 2001.

His daughter Abigail was married to Congressman William Stephens Smith and died of cancer in 1816. His son Charles died as an alcoholic in 1800. His son Thomas and his family lived with Adams and Louisa Smith (Abigail's niece by her brother William) to the end of Adams' life.

Death

On July 4, 1826, the 50th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, Adams died in Quincy, Massachusetts. He is often quoted as having said "Thomas Jefferson still survives." with some depictions indicating he might have not expressed the entire statement before dying, i.e.,: "Thomas Jefferson… still survi—," but some research indicates that only the words "Thomas Jefferson" were clearly intelligible among his last. Adams did not know that Jefferson, his great political rival—and later friend and correspondent—had died a few hours earlier.

His crypt lies at United First Parish Church (also known as the Church of the Presidents) in Quincy. Until his record was broken by Ronald Reagan on October 10, 2001, he was the nation's longest-living President (90 years, 247 days).

Religious views

Adams was raised a Congregationalist, becoming a Unitarian at a time when most of the Congregational churches around Boston were turning to Unitarianism. As a youth, Adams' father had urged him to become a minister, but Adams considered the practice of law to be a more noble calling (although he did spend some time as a school teacher to pay the necessary fees to practice law).

Adams was not an orthodox believer, yet saw in the life a Christ a model of human perfection and believed in the essential goodness of the creation. Like many of the revolutionary generation, Adams was impatient with dogmas and supernatural claims. In a letter to Jefferson, Adams summed up his faith, writing, “My Adoration of the Author of the Universe is too profound and too sincere. The Love of God and his Creation; delight, Joy, Tryumph, Exaltation in my own existence, tho' but an Atom, a molecule Organique, in the Universe, are my religion.”

Adams rejected Christian doctrines of the trinity and predestination, and also railed against what he saw as overreaching authority by the Catholic Church. Yet Adams held a strong conviction in life after death—or otherwise, as he explained, “you might be ashamed of your Maker”—and he equated the human faculty of understanding and the conscience to “celestial communication,” or personal revelation from God.

Adams also saw the religion as a practical necessity and the underpinning of liberty. In a letter to his cousin Zabdiel Adams in June 1776, Adams wrote, "Statesmen, my dear Sir, may plan and speculate for liberty, but it is religion and morality alone, which can establish the principles upon which freedom can securely stand. The only foundation of a free Constitution is pure virtue, and if this cannot be inspired into our People in a greater Measure than they have it now, they may change their rulers and the forms of government, but they will not obtain a lasting liberty."[3]

Notes

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brown, Ralph A. The Presidency of John Adams. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. 1988 ISBN 0700601341 Political narrative.

- Chinard, Gilbert. Honest John Adams. Boston, MA: Little, Brown (1964). short life

- Elkins, Stanley M. and Eric McKitrick. The Age of Federalism. ONY: Oxford University Press, 1993 ISBN 0195068904. highly detailed a political narrative and interpretation focused on leading men

- Ellis, Joseph J. Passionate Sage: The Character and Legacy of John Adams. NY: Norton, 1993. ISBN 0393034798 a thoughtful interpretative essay by Pulitzer prize winning scholar.

- Ferling, John. Adams Vs. Jefferson: The Tumultuous Election of 1800. (2004), narrative and analytical history of the election.

- Ferling, John. John Adams: A Life. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1992 ISBN 0870497308 reliable biography that dabbles in psychobiography.

- Grant, James. John Adams: Party of One. NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005 ISBN 0374113149 balanced, thoughtful, and short

- Haraszti, Zoltan. John Adams and the Prophets of Progress. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1952 Brilliant and innovative investigation of Adams's political thought by reference to the arguments he waged with authors in the margins of their books.

- Kurtz, Stephen G. The Presidency of John Adams: The Collapse of Federalism, 1795-1800. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1957. Thorough political narrative.

- McCullough, David. John Adams. NY: Simon & Schuster, 2002 ISBN 0684813637 Best-selling popular biography, stressing Adams's character, his marriage with Abigail; skips over his ideas and his constitutional thoughts. Winner of the 2002 Pulitzer Prize in Biography.

- Miller, John C. The Federalist Era: 1789-1801. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, reprint 1998. ISBN 1577660315 Thorough discussion of politics in the decade 1789-1801.

- Sharp, James. American Politics in the Early Republic: The New Nation in Crisis. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993. ISBN 0300055307 detailed political narrative of 1790s.

- Smith, Page. John Adams. NY: Doubleday & Company, 1962. 2 volume biography, winner of the Bancroft Prize, with many charming but irrelevant details.

- Thompson, C. Bradley. John Adams and the Spirit of Liberty. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1998. ISBN 0700609156 Analysis of Adams's political thought; insists Adams was the greatest political thinker among the Founding Generation and anticipated many of the ideas in The Federalist.

Primary sources

- Adams, C.F. The Works of John Adams, with Life (10 vols., Boston: Little, Brown & Co, 1850-1856

- Butterfield, L. H. et al., eds., The Adams Papers Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press, 1961- 0674004000 (v. 1-2) ISBN 0674004051 (v. 3-4) ISBN 067400406X (v. 5-6) ISBN 0674015746 (v. 7) Multivolume letterpress edition of all letters to and from major members of the Adams family, plus their diaries; still incomplete [4].

- Cappon, Lester J. ed. The Adams-Jefferson Letters: The Complete Correspondence Between Thomas Jefferson and Abigail and John Adams. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988.

- Carey, George W., (ed.) The Political Writings of John Adams. Washington, DC: Regnery Pub, 2001. ISBN 0895262924 Compilation of extracts from Adams's major political writings.

- Diggins, John P., ed. The Portable John Adams. NY: Penguin Classics, 2004. ISBN 0142437786

External links

All links retrieved August 3, 2022.

- John Adams Quotes at Liberty-Tree.ca

- The Papers of John Adams from the Avalon Project (includes Inaugural Address, State of the Union Addresses, and other materials)

- Adams Family Papers: An electronic archive

- State of the Union Addresses: 1797, 1798, 1799, 1800

- Medical and Health History of John Adams

- John Adams Jewish Encyclopedia

| Preceded by: (none) |

Federalist Party vice presidential candidate 1792 (won) (a), (b) |

Succeeded by: Thomas Pinckney (b) |

| Preceded by: (none) |

Vice President of the United States April 21, 1789(c)–March 4, 1797 |

Succeeded by: Thomas Jefferson |

| Preceded by: —(d) |

Federalist Party presidential candidate 1796 (won), 1800 (lost) |

Succeeded by: Charles Cotesworth Pinckney |

| Preceded by: George Washington |

President of the United States March 4, 1797–March 4, 1801 |

Succeeded by: Thomas Jefferson |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 19:20:54 | 201 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/John_Adams | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF