Giraffe

From Nwe

From Nwe | Giraffe | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Giraffa camelopardalis Linnaeus, 1758 |

||||||||||||||

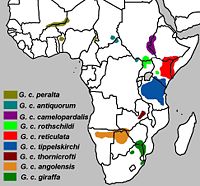

Range map

|

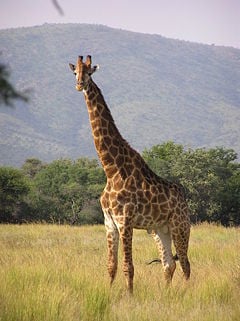

The giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis), an African even-toed ungulate mammal, has a very long neck and legs and is the tallest of all land-living animal species. Males can be 4.8 to 5.5 meters (16 to 18 feet) tall and weigh up to 1,360 kilograms (3,000 pounds). Females are generally slightly shorter (up to 4.3 meters or 14 feet) and weigh less than the males do (up to 680 kilograms or 1,500 pounds) (ZSSD 2007). Giraffes also have the longest tail of any land mammal (up to 2.4 meters or 8 feet) and a spotted pattern reminiscent of the leopard (which ties to the origin of the species name) (ZSSD 2007).

Giraffes play an unique role in the ecosystem by consuming leaves too high for use by most animals and by sometimes serving as an "early-warning" system for near-by animals regarding the presence of predators. Giraffes have been described in early written records as being "magnificent in appearance, bizarre in form, unique in gait, colossal in height and inoffensive in character," and have been revered in ancient cultures and even some modern cultures (AWF 2007).

The giraffe is native to most of Sub-Saharian Africa with its range extending from Chad to South Africa. Within the last century, anthropogenic activities have nearly eliminated the giraffe from its former range in Western Africa; but it does remain common in eastern and southern Africa, with a total population estimated at 141,000 (Grzimek 2004).

As an even-toed ungulate (order Artiodactyla), the giraffe is related to deer and cattle, but it is placed in a separate family, the Giraffidae, comprising only the giraffe and its closest relative, the okapi.

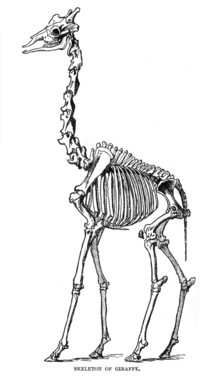

Description

Giraffes are the tallest land animals, reaching 5.5 meters (18 feet). The legs and neck are very long, each about 1.8 meters (six feet) in length. While the basic body pattern is the back sloping down to the hindquarters, with the back legs looking shorter than the front legs, the back and front legs actually are about the same length (ZSSD 2007). Like humans, giraffes have seven neck vertebrae; unlike human neck vertebrae, giraffe neck vertebrae can each be over 25 centimeters (ten inches) long (ZSSD 2007).

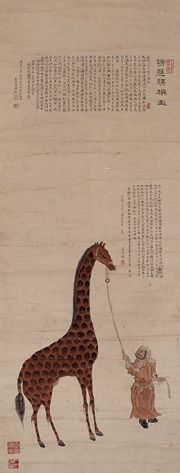

Giraffes have spots covering their entire bodies, except their underbellies, with each giraffe having a unique pattern of spots. Because this spotted pattern is similar to that of a leopard, for a long time people called the giraffe a “camel-leopard,” thinking it to be a cross of a camel and a leopard, leading to the species name camelopardalis (AWF 2007; ZSSD 2007). The linking of giraffe, leopard, and camel traces back to at least the Romans and the English word camelopard first appeared in the fourteenth century and survived in common usage well into the nineteenth century. A number of European languages retain it. (The Arabic word الزرافة ziraafa or zurapha, meaning "assemblage" (of animals), or just "tall," was used in English from the sixteenth century on, often in the Italianate form giraffa).

Giraffe's have long (46 centimeter or 18 inch), prehensile, blue-black tongues that they can use to maneuver around the long thorns of the acacia trees in order to reach the leaves on which they feed. They also have thick, sticky saliva that coats any thorns they might swallow (ZSSD 2007). It is thought that the dark color of their tongues protects them from getting sunburned while reaching for leaves on trees (ZSSD 2007). Giraffes also have large eyes.

Both sexes have skin-covered horns (really knobs), although the horns of a female are smaller. The prominent horns are formed from ossified cartilage and are called ossicones. The appearance of the horns is a reliable method of identifying the sex of giraffes, with the females displaying tufts of hair on the top of the horns, whereas males' horns tend to be bald on top—an effect of necking in combat with other males. Males sometimes develop calcium deposits that form large bumps on their skull as they age, which can give the appearance of up to three further horns (ZSSD 2007).

Physiological adaptations, particularly in the circulatory system, permit the giraffe's large size. A giraffe's heart, which can be 0.6 meters in length (two feet) and weigh up to 11 kg (25 lb), has to generate around double the normal blood pressure for an average large mammal in order to maintain blood flow to the brain against gravity. In the upper neck, a complex pressure-regulation system called the rete mirabile prevents excess blood flow to the brain when the giraffe lowers its head to drink. Conversely, the blood vessels in the lower legs are under great pressure (because of the weight of fluid pressing down on them). In other animals such pressure would force the blood out through the capillary walls; giraffes, however, have a very tight sheath of thick skin over their lower limbs that maintains high extravascular pressure. The giraffe's lungs can hold 12 gallons (55 liters) of air (ZSSD 2007).

As in most members of the order Artiodactyla (even-toed ungulates), giraffes digest their food by the process of rumination. Their stomachs are divided into four chambers (Walker et al. 1983). After food is swallowed, it is kept in the first chamber for a while where it is partly digested with the help of microorganisms. In this symbiotic relationship, the microorganisms break down the cellulose in the plant material into carbohydrates, which the giraffe can digest. Both sides receive some benefit from this relationship. The microorganisms get food and a place to live and the giraffe gets help with its digestion. The partly digested food is then sent back up to the mouth where it is chewed again and sent on to the other parts of the stomach to be completely digested. The microorganisms themselves are also digested, providing proteins and other nutrients, but not before the community of microorganisms has had a chance to reproduce and give rise to a new generation so the relationship can continue (Lott 2003).

Behavior

The giraffe browses selectively on more than 100 species of trees and shrubs (Grzimek et al. 2004), preferring plants of the genus Mimosa. In Southern Africa, giraffes are partial to all acacias, especially Acacia erioloba. A giraffe can eat 63 kg (140 lb) of leaves and twigs daily. The high water content in acacia leaves allows giraffes to go a long time without drinking (ZSSD 2007).

The pace of the giraffe is an amble, though when pursued it can run extremely fast, around 30 miles an hour (48 km/hr) (ZSSD 2007). It can not sustain a lengthened chase. A giraffe moves in a gait where both the front and back legs on one side move foward at the same time, and then the two legs on the other side move forward (ZSSD 2007). Its leg length compels an unusual gait: at low speed, the left legs move together followed by right (similar to pacing), while at high speed the back legs cross outside the front.

Giraffes are hunted only by lions and crocodiles (ZSSD 2007). The giraffe can defend itself against threats by kicking with great force. A single well-placed kick of an adult giraffe can shatter a lion's skull or break its spine.

The giraffe has one of the shortest sleep requirements of any mammal, which is between ten minutes and two hours in a 24-hour period, averaging 1.9 hours per day (BBC 2007). This has led to the myth that giraffes cannot lie down and that if they do so, they will die.

Giraffes are thought to be mute; however, although generally quiet, they have been heard to grunt, snort and bleat. Recent research has shown evidence that the animal communicates at an infrasound level (von Muggenthaler et al. 1999).

Giraffes are one of the very few animals that cannot swim at all.

Social structure, reproductive behavior and life cycle

Female giraffes associate in groups of a dozen or so members, up to 20, occasionally including a few younger males. Males tend to live in "bachelor" herds, with older males often leading solitary lives. Reproduction is polygamous, with a few older males impregnating all the fertile females in a herd. Male giraffes determine female fertility by tasting the female's urine in order to detect estrus, in a multi-step process known as the flehmen response.

Females can get pregnant in their fourth year, with at least 16 months, usually 20 months, between births (Grzimek et al. 2004). Giraffe gestation lasts between 14 and 15 months, after which a single calf is born.

The mother gives birth standing up and the embryonic sack usually bursts when the baby falls to the ground headfirst. Newborn giraffes are about 1.8 meters tall. Within a few hours of being born, calves can run around and are indistinguishable from a week-old calf; however, for the first two weeks, they spend most of their time lying down, guarded by the mother. Sometimes the calf is left alone for most of the day by the mother, with the calf remaining quiet until the mother returns (ZSSD 2007). When calves are older, several calves may be left with one mother to guard them while they eat (ZSSD 2007). Young giraffes can eat leaves at the age of four months (ZSSD 2007).

While adult giraffes are too large to be attacked by most predators, the young can fall prey to lions, leopards, hyenas, and African Wild Dogs. It has been speculated that their characteristic spotted pattern provides a certain degree of camouflage. Only 25 to 50 percent of giraffe calves reach adulthood; the life expectancy is between 20 and 25 years in the wild and up to 28 years in captivity (McGhee and McKay 2007).

The males often engage in necking, which has been described as having various functions. One of these is combat. These battles can be fatal, but are more often less severe. The longer a neck is, and the heavier the head at the end of the neck, the greater force a giraffe will be able to deliver in a blow. It has also been observed that males that are successful in necking have greater access to estrous females, so that the length of the neck may be a product of sexual selection (Simmons and Scheepers 1996). After a necking duel, a giraffe can land a powerful blow with his head occasionally knocking a male opponent to the ground. These fights rarely last more than a few minutes or end in physical harm.

Classification

There are nine generally accepted subspecies, although the taxonomy is not fully agreed (Grzimek et al. 2004). These subspecies are differentiated by color and pattern variations and by range:

- Reticulated or Somali giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis reticulata)—large, polygonal liver-colored or chestnut-covered spots outlined by a network of thin, white lines. The blocks may sometimes appear deep red and may also cover the legs. Range: northeastern Kenya, Ethiopia, Somalia.

- Angolan or smoky giraffe (G. c. angolensis)—large spots and some notches around the edges, extending down the entire lower leg. Range: southern Angola, Zambia, northern Namibia, and western Botswana.

- Kordofan giraffe (G. c. antiquorum)—smaller, more irregular spots that cover the inner legs. Range: western and southwestern Sudan.

- Masai or Kilimanjaro giraffe (G. c. tippelskirchi)—jagged-edged, vine-leaf or star-shaped spots of dark chocolate, brown, or tan on a yellowish background. Most irregular pattern. Range: central and southern Kenya, Tanzania.

- Nubian giraffe (G. c. camelopardalis)—large, four-sided spots of chestnut brown on an off-white background and no spots on inner sides of the legs or below the hocks. Range: eastern Sudan, northeast Congo.

- Rothschild giraffe or Baringo giraffe or Ugandan giraffe (G. c. rothschildi)—deep brown, blotched, or rectangular spots with poorly defined cream lines. Hocks may be spotted; no spotting below knees. Range: Uganda, western and north-central Kenya.

- South African giraffe (G. c. giraffa)—rounded or blotched spots, some with star-like extensions on a light tan background, running down to the hooves. Range: South Africa, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mozambique.

- Thornicroft or Rhodesian giraffe (G. c. thornicrofti)—star-shaped or leafy spots extend to the lower leg. Range: eastern Zambia.

- West African or Nigerian Giraffe (G. c. peralta)—numerous pale, yellowish red spots. Range: Niger, Cameroon.

Some scientists regard Kordofan and West African giraffes as a single subspecies; similarly with Nubian and Rothschild's giraffes, and with Angolan and South African giraffes. Further, some scientists regard all populations except the Masai Giraffes as a single subspecies. By contrast, some scientists have proposed four other subspecies—Cape giraffe (G. c. capensis), Lado giraffe (G. c. cottoni), Congo giraffe (G. c. congoensis), and Transvaal giraffe (G.c. wardi)—but none of these is widely accepted.

Gallery

-

Giraffe family, Aalborg Zoo, Denmark.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- African Wildlife Foundation (AWF). Giraffe. African Wildlife Foundation. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- British Broadcasting Company. 2014. The science of sleep. BBC. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- Grzimek, B., D. G. Kleiman, V. Geist, and M. C. McDade. 2004. Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Detroit: Thomson-Gale. ISBN 0787657883

- Lott, D. F. 2002. American Bison. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520233387

- McGhee, K., and G. McKay. 2007. Encyclopedia of Animals. Washington, DC: National Geographic. ISBN 0792259378

- Simmons, R. E., and L. Scheepers. 1996. Winning by a neck: Sexual selection in the evolution of giraffe. The American Naturalist 148: 771-786.

- von Muggenthaler, E., C. Baes, D. Hill, R. Fulk, and A. Lee. 1999. Infrasound and low frequency vocalizations from the giraffe; Helmholtz resonance in biology. Animal Voice. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

- Walker, E. P., R. M. Nowak, and J. L. Paradiso. 1983. Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801825253

- Zoological Society of San Diego (ZSSD). 2016. Mammals: Giraffe. Zoological Society of San Diego. Retrieved September 14, 2016.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 02:14:26 | 9 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Giraffe | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF