Grievances Of The United States Declaration Of Independence

From Conservapedia

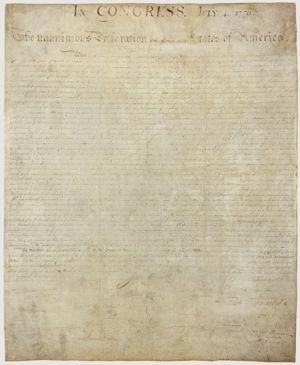

From Conservapedia The Declaration of Independence is among other things a compilation of twenty seven grievances against the British Crown. Historians have noted the similarities with John Locke's works and the context of the grievances.[1] For generations, well established traditions as well as proclamations such as the Magna Carta, the English Bill of Rights and others, signify to the people that the King is not to interfere with the Rights of Englishmen held by the people. At the time of the founding, such early documents and sentiments were well known by the people. By opposing laws deemed necessary for the public good and by constantly meddling in the local affairs of the colonists, the King opposed the end or purpose of government.[1] Below is each grievance contained within the Declaration, and a summary of what it is in reference to.

Contents

- 1 Grievance 1

- 2 Grievance 2

- 3 Grievance 3

- 4 Grievance 4

- 5 Grievance 5

- 6 Grievance 6

- 7 Grievance 7

- 8 Grievance 8

- 9 Grievance 9

- 10 Grievance 10

- 11 Grievance 11

- 12 Grievance 12

- 13 Grievance 13

- 14 Grievance 14

- 15 Grievance 15

- 16 Grievance 16

- 17 Grievance 17

- 18 Grievance 18

- 19 Grievance 19

- 20 Grievance 20

- 21 Grievance 21

- 22 Grievance 22

- 23 Grievance 23

- 24 Grievance 24

- 25 Grievance 25

- 26 Grievance 26

- 27 Grievance 27

- 28 References

- 29 External links

Grievance 1[edit]

- He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.

The Colonial Assemblies, from time to time, made enactments touching their commercial operations, the emission of a colonial currency, and concerning representatives in the imperial Parliament, but the assent of the sovereign to these laws was withheld. After the Stamp-Act excitements, Secretary Conway informed the Americans that the tumults should be overlooked, provided the Assemblies would make provision for full compensation for all public property which had been destroyed. In complying with this demand, the Assembly of Massachusetts thought it would be "wholesome and necessary for the public good," to grant free pardon to all who had been engaged in the disturbances, and passed an act accordingly. It would have produced quiet and good feeling; but the royal assent was refused.[2]

Grievance 2[edit]

- He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.

Similar to the first grievance, this is an indictment for the King's men in the colonies who have refused to assent to laws conducive to the public good. For example, in 1764, the Assembly of New York took measures to conciliate the Six Nations, and other Indian tribes. The motives of the Assembly were misconstrued, representations having been made to the king that the colonies wished to make allies of the Indians, so as to increase their physical power and proportionate independence of the British crown. The monarch sent instructions to all his governors to desist from such alliances, or to suspend their operations until his assent should be given. He then "utterly neglected to attend to them." The Massachusetts Assembly passed a law in 1770, for taxing officers of the British government in that colony. The governor was ordered to withhold his assent to such tax-bill. This was in violation of the colonial charter, and the people justly complained. The Assembly Was prorogued from time to time, and laws of great importance were "utterly neglected."[2]

"Neglect" is one of two reasons mentioned by Locke as a valid reason for dissolving government.[1]

Grievance 3[edit]

- He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only.

As noted in Chapter 19 of Two Treatises of Government, "when such a single person, or prince, sets up his own arbitrary will, in place of the laws, which are the will of the society, declared by the legislative, then the legislative is changed." The changing of the legislature without the people's knowledge or without their consent is another way government is then dissolved. Government for the public good is only by the people, and not what is good for the rulers.[1]

Grievance 4[edit]

- He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their Public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures.

On May 20, 1774, Parliament passed the Massachusetts Government Act, which nullified the Massachusetts Charter of 1691[3] and allowed governor Thomas Gage to dissolve the local provincial assembly and force them to meet in Salem.[4]

Grievance 5[edit]

- He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people.

When the British government became informed of the fact that the Assembly of Massachusetts in 1768 had issued a circular to other Assemblies, inviting their co operation in asserting the principle that Great Britain had no right to tax the colonists without their consent, Lord Hillsborough, the Secretary for Foreign Affairs, was directed to order the governor of Massachusetts to require the Assembly of that province to rescind its obnoxious resolutions expressed in the circular. In case of their refusal to do so, the governor was ordered to dissolve them immediately. Other Assemblies were warned not to imitate that of Massachusetts, and when they refused to accede to the wishes of the king, as expressed by the several royal governors, they were repeatedly dissolved. The Assemblies of Virginia and North Carolina were dissolved for denying the right of the king to tax the colonies, or to remove offenders out of the country for trial. In 1774, when the several Assemblies entertained the proposition to elect delegates to a general Congress, nearly all of them were dissolved.[2]

On May 31, 1765, the Virginia House of Burgesses was dissolved by Royal Governor Francis Fauquier.[5]

Grievance 6[edit]

- He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected, whereby the Legislative Powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within.

When the Assembly of New York, in 1766, refused to comply with the provisions of the Mutiny Act, its legislative functions were suspended by royal authority, and for several months the State remained "exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without and convulsions within." The Assembly of Massachusetts after its dissolution in July, 1768, was not permitted to meet again until the last Wednesday of May, 1769, and then they found the place of meeting surrounded by a military guard, with cannons pointed directly at their place of meeting. They refused to act under such tyrannical restraint and their legislative power returned to be people.[2]

Grievance 7[edit]

- He has endeavored to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands.

Secret agents were sent to America soon after the accession of George the Third to the throne of England, to spy out the condition of the colonists. A large influx of liberty-loving German emigrants was observed, and the king was advised to discourage these immigrations. Obstacles in the way of procuring lands, and otherwise, were put in the way of all emigrants, except from England, and the tendency of French Roman Catholics to settle in Maryland was also discouraged. The British government was jealous of the increasing power of the colonies; and the danger of having that power controlled by democratic ideas, caused the employment of restrictive measures. The easy conditions upon which actual settlers might obtain lands on the Western frontier, after the peace of 1763, were so changed that toward the dawning of the Revolution, the vast solitudes west of the Alleghenies were seldom penetrated by any but the hunter from the seaboard provinces. When the War for Independence broke out, immigration had almost ceased. The king conjectured wisely, for almost the entire German population in the colonies were on the side of the patriots.[2]

Grievance 8[edit]

- He has obstructed the Administration of Justice by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary Powers.

By an act of Parliament in 1774, the judiciary was taken from the people of Massachusetts. The judges were appointed by the king, were dependent on him for their salaries, and were subject to his will. Their salaries were paid from moneys drawn from the people by the commissioners of customs, in the form of duties. The same act deprived them, in most cases, of the benefit of trial by jury, and the "administration of justice" was effectually obstructed. The rights for which Englishmen so manfully contended in 1688 were trampled under foot. Similar grievances concerning the courts of law existed in other colonies; and throughout the Anglo-American domain there was but a semblance of justice left. The people met in conventions when Assemblies were dissolved, and endeavored to establish "judiciary powers" but in vain; and were finally driven to rebellion.[2]

Grievance 9[edit]

- He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries.

As we have observed, judges were made independent of the people. Royal governors were placed in the same position. Instead of checking their tendency to petty tyranny, by having them depend upon the Colonial Assemblies for their salaries, these were paid out of the national treasury. Independent of the people they had no sympathies with the people, and thus became fit instruments of oppression, and ready at all times to do the bidding of the king and his ministers. The Colonial Assemblies protested against the measure, and out of the excitement which it produced grew that power of the Revolution, the Committees of Correspondence. In 1774, when Chief Justice Oliver of Massachusetts declared it to be his intention to receive his salary from the crown, the Assembly proceeded to impeach him and petitioned the governor for his removal. The governor refused compliance and great irritation ensued.[2]

Grievance 10[edit]

- He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people and eat out their substance.

After the passage of the Stamp Act, stamp distributors were appointed in every considerable town. In 1766 and 1767, acts for the collection of duties created "swarms of officers", all of whom received high salaries; and when in 1768, admiralty and vice admiralty courts were established on a new basis, an increase in the number of officers was made. The high salaries and extensive perquisites of all of these, were paid with the people's money, and thus "swarms of officers" "eat out their substance."[2]

Grievance 11[edit]

- He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures.

After the treaty of peace with France, in 1763, Great Britain left quite a large number of troops in America, and required the colonists to contribute to their support. There was no use for this standing army, except to repress the growing spirit of Republicanism among the colonists, and to enforce compliance with taxation laws. The presence of troops was always a cause of complaint; and when, finally, the colonists boldly opposed the unjust measures of the British government, armies were sent hither to awe the people into submission. It was one of those "standing armies" kept here "without the consent of the Legislature," against which the patriots at Lexington, and Concord, and Bunker Hill so manfully battled in 1775.[2]

Grievance 12[edit]

- He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil Power.

General Gage, commander-in chief of the British forces in America, was appointed governor of Massachusetts in 1774; and to put the measures of the Boston Port Bill into execution, he encamped several regiments of soldiers upon Boston Common. The military there, and also in New York, was made independent of, and superior to, the civil power, and this, too, in a time of peace, before the Minute-men were organized.[2]

Grievance 13[edit]

- He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation:

The "others" with whom the King is thus said to have combined were, of course, the British Parliament, the existence of which as a legally constituted body possessing authority over them the Americans thus refused even by implication to recognise.[6] This was because of the establishment of a Board of Trade, to act independent of colonial legislation through its creatures (resident commissioners of customs) in the enforcement of revenue laws. This was altogether foreign to the constitution of any of the colonies, and produced great indignation. The establishment of this power, and the remodeling of the admiralty courts so as to exclude trial by jury therein, in most cases rendered the government fully obnoxious to the charge in the text. The people felt their degradation under such petty tyranny, and resolved to spurn it. It was effectually done in Boston, and the government, after all its bluster, was obliged to recede. In 1774, the members of the council of Massachusetts (answering to our Senate), were, by a Parliamentary enactment, chosen by the king, to hold the office during his pleasure. Almost unlimited power was also given to the governor, and the people were indeed subjected to "a jurisdiction foreign to their constitution " by these creatures of royalty.[2]

Grievance 14[edit]

- For quartering large bodies of armed troops among us:

In 1774 seven hundred troops were landed in Boston, under cover of the cannons of British armed ships in the harbor; and early the following year, Parliament voted ten thousand men for the American service, for it saw the wave of rebellion rising high under the gale of indignation which unrighteous acts had spread over the land. The tragedies at Lexington and Concord soon followed, and at Bunker Hill the War for Independence was opened in earnest.[2]

Grievance 15[edit]

- For protecting them, by a mock Trial from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States:

In 1768, two citizens of Annapolis, in Maryland, were murdered by some marines belonging to a British armed ship. The trial was a mockery of justice; and in the face of clear evidence against them, the criminals were acquitted. In the difficulties with the Regulators in North Carolina, in 1771, some of the soldiers who had shot down citizens when standing up in defence of their rights, were tried for murder and acquitted; while Governor Tryon mercilessly hung six prisoners, who were certainly entitled to the benefits of the laws of war, if his own soldiers were.[2]

Grievance 16[edit]

- For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world:

The navigation laws were always oppressive in character. In 1764, the British naval commanders having been clothed with the authority of custom-house officers, completely broke up a profitable trade which the colonists had long enjoyed with the Spanish and French West Indies, notwithstanding it was in violation of the old Navigation Act of 1660, which had been almost ineffectual. Finally, Lord North concluded to punish the refractory colonists of New England, by crippling their commerce with Great Britain, Ireland, and the West Indies. Fishing on the banks of Newfoundland was also prohibited, and thus, as far as Parliamentary enactments could accomplish it, their "trade with all parts of the world" was cut off.[2]

Grievance 17[edit]

- For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:

In addition to the revenue taxes imposed from time to time and attempted to be collected by means of writs of assistance, the Stamp Act was passed, and duties upon paper, painters' colors, glass, tea, etc., were levied. This was a great bone of contention between the colonists and the imperial government. It was contention on the one hand for the great political truth that taxation and representation are inseparable, and a lust for power and the means for replenishing an exhausted treasury, on the other. The climax of this contention was the Revolution.[2]

Grievance 18[edit]

- For depriving us in many cases, of the benefit of Trial by Jury:

This was especially the case when commissioners of customs were concerned in the suit. After these functionaries were driven from Boston in 1768, an act was passed which placed violations of the revenue laws under the jurisdiction of the admiralty courts, where the offenders were tried by a creature of the crown, and were deprived "of the benefits of trial by jury."[2]

Grievance 19[edit]

- For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offenses:

On the fifteenth of April, 1774, Lord North introduced a bill in Parliament, entitled " A bill for the impartial administration of justice in the cases of persons questioned for any acts done by them in the execution of the laws, or for the suppression of riots and tumults in the province of Massachusetts Bay, in New England." This bill, known as the Administration of Justice Act, provided that in case any person indicted for murder in that province, or any other capital offence, or any indictment for riot, resistance of the magistrate, or impeding the revenue laws in the smallest degree, he might, at the option of the Governor, or, in his absence, of the Lieutenant Governor, be taken to another colony, or transported to Great Britain, for trial, a thousand leagues from his friends, and amidst his enemies.

The arguments used by Lord North in favor of the measure, had very little foundation in either truth or justice, and the bill met with violent opposition in parliament. The minister seemed to be actuated more by a spirit of retaliation, than by a conviction of the necessity of such a measure. "We must show the Americans," said he, ' that we will no longer sit quietly under their insults; and also, that even when roused, our measures are not cruel or vindictive, but necessary and efficacious." Colonel Barre, who, from the first commencement of troubles with America, was the fast friend of the colonists, denounced the bill in unmeasured terms, as big with misery, and pregnant with danger to the British Empire. "This," said he, "is indeed the most extraordinary resolution that was ever heard in the Parliament of England. It offers new encouragement to military insolence, already so insupportable. By this law, the Americans are deprived of a right which belongs to every human creature, that of demanding justice before a tribunal composed of impartial judges."[7]

The text of the bill contained the following:

In that case, it shall and may be lawful for the governor, or lieutenant-governor, to direct, with the advice and consent of the council, that the inquisition, indictment, or appeal, shall be tried in some other of his Majesty's colonies, or in Great Britain.[8]

Grievance 20[edit]

- For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies

This charge is embodied in an earlier one. The British ministry thought it prudent to take early steps to secure a footing in America so near the scene of inevitable rebellion as to allow them to breast, successfully, the gathering storm. The investing of a legislative council in Canada with all powers except levying of taxes, was a great stride toward that absolute military rule which bore sway there within eighteen months afterward. Giving up their political rights for doubtful religious privileges, made them willing slaves, and Canada remained a part of the British empire when its sister colonies rejoiced in freedom.[2]

Grievance 21[edit]

- For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments:

This is a reiteration of a charge already considered, and refers to the alteration of the Massachusetts charter, so as to make judges and other officers independent of the people, and subservient to the crown. The governor was empowered to remove and appoint all inferior judges, the attorney-generals, provost-marshals, and justices of the peace, and to appoint sheriffs independent of the council. As the sheriffs chose jurors, trial by jury might easily be made a mere mockery. The people had hitherto been allowed, by their charter, to select jurors; now the whole matter was placed in the hands of the creatures of government.[2]

Grievance 22[edit]

- For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever.

This, too, is another phase of the charge just considered. We have noticed the suppression of the Legislature of New York, and in several cases, the governors, after dissolving Colonial Assemblies, assumed the right to make proclamations stand in the place of statute law. Lord Dunmore assumed this right in 1775, and so did Sir James Wright of Georgia, and Lord William Campbell of South Carolina. They were driven from the country in consequence.[2]

Grievance 23[edit]

- He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us.

In his message to Parliament early in 1775, the king declared the colonists to be in a state of open rebellion; and by sending armies hither to make war upon them, he really "abdicated government," by thus declaring them "out of his protection." He sanctioned the acts of governors in employing the Indians against his subjects, and himself bargained for the employment of German hirelings. And when, yielding to the pressure of popular will, his representatives (the royal governors) fled before the indignant people, he certainly "abdicated government."[2]

Grievance 24[edit]

- He has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.

When naval commanders were clothed with the powers of custom house officers, they seized many American vessels; and after the affair at Lexington and Bunker Hill, British ships of war "plundered our seas" wherever an American vessel could be found. They also "ravaged our coasts and burnt our towns." Charlestown, Falmouth (now Portland, in Maine), and Norfolk were burnt, and Dunmore and others "ravaged our coasts," and "destroyed the lives of our people." And at the very time when this Declaration was being read to the assembled Congress, the shattered fleet of Sir Peter Parker was sailing northward, after an attack upon Charleston, South Carolina.[2]

Grievance 25[edit]

He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to complete the works of death, desolation, and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & Perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.

The hire of Hessian Soldiers as mercenaries for use against the Thirteen Colonies, see the May 15th preamble.[9]

Grievance 26[edit]

He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands.

An act of Parliament passed toward the close of December, 1775, authorized the capture of all American vessels, and also directed the treatment of the crews of armed vessels to be as slaves and not as prisoners of war. They were to be enrolled for "the service of his majesty," and were thus compelled to fight for the crown, even against their own friends and countrymen. This act was loudly condemned on the floor of Parliament as unworthy of a Christian people, and "a refinement of cruelty unknown among savage nations."[2]

Grievance 27[edit]

He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions.

This was done in several instances, Dunmore was charged with a design to employ the Indians against the Virginians as early as 1774; and while ravaging the Virginia coast in 1775 and 1776, he endeavored to excite the slaves against their masters. He was also concerned with Governor Gage and others, under instructions from the British ministry, in exciting the Shawnetse, and other savages of the Ohio country, against the white people. Emissaries were also sent among the Cherokees and Creeks for the same purpose; and all of the tribes of the Six Nations, except the Oneidas, were found in arms with the British when war began. Thus excited, dreadful massacres occurred on the borders of the several colonies.[2]

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Jefferson's Declaration of Independence: Origins, Philosophy, and Theology

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 Our Country: A Household History for All Readers, from the Discovery of America to the Present Time, Volume 1, by Benson John Lossing

- ↑ Liberty, Equality, Power: A History of the American People, Volume I: To 1877, Concise Edition

- ↑ Lexington: From Liberty's Birthplace to Progressive Suburb

- ↑ Profiles in Colonial History

- ↑ The Fortnightly, Volume 34

- ↑ Lives of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence, p. 292

- ↑ Administration of Justice Act

- ↑ Letters of Delegates to Congress: Volume: 3 January 1, 1776 - May 15, 1776 - John Adams to James Warren, May 15th, 1776

External links[edit]

- An answer to the Declaration of the American Congress, by John Lind and Jeremy Bentham

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Categories: [United States History] [American Revolution] [American State Papers] [Republicanism]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 03/01/2023 14:09:55 | 36 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Grievances_of_the_United_States_Declaration_of_Independence | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF