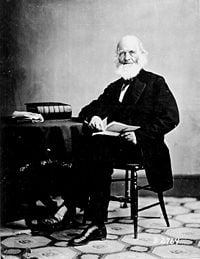

William Cullen Bryant

From Nwe

From Nwe

William Cullen Bryant (November 3, 1794 - June 12, 1878) was an American poet and newspaper editor who achieved literary fame at age 17, after writing the poem, "Thanatopsis." He went on to become one of the most influential journalists of the nineteenth century as editor-in-chief of the New York Evening Post, a career that spanned fifty years.

In addition to his contribution to romantic poetry, his essays promoted liberal causes and profoundly shaped American thought and politics in the nineteenth century. He was a widely read, and popular figure of the era, and in his later years, served as president of the New York Homeopathic Society.[1]

Historian Vernon Louis Parrington, author of Main Currents in American Thought (1927) called Bryant, "the father of nineteenth century American journalism as well as the father of nineteenth century American poetry."

Life

Youth and education

Bryant was born in Cummington, Massachusetts, the second son of Peter Bryant, a doctor and later a state legislator, and Sarah Snell. His maternal ancestry traced back to passengers on the Mayflower and his father's to colonists who arrived about a dozen years later. Although raised in the Calvinist heritage, his father broke with tradition by joining the more liberal denomination of Unitarianism. However, the Bryant family was united in their zeal for Federalist politics, a party headed by Alexander Hamilton in the late eighteenth century. Some Federalists, who believed in a strong national government, were at that time also pro-British.

Encouraged by his father to write poetry, the young neophyte penned a Federalist satire on then-President Thomas Jefferson called, The Embargo (1808). Jefferson was not only a leader of the Democratic-Republicans (1797), a party that opposed the Federalists, but he also upheld an embargo on trade with Great Britain. The poem was published by his father, then a Massachusetts state legislator. In later years, as a firmly established liberal, Bryant put distance between himself and the piece and it was never reprinted in any of his poetry collections.

In 1810, he entered Williams College, but left after a year. He furthered his education by studying with a lawyer near Cummington, as this was an established practice at that time. He was admitted to the bar in 1815, at the age of twenty.

From 1816 to 1825, he practiced law in Plainfield and Great Barrington, Massachusetts, but felt ill-suited for the law profession as he would "be troubled when he witnessed injustice in the court system and could not correct wrongs done to those whom he believed innocent."[2]

Influences and poetry

"Thanatopsis," (literally "view of death") his most famous poem, was written when he was only 17 years of age. The poem's underlying theme, which equates humanity's mortality with nature's transience, is noted for being "un-Christian-like" for its time.[3] In form and tone, it reflects the influence of English "graveyard" poets such as Thomas Gray and the neoclassic poet Alexander Pope. Soon after writing Thanatopsis, Bryant was influenced by romantic British poets, William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Many of Bryant's poems reflect his love for nature. Like the Romantics, he saw nature as a vital force in humanity's life. Poems written in that vein include: "Green River," "A Winter Piece," "The Death of Flowers," and "The Prairies."

"Thanatopsis," although mistakenly attributed to his father initially, was published by the North American Review in 1817, and was well received. Its closing stanza advises one on the threshold of death to:

- So live, that, when thy summons comes to join

- The innumerable caravan that moves

- To that mysterious realm where each shall take

- His chamber in the silent halls of death,

- Thou go not, like the quarry slave at night,

- Scourged to his dungeon, but sustained and soothed

- By an unfaltering trust, approach thy grave—

- Like one that draws the drapery of his couch

- About him and lies down to pleasant dreams.

His first book, simply entitled Poems, was published in 1821, and contains his longest poem, The Ages, consisting of thirty-five Spenserian stanzas, tracing the evolution of western civilization.

From the sixth stanza written in Iambic Pentameter:

- Look on this beautiful world and read the truth

- In her fair page; see, every season brings

- New change to her of everlasting youth;

- Still the green soil with joyous living things

- Swarms; the wide air is full of joyous wings;

- And myriads still are happy in the sleep

- Of Ocean's azure gulfs and where he flings

- The restless surge. Eternal Love doth keep

- In his complacent arms, the earth, the air, the deep.

Like other writers of the era, Bryant was seeking a uniquely singular American voice with his writing, which could be set apart from the culture of the mother country, England. In a lecture before the New York Athenaeum Society (1826), he said that poetic models of the past "which the poet chooses to follow should be used only as guides to his own originality." Bryant felt that although America did not have the historical and cultural heritage to draw upon as in England, a poet should draw on "the best the young country has to offer."[4] By 1932, Bryant had accomplished this goal himself, when—with the assistance of the already established literary figure, Washington Irving, who helped him publish Poems in England—he won recognition as America's leading poet.

Marriage and editorial career

On January 11, 1821, at the age of 26, Bryant married Francis Fairchild. They had two daughters, Frances and Julia. In 1825, the family moved to New York City, where Bryant decided to use his literary skills to pursue a career in journalism. The family also owned a home they called Cedarmere, on Long Island's Hempstead Harbor, where Bryant would engage in his favorite past time, taking long walks in the woods. The family frequently took trips abroad and when his wife fell ill in Italy, Bryant treated her with homeopathic remedies. Bryant's wife died in 1866. Bryant survived his wife by twelve years, working well into his 70's at the helm of the New York Evening Post where he became editor-in-chief and part owner (1828-78).

With the help of a distinguished and well-connected literary family, the Sedgwicks, he gained a foothold in New York City, where, in 1825, he was hired as editor, first of the New York Review, then of the United States Review and Literary Gazette. After two years, he became Assistant Editor of the New York Evening Post, a newspaper founded by Alexander Hamilton that was surviving precariously. Within two years, he was Editor-in-Chief and a part owner.

As an editor, he exerted considerable influence in support of liberal causes of the day, including antislavery, and free trade among nations. His editorials, decrying the corruption of the rich, were popular with the working class. In 1835, he wrote an editorial called The Right of Workmen to Strike, in which he upheld the worker's right to collective bargaining and ridiculed the prosecution of labor unions. "Can anything be imagined more abhorrent to every sentiment of generosity or justice, than the law which arms the rich with the legal right to fix…the wages of the poor? If this is not slavery we have forgotten its definition."[5]

When the Free Soil Party became a core of the new Republican Party in 1856, Bryant vigorously campaigned for John C. Fremont. In 1860, he was a strong supporter of Abraham Lincoln, whom he introduced at a speech at Cooper Union. (That speech was instrumental in supporting Lincoln for the nomination, and then the presidency.)

Later years

In his last decade, Bryant shifted from writing his own poetry to translating Homer. He assiduously worked on translations of the Iliad and the Odyssey from 1871 to 1874. He is also remembered as one of the principal authorities on homeopathy and as a hymnist for the Unitarian Church—both legacies of his father's enormous influence on him. He was a sought-after speaker and delivered eulogies at the funerals of novelist James Fenimore Cooper and Samuel F. B. Morse, a leading figure in telegraph communications.

Bryant died in 1878, of complications from an accidental fall. In 1884, New York City's Reservoir Square, at the intersection of 42nd Street and Sixth Avenue, was renamed Bryant Park in his honor. The city later named the William Cullen Bryant High School in his honor.

Legacy

Although after his death his literary reputation declined, Bryant holds the distinction of being one of the first American poets to receive international renown.

Although he is now thought of as a New Englander, Bryant, for most of his lifetime, was thoroughly a New Yorker—and a very dedicated one at that. He was a major force behind the idea that became Central Park, as well as a leading proponent of creating the Metropolitan Museum of Art. He had close affinities with the Hudson River School of art and was an intimate friend of Thomas Cole. He defended the immigrant, and championed the rights of workers to form labor unions.

New York Medical College owes its founding, in 1860, to the vision of a group of civic leaders led by Bryant, who were particularly concerned with the condition of hospitals and medical education. They believed that medicine should be practiced with greater sensitivity to the patients. The school opened as the New York Homeopathic Medical College.[6]

It would be difficult to find a sector of the city's life that he did not work to improve.

As a writer, Bryant was an early advocate of American literary nationalism, and his own poetry focusing on nature as a metaphor for truth established a central pattern in the American literary tradition. Yet his literary reputation began to fade in the decade after the nineteenth century's midpoint, and the rise of the new poets in the twentieth century not only cast Bryant into the shadows but made him an example of all that was wrong with poetry.

A recently-published book, however, argues that a reassessment is long overdue. It finds merit in a couple of short stories Bryant wrote while trying to build interest in periodicals he edited. More importantly, it recognizes a poet of great technical sophistication who was a progenitor of Walt Whitman's poetry, to whom he was a mentor.[7]

Notes

- ↑ Homeoint.org, PHOTOTHÈQUE HOMÉOPATHIQUE. Retrieved December 10, 2007.

- ↑ "William Cullen Bryant," Business Leader Profiles for Students (Gale Research, 1999).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ homeoint.org, PHOTOTHÈQUE HOMÉOPATHIQUE. Retrieved December 10, 2007.

- ↑ William Cullen Bryant, Frank Gado, and Nicholas B. Stevens, William Cullen Bryant an American Voice (Hartford, VT: Antoca, 2006). ISBN 1584656190

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brown, Charles Henry. 1971. William Cullen Bryant. New York: Scribner. ISBN 9780684123707

- Bryant, William Cullen, Frank Gado, and Nicholas B. Stevens. 2006. William Cullen Bryant an American Voice. Hartford, VT: Antoca. ISBN 1584656190

- Muller, Gilbert H. 2008. William Cullen Bryant: Author of America. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 9780791474679

- "Willam Cullen Bryant." 1998. Encyclopedia of World Biography. Gale Research.

- "William Cullen Bryant." 1999. Business Leader Profiles for Students. Gale Research.

External links

All links retrieved October 4, 2020.

- Yarborough, Wynn. 1994. Essay on William Cullen Bryant Vcu.edu.

- Works by William Cullen Bryant. Project Gutenberg

- Selected Poems and Songs by William Cullen Bryant Angelfire.com/ks.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 06:19:19 | 3 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/William_Cullen_Bryant | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF