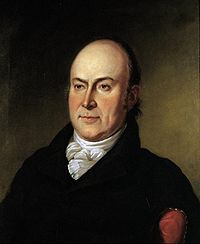

John Quincy Adams

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia | John Quincy Adams | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| 6th President of the United States From: March 4, 1825 - March 4, 1829[1] | |||

| Vice President | John C. Calhoun | ||

| Predecessor | James Monroe | ||

| Successor | Andrew Jackson | ||

| Former U.S. Representative from Massachusetts's 8th Congressional District From: March 4, 1843 – February 23, 1848 | |||

| Predecessor | William Calhoun | ||

| Successor | Horace Mann | ||

| Former U.S. Representative from Massachusetts's 12th Congressional District From: March 4, 1833 – March 4, 1843 | |||

| Predecessor | James Hodges | ||

| Successor | George Robinson | ||

| Former U.S. Representative from Massachusetts's 11th Congressional District From: March 4, 1831 – March 4, 1833 | |||

| Predecessor | Joseph Richardson | ||

| Successor | John Reed | ||

| 8th United States Secretary of State From: September 22, 1817 – March 4, 1825 | |||

| President | James Monroe | ||

| Predecessor | James Monroe | ||

| Successor | Henry Clay | ||

| Former United States Ambassador to Court of St. James's From: April 28, 1814 – September 22, 1817 | |||

| President | James Madison | ||

| Predecessor | Jonathan Russell | ||

| Successor | Richard Rush | ||

| Former United States Ambassador to Russia From: November 5, 1809 – April 28, 1814 | |||

| President | James Madison | ||

| Predecessor | William Short | ||

| Successor | James Bayard | ||

| U.S. Senator from Massachusetts From: March 4, 1803 – June 8, 1808 | |||

| Predecessor | Jonathan Mason | ||

| Successor | James Lloyd | ||

| Former United States Ambassador to Prussia From: December 5, 1797 – May 5, 1801 | |||

| President | John Adams | ||

| Predecessor | (none) | ||

| Successor | Henry Wheaton | ||

| Former United States Ambassador to the Netherlands From: November 6, 1794 – June 20, 1797 | |||

| President | George Washington | ||

| Predecessor | William Short | ||

| Successor | William Vans Murray | ||

| Information | |||

| Party | Federalist (before 1808) Republican (1808–30) National Republican (1830–1834) Anti-Masonic (1834-1838) Whig (1834 - 1848) | ||

| Spouse(s) | Louisa Catherine Johnson | ||

| Religion | Unitarianism | ||

John Quincy Adams (July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was the sixth president of the United States of America and the son of American Founding Father John Adams. He served in Congress beginning in the Jefferson Administration, one term as president (1825–1829) and then returned to Congress where he spent the remainder of his political career fighting slavery as a moral evil. He was the son of President John Adams and Abigail Adams.

A precocious teenager who aided his father in diplomatic missions, at 26 he was appointed minister[2] to the Netherlands by President George Washington, then promoted to the Berlin Legation. In 1802 Adams was elected to the US Senate and in 1808 he became the first U.S. minister of Russia. Adams served as one of the great secretaries of state under President James Monroe, arranging with Britain for the joint occupation of the Oregon Country, obtaining from Spain the cessation of the Floridas, and helping to formulate the Monroe Doctrine. He returned to Congress and became an outspoken opponent of slavery. Deeply troubled by slavery, Adams correctly predicted the dissolution of the Union on the issue, but was incorrect in predicting a series of bloody slave insurrections.

Adams presented a vision of national greatness resting on economic growth and a strong federal government, but his presidency was not a success as he lacked political adroitness, popularity or a network of supporters, and ran afoul of politicians eager to undercut him. Adams is best known as a diplomat who shaped American's foreign policy in line with his deeply conservative and ardently nationalist commitment to America's republican values. More recently he has been portrayed as the exemplar and moral leader in an era of modernization when new technologies and networks of infrastructure and communication brought to the people messages of religious revival, social reform, and party politics, as well as moving goods, money and people ever more rapidly and efficiently.[3]

Contents

Early life[edit]

Adams was born at Braintree, now Quincy, Massachusetts, on July 11, 1767. He was the son of John Adams, the second president of the United States, and Abigail Quincy Smith Adams. Abigail Adams proved to be a stern, disapproving mother while John Adams was the warmer, more loving parent. Alcoholism ruined Abigail's brothers (and later her younger son). To ensure her first-born son avoided a similar fate, she delivered a steady barrage of admonitions and criticisms to him throughout his life.[4] His father could be harsh at times, admonishing the son: "You come into life with advantages which will disgrace you if your success is mediocre. If you do not rise to the head not only of your profession, but of your country, it will be owing to your own Laziness, Slovenliness and Obstinacy."[5]

Education[edit]

Much of his early life was spent with his father on diplomatic missions, and he obtained his formal schooling piecemeal in France, Amsterdam, Leiden, and The Hague. Highly precocious, at the age of 14 Adams became secretary to Francis Dana, the American minister to Russia, and in 1783 acted as secretary to his father during the peace negotiations with Britain. When his father was appointed minister to the Court of St James (Britain) in 1785, Adams returned to Massachusetts and entered Harvard College, where he was graduated in 1787. Thereafter he studied law, was admitted to the bar in 1790, and began practicing in Boston, which bored him. He became professor of rhetoric at Harvard. In 1797 Adams married Louisa Catherine Johnson, daughter of a London-based American tobacco merchant from Maryland.

Young diplomat[edit]

When his father was sent as minister to Europe by the Continental Congress, young John Quincy Adams went with him. He remained in Europe for the next nine years. While in France he studied at the Passy Academy. Later John Adams sent his son to Leiden University, where learned both Latin and Greek. When American diplomat, Francis Dana, looked for an interpreter to travel with him to Russia, Adams, who knew Russian, volunteered. He returned to his father in Hague, Holland. Adams assisted his father, as a secretary, while his father served as American minister to several European nations. He returned to America and attended Harvard College, graduating in 1787. He then studied law. After Thomas Paine wrote an anonymous pamphlet criticizing President George Washington's policies, Adams wrote a series of anonymous articles called "Publicola", defending the president. They were so well done people assumed his father wrote them. He worked in law for two years until appointed by Washington as U.S. minister to Holland.[6]

Public service[edit]

He eventually arrived in Holland as ambassador during a time of war. The French had invaded Holland and for a time was in great danger of being exterminated. Fortunately, the French were defeated by the Dutch armies, after which he returned to America to wait for a new government to be established.

He continued his work as diplomat to Holland, until he was chosen as the minister to Portugal. But before he could leave, his father, John Adams, became president of the United States and sent his son to go as minister to Prussia, instead of Portugal. He kept the post successfully for the next four years. His father though was a very unpopular President and lost the 1800 presidential election to Thomas Jefferson. Because of this Adams returned home to his family with his wife and son, George.

U.S. politics[edit]

Returning to the United States, Adams was defeated in 1802 for the U.S. House of Representatives, but in 1803 was elected to the U.S. Senate by the Massachusetts legislature, then controlled by the Federalist Party. Like other Federalists he attacked the Louisiana Purchase as "accomplished by a flagrant violation of the Constitution." Adams soon showed that spirit of political independence which was to characterize his entire career. Crossing party lines, he supported the impeachment of Federalist judges, and, most important, Jefferson's Embargo of 1807, which was strenuously opposed by his constituents. The embargo vote alienated him completely from the Federalists, who denounced him publicly and secured his defeat in the senatorial election in June 1808. Adams then joined the Jeffersonian Republicans and was aligned with Jefferson and Madison.

Diplomat[edit]

In 1809 the new President, James Madison appointed Adams to be the minister to Russia. He remained there, even when Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Russia unsuccessfully. His career as a diplomat was immensely successful. Adams was one of five diplomats who negotiated the Treaty of Ghent with Britain; it ended the War of 1812.

Declining an appointment to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1811, he served minister to the Court of St. James (Britain).

Secretary of state[edit]

Adams appointment as secretary of state under President James Monroe in 1817 was eloquent testimony to his splendid diplomatic service as well as to his knowledge of European affairs. Few secretaries of state have been more successful. During his eight years in that office Adams succeeded in settling most of the major disputes with Britain, including questions arising over the Great Lakes, Oregon, and fishing rights. He played an important part in the purchase of Florida from Spain, restraining Monroe when the President's actions in regard to Latin America might have jeopardized the purchase. He also contributed greatly to the formulation of the Monroe Doctrine in 1823 by arguing against joint action with Britain and by suggesting that part of the doctrine which points out the differences between the political systems of the Eastern and Western Hemispheres. During the Monroe administration he was a constant advocate of nationalistic measures, Although he did not approve of slavery he supported the Missouri Compromise in 1820.

In 1818 he secured a postponement of the question of the ownership of the vast, unsettled Oregon region (which included modern British Columbia, Washington, Oregon and Idaho) by an agreement with Britain calling for a joint occupation for ten years.

Relations with Spain[edit]

After the Napoleonic wars Spain lost control of most of the American colonies. They revolted and declared independence. Rebels used American ports to equip privateers to attack Spanish ships, a practice defended by Henry Clay, who severely criticized both Monroe and Adams for their more cautious wait-and-see policy. The Floridas, still Spanish territory but with no Spanish presence to speak of, became a refuge for runaway slaves and Indian raiders. Spain was not in charge. Monroe sent in General Andrew Jackson who pushed the Seminole Indians south, executed two British merchants who were supplying weapons, deposed one governor and named another, and left an American garrison in occupation. Jackson thought he had Washington's approval, but the orders were vague. President Monroe and all his cabinet, except Adams, believed Jackson had exceeded his instructions. Secretary of War John C. Calhoun proposed to punish Jackson. Adams argued that since Spain had proved incapable of policing her territories, the United States was obliged to act in self-defense. Adams so ably justified Jackson's conduct as to silence protests either from Spain or Britain. Congress debated the question, with Clay as the leading opponent of Jackson, but it would not disapprove of what Jackson had done.

Adams negotiated the "Transcontinental Treaty" with Spain in 1819 that turned Florida over to the U.S. and resolved border issues regarding the Louisiana Purchase. The treaty recognized Spanish control of Texas (a claim taken up by Mexico when it declared independence of Spain).

The post of Secretary of State was the normal path to the White House. After 1820 Adams, intent on winning the presidency, was less successful at the State Department. He failed to make key commercial treaties because he feared the necessary American concessions would be used to attack his candidacy. Instead the nation suffered from trade wars that could have been prevented.

Rhetoric[edit]

Disowned by the Federalists and not fully accepted by the Republicans, Adams used his Boylston Professorship of Rhetoric and Oratory at Harvard as a new base.[7] Adams' devotion to classical rhetoric shaped his response to public issues. He remained inspired by classical rhetorical ideals long after the neo-classicalism and deferential politics of the founding generation had been eclipsed by the commercial ethos and mass democracy of the Jacksonian Era. Many of Adams's idiosyncratic positions were rooted in his abiding devotion to the Ciceronian ideal of the citizen-orator "speaking well" to promote the welfare of the polis.[8]

Adams was influenced by the classical republican ideal of civic eloquence espoused by British philosopher David Hume.[9] Adams adapted these classical republican ideals of public oratory to America, viewing the multilevel political structure as ripe for "the renaissance of Demosthenic eloquence." Adams's Lectures on Rhetoric and Oratory (1810) looks at the fate of ancient oratory, the necessity of liberty for it to flourish, and its importance as a unifying element for a new nation of diverse cultures and beliefs. Just as civic eloquence failed to gain popularity in Britain, in the United States interest faded in the second decade of the 18th century as the "public spheres of heated oratory" disappeared in favor of the private sphere.[10]

Politics 1820-24[edit]

The nation became more sectionalized after the economic depression of 1819 and the Missouri Compromise of 1820. This worked to Adams' advantage in the presidential election of 1824, for the old caucus system collapsed and four Republicans competed on the basis of regional strength. As the only Northeastern candidate, Adams received 84 electoral votes to 99 for Tennessee's Andrew Jackson, 41 for Georgia's William H. Crawford. and 37 for Kentucky's Henry Clay. Since no candidate had a majority, the election was thrown into the House of Representatives, which chose among the top three. Clay was out, but by opposing Jackson, he secured Adams' election on the first ballot. Adams made Clay the Secretary of State, to the outrage of Jackson who said a corrupt bargain had nullified the will of the people.

Elected president[edit]

As the election of 1824 drew near people began looking for candidates. New England voters admired Adams' patriotism and political skills and it was mainly due to their support that he entered the race. The old caucus system of the Jeffersonian Republicans had collapsed; indeed the entire First Party System had collapsed and the election was a free-for-all based on regional support. Adams had a strong base in New England. His opponents included John C. Calhoun, William Crawford, Henry Clay and the hero of New Orleans, Andrew Jackson. During the campaign Calhoun dropped out, and Crawford fell ill giving further support to the other candidates. When the election day came, Andrew Jackson won, although narrowly, the Popular and Electoral vote. However, because no candidate received a clear majority, a vote in the U.S. House of Representatives was necessary. Thanks to the support of Henry Clay, who realized he couldn't win the election, Adams held the majority of 13 states.[11]

When Adams took the Oath of Office at his Inauguration, he did not use a bible, even though he was religious. Instead, he swore the oath on a law book. According to his personal diary, he believed that since the oath was to uphold the United States Constitution and the laws of the country, the law book were appropriate.[12]

Presidency[edit]

Adams' singular intelligence, vast experience, unquestionable integrity, and devotion to his country should have made him a great chief executive. But like his father he lacked political sense and an ability to command public support, and his contentious spirit spelled defeat for him personally and for many of his policies. He proposed a comprehensive program of internal improvements (roads, ports and canals), the creation of a national university, and federal support for the arts and sciences. he favored a high tariff to encourage the building of factories, and restricted land sales to slow the movement west. Opposition from the states' rights faction quickly killed the proposals,

Even more serious was the attack by the followers of Jackson, who accused him of being a partner to a "corrupt bargain" to obtain Clay's support in the election and then appoint him secretary of state. Refusing to play politics, Adams did little or nothing to build up a personal following committed to his re-election. He refused to discharge federal officeholders when they actively joined the opposition, and even considered appointing Jackson to his cabinet. Losing control of Congress in the elections of 1826, he still persisted in his independent policies and thus insured his own overwhelming defeat by Jackson two years later. He was particularly embittered by the unfounded accusations of fraud and extravagance made against him during the campaign by his opponents (not to mention the false accusation that he pimped for the Czar.)

The Adams administration recorded no major legislative, diplomatic, military or administrative achievements. Congress did pass the high Tariff of 1828—the "tariff of abominations" that created a violent outcry especially in South Carolina. Jackson defeated Adams in a landslide in 1828, and created the modern Democrat Party and thus inaugurating the Second Party System.

One of his priorities while being the President was supporting many modernizing public projects such as military academies, universities, canals, and even an astronomical observatory. Congress always said no. Adams was President when the 50th Independence day happened, on which both John Adams and Thomas Jefferson died.

Congress again[edit]

After being defeated by Andrew Jackson in the 1828 presidential election, Adams retired in Quincy, Massachusetts. However, in 1830 he ran and won a seat in the House of Representatives as a member of the Whig Party. While many speculated that Adams ran solely to earn money, this was not the case, as he had sufficient funds to last him the rest of his life. Adams probably ran for his Congressional seat for a combination of several reasons, chief among them the fact that he tried to raise his children in the same way he was raised, which is to say they spent lots of time away from home, which had a very negative impact on one of his sons, who died untimely. Adams, a former president, may have subjected himself to the humiliation of serving as a freshman Congressman as a sort of penance.

Anti-slavery[edit]

The "Old Man Eloquent," as he was called, won renewed respect throughout the North as an opponent of slavery. Although never an abolitionist, Adams fought the extension of slavery in the territories and was derided by Southern politicians as the "hell hound of abolition". The Missouri Compromise of 1820 provoked a series of intense debates on slavery between Adams and John C. Calhoun that changed them from admiring friends into bitter enemies. Both men were brilliant students of political philosophy, and both were committed to republicanism. Both recognized the necessity of reconciling republican government with the issues of slavery and race, Adams vilified the practice of slavery as inherently corrupt and un-republican and preached total abolition. Calhoun countered that the right to slavery not only should be protected from interference from the federal government but was fundamental to republican government. The national debate led both men to consider dissolution of the Union as a way of resolving the slavery issue. Their immovable stances signaled the similar uncompromising positions adopted by the North and the South in the decades to follow.[13]

Even more spectacular was his eight-year struggle against the Southern-inspired "gag resolutions," which sought to deny the presentation and the discussion of antislavery petitions in Congress. Repeatedly threatened by irate Southerners with disbarment from Congress, he courageously kept up the struggle and finally won the right of free petition in 1844. In a dramatic statement on the floor of the House, he protested, during a vote on the gag rule, "I hold the resolution to be a direct violation of the Constitution of the United States, the rules of this House, and the rights of my constituents." Adams was known for his sharp, insightful speeches, as well as his savage attacks of his opponents. He was referred to as "the old man" just as often as "old man eloquent." His battle against the gag rule finally bore fruit as it was eventually repealed.

Missouri Compromise[edit]

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 provoked a series of intense debates between Adams and John C. Calhoun that would eventually transform them from admiring friends into bitter enemies. Both men recognized the necessity of reconciling republican government and the traditional values of the American Revolution with the issues of slavery and race. Adams vilified the practice of slavery and preached total abolition, while Calhoun countered that the right to slavery not only should be protected from interference from the federal government but was fundamental to republican government. The national debate led both men to consider dissolution of the Union as a way of resolving the slavery issue. Their immovable stances signaled the similar uncompromising positions adopted by the North and the South in the decades to follow.[14]

Amistad[edit]

In 1839 African slaves in Cuba rebelled and seized a Spanish ship Amistad. Led by Cinqué, they murdered some of their white captors and forced others to sail the ship to Africa; they sailed it instead to Connecticut, where the U.S. Navy took control. The slaves were charged with murder and with piracy; the case was complicated by salvage claims as to the ownership of the Amistad and diplomatic entanglements between the U. S. and Spain. National attention focused on the case as President Martin Van Buren wanted the slaves convicted and they were defended by Adams. Adams took the case to the Supreme Court, which held that they were free. They were returned to Africa; Christian missionaries who sponsored their return believe Cinqué became a slave trader.

Texas[edit]

In the debates over the annexation of Texas in the mid 1840s, he believed in a false conspiracy theory (popular among abolitionists) that annexation and the war with Mexico were plots hatched by southern slaveowners.

Death and legacy[edit]

He suffered a stroke on February 21, 1848 while on the House floor. He died two days later in the evening of February 23, 1848 in the capital of Washington D.C.[15]

The Adams funeral was the occasion for restoring new life into a country increasingly torn by sectional strife over slavery. The 19 days from Adams's death to his interment in the family tomb was a carefully scripted political pageantry, a dramatic expansion of American efforts to memorialize fallen leaders, and revealed a widespread intention and hope to unite the country once more around shared republican goals as expressed by the Founding Fathers.

One of his three sons, Charles Francis Adams became a distinguished American diplomat.

Regarded by contemporaries as a cold, aloof, and excessively intellectual, John Quincy Adams was deficient in personal warmth, ignored the voters and his own political supporters, was contentious, and was inclined to suspect the motives of his associates. He was also possessed of a brilliant mind, enormous energy, and abiding devotion to his country. Adams could also be cheerful and engaging, and was widely regarded to be one of his era's most brilliant dinner companions.

He kept one of the most famous diaries in American history, which was edited and partially published by his son, Charles Francis Adams, in 12 volumes, 1874–1877.

Quotes[edit]

- "The first and almost the only book deserving of universal attention is the Bible."[16]

- "Why is it that, next to the birth day of the Savior of the World, your most joyous and most venerated festival returns on this day?—And why is it that, among the swarming myriads of our population, thousands and tens of thousands among us, abstaining, under the dictate of religious principle, from the commemoration of that birth-day of Him, who brought life and immortality to light, yet unite with all their brethren of this community, year after year, in celebrating this the birthday of the nation?

- Is it not that, in the chain of human events, the birthday of the nation is indissolubly linked with the birthday of the Savior? That it forms a leading event in the progress of the gospel dispensation? Is it not that the Declaration of Independence first organized the social compact on the foundation of the Redeemer’s mission upon the earth? That it laid the cornerstone of human government upon the first precepts of Christianity, and gave to the world the first irrevocable pledge of the fulfilment of the prophecies, announced directly from Heaven at the birth of the Savior and predicted by the greatest of the Hebrew prophets six hundred years before?"[17]

- "You will never know how much it cost my generation to preserve your freedom. I hope you will make good use of it."

- "They [immigrants] must cast off the European skin, never to resume it. They must look forward to their posterity, rather than backward to their ancestors; they must be sure that whatever their own feelings may be, those of their children will cling to the prejudices of this country."[18]

- The highest glory of the American Revolution was this: it connected in one indissoluble bond the principles of civil government with the principles of Christianity.[19]

Miscellaneous Facts[edit]

- "[The Declaration of Independence] That it laid the cornerstone of human government upon the first precepts of Christianity." [20]

- The French aristocrat and American hero, the Marquis de Lafayette, gave John Quincy Adams an alligator as a pet. Adams kept it in a bathroom in the White House.

- Adams was also responsible for the first installation in the White House of a pool table. Among his more unusual hobbies, he regularly went skinny dipping in the Potomac river. The first American female professional journalist, Anne Royall, knew of Adams' habit of taking nude swims at 5 a.m. She had frequently asked for interviews with him and been refused, so she went to the river and sat on his clothes until he answered her questions, becoming the first woman to interview a president.

- Adams was the first president to have his photo taken (April 13, 1843).[21]

- He is one of two sons of presidents to be elected to the same office; the other is George W. Bush.

- He is the only ex-president to have entered the House after being President.

Further reading[edit]

- Bemis, Samuel Flagg. John Quincy Adams and the foundations of American foreign policy (1949), Pulitzer prize, vol 1

- Bemis, Samuel Flagg. John Quincy Adams and the Union (1956), Pulitzer prize, vol 2

- Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848 (2007). 928 pp. Pulitzer-prize winning survey downplays Jackson and makes Adams the hero of the entire era excerpt and text search

- Mattie, Sean. "John Quincy Adams and American Conservatism," Modern Age Volume 45, Number 4; Fall 2003 online edition

- Parsons, Lynn Hudson. John Quincy Adams. (1998). 284 pp. best short biography by scholar excerpt and text search

- Remini, Robert. John Quincy Adams (2002) short biography by leading scholar excerpt and text search

Advanced Bibliography[edit]

- Bemis, Samuel Flagg. John Quincy Adams and the foundations of American foreign policy, (1950) and John Quincy Adams and the Union (1956), classic two volume scholarly biography; Pulitzer Prize

- Cunningham, Jr., Noble E. The Presidency of James Monroe (1996)

- Dangerfield, George. The Awakening of American Nationalism: 1815 - 1828 (1954) excerpt and text search

- Gaddis, John Lewis. Surprise, Security, and the American Experience (2004) excerpt and text search

- Hargreaves, Mary W. M. The Presidency of John Quincy Adams (1985), the standard scholarly survey excerpt and text search

- Hecht, Marie B. John Quincy Adams: A Personal History of an Independent Man (1972), biography by scholar

- Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848 (2007). 928 pp. excerpt and text search

- Lewis, James E., Jr. John Quincy Adams: Policymaker for the Union. (2001). 164 pp.

- Lipsky, George A. John Quincy Adams: His Theory and Ideas (1950). online edition

- Nagel, Paul C. John Quincy Adams: A Public Life, A Private Life. (1997) 444pp; emphasis on private life and psychology; ISBN 0-679-40444-9

- Mattie, Sean. "John Quincy Adams and American Conservatism." Modern Age (2003) 45(4): 305–314. Issn: 0026-7457 Fulltext: Ebsco

- Nagel, Paul C. John Quincy Adams: A Public Life, a Private Life (1999), by a leading scholar excerpt and text search Psychohistory stressed Adams fear of failure and his manic ups and depression-filled downs

- Parsons, Lynn Hudson. John Quincy Adams. (1998). 284 pp. short introduction by scholar

- Potkay, Adam S. "Theorizing Civic Eloquence in the Early Republic: the Road from David Hume to John Quincy Adams." Early American Literature (1999) 34(2): 147–170. Issn: 0012-8163 Fulltext: Ebsco

- Rathbun, Lyon. "The Ciceronian Rhetoric of John Quincy Adams." Rhetorica (2000) 18(2): 175–215. Issn: 0734-8584

- Wood, Gary V. Heir to the Fathers: John Quincy Adams and the Spirit of Constitutional Government (2004) 356pp

Primary sources[edit]

- Adams, John Quincy. Memoirs of John Quincy Adams: Comprising Portions of His Diary from 1795 to 1848, 12 vols., edited by Charles Francis Adams (1874–77)

- vol 1 online edition

- vol 2 online edition

- vol 3 online edition

- vol 4

- vol 5 online edition

- vol 6 online edition

- vol 7 online edition

- vol 8 online edition

- vol 9 online edition

- vol 10 online edition

- vol 11 online edition

- vol 12 (1844–48) online edition

- Adams, John Quincy. The Writings of John Quincy Adams. ed. by Worthington Chauncey Ford. (1913-1917). 7 vols.

- vol 1 online edition

- vol 2 online edition

- vol 3 online edition

- vol 4 online edition

- vol 6 online edition

- vol 7 online edition

- Adams, John Quincy. Diary of John Quincy Adams [November 1779-December 1788]. Ed. David Grayson Allen et al. (1981). 2 vols.

- Adams, John Quincy. The Diary of John Quincy Adams, 1794-1845: American Political, Social and Intellectual Life from Washington to Polk ," ed, by Allan Nevins, (1929), a well-chosen selection

- LaFeber, Walter, ed. John Quincy Adams and the American Continental Empire (1965), contains Adams' letters, papers, and speeches.

References[edit]

- ↑ http://www.trivia-library.com/a/6th-us-president-john-quincy-adams.htm

- ↑ The title "ambassador" came into use much later.

- ↑ See Howe (2007).

- ↑ When her health failed and she died in 1818, Secretary of State Adams said he was too busy to return to her bedside or attend the funeral.

- ↑ Quoted in Paul C. Nagel, John Quincy Adams: A Public Life, A Private Life (1997) p. 76.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Presidents John Quincy Adams by Zachary Kent, Children's Press

- ↑ He was appointed in 1805, after turning down the presidency of Harvard.

- ↑ Lyon Rathbun, "The Ciceronian Rhetoric of John Quincy Adams." Rhetorica (2000) 18(2): 175-215.

- ↑ See David Hume, "Of Eloquence," in Essays, Political and Moral (1742)

- ↑ Adam S. Potkay, "Theorizing Civic Eloquence in the Early Republic: the Road from David Hume to John Quincy Adams." Early American Literature (1999) 34(2): 147-170.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Presidents John Quincy Adams by Zachary Kent, Children's Press

- ↑ Historical Perspectives on the Inaugural Swearing in Ceremony Donald Kennon, Ph.D., Vice President for Scholarship and Education, U.S. Capitol Historical Society, January 14, 2009, Department of the State, retrieved September 1, 2012

- ↑ Chandra Miller, "'Title Page to a Great Tragic Volume': the Impact of the Missouri Crisis on Slavery, Race, and Republicanism in the Thought of John C. Calhoun and John Quincy Adams." Missouri Historical Review (2000) 94(4): 365-388. Issn: 0026-6582

- ↑ Chandra Miller, "'Title Page to a Great Tragic Volume': the Impact of the Missouri Crisis on Slavery, Race, and Republicanism in the Thought of John C. Calhoun and John Quincy Adams." Missouri Historical Review 2000 94(4): 365-388, not online

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Presidents John Quincy Adams by Zachary Kent, Children's Press

- ↑ The Rebirth of America (1986), Arthur S. DeMoss, Pg. 37

- ↑ Speech on Independence Day, July 4th, 1837

- ↑ Immigration Into the United States

- ↑ Letter to an autograph collector from Washington on April 27, 1837, The Historical Magazine, archive.org. July 1860.

- ↑ Rediscovering God in America - Page 6, Newt Gingrich

- ↑ http://www.classroomhelp.com/lessons/Presidents/qadams.html

External links[edit]

- Essays by scholars and useful information from Miller Center at U. Virginia

- Works by John Quincy Adams - text and free audio - LibriVox

| |||||

Categories: [United States History] [Slavery] [Diplomacy] [Early National U.S.] [War of 1812] [Jacksonian Democracy] [John Adams] [Whig Party] [Islam Critics]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/19/2023 01:43:50 | 60 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/John_Quincy_Adams | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF