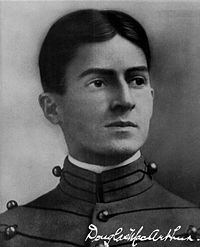

Douglas Macarthur

From Nwe

From Nwe

Douglas MacArthur (January 26, 1880 — April 5, 1964) was one of America's greatest military leaders who was instrumental in defeating the Japanese in World War II and presided over the rebuilding of Japan after the war. He also played a critical role in preventing a communist takeover of the entire Korean peninsula.

MacArthur served in the U.S. Army most of his life, participating in three major wars (World War I, World War II, Korean War) and rose to the rank of General of the Army (five-star general), a rarely held rank in American history.

One of the most decorated soldiers in United States military history, MacArthur became famous for both losing and retaking the Philippines during World War II. He was appointed Supreme Allied Commander in the Southwest Pacific Area and led a series of military victories by Allied forces in the theater. After Imperial Japan surrendered to the Allies in August 1945, MacArthur became Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers (SCAP) and rebuilt Japan from the ruins of defeat during the Allied occupation. His enlightened policy towards the Japanese and respect for their cultural traditions made him a beloved figure in that country.

In the early months of the Korean War, MacArthur led the brilliant landing of United Nations forces at Inchon that prevented North Korean forces from overrunning South Korea, and then pursued them to the Chinese border. After he advocated taking the war to China (whose forces had then intervened), a policy rejected by President Harry S. Truman, the president soon felt compelled to remove MacArthur from command on grounds of insubordination, causing a national controversy.

Douglas MacArthur remains both a controversial and larger-than-life figure in American history. Throughout his career he was often criticized for egotism. Greatly admired for his strategic and tactical brilliance, he was also criticized for his military leadership, including his command in the Philippines and New Guinea, and challenge to Truman during the Cold War. Upon his death in 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson met MacArthur's casket at Union Station in Washington, DC, and escorted it to the Capitol Rotunda where MacArthur laid in state for the nation to mourn. Johnson had ordered that General MacArthur be buried "with all the honor a grateful nation can bestow on a departed hero."[1]

Early life and education

MacArthur was born in Little Rock, Arkansas. His parents were Lieutenant General Arthur MacArthur, Jr., and Mary Pinkney Hardy MacArthur of Norfolk, Virginia. His father was a recipient of the Congressional Medal of Honor at the Battle of Missionary Ridge on November 25, 1863, during the American Civil War. In 1883, when MacArthur was three years old, his other brother Malcolm died (his older brother Arthur would later attend the United States Naval Academy and die in 1923 as a captain). MacArthur spent much of his childhood in remote parts of New Mexico, such as Fort Selden, where his father commanded an infantry company, or military unit. In his memoir Reminiscences, MacArthur wrote that his first memory was the sound of a bugle.

When MacArthur was six, his father was reassigned to Fort Leavenworth in Kansas. Three years later, the MacArthur family moved to Washington, DC when Douglas's father took a post at the United States Department of War. There he spent time with his paternal grandfather Judge Arthur MacArthur, a member of the high-profile Washington political culture that had an enormous influence on Douglas.

MacArthur's father was posted to San Antonio, Texas in 1893. There, Douglas attended the T.MI: The Episcopal School of Texas, where he became an excellent student. MacArthur entered the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1898. An outstanding cadet, he graduated as valedictorian of a class of 93 in 1903, with only two other students in the history of West Point surpassing his achievements. MacArthur became a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, where he was a leader in combat engineering. In 1898, his father fought in the Spanish-American War and in 1900, his father was appointed military governor of the Philippines, which began a long family connection to that country. His father was relieved of command for insubordination to William Howard Taft in 1901.[2] In 1905, his father was reassigned to Asia and Douglas traveled extensively with his parents, serving as military aide to his father.

In 1914, MacArthur undertook a daring reconnaissance mission in Vera Cruz, Mexico, in which he survived three groups of attackers, shooting several. For his bravery under fire and successfully completing his mission, his superior, Major General Leonard Wood, recommended him for the Congressional Medal of Honor.[3]

World War I

During World War I, MacArthur served in France with the U.S. 42nd Rainbow Division. Upon his promotion to brigadier general (the youngest ever in the Army), he became the commander of the 84th Infantry Brigade. MacArthur took his job as a soldier seriously and earned six silver stars for bravery in World War I, but he was ambivalent about war. He was not joyous about a great triumph in Essey, saying, "I saw a sight I shall never forget…. Men, women and children plodded along in mud up to their knees carrying what few household effects they could…. On other fields in other wars, how often it was to be repeated before my aching eyes."[4]

Inter-war years

In 1919, the Army Chief of Staff, General Peyton C. March, assigned MacArthur to be the superintendent of West Point. The pacifism that swept America after World War I led many to wonder whether West Point would survive. However, those who worked with MacArthur at West Point credit him with saving the institution.[5]

MacArthur made intramural athletics compulsory and introduced the playing of athletic games on Sundays, despite protest from conservatives in the surrounding area who promoted the tradition of reserving Sunday for God and family. In response, MacArthur composed the following poem, which is now etched on the portal of the West Point gymnasium:

Upon the fields of friendly strife

Are sown the seeds

That, upon other fields, on other daysWill bear the fruits of victory.

In January 1922, MacArthur announced his engagement to Louise Cromwell Brooks, a step-daughter of J. P. Morgan's partner, Edward T. Stotesbury, a divorcé with two children who had previously been dating General John J. Pershing. MacArthur proposed on their second date and she told a friend, "If he hadn't, I would have proposed to him. He was the handsomest man I had ever met.[6] They were married on February 14 at her family's villa in Palm Beach, Florida. Shortly after, MacArthur got orders transferring him to the Philippines. It is debated whether the cause of reassignment was General Pershing's revenge or traditionalists at West Point that did not like his reforms.

MacArthur had a number of inter-war period assignments, but most were in the Philippines. In the Philippines in 1930, after his first marriage ended in divorce, MacArthur established a relationship with a beautiful, sixteen-year-old Eurasian girl, Isabel Rosario Cooper. When he left for Washington, DC, a few months later to become Army Chief of Staff, he gave her a ticket to follow him on another ship. After she arrived, he put her in her own apartment, in an attempt to maintain the secrecy of the relationship.[7] MacArthur held the appointment as chief of staff to the U.S. Army until 1935. In 1932, while in Washington, DC, he commanded the troops used to disperse the Bonus Army of World War I veterans who were in the capital protesting against the government's failure to give them benefits. He was accused of using excessive force against a peaceful protest.

Prior to the inauguration of the Commonwealth of the Philippines, the man widely expected to become the first popularly-elected president of the Philippines was Manuel L. Quezon. He asked MacArthur to supervise the creation of a Philippine Army preparatory to independence. MacArthur accepted and was present at the inauguration. Legislation approved by President Franklin D. Roosevelt permitted active duty American officers to serve as military advisers overseas, and MacArthur took up residence in the Manila Hotel. Among MacArthur's assistants as military adviser to the Commonwealth of the Philippines was Dwight D. Eisenhower, later to command all Allied forces in Europe during World War II.

When MacArthur retired from the U.S. Army in 1937, he was made a field marshal of the Philippine Army by President Quezon, but returned to the Army in July 1941 as commander of United States Army Forces Far East (USAFFE), based in Manila, when he was recalled to active duty for fear of impending war with Japan.

World War II

After the United States entered World War II, MacArthur became Allied commander in the Philippines. He courted controversy on several occasions, especially when he overruled his air commander, General Lewis H. Brereton, who had requested permission to launch air attacks against Japanese bases on nearby Taiwan. Consequently, much of the U.S. Far East Air Force was destroyed on the ground in the Philippines, the prelude to the Battle of the Philippines (1941–1942). His headquarters during the period of defeat in the Philippines was in the island fortress of Corregidor, while making only one trip to the front lines in Bataan led to the disparaging moniker and ditty "Dugout Doug." In March 1942, as Japanese forces tightened their grip on the Philippines, MacArthur was ordered by President Roosevelt to relocate to Melbourne, Australia. With a select group of advisers and subordinate military commanders, MacArthur fled the Philippines, arriving at Batchelor Airfield in Australia's Northern Territory and taking The Ghan railway through the Australian outback to Adelaide. His famous speech, in which he said "I came out of Bataan and I shall return," was made at Terowie, Australia on March 20. During this period, President Manuel L. Quezon decorated him with the Philippine Distinguished Conduct Star.

MacArthur became Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) and took command of Australian, U.S., Dutch, and other Allied forces defending Australia, fighting mainly in and around New Guinea and the Dutch East Indies. On July 20, 1942, SWPA headquarters was moved to what is now the MacArthur Central Building in Brisbane, Australia, where he stayed from 1942 to 1944. Australian and American forces under MacArthur's command eventually achieved success, overrunning Japanese resistance in 1943 and 1944.

MacArthur's handling of the Australian forces under his command during this time has been the subject of much criticism, both by his contemporaries and subsequent historians.

During 1942, MacArthur controlled more Australian than U.S. forces. However, it has been claimed that he decreed that all Australian victories would be reported as "Allied victories," while American victories would be reported as American. It is also a widely-held view that, from mid-1943 on, MacArthur confined the Australian Army divisions under his command to tough and largely irrelevant actions, while reserving the more prestigious actions for his own nation's troops. As a result, there is an enduring antipathy towards MacArthur in Australia, especially concerning his attitude towards the Kokoda Track Campaign, which he thought irrelevant.

American forces under MacArthur's command took back the Philippines at the Battle of Leyte on October 20, 1944, fulfilling MacArthur's vow to return to the Philippines and consolidate their hold on the archipelago after heavy fighting. In September 1945, MacArthur received the formal Japanese surrender on the USS Missouri, which ended World War II. At the same time, he issued "General Order No. 1," which in part stated that the surrender of Japanese troops stationed on the Korean peninsula south of the 38th parallel would be received by American forces, while the surrender of Japanese north of that line would be taken by Soviet forces. This order, although formulated in August by the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington, and merely intended to be a temporary military expediency, is decried today by Koreans as the onset of the permanent division of the peninsula.

He was awarded and received the Medal of Honor for his leadership in the Southwest Pacific Theater. Philippine President Sergio Osmeña also decorated him with the Philippines' highest military award, the Medal of Valor.

Japanese Occupation

After World War II, General MacArthur served as Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP). As military governor, his responsibility was to oversee the reconstruction of Japan. MacArthur was effectively the new emperor of Japan during this period, imposing his authority on Emperor Hirohito himself. His orders from the Joint Chiefs of Staff were to establish a peaceful, democratic Japan. The July 1945 Allied Potsdam Proclamation mandated that there be freedom of speech, religion and thought, and respect for fundamental human rights in postwar Japan.[8]

MacArthur, an avid student of military history, realized democracy could not be imposed, but had to be embraced by the Japanese. He commissioned studies of Japanese culture, sociology, and psychology. But America's allies proposed more vindictive policies, especially the removal of the institution of the emperor.

MacArthur knew that destruction of the institution of the emperor would lead to civil breakdown and opposed such pressure. He realized a huge American military occupation force would be required if civil order broke down.[9] Instead, he chose to work through the emperor to proclaim freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and other civil rights necessary for democracy. MacArthur disestablished Shinto as the state religion, thus severely reducing its income. Two weeks later, on January 1, 1946, Emperor Hirohito largely renounced his divinity and affirmed his humanity in a public prescript. The price to be paid for these measures was essentially relieving Emperor Hirohito of any responsibility for war crimes committed in the past.

MacArthur invited U.S. Christian missionaries to Japan in the hopes that Christianity could make major inroads against the traditional Japanese religions of Shinto and Buddhism; he was strongly endorsed by U.S. Catholic and Protestant leaders alike, but missionary activity in Japan during the American occupation produced little result due to the entrenchment of the traditional religions.[10] MacArthur had considered converting the emperor to Christianity as a way of instituting political and cultural values more amenable to the spread of democratic institutions, but in the end, abandoned the idea fearing it would engender conflict between Protestantism and Catholicism.[11] Author and journalist John Gunther wrote that MacArthur and the Pope were the two most important people affecting religion in the world at mid-century.[12] MacArthur later remarked that he wanted to be remembered by history not for the many battles he fought, but for, in his view, "the solace and hope and faith of Christian morals" he gave Japan.

In 1946, MacArthur's staff essentially drafted the Japanese constitution in use to this day, including Article 9 (the "peace clause"), which prohibits Japan from using force to settle international disputes and from maintaining military forces (other than "self-defense" forces). The new constitution also enfranchised women and gave the right to organize labor. MacArthur also instituted land reforms, aware of the rhetoric used by Japan's left in pointing to social inequities. The 1947 Japanese Diet (national legislature) elections went smoothly and the Japanese Communist Party only won four seats. Japan became an independent state in 1952, when the San Francisco Treaty went into effect and official American occupation ended.

In its obituary of MacArthur, the New York Times noted that the "occupation of a proud nation [Japan], prostrate, bewildered and hated, was to prove a phenomenon in the history of defeat and conquest."[13]

Korean Conflict

After the surprise attack on South Korea by the North Korean army on June 25, 1950, started the Korean War, the United Nations General Assembly authorized a United Nations (UN) force to assist South Korea. MacArthur led the UN coalition counter-offensive, noted for a daring and overwhelmingly successful amphibious landing behind North Korean lines at Inchon. As his forces approached the North Korea–China border, the Chinese warned they would become involved. During his October trip to Wake Island to meet with Harry S. Truman, the president specifically asked MacArthur about the likelihood of Chinese involvement in the war. MacArthur thought it unlikely.

On October 25, 1950, Chinese People's Liberation Army "volunteers" attacked across the Yalu River, forcing UN forces to embark on a lengthy retreat. MacArthur sought armed retaliation into Chinese territory to attack depots and supply lines, but Truman refused. Truman and the State Department feared such attacks would draw China's ally and supplier, the Soviet Union, into the conflict. Angered by Truman's desire to maintain a limited war, MacArthur began issuing dire statements to the press, warning of imminent, crushing defeat.

In March 1951, after a relentless UN counterattack commanded by General Matthew B. Ridgway halted the UN's retreat, Truman alerted MacArthur of his intention to initiate cease-fire talks. Such news ended any hopes MacArthur had of enlarging the war against China, and he quickly issued his own ultimatum to China. MacArthur's declaration threatened the expansion of the war, and was similar to the recommendations the Joint Chiefs made to Truman. MacArthur received a mild rebuke. Truman apparently had enough when the Republican leader in the House read a letter from MacArthur that made public the views he had been pressing on Washington, in which he stated "There is no substitute for victory," but decided to wait for the Joint Chiefs. By early April, the Joint Chiefs determined MacArthur had to go for military reasons—they had lost confidence in his strategy.

On April 11, 1951, President Truman relieved General MacArthur of his military command, leading to a storm of controversy. Ridgway replaced MacArthur and stabilized the situation near the 38th parallel. The war continued at a stalemate for two additional years with thousands of casualties near the 38th parallel.

MacArthur's views of expanding the war in Korea to obtain the clear-cut defeat of the enemy clashed with a newly-developed concept in American war-fighting: limited war with limited aims—something MacArthur could not accept. Moreover, he determined that there was no likelihood of direct Soviet intervention in Korea if UN forces attacked China, because Stalin did not want to risk confronting the U.S. and its allies. Recently released Soviet documents indicate that Stalin preferred to let America keep bleeding in Korea, but to avoid confrontation. Yet, Truman and the Joint Chiefs feared possible Soviet use of their recently acquired atomic bomb, which MacArthur doubted. In the end, after his highly successful Inchon landing, MacArthur's subsequent serious misjudgment about the prospects of Chinese intervention then undermined his credibility at a time when a strategic decision had to be made on war aims in spring 1951. Once the armistice was signed in July 1953, UN forces merely ended hostilities, restoring the situation to approximately the status quo ante. Many South Koreans who lived through the Korean War regret MacArthur's dismissal because the division of their nation was prolonged.

While usually seen in the light of the constitutional prerogatives of the president,[14] the Truman-MacArthur controversy is occasionally viewed in a larger dimension. Former Secretary of State Alexander Haig, a young aide to MacArthur in 1950–1951, said, "Blind loyalty to a commander of a unit or even a President must be overwhelmed by one's subjective perception of the best interest of the people. And I think MacArthur was driven by that. I happen to think it's the right solution. It can be very costly to an individual."[15]

Post-dismissal

MacArthur returned to Washington in 1951 (his first time in the continental U.S. in 11 years), where he was invited to address a joint session of Congress. After being interrupted by 30 standing ovations, he concluded his speech by musing, "Old soldiers never die, they just fade away." His subsequent visit to New York was highlighted by the largest ticker-tape parade then seen.

After his relief by Truman, MacArthur initially encountered massive public adulation, which aroused expectations that he might run for president as a Republican in 1952. MacArthur himself encouraged such speculation. However, congressional hearings over Korea policy and the circumstances of MacArthur's removal contributed to a marked cooling of the public mood, and he decided not to run for the presidency.

At the 1952 Republican convention, rumors were rife that Sen. Robert Taft of Ohio offered the vice-presidential nomination to MacArthur. Taft had been the leading Republican candidate until General Dwight D. Eisenhower reversed himself and declared his candidacy just weeks earlier. Had Taft won the nomination against Eisenhower and a Taft-MacArthur ticket defeated Democratic candidate Adlai Stevenson that November, MacArthur would have become president upon Taft's sudden death in July 1953. After his election but before assuming office, Eisenhower consulted with MacArthur on Korean War strategy. Ironically, as president, Eisenhower adopted policies that were closer to MacArthur's earlier stated views than to the policies pursued by Truman.

Later years

MacArthur spent the remainder of his life quietly in New York living in a suite at the famed Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, and became chairman of the Remington Rand corporation. MacArthur nonetheless remained on active duty without assignment. From 1959, he was the nation's senior Army officer upon the death of General George C. Marshall. His one trip abroad was a 1961 "sentimental journey" to the Philippines when he was decorated by President Carlos P. Garcia with the Philippine Legion of Honor rank of Chief Commander.

Newly-elected President John F. Kennedy solicited MacArthur's counsel in 1961. The first of two meetings was shortly after the Bay of Pigs fiasco, an aborted covert invasion of Cuba. MacArthur was reportedly very critical of the Pentagon and its military advice to Kennedy. MacArthur also cautioned the young president to avoid a U.S. military build-up in Vietnam, pointing out that domestic problems should be given a much greater priority. Kennedy was said to have come out of the lengthy meeting enormously impressed. At Kennedy's later request, MacArthur successfully settled a dispute between two American amateur athletic unions as to which would have the right to select U.S. athletes for the 1964 Tokyo Summer Olympics.

General MacArthur was invited to West Point in 1962 to receive the Sylvanus Thayer Award, granted to those Americans who have performed outstanding service to the country and which former President Eisenhower himself received a year earlier. It was there where he delivered his last and famous "Duty, Honor, Country" speech.

By now MacArthur's health had begun to fail. He developed biliary cirrhosis, resulting from gallstones that had formed in his bile duct. His condition grew worse by 1964 and was advised by doctors to undergo an operation. Reluctantly, he agreed to the procedure. Unfortunately, the operation led to complications and, on April 5, 1964, Gen. Douglas MacArthur passed away, leaving an enduring legacy in the pages of American history.

MacArthur and his second wife, Tennessee-born Jean Faircloth, whom he married in 1937 (and who survived him until January 2000), are buried together in Norfolk, Virginia. Their burial site is in the rotunda of the MacArthur Memorial Building, a museum dedicated to his memory in his mother's hometown—and ironically a Navy town.

The couple's only child, Arthur MacArthur IV (b. 1938), has since changed his surname.

MacArthur's nephew and namesake, Douglas MacArthur II (1909–1997), served as U.S. ambassador to Japan from 1957 to 1961, and later as ambassador to Belgium, Austria, and Iran.

Summary of Service

West Point

- June 13, 1899 – appointed as a Cadet at the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York.

- 1900: Is the victim of hazing and becomes involved in a serious scandal where one Cadet is left dead by upperclassman abuse. Maintains his honor, and does not appear as a "snitch," by only naming cadets who hazed him who were already expelled from West Point or had previously confessed.

- June 11, 1903 – Graduates first in his class, commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers.

Early Career

- June 1903: Serves with the 3rd Battalion of Engineers in the Philippine Islands.

- 1904: Assigned to the California Debris Commission.

- April 1904: Promoted to First Lieutenant, becomes acting Chief Engineering Officer for the Army Pacific Division based in San Francisco, California.

- October 1904: Reports to Tokyo, Japan to serves as an aide to his father, Major General Arthur MacArthur, in the Far East.

- December 1906: Serves as aide-de-camp to President Theodore Roosevelt.

- August 1907: Attends the "Engineering School of Application" in Washington, DC.

- February 1908: Assigned as the Officer-in-Charge (OIC), Improvements Commission, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

- April 1908: Appointed as Commanding Officer, Company K, 3rd Battalion of Engineers. Later that year becomes an instructor at the Mounted Service School, Fort Riley, Kansas.

- April 1909: Becomes Quartermaster for the 3rd Battalion of Engineers.

- February 1911: Promoted to Captain and serves as the Officer-in-Charge of the Engineering Depot at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas.

- November 1912: Assigned to the General Staff Corps, Washington DC, for duty as a Member and Recorder of the Board of Engineering Troops.

- April 1913: Appointed as Superintendent of State, War, and Navy Buildings as a member of the General Staff.

- April 1914: Becomes the Assistant Engineering Officer of the military expedition to Veracruz, Mexico.

- December 1915: Promoted to Major, serves as an Engineering Officer on the Army General Staff.

- August 1917: Advanced to the temporary rank of Colonel in the National Army. Reports to Camp Mill, Long Island, New York to begin forming the 42nd Infantry Division.

World War I

- 1917 - 1918: Becomes Chief of Staff of the US 42nd Infantry Division and is credited with naming it the "Rainbow Division." Joins the American Expeditionary Force bound for France.

- June 1918: Appointed a Brigadier General in the National Army and serves as Divisional Chief of Staff, 84th Infantry Brigade, and is later appointed as the Divisional Commander.

- 1918 - 1919: Cited for extreme battlefield bravery and is also wounded in combat and gassed by the enemy. Was known for personally leading troops into battle, often without a weapon of his own. Begins to develop a negative relationship with General of the Armies John Pershing after feeling that Pershing is wasting the lives of his troops with bad military tactics.

- May 1919: Returns to the United States a hero but is distraught over the lack of recognition his Rainbow Division receives for actions in France.

Inter-war Years

- June 1919: Becomes the Superintendent of the US Military Academy, West Point.

- February 1920: Reverts to peacetime rank, but is one of the few officers who does not lose his World War I position. Becomes a Brigadier General in the Regular Army. Receives a negative evalution report from Pershing, now Chief of Staff, who ranks MacArthur 38 out of 45 generals and states that MacArthur has an "exalted view of himself and should remain in his present grade for several years."

- October 1922: Becomes Commanding General, District of Manila, in the Philippines.

- July 1923: While still serving as District of Manila Commander, also becomes Commander of the 23rd Infantry Brigade.

- January 1925: Promoted to Major General, becoming the youngest two-star general in the U.S. Army. Returns to the United States to become a Corps Commander.

- May 1925: Assigned as IVth Area Corps Commander, U.S. Army, encompassing areas of the state of Georgia as well as Atlanta.

- 1926 - 1927: Serves as 3rd Corps Commander, based in Baltimore, Maryland.

- 1928: Leads the US Olympic Team to Amsterdam and is then assigned as the Commanding General, Philippine Department, based in Manila.

- October 1930: Becomes the Commander of the Ninth Corps Area based in San Francisco, California.

- November 21, 1930: Appointed as a full General and becomes Chief of Staff of the United States Army.

- June 1932: Presides over the destruction of the "Bonus Army," deemed a low point of his tenure as Army Chief of Staff.

- October 1935: Completes his tour as Chief of Staff and declines retirement from the Army. Per Army regulations, reverts to his permanent rank of Major General and becomes the Office of the Military Adviser to the Commonwealth Government of the Philippines.

- December 31, 1937: Decides to retire from the United States Army. Is advanced back to the rank of General for listing on the U.S. Army retired rolls.

- 1937 - 1941: Civilian adviser to the Philippine Government on military matters. Is appointed a Field Marshal in the Philippine Army, the only American officer in history accorded with that rank. Begins wearing the cap which is so often associated with him, that being a Field Marshal cover with U.S. Army crest.

- April 1937 - marries Jean Faircloth.

- February 21, 1938 - Arthur MacArthur IV is born.

World War II

- July 26, 1941: Recalled to active service in the United States Army as a Major General.

- July 27, 1941: Appointed a Lieutenant General in the United States Army and becomes Commanding General of USAFFE (United States Army Forces in the Far East).

- December 1941: Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, is promoted to General in the Army of the United States and ordered to defend the Philippine islands from a Japanese invasion.

- February 22, 1942: President Franklin Delano Roosevelt orders MacArthur out of the Philippines as the American defense of the nation collapses. Upon leaving, MacArthur says, "I shall return."

- 1942 - 1943: Begins the conquest of New Guinea and is generally credited with halting an invasion of Australia by Japanese forces.

- 1943 - 1944: Begins a series of arguments with the Joint Chiefs of Staff regarding a return to the Philippine Islands. The majority of the Joint Chiefs want to bypass the Philippines and take Formosa. MacArthur makes a personal appeal to President Roosevelt that, should the Philippines be bypassed, he would publically denounce the war effort as betraying captured U.S. soldiers and leaving a large enemy flank to the rear of U.S. forces attacking the Japanese home islands.

- December 1944: Becomes a General of the Army and is ranked the second highest ranking officer of the U.S. Army, second only to George Marshall.

- 1944 - 1945: Due to logistics issues, the Joint Chiefs decided to invade the Philippine Islands. MacArthur again must fight to convince his superiors to invade the entire Philippine Islands, whereas initial plans call for only an invasion of the south. The Joint Chiefs at last agreed that MacArthur is to invade the Philippine Islands at Leyte Gulf and strike towards Manila.

- February 5, 1945: MacArthur fulfills his promise to return and liberates Manila.

- August 1945: Is considered for promotion to Six Star General (General of the Armies) to lead to massive invasion force which will attack Japan in 1946. Is stunned when the atomic bomb ends the war abruptly, quoted that "this apparatus will make men like me obsolete." MacArthur knew nothing of the bombs development; however, Eisenhower did.

- September, 1945: Presides over the surrender of Japan and becomes military governor of Japanese home islands. Threatens the Soviet Union with armed conflict, should Red Army soldiers attempt to occupy any part of Japan.

Occupation of Japan

- December 15, 1945 - Orders the end of Shinto as the state religion of Japan.

- 1945 - 1948: Begins sweeping reforms, drafts a new constitution for Japan, and puts an end to centuries of Emperor god-worship.

- 1948 - 1950: Becomes second man in Japan to a new Ambassador-Extraordinary, appointed by President Harry Truman. Attempts to run for President in 1948 but withdraws his candidacy after the news media states that MacArthur would be disloyal to his Commander-in-Chief if he ran against Harry Truman.

Korean War

- July 8, 1950: Following the invasion of North Korea into South Korea, MacArthur is named Commander of all United Nations forces in Korea.

- July 31, 1950: Travels to Taiwan and conducts diplomacy with Chiang Kai-Shek.

- September 15 1950: Leads UN forces at the Battle of Inchon, seen as one of the greatest military maneuvers in history.

- October 15 1950: Meets with President Truman on Wake Island after heavy disagreements develop regarding the conduct of the Korean War. When meeting Truman, it is very noticeable that MacArthur does not salute his Commander-in-Chief but rather offers a handshake.

- November - December 1950: Advocates for full scale war with China upon that nation's entry into the Korean War. Is outraged when military leaders in Washington restrict the war to only the Korean theater.

- April 11, 1951: After he publicly criticizes White House policy in Korea, Harry Truman removes MacArthur from command and orders him to return to the United States.

- April 19, 1951: At a farewell address before Congress, MacArthur gives the famous Old Soldiers Never Die speech.

- May 1951: Retires a second time from the U.S. Army, but is listed as permanently active duty due to the regulations regarding those who hold Five Star General rank. For administrative reasons, is assigned in absentee to the Office of the Army Chief of Staff.

Later life

- 1951 - 1952: Loses a great deal of public support after Senate hearings investigate into why MacArthur was relieved, and it is revealed MacArthur had advocated a full scale war with China and, if necessary, nuclear war with the Soviet Union as an escalation of the Korean conflict.

- 1952: Runs for President on the Republican platform. Loses badly in the Wisconsin Primary and withdraws from the Presidential race. Is distraught when his former aide Dwight Eisenhower secures the Republican nomination and later becomes President of the United States

- January 1955: Is nominated by the United States Congress for promotion to General of the Armies. Declines the promotion, as it would have meant a loss of retirement pay and benefits associated with being a Five Star General.

- May 12 1962 - Gives famous Duty, Honor, Country valedictory speech at West Point.

- April 5 1964: Douglas MacArthur dies at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, DC.

Dates of rank

- Second Lieutenant, United States Army: June 11, 1903

- First Lieutenant, United States Army: April 23, 1904

- Captain, United States Army: February 27, 1911

- Major, United States Army: December 11, 1915

- Colonel, National Army: August 5, 1917

- Brigadier General, National Army: June 26, 1918

- Brigadier General rank made permanent in the Regular Army: January 20, 1920

- Major General, Regular Army: January 17, 1925

- General for temporary service as Army Chief of Staff: November 21, 1930

- Reverted to permanent rank of Major General, Regular Army: October 1, 1935

- Retired in grade as a General on Regular Army rolls: December 31, 1937

- Recalled to active service as a Major General in the Regular Army: July 26, 1941

- Lieutenant General in the Army of the United States: July 27, 1941

- General, Army of the United States: December 18, 1941

- General of the Army, Army of the United States: December 18, 1944

- General of the Army rank made permanent in the Regular Army: March 23, 1946

In 1955, a bill passed by the United States Congress authorized the President of the United States to promote Douglas MacArthur to the rank of General of the Armies (a similar measure had also been proposed unsuccessfully in 1945). However, due to regulations involving retirement pay and benefits, as well as MacArthur being junior to George C. Marshall (who had not been recommended for the same promotion), MacArthur declined promotion to what many view would have been seen as a Six Star General.

Awards and decorations

During his military career, General MacArthur was awarded the following decorations from both the United States and other Allied nations. The awards listed below are those which would have been worn on a military uniform and do not include commemorative medals, unofficial decorations, and non-portable awards.

United States

- Medal of Honor

- Distinguished Service Cross (USA) with one oak leaf cluster

- Distinguished Service Medal (Army)

- Navy Distinguished Service Medal

- Distinguished Flying Cross (USA)

- Silver Star with one silver oak leaf cluster

- Bronze Star Medal with Valor device

- Purple Heart with one oak leaf cluster

- Presidential Unit Citation (USA) with 1 silver and 1 bronze oak leaf cluster

- Air Medal

- Mexican Service Medal

- World War I Victory Medal with five battle clasps

- Army of Occupation of Germany Medal

- American Defense Service Medal with “Foreign Service” clasp

- Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with two silver service stars and arrowhead device

- World War II Victory Medal

- Army of Occupation Medal with “Japan” clasp

- National Defense Service Medal

- Korean Service Medal with three bronze service stars and arrowhead device

- United Nations Service Medal

- United States Aviator Badge

- Combat Infantryman Badge

- Army General Staff Identification Badge

- Fourteen Overseas Service Bars

- Weapons Qualification Badge with Rifle and Pistol bars

Foreign awards

- Knight Grand Cross of the Military Division of the Most Honourable Order of the Bath

- French Légion d'honneur

- French Croix de Guerre

- French Medaille Militaire

- Australian Pacific Star

- Philippine Medal of Valor

- Philippine Distinguished Service Star

- Philippine Legion of Honor, Degree of Chief Commander

- Philippine Defense Medal with one service star

- Philippine Liberation Medal with four service stars

- Presidential Unit Citation (Philippines)

- Philippine Independence Medal

- Order of the Belgium Crown

- Belgian Croix de Guerre

- Belgian Order of the Cross

- Czechoslovakian Order of the White Lion

- Polish Virtuti Militari

- Polish Grand Cross of Polonia Restituta

- Grand Cross Netherlands Order of Orange-Nassau

- Yugoslavian Order of the White Eagle

- Japanese Order of the Rising Sun

- Presidential Unit Citation (Korea)

- Korean War Service Medal

- Korean Grand Cross of the Order of Military Valour and Merit

- Italian Grand Cross of the Military Order

- Italian War Cross

- Cuban Grand Cross of Military Merit

- Ecuadorian Grand Cross Order of Abdon Calderon

- Chinese Cordon of Pau Ting

- Greek Medal of Honor

- Guatemalan Cross of Military Merit

- Hungarian Grand Cross of Military Merit

- Order of Mexican Military Merit

- Grand Cross Order of Romanian Military Merit

Notes

- ↑ B. C. Mossman and M. W. Stark, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur State Funeral, 5-11 April 1964, The Last Salute: Civil and Military Funeral, 1921-1969, ch. 24. Retrieved July 5, 2007.

- ↑ William Manchester, American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur, 1880–1964 (Boston: Little Brown, 1978).

- ↑ Frazier Hunt, The Untold Story of Douglas MacArthur (New York: Devin-Adair, 1954), 52–57.

- ↑ Manchester, American Caesar, 102.

- ↑ Earl Blaik, "A Cadet Under," Assembly (Association of Graduates of U.S.M.A.) (Spring 1964): 8–11.

- ↑ Betty Beale, article in the Utica Daily Press, April 20, 1964.

- ↑ David W. Lutz, The Exercise of Military Judgment: A Philosophical Investigation of the Virtues and Vices of General Douglas MacArthur, Joint Services Conference on Professional Ethics, 1997. Retrieved June 13, 2007.

- ↑ John W. Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (New York: W.W. Norton, 1999), 74.

- ↑ Douglas MacArthur, Reminiscences (New York: Da Capo Press, 1985), 323–330.

- ↑ For a discussion of this subject, see Lawrence S. Wittner, "MacArthur and the Missionaries: God and Man in Occupied Japan," Pacific Historical Review 40, no. 1 (February 1971).

- ↑ Kyodo News International, "MacArthur considered converting emperor," Japan Policy and Politics, May 8, 2000.

- ↑ John Gunther, The Riddle of MacArthur: Japan, Korea, and the Far East (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1975).

- ↑ New York Times, "Commander of Armies That Turned Back Japan Led a Brigade in World War I," April 6, 1964.

- ↑ See for example John W. Spanier, The Truman-MacArthur Controversy and the Korean War (New York: Norton, 1965).

- ↑ Alexander Haig, Part Two: The Politics of War, The American Experience: MacArthur, enhanced transcript, PBS, 1999. Retrieved July 17, 2007.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dower, John W. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II. New York: W.W. Norton, 1999. ISBN 0393320278

- Ganoe, William Addleman. MacArthur Close-Up: Much Then and Some Now. New York: Vantage Press, 1962.

- Green, Michael. MacArthur in the Pacific: From the Philippines to the Fall of Japan. Osceola, WI: Motorbooks International, 1996. ISBN 0760302022

- Gunther, John. The Riddle of MacArthur: Japan, Korea, and the Far East. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1975. ISBN 0837177014

- Hunt, Frazier. The Untold Story of Douglas MacArthur. New York: Devin-Adair, 1954.

- James, D. Clayton. The Years of MacArthur, 3 vols. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 1975–1985. Vol. 1: ISBN 0395109485; Vol. 2: ISBN 0395204461; Vol. 3: ISBN 0395360048

- Langley, Michael. Inchon Landing: MacArthur's Last Triumph. New York: Times Books, 1980. ISBN 081290821X

- Leary, William M. MacArthur and the American Century: A Reader. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001. ISBN 0803229305

- MacArthur, Douglas. A Soldier Speaks: Public Papers and Speeches of General of the Army Douglas MacArthur. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1965.

- MacArthur, Douglas. Reminiscences. New York: Da Capo Press, 1985. ISBN 0306802546

- Manchester, William R. American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur 1880–1964. Boston: Little, Brown, 1978. ISBN 0316544981

- McCullough, David. Truman. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992. ISBN 0671869205

- Perret, Geoffrey. Old Soldiers Never Die: The Life and Legend of Douglas MacArthur. New York: Random House, 1996. ISBN 0679428828

- Rovere, Richard H., and Arthur Schlesinger. General MacArthur and President Truman: The Struggle for Control of American Foreign Policy. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1992. ISBN 1560006099

- Schaller, Michael. Douglas MacArthur: The Far Eastern General. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989. ISBN 019503886X

- Smith, Robert. MacArthur in Korea: The Naked Emperor. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1982. ISBN 0671240625

- Sodei, Rinjiro. Dear General MacArthur: Letters from the Japanese during the American Occupation. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2001. ISBN 0742511154

- Spanier, John W. The Truman-MacArthur Controversy and the Korean War. New York: Norton, 1965.

- Taaffe, Stephen. MacArthur's Jungle War: The 1944 New Guinea Campaign. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1998. ISBN 0700608702

- Valley, David J. Gaijin Shogun: General Douglas MacArthur; Stepfather of Postwar Japan. San Diego: Sektor Company, 2000. ISBN 0967817528

- Weintraub, Stanley. MacArthur's War: Korea and the Undoing of an American Hero. New York: Free Press, 2000. ISBN 0684834197

- Whitney, Courtney. MacArthur: His Rendezvous with History. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1977. ISBN 0837195640

External links

All links retrieved October 11, 2017.

- The MacArthur Memorial in Norfolk, Virginia.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 21:02:22 | 213 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Douglas_MacArthur | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF