Montana

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia | Capital | Helena |

|---|---|

| Nickname | The Treasure State (formerly "Big Sky Country") |

| Official Language | English |

| Governor | Greg Gianforte, R |

| Senator | Steve Daines, R (202) 224-2651 [1] |

| Senator | Jon Tester, D (202) 224-2644 Contact |

| Population | 1,080,000 (2020) |

| Ratification of Constitution/or statehood | November 8, 1889 (41st) |

|

Motto: "Oro y Plata" (gold and silver) |

Montana is located in the Northwestern region of the United States and on November 8, 1889, became the forty-first state to enter into the union. The capital of Montana is Helena and its largest city is Billings. The current governor of Montana is Greg Gianforte, a Republican, and its delegation to the U.S. Senate includes a Republican and a Democrat. Montana consistently votes Republican in presidential elections, and President Trump carried this state by 16 points in 2020.

The state Constitution of Montana, like all of the other 50 states, acknowledges God or our Creator or the Sovereign Ruler of the Universe. It says:

- We the people of Montana grateful to God for the quiet beauty of our state, the grandeur of our mountains, the vastness of our rolling plains, and desiring to improve the quality of life, equality of opportunity and to secure the blessings of liberty for this and future generations do ordain and establish this constitution.

Contents

Geography[edit]

The eastern 60% of the state is flat prairie and is slowly losing population, It is filled with cattle ranches, wheat farms, and oil and gas wells. The leading city is Billings, a medical and commercial center. The climate is especially harsh in the wintertime.

The western 40% is mountainous and is growing rapidly in population. Its economy is based on tourism and retirement centers, with Yellowstone National Park and Glacier National Park as prime attractions. The old copper mining industry that made Butte notorious has disappeared, and the logging industry is fading in importance. The very long border with Canada is becoming economically important, as oil from Alberta is brought by pipeline to refineries in Billings and to points as far south as Houston.

Energy[edit]

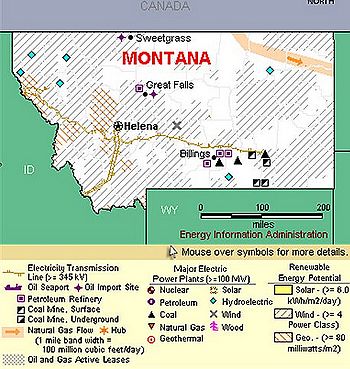

Montana is rich in fossil fuel resources and renewable energy potential. Its geologic basins hold more than one-fourth of the Nation’s estimated recoverable coal reserves. Montana’s eastern basins also hold large deposits of oil and gas. Rivers flowing from Montana’s Rocky Mountains offer substantial hydroelectric power resources. Montana contains considerable wind energy potential throughout the State.[1] Strong environmental interests (based in the western part of the state where there is little energy) have largely blocked the mining of coal and gas and are trying to stop pipelines from Canada. They instead want biofuels and wind power, which have not been profitable.The state is a leader in CO2 sequestration, and has signed agreements with Saskatchewan so that CO2 will be piped into the state and stored for thousands of years.

Montana’s population is only 1 million and so total energy demand is low. However, the State economy is energy intensive and per capita energy consumption is relatively high. The industrial sector, which includes the energy-intensive mining industry, dominates State energy consumption.

Petroleum[edit]

Montana typically accounts for roughly 2% of annual U.S. crude oil production. Production is concentrated in the Williston Basin, which covers eastern Montana and western North Dakota and contains two of the Nation’s 100 largest oil fields. Several pipelines carry Williston production south to Wyoming and east to Midwest markets. Refineries near Billings supply regional markets with petroleum products, using crude oil brought in primarily from Wyoming and Alberta, Canada. During the winter months, Montana requires oxygenated motor gasoline in the Missoula area but allows the use of conventional motor gasoline in the rest of the State.

Natural Gas[edit]

Montana produces minor quantities of natural gas. Although production is low, demand is lower, and Montana ships nearly one-half of its natural gas output to out-of-State markets. Several natural gas pipeline systems pass through the State, transporting Canadian supplies to Midwest markets. About three-fifths of Montana households use natural gas as their primary energy source for home heating.

Coal, Electricity, and Renewables[edit]

Montana's coal industry began with discoveries in the 1860s through a growth period 1900-45, a 15-year decline, and an unbroken rise since 1968. Historically, coal mining has shifted from Western to Eastern Montana, from underground to surface mining, from bituminous coal to sub-bituminous and lignite, from locomotive and smelter fuel markets to thermal generation of electric power.[2]

Today Montana typically accounts for 4% of total annual U.S. coal production. The majority of output is produced from several large surface mines in the Powder River Basin, which straddles the border between Montana and Wyoming. Just over one-fourth of Montana’s coal production is used for State electricity generation; Montana delivers the remainder to markets in more than 15 States. Minnesota and Michigan are the largest recipients of Montana coal.

Accounting for about two-thirds of State electricity generation, coal-fired power plants dominate the Montana electricity market. Hydroelectric power accounts for most of the remainder. Montana is among the leading hydroelectric power producers in the United States, and seven of the State’s 10 largest generating plants run on hydroelectric power. The State has also initiated programs to expand and enhance hydroelectric power capacity. With several operational wind farm projects in central Montana, just east of the Rockies, the State had 146 megawatts of wind power capacity at the end of 2006. High-voltage transmission lines connect Montana to other western electric power grids, allowing Montana to export large amounts of electricity to neighboring States

Water battles[edit]

Although western Montana has plenty of water, it is not always in the right place in the arid eastern half. The result has been extended controversy of state and local controls, the use of tens of thousands of private wells, the rights of Indian tribes, and the needs of oil refineries.[3] The State Engineer's Office operated 18890-1964 but unable to control water regulation and ensure dam safety. It faced varying climatic conditions, economic boom and bust, and political opposition. It never ultimately achieved the same regulatory authority of counterparts in other states. In 1965, the legislature abolished the Montana State Engineer's Office and incorporated it into the Montana Water Conservation.[4]

Montana has been fighting Wyoming for a century over control of unappropriated water in the Tongue and Powder Rivers. Both rivers originate in northeastern Wyoming and flow northward and ultimately drain into the Yellowstone River in Montana. The arguments between Wyoming and Montana water users have been contentious and of long duration. Creation of the Yellowstone River Compact Commission in 1943 failed to resolve disputes over allocation of water. In the 1970s the Montana’s Northern Cheyenne Indian tribe claimed a portion of unappropriated Tongue water, further complicating the issues. Agreements that were reached often failed to be ratified by one or the other state legislature. In 2007 the state of Montana sued Wyoming in the US Supreme Court over loss of water. After almost a century of failed compromises and continuing debate, the allocation issue remains unresolved.[5]

State government[edit]

The challenge of the 1960s was to modernize outmoded policies in state government, especially regarding prison reform, the state's budgeting and auditing procedures, public school oversight, improving state land development and investments, and the evolution of a more efficient, streamlined state government.[6]

History[edit]

Politics[edit]

In the territorial era, from 1864 until statehood in 1889, Montana Territory's 14 elections of territorial delegates to Congress show that the electorate voted for candidates they believed would have influence in Washington to gain federal support for territorial development. Martin Maginnis (1872–84), the longest tenured territorial delegate in the western territories, exemplified the delegate who could secure support in Washington for his constituents' projects. Maginnis, Joseph K. Toole (1884–88), and William H. Clagett (1871–72) were considered successful delegates because they were able to win congressional approval for additional forts, aid for railroads, and reduction of Indian reservations in Montana.[7]

Montana's political life in the 1890s was characterized by stalemate, uncompromising parochial demands, personal animosity, and corruption as local communities fought over the prizes of statehood. The major prize, the state capital, was won by Helena after a campaign featuring class and community antagonism, racist rhetoric, personal attacks, and vote buying. In the interests of local power brokers, the legislature created several units of higher education instead of establishing a consolidated university. The battles over the spoils of statehood created a pattern of cynicism and parochialism that continues to influence the state's political life.[8]

Law and order[edit]

In early 1864 in southwestern Montana some 2500 law-abiding citizens, responding to the increasing lawlessness plaguing the gold-mining towns in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, formed a vigilante society and hanged 21 villains after drumhead "trials", while warning hundreds of others to leave Montana immediately (which they did).[9]

Gangs of cattle thieves and individual rustlers threatened law and order in the late 19th century. Ranchers starting in the 1870s organized Stockmen's associations to fight back. A minority of stockmen organized into vigilante groups to protect their stock, but most stockmen worked with the legislature to create a stock commission that could oversee their interests. After 11 years of lobbying stockmen finally succeeded in getting a protective law. By working within the legislative process, stockmen transformed themselves and their frontier from a place characterized by isolation and violence to one of organization and law.[10]

Influenced by the nationwide Progressive Movement Montana cities 1890-1930 demanded police efficiency and professionalism; attempted to curb urban gambling, prostitution, and liquor use; and instilled the concept that police should serve the entire community rather than special interest groups.[11]

George Bourquin (1863-1958), as the federal judge in Montana handed down more than 250 decisions between 1912 and 1937. Ideologically conservative, Bourquin also preserved civil liberties in his decisions. Bourquin's basic faith in democracy and the Constitution, his progressivism, and his Puritan suspicion of a fundamental 'sinful behavior' helped him chart a principled and reasoned course between extreme positions. Bourquin protected the rights of labor unions and 'radicals' during World War I and the postwar Red Scare despite hostility. He also had great concern for the civil rights of Indians and attempted to protect them from government excess in cases like 'Scheer' v. 'Moody et al.,' in which he criticized the federal government's Indian policy.[12]

1894 Pullman Strike[edit]

The Pullman Strike of 1894 came in the midst of a deep depression, the Panic of 1893. It was based in Chicago but affected the entire west, especially the Northern Pacific Railroad routes in Montana. The Great Northern and Union Pacific railroads experienced less disruption. The disruptions lasted several weeks in summer 1894. Violent union activists from the newly formed American Railway Union in Billings, Livingston, Butte, Helena, and Missoula tried to stop the movement of trains operated by workers who belonged to the older established railroad brotherhoods. President Grover Cleveland, a conservative Bourbon Democrat sent in troops from the 22d US Infantry to patrol Northern Pacific. Union activists threatened and actually attacked the troops in Livingston. Unionized miners from western Montana supported A.R.U. efforts. After the strike collapsed, N.P. and U.P. officials blacklisted many Montana railroad employees. Six A.R.U. leaders were also convicted of violating an antistrike injunction. The Pullman Strike was a central event in the labor turbulence and political activism, which swept Montana during the 1890s, fostered by strong antirailroad populism among some farmers and many miners in the state.[13]

National Guard[edit]

The Montana National Guard was established in 1887. The 1st Montana Volunteer Regiment, as the Montana National Guard was known during the Spanish–American War and Philippine Insurrection. Arriving in the Philippines shortly after the Spanish surrendered in August 1898, the regiment participated in guarding Spanish prisoners of war in Cavite, securing Manila from Filipinos angry with the transfer of their country from Spain to the United States, assaulting Caloocan, and taking the provisional capital of Malolos. The performance of this and other National Guard troops in America's first overseas operation convinced the military of its value to national defense.[14]

The Montana National Guard, officially designated the 163d Regiment of the 41st Infantry Division, fought in New Guinea from December 1942 to July 1944. They also participated in the Philippines campaign. Many of the guardsmen joined the Guard in the 1930s to earn money during the Great Depression, and most never imagined being involved in the horrors of jungle combat. Disease took nearly as great a toll on the men as the Japanese did.[15]

In the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq since 2001, over 80% of the Montana Guardsmen and women have been deployed overseas at one time or another.

1889-1929[edit]

Silver mining[edit]

Silver mining began in Montana and boomed in the 1880s because of a combination of factors: geographic concentration of silver in shallow vein systems, maintenance of a subsidized silver market by the federal government, infusion of outside capital, evolution of mining and smelting technology, and railroad construction. Between 1883 and 1891, silver production in Montana ranked first or second nationwide, with the mines at Butte, Alta, and Granite as primary producers. The boom collapsed in 1893 because of depletion of the state's resources and the collapse of silver prices. Silver mining did continue, but at a reduced level. The Montana silver mining era exemplifies the common tendency for booms to develop, become overblown, and in finally collapse into extended slumps and depressions.[16]

Cattle ranching[edit]

Henry Sieben (1847-1937) came to Montana's gold fields in 1864, was a farm laborer, prospector, and freighter, then turned to livestock raising along the Smith River in 1870. In partnership with his brothers Leonard and Jacob, Henry Sieben raised cattle and became one of the territory's pioneer sheep ranchers in 1875. The partnership was dissolved in 1879 and Henry moved his stock to the Lewistown area. He established a reputation as an excellent businessman and as someone who took care of his stock and employees. After ranching in the Culbertson area, Henry Sieben purchased ranches near Cascade and along Little Prickly Pear Creek, forming the Sieben Livestock Company. By 1907, these two ranches had become the heart of his cattle and sheep raising business which he directed from his home in Helena. Sieben became well known for his business approach to ranching and for his public and private philanthropies. His family continues to operate the Sieben Ranch Company today.[17]

Flu, 1918-1919[edit]

The worldwide flu pandemic of 1918-19 killed more than 20 million people worldwide, and 675,000 Americans. Montana was one of the four hardest-hit states in the nation, as 5,000 residents, or 1% of the population, died as a result of the infection. In response to the epidemic the State Board of Health urged closing public gathering places. Such regulation spawned public resentment, but the Board of Health stood firm. Butte was the hardest hit city of Montana and one of the hardest hit in the nation. The University of Montana in Missoula closed to protect the students. In remote areas of the state isolation and limited medical personnel left many families to face illness with help from neighbors.[18]

Farming[edit]

Beginning in 1905 the Great Northern Railway in cooperation with the US Department of Agriculture, the Montana Experiment Station, and the Dryland Farming Congress promoted dryland farming in Montana in order to increase its freight traffic. During 1910-13 the Great Northern launched its own program of demonstration farms, which stimulated settlement (during 1909-10 acreage in homesteads quadrupled in Montana) through their impressive production rates for winter wheat, barley, and other grains.[19]

Wheat-raising started slowly in Montana, replacing oats as the major grain crop only in the 20th century, after development of new plant strains, techniques, and machinery. Wheat was stimulated by boom prices in World War I, but slumped in value and yield during the drought and depression of the next 20 years. The recent trend is toward increased acreage in wheat. Wheat became the major crop in eastern Montana, and the process of thrashing to remove the grain evolved over the century as machines became more specialized, faster, and more expensive. In a Montana homestead in the 1910s the work was done by humans and horses, who dealt with the separator, tumbling rod, feeder, carrier, and other parts of the equipment. By the 1930s wheat farms became increasingly dependent on larger and more sophisticated machinery and less dependent on human and animal labor. Thrashing also became an increasingly specialized activity, and farmers turned to itinerant thrashing crews to harvest their crops.[20]

Small business[edit]

Between the Civil War and World War II, small businessmen - ranchers, farmers, local merchants, mine owners, and bankers - represented the backbone of Montana's economy. Success rested upon their ability to diversify their interests into new economic activities and new products. Typical were the Isaac G. Baker Co. and the T. C. Power and Brother Co., which emphasized high-volume sales, product guarantees, and expanded merchandise lines to create statewide department stores. The Strain Brothers specialized in mail-order business and the F. A. Buttrey Co. introduced unique sales gimmicks. Likewise, John P. Barnes, Leander S. Woodbury, and A. C. Edwards demonstrated their entrepreneurial skills in mining, manufacturing and banking, respectively.[21]

Charles A. Broadwater (1840–92), a Montana pioneer, exemplified many of the characteristics embodied in the iconic "self-made man". With no profession or special skills Broadwater migrated to the Deer Lodge Valley in 1862. He traded horses, homes, and cattle. As the gold boom spread, he entered the freighting business and soon became immersed in the commercial and political life of the territory. He married into a leading Helena family and, through connections with such eastern capitalists as James J. Hill, built a business empire. He did not seek elective office, but he was a power in the territorial Democratic Party.[22]

Thomas H. Carter (1854-1911) began his public career as Montana's last territorial delegate in 1888. He served as US senator, chairman of the Republican National Committee, chairman of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition Commission, and chairman of the American sector of the International Joint Commission. He was the embodiment of the self-made man. Carter was a strong party man and firmly believed that the political process should foster economic development. He encouraged the rapid development of Western resources, and was an advocate of government irrigation. He was bypassed by the progressive Republicans at the turn of the century, who called him an old fogey.[23]

The Conrad banking business flourished in north-central and northwestern Montana during 1880-1914. Local banks at Fort Benton, Great Falls, and Kalispell, owned and managed by the William and Charles Conrad families, helped to finance Montana's economic development through an intricate pattern of familial, friendship, and business ties. Correspondent linkages to large metropolitan banks sustained the relatively small country banks by assuring them access to capital. The Conrad banks were aggressive in penetrating new lending markets and making inroads into the local farming, ranching, merchant, and manufacturing sectors. The banks grew in reputation and stature as the region developed, but remained single-unit, family-based enterprises.[24]

Towns[edit]

Boosters, led by editors and businessmen, promoted their towns by encouraging entrepreneurship and cooperation, especially through the Chamber of Commerce and clubs such as Rotary. Typical was the Helena Board of Trade, formed in 1877. It promoted Helena, transforming it from a crude mining camp to a stable, urban community—indeed, a political and economic center, with prosperity and culture. Several disastrous fires, the national financial depression of 1873, and a regional mining lull during the 1870s served as a season of trial for Helena. Such problems spurred local businessmen to take action. Among the leading proponents of unified effort was Helena Daily Herald editor Robert E. Fisk. Once formed, the Board of Trade led development of the city, including fire prevention, incorporation, and the promotion of overland and railroad transportation.[25]

Long before the malls began in the 1970s, successful businessmen built their shops and stores along the main street. in 1890-1920 many featured attractive preformed, sheet iron storefronts. Manufactured by the Mesker Brothers of St. Louis, these neoclassical, stylized facades added sophistication to brick or woodframe buildings throughout the West. Marketed by catalog, the Meskers' products sold well because of lower costs and superior service.

Christian education[edit]

To civilize the western frontier and prevent theological 'liberalism,' the Presbyterian Church sent missionaries to establish congregations and found a system of Christian schools. Reverend Sheldon Jackson superintended Presbyterian efforts in Montana. Reverend Lyman B. Crittenden and his daughter Mary began the Bozeman Female Seminary in 1873, but experienced difficulties. As a result, Crittenden moved the school, renaming it the Gallatin Valley Female Seminary. In 1878 the school closed altogether. The Presbyterian Board of Aid for Colleges and Academies opened the Bozeman Academy in 1887, but closed it in 1892 when a state supported college opened in Bozeman. In another attempt to found a permanent college, the Presbytery of Montana purchased the five year old Montana Collegiate Institute in Deer Lodge during 1882. Renamed the College of Montana, the school struggled to remain solvent until 1900. It reopened in 1904 but closed finally in 1918. Reverend Duncan M. McMillan served as president for most of the period. While low enrollments and lack of financial support plagued Presbyterian educational efforts, their work did help build a 'good' Montana on traditional Christian principals.[26]

Steamboats and Railroads[edit]

Steamboats[edit]

The late 19th century was the high point for steamboating on the upper Missouri River in Montana. Major growth came during and after the Civil War, as gold and silver were shipped out. Captain Grant Marsh opened the steamboat era on the Yellowstone River in June 1875. The military demands of the Sioux War increased traffic in 1876-77. As the Sioux were driven from the area, white settlers established towns, and Bozeman residents unsuccessfully promoted a port to rival Fort Benton. Business picked up from 1877 to 1883 as furs, buffalo hides, wool, and bullion led the way in exports. Numerous entrepreneurs and small firms were involved in the business. Traffic declined in the late 1880s as the Northern Pacific built west, and ironically, the last busy season for the steamers was 1881-82, when they carried supplies for the railroad contractors. Completion of the railroad to Billings ended commercial traffic on the Yellowstone in 1882, although there were futile efforts to maintain river traffic until 1909. While steamboats could easily compete with overland wagon freight, railroads presented a different situation. The coming of big business in the form of railroads sounded the economic death knell for steamboaters, even though one company converted to gasoline engines and lasted until the 1930s.[27]

Railroads[edit]

The Northern Pacific Railroad built a few new towns along its Yellowstone main line in Montana, as the revenue from town lots was small. The layout of the towns it did build reflected railroad influence. Billings and Livingston had a symmetrical plan centered on the railroad. In the 'T' plan at Terry, Sidney, and Townsend, the main street met the railroad at right angles. During 1900-20 the railroad built 'homestead towns,' elevator-centered communities surrounded by grain-raising homesteads. The impact of the railroad on main street plans persists.[28]

In the 1880s, Paris Gibson envisioned a town at the Great Falls of the Missouri River that would utilize power and coal available at the site to grow into an urban economic center rivaling Minneapolis. Great Northern Railroad President James J. Hill was a major investor in the project from its incorporation in 1887 until he tired of the endeavor and sold his stock in 1908. Great Falls, Montana, did become a leading city in the state, but did not realize the dreams Gibson and Hill had for it.[29]

Women[edit]

Women played a crucial role in holding together Montana farms and ranches during the first half of the 20th century. Through oral interviews many of these women are now providing a clearer picture of farm life, demonstrating that women's economic role in farm life was central, not peripheral. As managers, financiers, and laborers they contributed essential daily support to farm operations.[30]

The status of women in the 19th century trans-Mississippi West has drawn the attention of numerous interpreters, whose analyses fall into three types:

- the Frontier Thesis inspired by Frederick Jackson Turner, which argues that the West was, among other things, a liberating experience for women and men;

- the reactionists, who view the West as a place of drudgery for women, who reacted unfavorably to the isolation and the work in the West; and

- those writers who claim the West had no effect on women's lives, that it was a static, neutral frontier. The history of Montana shows that the Turner thesis best explains the improvement in women's status in Montana and the achievement of suffrage in 1914.[31]

Margery Jacoby was a typical Great Plains teacher at the turn of the 20th century. She began teaching in Montana at 15 with a first-class certificate gained by examination. She lacked formal training but attended summer school to improve her skills. She taught because her family needed the money, and she wanted independence and an opportunity to advance her own learning. The need for teachers in the West and the belief that women were natural teachers for the young also contributed to her entry. Like other Plains schoolmarms, Jacoby was a Westerner by birth and changed teaching jobs frequently. Unlike most, she was elected county superintendent of schools, served two terms, married and quit the profession. However, she never lost interest in the classroom and her daughters later became teachers.[32]

Women's clubs flourished 1890-1930, expressing the interests, needs, and beliefs of Montana women at the turn of the century. While accepting the domestic role established by the cult of true womanhood, their reformist activities reveal a persistent demand for self-expression outside the home. Homesteading was a significant experience for altering women's perceptions of their roles. They joined the men in the fields, expressed their aesthetic interests in gardens, and organized social activities. Though these clubs allowed women to fulfill their traditional roles they also encouraged women to pursue social, intellectual, and community interests.[33]

Efforts to write woman suffrage into Montana's 1889 constitution failed. Montana women, especially 'society women,' did not strongly support the suffragists. Help from national leaders and from Jeannette Rankin, who in 1916 became the nation's first congresswoman, led to success in 1914 when voters ratified a suffrage amendment passed by the legislature the previous year.[34]

Towns[edit]

In Eastern Montana, the rural towns have evolved from a large number of widely dispersed villages in 1900, through a period of expansion over the first thirty years of 20th century, to a pattern of relatively concentrated population and businesses in an urban-based economy by 2000. Mechanization, especially the rapid replacement of horses by tractors after 1945, meant one family could operate a much larger farm, so some farmers bought out their neighbors, who then moved to town along with the surplus children.

Most rural communities declined steadily in population after 1920. A few, such as Miles City, Havre, and Lewistown, grew in population, expanded their economic base, and experienced an increase in their market areas for a limited range of goods and services. These communities also became centers of employment for their own and surrounding (farm and nonfarm) population. The rural economy diversified far beyond its exclusively agricultural base, with service employment in education and medicine important, as well as small-scale factories. Interstates and paved highways, along with cell phones and internet coverage encouraged a concentration in fewer, larger centers, which drew customers and clients from a wide radius. The discovery of oil and gas along the Dakota border gave a new lease to towns such as Glendive and Sidney in region previously known for extremely brutal winter weather.

In mountainous Western Montana, as the mining camps and lumber regions faded in importance, tourism grew rapidly and many areas attracted wealthy families looking for a second home where fishing, hunting, hiking and the wildlife could be enjoyed, together with good restaurants close by. Kalispell was especially attractive, as were the college towns of Missoula and Bozeman. Red Lodge, an old coal mining town, remade its self-image and attracted tourists..

Copper[edit]

The Anaconda Copper Company, founded in 1880 and based in Butte, dominated the world copper market and poured wealth into the state for a century; it closed in the 1980s.

The 1888-1900 bitter feud between Montana copper kings Marcus Daly and William Andrews Clark played a considerable role in the economic and political life of territorial and early statehood years. It affected the mergers of large corporations, the location of the state capital, and the elections of congressional delegations. Daly's Irish Catholic (Green) heritage and Clark's Scotch-Irish Presbyterian (Orange) backgrounds were important factors in the feud.[35]

The Anaconda company fortunes began to reverse when the Chilean government expropriated all of the Anaconda's highly profitable operations in Chile between 1969 and 1971. New management took over and executed tough belt-tightening measures that did little to stop the disintegration of the company. Help appeared to arrive in 1976 in the form of a merger with the Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO), but when the Anaconda's bottom line failed to respond to ARCO's inept management, ARCO shut down the company's operations in Montana. In 1985 the company's Montana assets were sold to a local businessman. What remains today are Superfund cleanup operations run by the EPA.[36]

Journalism[edit]

The founding of the School of Journalism at the University of Montana showed the state was following national trends in the professionalization of journalism. However, the Anaconda Copper Mining Company began to dominate economic and political life in the state and, as a political strategy, purchased most of the state's daily newspapers. From the 1920s until 1959, journalists working at the newspapers could write nothing that undercut the company's business enterprises. Journalists were thus not allowed to develop and exercise their professional skills through their news judgment regarding certain business topics - lawyers and accountants made news judgments. This changed in 1959 with the purchase of the Anaconda newspapers by Lee Enterprises, a Midwestern newspaper group. Following its own traditions, Lee allowed the journalists to exercise their own editorial judgments. Don Anderson, a Montana native and Lee executive, led the way in this transformation of the state's journalists to professional status. Newspapers soon found themselves engaged in clashes with Anaconda over important issues and even taking more active roles in civic reform efforts. Lee has managed the newspapers over the years since with praise for their editorial independence but criticism of their financial frugality.

In 2005 Lee overextended itself by borrowing $1.5 billion to buy other papers, especially the biggest St. Louis newspaper. With the Recession of 2008 came drastic cutbacks in advertising revenue, and Lee is struggling to pay off its loans and is cutting staff.[37]

Elected Officials[edit]

Federal[edit]

- Sen. Steve Daines (R)

- Sen. Jon Tester (D)

- Rep. Matt Rosendale (R)

Statewide[edit]

- Governor Greg Gianforte (R)

- Lt. Governor Kristen Juras (R)

- Attorney General Tim Fox (R)

- Secretary of State Corey Stapleton (R)

- State Auditor Matt Rosendale (R)

Notable people from Montana[edit]

- Tim Babcock, Republican governor from 1962 to 1969

- Max Baucus, former Democratic U.S. Senator who formerly chaired the Senate Finance Committee

- Conrad Burns, Republican U.S. Senator from 1989 to 2007

- The Freemen, a religious cult famous for an 81-day stand off with federal agents near Jordan, Montana

- Zales Ecton, Republican U.S. Senator from 1947 to 1953; first Montana Republican to be elected by popular vote

- Evel Knievel, a famous motorcycle daredevil, was from Butte.

- Myrna Loy, an actress from the golden age of cinema. She was born in Radersville

- Mike Mansfield, leader of Democrats in Senate, 1961–77

- Donald Nutter, governor from 1961 to 1962

- Charley Pride, perhaps the most successful black country musician of all time, grew up in Helena and Great Falls

- Jeannette Rankin, a Republican from Missoula, was the very first Congresswoman in the United States

- Burton K. Wheeler, Democratic Senator; fought FDR on Court packing; isolationist

See also[edit]

Further reading[edit]

- Bevis, William W. Ten Tough Trips: Montana Writers and the West. (1990). 250 pp.

- Emmons, David M. The Butte Irish: Class and Ethnicity in an American Mining Town, 1875-1925. (1989). 443 pp.

- Farr, William E. and Toole, K. Ross. Montana: Images of the Past. (1978). 279 pp. photographs

- Hamilton, James McLellan, History of Montana: From Wilderness to Statehood (1970), older textbook; 627pp online edition

- Hargreaves, Mary W. M. Dry Farming in the Northern Great Plains: Years of Readjustment, 1920-1990. (1993). 386 pp.

- Howard, Joseph Kinsey. Montana: High, Wide and Handsome (1943), a classic narrative that challenges romanticized views of the West and calls for increased emulation of Indians who supposedly lived in harmony with the environment of the northern Great Plains. online edition

- Howard, Stanley W. Green Fields of Montana: A Brief History oof Irrigation. (1992). 153 pp.

- Karlin, Jules A. Joseph M. Dixon of Montana: Part 1, Senator and Bull Moose Manager, 1867-1917. (1974). 257 pp.

- Joseph M. Dixon of Montana. Part 2, Governor versus the Anaconda, 1917-1934. (1974). 269 pp.

- Malone, Michael P., Richard B. Roeder, and William L. Lang. Montana: A History of Two Centuries (3rd ed. 1991), standard scholarly history

- Malone, Michael P. The Battle for Butte: Mining and Politics on the Northern Frontier, 1864-1906. (1985). 281 pp.

- Newby, Rick and Hunger, Suzanne, eds. Writing Montana: Literature under the Big Sky. (Helena: Montana Center for the Book, 1996). 348 pp.

- Petrik, Paula. No Step Backward: Women and Family on the Rocky Mountain Mining Frontier, Helena, Montana, 1865-1900. (1987). 206 pp.

- Robertson, Donald B. Encyclopedia of Western Railroad History. Vol. 2: The Mountain States: Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming. (Dallas: Taylor, 1991). 418 pp.

- Rydell, Robert; Safford, Jeffrey; and Mullen, Pierce. In the People's Interest: A Centennial History of Montana State University. (1992). 324 pp.

- Searl, Molly. Montana Disasters: Fires, Floods, and Other Catastrophes. (2001). 204 pp.

- Small, Lawrence F., ed. Religion in Montana: Pathways to the Present. (1992). 380 pp.

- Smith, Duane A. Rocky Mountain West: Colorado, Wyoming, and ontana, 1859-1915. (1992). 290 pp.

- Spence, Clark C. Montana: A Bicentennial History. (1978). 211 pp. good popular history

- Spence, Clark C. Territorial Politics and Government in Montana, 1864-89. (1976). 327 pp.

- Spritzer, Donald E. Senator James E. Murray and the Limits of Post-War Liberalism. (1985). 304 pp. biography of liberal Democrat, 1940s-1970s

- Toole, K. Ross. Twentieth-Century Montana: A State of Extremes. (1972). 307 pp. by a leading historian

- VanWest, Carroll. Capitalism on the Frontier: Billings and the Yellowstone Valley in the Nineteenth Century. (1993). 281 pp. online edition

- VanWest, Carroll. A Traveler's Companion to Montana istory. (1986). 256 pp. local history and lore

- WPA. Montana: A State Guide Book (1939), very rich guide book; 444pp online edition

Primary sources[edit]

- Kittredge, William and Smith, Annick, eds. The Last Best Place: A Montana Anthology. (1988). 1161 pp.

References[edit]

Note that articles from Montana: the Magazine of Western History are online at JSTOR

- ↑ See Energy Information Administration, State Report 2009

- ↑ Robert A. Chadwick, "Coal: Montana's Prosaic Treasure." Montana: The Magazine of Western History 1973 23(4): 18-31

- ↑ Brian Shovers, "Diversions, Ditches, & District Courts: Montana's Struggle to Allocate Water" Montana: the Magazine of Western History 2005 55(1): 2-15

- ↑ James E. Sherow, "'The Fellow Who Can Talk the Loudest and Has the Best Shotgun Gets the Water': Water Regulation and the Montana State Engineer's Office, 1889-1964". Montana: the Magazine of Western History 2004 54(1): 56-69

- ↑ Hugh Lovin, A Battleground: Wyoming, Montana, and the Tongue and Powder Rivers. Lovin, Hugh.; Annals of Wyoming 2008 80(2): 2-13

- ↑ Eugene C. Tidball, "The Seminal Years of the Montana Legislative Council, 1957-1965" Montana: the Magazine of Western History 2008 58(1): 35-54, 98-99

- ↑ Richard B. Roeder, "Electing Montana's Territorial Delegates: the Beginnings of a Political System." Montana: the Magazine of Western History 1988 38(3): 58-68

- ↑ William L. Lang, "Spoils of Statehood: Montana Communities in Conflict, 1888-1894." Montana: the Magazine of Western History 1987 37(4): 34-45

- ↑ Frederick Allen, A Decent Orderly Lynching: The Montana Vigilantes (2004); Merrill G. Burlingame, "Montana's Righteous Hangmen: a Reconsideration" Montana: the Magazine of Western History 1978 28(4): 36-49

- ↑ T. A. Clay, "A Call to Order: Law, Violence, and the Development of Montana's Early Stockmen's Organizations." Montana: the Magazine of Western History 2008 58(3): 48-63, 95-96

- ↑ Robert A. Harvie, and Larry V. Bishop, "Police Reform in Montana, 1890-1918". Montana: The Magazine of Western History 1983 33(2): 46-59

- ↑ Arnon Gutfeld, "Western Justice and the Rule of Law: Bourquin on Loyalty, the 'Red Scare,' and Indians." Pacific Historical Review 1996 65(1): 85-106

- ↑ W. Thomas White, "Boycott: the Pullman Strike in Montana." Montana: the Magazine of Western History 1979 29(4): 2-13

- ↑ Richard K. Hines, "'First to Respond to Their Country's Call': the First Montana Infantry and the Spanish-American War and Philippine Insurrection, 1898-1899." Montana: the Magazine of Western History 2002 52(3): 44-57

- ↑ Carle F. O'Neil, "Pacific Memories: Montana National Guardsmen Recall the Fighting on New Guinea in World War II." Montana: the Magazine of Western History 2002 52(2): 48-57

- ↑ Robert A. Chadwick, "Montana's Silver Mining Era: Great Boom and Great Bust." Montana: The Magazine of Western History 1982 32(2): 16-31

- ↑ Dick Pace, "Henry Sieben: Pioneer Montana Stockman." Montana: the Magazine of Western History 1979 29(1): 2-15

- ↑ Pierce C. Mullen, and Michael L. Nelson, "Montanans and 'The Most Peculiar Disease': the Influenza Epidemic and Public Health, 1918-1919". Montana: the Magazine of Western History 1987 37(2): 50-61; Volney Steele, "The Flu Epidemic of 1918 on the Montana Frontier." Journal of the West 2003 42(4): 81-90

- ↑ Claire Strom, "The Great Northern Railway and Dryland Farming in Montana". Railroad History 1997 (176): 80-102

- ↑ Ralph E. Ward, "Wheat in Montana: Determined Adaptation." Montana: The Magazine of Western History 1975 25(4): 16-37; T. Eugene Barrows, "Thrashing in Montana at the Turn of the Century." Montana: the Magazine of Western History 1988 38(4): 62-66

- ↑ Henry C. Klassen, "Diversification in Montana's Small Business." Pacific Northwest Quarterly 1993 84(3): 98-107

- ↑ William E. Lang, "Charles A. Broadwater and the Main Chance in Montana." Montana: the Magazine of Western History 1989 39(3): 30-36

- ↑ Richard B. Roeder, "Thomas H. Carter, Spokesman for Western Development." Montana: the Magazine of Western History 1989 39(2): 23-29

- ↑ Henry C. Klassen, The Early Growth of the Conrad Banking Enterprise in Montana, 1880-1914. Great Plains Quarterly 1997 17(1): 49-62

- ↑ Joan Bishop, "A Season of Trial: Helena's Entrepeneurs Nurture a City." Montana: The Magazine of Western History 1978 28(3): 62-71

- ↑ Norman J. Bender, "The Very Atmosphere Is Charged with Unbelief: Presbyterians and Higher Education in Montana, 1869-1900." Montana: the Magazine of Western History 1978 28(2): 16-25

- ↑ William E. Lass, "Missouri River Steamboating." North Dakota History 1989 56(3): 3-15; William E. Lass, "Steamboats on the Yellowstone." Montana: the Magazine of Western History 1985 35(4): 26-41

- ↑ John C. Hudson, "Main Streets of the Yellowstone Valley." Montana: the Magazine of Western History 1985 35(4): 56-67

- ↑ W. Thomas White, "Paris Gibson, James J. Hill and the 'New Minneapolis': the Great Falls Water Power and Townsite Company, 1882-1908." Montana: the Magazine of Western History 1983 33(3): 60-69

- ↑ Laurie K Mercier, "Women's Role in Montana Agriculture: 'You Had to Make Every Minute Count'". Montana: the Magazine of Western History 1988 38(4): 50-61

- ↑ Judith K. Cole, "A Wide Field for Usefulness: Women's Civil Status and the Evolution of Women's Suffrage on the Montana Frontier, 1864-1914". American Journal of Legal History 1990 34(3): 262-294

- ↑ Kathleen Underwood, "Schoolmarms on the Upper Missouri." Great Plains Quarterly 1991 11(4): 225-233

- ↑ Stephenie Ambrose Tubbs, "Montana Women's Clubs at the Turn of the Century." Montana: The Magazine of Western History 1986 36(1): 26-35

- ↑ T.A. Larson, "Montana Women and the Battle of the Ballot." Montana: The Magazine of Western History 1973 23(1): 24-41

- ↑ David Emmons, "The Orange and the Green in Montana: a Reconsideration of the Clark-Daly Feud." Arizona & the West 1986 28(3): 225-245

- ↑ Eugene C. Tidball, "What Ever Happened to the Anaconda Company?" Montana: the Magazine of Western History' 1997 47(2): 60-68

- ↑ John T. McNay, "Breaking the Copper Collar: Press Freedom, Professionalization and the History of Montana Journalism." American Journalism 2008 25(1): 99-123

| |||||

Categories: [Montana] [Rocky Mountains] [Great Plains] [Plains of the United States] [States of the United States] [Western United States] [Red States]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/24/2023 20:48:09 | 309 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Montana | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF