Ship Of The Line

From Handwiki

From Handwiki

thumb|right|HMS Hercule as depicted in her fight against the frigate Poursuivante

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which involved the two columns of opposing warships maneuvering to volley fire with the cannons along their broadsides. In conflicts where opposing ships were both able to fire from their broadsides, the opponent with more cannons firing – and therefore more firepower – typically had an advantage.

From the end of the 1840s, the introduction of steam power brought less dependence on the wind in battle and led to the construction of screw-driven wooden-hulled ships of the line; a number of purely sail-powered ships were converted to this propulsion mechanism. However, the rise of the ironclad frigate, starting in 1859, made steam-assisted ships of the line obsolete. The ironclad warship became the ancestor of the 20th-century battleship, whose very designation is itself a contraction of the phrase "ship of the line of battle" or, more colloquially, "battleship of the line".

The term "ship of the line" has fallen into disuse except in historical contexts, after warships and naval tactics evolved and changed from the mid-19th century, at least in English (the Imperial German Navy called its battleships Linienschiffe until World War I[1]).

History

Predecessors

The heavily armed carrack, first developed in Portugal for either trade or war in the Atlantic Ocean, was the precursor of the ship of the line. Other maritime European states quickly adopted it in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. These vessels were developed by fusing aspects of the cog of the North Sea and galley of the Mediterranean Sea. The cogs, which traded in the North Sea, in the Baltic Sea and along the Atlantic coasts, had an advantage over galleys in battle because they had raised platforms called "castles" at bow and stern that archers could occupy to fire down on enemy ships or even to drop heavy weights from. At the bow, for instance, the castle was called the forecastle (usually contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le, and pronounced FOHK-səl). Over time these castles became higher and larger, and eventually were built into the structure of the ship, increasing overall strength. This aspect of the cog remained in the newer-style carrack designs and proved its worth in battles like that at Diu in 1509.

The Mary Rose was an early 16th-century England carrack or "great ship". She was heavily armed with 78 guns and 91 after an upgrade in the 1530s. Built in Portsmouth in 1510–1512, she was one of the earliest purpose-built men-of-war in the English navy. She was over 500 tons burthen and had a keel of over 32 metres (105 ft) and a crew of over 200 sailors, composed of 185 soldiers and 30 gunners. Although the pride of the English fleet, she accidentally sank during the Battle of the Solent, 19 July 1545.

Henri Grâce à Dieu (English: "Henry Grace of God"), nicknamed "Great Harry", was another early English carrack. Contemporary with Mary Rose, Henri Grâce à Dieu was 50 metres (160 ft) long, measuring 1,000–1,500 tons burthen and having a complement of 700–1,000. It is said[by whom?] that she was ordered by Henry VIII in response to the Scottish ship Michael, launched in 1511. She was originally built at Woolwich Dockyard from 1512 to 1514 and was one of the first vessels to feature gunports and had twenty of the new heavy bronze cannon, allowing for a broadside. In all, she mounted 43 heavy guns and 141 light guns. She was the first English two-decker, and when launched she was the largest and most powerful warship in Europe, but she saw little action. She was present at the Battle of the Solent against Francis I of France in 1545 (in which Mary Rose sank) but appears to have been more of a diplomatic vessel, sailing on occasion with sails of gold cloth. Indeed, the great ships were almost as well known for their ornamental design (some ships, like the Vasa, were gilded on their stern scrollwork) as they were for the power they possessed.

Carracks fitted for war carried large-calibre guns aboard. Because of their higher freeboard and greater load-bearing ability, this type of vessel was better suited than the galley to wield gunpowder weapons. Because of their development for conditions in the Atlantic, these ships were more weatherly than galleys and better suited to open waters. The lack of oars meant that large crews were unnecessary, making long journeys more feasible. Their disadvantage was that they were entirely reliant on the wind for mobility. Galleys could still overwhelm great ships, especially when there was little wind and they had a numerical advantage, but as great ships increased in size, galleys became less and less useful.

Another detriment was the high forecastle, which interfered with the sailing qualities of the ship; the bow would be forced low into the water while sailing before the wind. But as guns were introduced and gunfire replaced boarding as the primary means of naval combat during the 16th century, the medieval forecastle was no longer needed, and later ships such as the galleon had only a low, one-deck-high forecastle. By the time of the 1637 launching of England's Sovereign of the Seas, the forecastle had disappeared altogether.

During the 16th century the galleon evolved from the carrack. It was a longer and more manoeuvrable type of ship with all the advantages of the carrack. The main ships of the English and Spanish fleets in the Battle of Gravelines of 1588 were galleons; all of the English and most of the Spanish galleons survived the battle and the following storm even though the Spanish galleons suffered the heaviest attacks from the English while regrouping their scattered fleet. By the 17th century every major European naval power was building ships like these.

With the growing importance of colonies and exploration and the need to maintain trade routes across stormy oceans, galleys and galleasses (a larger, higher type of galley with side-mounted guns, but lower than a galleon) were used less and less, and only in ever more restricted purposes and areas, so that by about 1750, with a few notable exceptions, they were of little use in naval battles.

Line-of-battle adoption

.jpg)

King Erik XIV of Sweden initiated construction of the ship Mars in 1563; this might have been the first attempt of this battle tactic, roughly 50 years ahead of widespread adoption of the line of battle strategy.[citation needed] Mars was likely the largest ship in the world at the time of her build, equipped with 107 guns at a full-length of 96 metres (315 ft).[citation needed] Ironically it became the first ship to be sunk by gunfire from other ships in a naval battle.[citation needed]

In the early to mid-17th century, several navies, particularly those of the Netherlands and England, began to use new fighting techniques. Previously battles had usually been fought by great fleets of ships closing with each other and fighting in whatever arrangement they found themselves in, often boarding enemy vessels as opportunities presented themselves. As the use of broadsides (coordinated fire by the battery of cannon on one side of a warship) became increasingly dominant in battle, tactics changed. The evolving line-of-battle tactic, first used in an ad hoc way, required ships to form single-file lines and close with the enemy fleet on the same tack, battering the enemy fleet until one side had had enough and retreated. Any manoeuvres would be carried out with the ships remaining in line for mutual protection.

In order that this order of battle, this long thin line of guns, may not be injured or broken at some point weaker than the rest, there is at the same time felt the necessity of putting in it only ships which, if not of equal force, have at least equally strong sides. Logically it follows, at the same moment in which the line ahead became definitively the order for battle, there was established the distinction between the ships 'of the line', alone destined for a place therein, and the lighter ships meant for other uses.[2]

The lighter ships were used for various functions, including acting as scouts, and relaying signals between the flagship and the rest of the fleet. This was necessary because from the flagship, only a small part of the line would be in clear sight.

The adoption of line-of-battle tactics had consequences for ship design. The height advantage given by the castles fore and aft was reduced, now that hand-to-hand combat was less essential. The need to manoeuvre in battle made the top weight of the castles more of a disadvantage. So they shrank, making the ship of the line lighter and more manoeuvrable than its forebears for the same combat power. As an added consequence, the hull itself grew larger, allowing the size and number of guns to increase as well.

Evolution of design

In the 17th century fleets could consist of almost a hundred ships of various sizes, but by the middle of the 18th century, ship-of-the-line design had settled on a few standard types: older two-deckers (i.e., with two complete decks of guns firing through side ports) of 50 guns (which were too weak for the battle line but could be used to escort convoys), two-deckers of between 64 and 90 guns that formed the main part of the fleet, and larger three- or even four-deckers with 98 to 140 guns that served as admirals' command ships. Fleets consisting of perhaps 10 to 25 of these ships, with their attendant supply ships and scouting and messenger frigates, kept control of the sea lanes for major European naval powers whilst restricting the sea-borne trade of enemies.

The most common size of sail ship of the line was the "74" (named for its 74 guns), originally developed by France in the 1730s, and later adopted by all battleship navies. Until this time the British had 6 sizes of ship of the line, and they found that their smaller 50- and 60-gun ships were becoming too small for the battle line, while their 80s and over were three-deckers and therefore unwieldy and unstable in heavy seas. Their best were 70-gun three-deckers of about 46 metres (151 ft) long on the gundeck, while the new French 74s were around 52 metres (171 ft). In 1747 the British captured a few of these French ships during the War of Austrian Succession. In the next decade Thomas Slade (Surveyor of the Navy from 1755, along with co-Surveyor William Bately) broke away from the past and designed several new classes of 51-to-52-metre (167 to 171 ft) 74s to compete with these French designs, starting with the Dublin and Bellona classes. Their successors gradually improved handling and size through the 1780s.[3] Other navies ended up building 74s also as they had the right balance between offensive power, cost, and manoeuvrability. Eventually around half of Britain's ships of the line were 74s. Larger vessels were still built, as command ships, but they were more useful only if they could definitely get close to an enemy, rather than in a battle involving chasing or manoeuvring. The 74 remained the favoured ship until 1811, when Seppings's method of construction enabled bigger ships to be built with more stability.

In a few ships the design was altered long after the ship was launched and in service. In the Royal Navy, smaller two-deck 74- or 64-gun ships of the line that could not be used safely in fleet actions had their upper decks removed (or razeed), resulting in a very stout, single-gun-deck warship called a razee. The resulting razeed ship could be classed as a frigate and was still much stronger. The most successful razeed ship in the Royal Navy was HMS Indefatigable, commanded by Sir Edward Pellew.

The Spanish ship Nuestra Señora de la Santísima Trinidad, was a Spanish first-rate ship of the line with 112 guns. This was increased in 1795–96 to 130 guns by closing in the spar deck between the quarterdeck and forecastle, and around 1802 to 140 guns, thus creating what was in effect a continuous fourth gundeck although the extra guns added were actually relatively small. She was the heaviest-armed ship in the world when rebuilt, and bore the most guns of any ship of the line outfitted in the Age of Sail.

Mahmudiye (1829), ordered by the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II and built by the Imperial Naval Arsenal on the Golden Horn in Istanbul, was for many years the largest warship in the world. The 76.15 m × 21.22 m (249.8 ft × 69.6 ft)[Note 1] ship of the line was armed with 128 cannons on three decks and was manned by 1,280 sailors. She participated in the Siege of Sevastopol (1854–1855) during the Crimean War (1854–1856). She was decommissioned in 1874.

The second largest sailing three-decker ship of the line ever built in the West and the biggest French ship of the line was the Valmy, launched in 1847. She had vertical sides, which increased significantly the space available for upper batteries, but reduced the stability of the ship; wooden stabilisers were added under the waterline to address the issue. Valmy was thought to be the largest sort of sailing ship possible, as larger dimensions made the manoeuvre of riggings impractical with mere manpower. She participated in the Crimean War, and after her return to France later housed the French Naval Academy under the name Borda from 1864 to 1890.

HMS Victory at drydock in Portsmouth Harbour, 2007

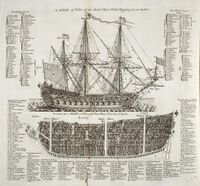

A contemporary diagram illustrating a first- and a third-rate ship

Mahmudiye (1829)

Valmy (1847)

Weight growth of RN first-rate ships of the line 1630–1861, including for comparison large early ironclads. Note the way steam allowed an increase in the rate of growth.

Steam power

The first major change to the ship-of-the-line concept was the introduction of steam power as an auxiliary propulsion system. The first military uses of steamships came in the 1810s, and in the 1820s a number of navies experimented with paddle steamer warships. Their use spread in the 1830s, with paddle-steamer warships participating in conflicts like the First Opium War alongside ships of the line and frigates.[4]

Paddle steamers, however, had major disadvantages. The paddle wheel above the waterline was exposed to enemy fire, while itself preventing the ship from firing broadsides effectively. During the 1840s, the screw propeller emerged as the most likely method of steam propulsion, with both Britain and the US launching screw-propelled warships in 1843. Through the 1840s, the British and French navies launched ever larger and more powerful screw ships, alongside sail-powered ships of the line. In 1845, Viscount Palmerston gave an indication of the role of the new steamships in tense Anglo-French relations, describing the English Channel as a "steam bridge", rather than a barrier to French invasion. It was partly because of the fear of war with France that the Royal Navy converted several old 74-gun ships of the line into 60-gun steam-powered blockships (following the model of Fulton's Demologos), starting in 1845.[4] The blockships were "originally conceived as steam batteries solely for harbour defence, but in September 1845 they were given a reduced [sailing] rig rather than none at all, to make them sea-going ships.… The blockships were to be a cost-effective experiment of great value."[5] They subsequently gave good service in the Crimean War.

.jpg)

The French Navy, however, developed the first purpose-built steam battleship with the 90-gun Napoléon in 1850.[6] She is also considered the first true steam battleship, and the first screw battleship ever.[7] Napoléon was armed as a conventional ship of the line, but her steam engines could give her a speed of 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph), regardless of the wind conditions – a potentially decisive advantage in a naval engagement.

Eight sister ships to Napoléon were built in France over a period of ten years, but the United Kingdom soon took the lead in production, in number of both purpose-built and converted units. Altogether, France built 10 new wooden steam battleships and converted 28 from older battleship units, while the United Kingdom built 18 and converted 41.[8]

In the end, France and Britain were the only two countries to develop fleets of wooden steam screw battleships, although several other navies made some use of a mixture of screw battleships and paddle-steamer frigates. These included Russia, Turkey, Sweden, Naples, Prussia, Denmark , and Austria.[4]

Decline

In the Crimean War, six line-of-battle ships and two frigates of the Russian Black Sea Fleet destroyed seven Ottoman frigates and three corvettes with explosive shells at the Battle of Sinop in 1853.[9]

In the 1860s unarmoured steam line-of-battle ships were replaced by ironclad warships. In the American Civil War, on March 8, 1862, during the first day of the Battle of Hampton Roads, two unarmoured Union wooden frigates were sunk and destroyed by the Confederate ironclad CSS Virginia.

However, the power implied by the ship of the line would find its way into the ironclad, which would develop during the next few decades into the concept of the battleship.

Several navies still use terms equivalent to the "ship of the line" for battleships, including the German (Linienschiff) and Russian (lineyniy korabl` (лине́йный кора́бль) or linkor (линкор) in short) navies.

Combat

In the North Sea and Atlantic Ocean, the fleets of the Royal Navy, the Netherlands, France, Spain and Portugal fought numerous battles. In the Baltic, the Scandinavian kingdoms and Russia did likewise, while in the Mediterranean Sea, the Ottoman Empire, Spain, France, Britain and the various Barbary pirates battled.

By the eighteenth century, the UK had established itself as the world's preeminent naval power. Attempts by Napoleon to challenge the Royal Navy's dominance at sea proved a colossal failure. During the Napoleonic Wars, Britain defeated French and allied fleets decisively all over the world including in the Caribbean at the Battle of Cape St. Vincent, the Bay of Aboukir off the Egyptian coast at the Battle of the Nile in 1798, near Spain at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, and in the second Battle of Copenhagen (1807). The UK emerged from the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 with the largest and most professional navy in the world, composed of hundreds of wooden, sail-powered ships of all sizes and classes.

Overwhelming firepower was of no use if it could not be brought to bear which was not always possible against the smaller leaner ships used by Napoleon's privateers, operating from French New World territories. The Royal Navy compensated by deploying numerous Bermuda sloops. Similarly, many of the East India Company's merchant vessels became lightly armed and quite competent in combat during this period, operating a convoy system under an armed merchantman, instead of depending on small numbers of more heavily armed ships which while effective, slowed the flow of commerce.

Restorations and preservation

The only original ship of the line remaining today is HMS Victory, preserved as a museum in Portsmouth to appear as she was while under Admiral Horatio Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. Although Victory has been in dry dock since the 1920s, she is still a fully commissioned warship in the Royal Navy and is the oldest commissioned warship in any navy worldwide.[10]

Regalskeppet Vasa sank in lake Mälaren in 1628 and was lost until 1956. She was then raised intact, in remarkably good condition, in 1961 and is presently on display at the Vasa Museum in Stockholm, Sweden. At the time she was the largest Swedish warship ever built.[11] Today the Vasa Museum is the most visited museum in Sweden.[citation needed]

The last ship-of-the-line afloat was the French ship Duguay-Trouin, renamed HMS Implacable after being captured by the British, which survived until 1949. The last ship-of-the-line to be sunk by enemy action was HMS Wellesley, which was sunk by an air raid in 1940, during the Second World War; she was briefly re-floated in 1948 before being broken up.

List

- List of ships of the line of Denmark

- List of ships of the line of the Dutch Republic

- List of ships of the line of France

- List of ships of the line of Spain

- List of ships of the line of Italy

- List of ships of the line of Malta

- List of ships of the line of the Ottoman Empire

- List of ships of the line of Russia

- List of ships of the line of the Royal Swedish Navy

- List of ships of the line of the Royal Navy

- List of ships of the line of the United States Navy

See also

- List of battleships by country

- Man-of-war

Notes

- ↑ The vessel was 201 kadem in length and 56 kadem in beam. One kadem measures 37.887 centimetres (1.2 ft). Kadem (which translates as "foot") is often misinterpreted as equivalent in length to one imperial foot, hence the wrongly converted dimensions of "201×56 ft, or 62×17 m" in some sources.

References

- ↑ Jochen Brennecke, Herbert Hader, "Panzerschiffe und Linienschiffe", 1860–1910, Köhlers Verlagsgesellschaft, Herford 1976, ISBN:3-78220-116-7

- ↑ Mahan, A. T., The Influence of Sea Power Upon History 1660–1783, p. 116, quoting Chabaud-Arnault

- ↑ Angus Constam & Tony Bryan (2001). British Napoleonic Ship-of-the-Line. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-308-X. as seen on books.google.com Konstam, Angus (25 November 2001). British Napoleonic Ship-of-the-Line – Google Book Search. ISBN 9781841763088. https://books.google.com/books?id=Og_73Qn8jp8C&q=William+Bately&pg=PT5. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Sondhaus, L. Naval Warfare, 1815–1914

- ↑ p. 30, Lambert, Andrew. Battleships in Transition, the Creation of the Steam Battlefleet 1815–1860, Conway Maritime Press, 1984. ISBN:0-85177-315-X.

- ↑ "Napoleon (90 guns), the first purpose-designed screw line of battleships", Steam, Steel and Shellfire, Conway's History of the Ship, p. 39.

- ↑ "Hastened to completion Le Napoleon was launched on 16 May 1850, to become the world's first true steam battleship", Steam, Steel and Shellfire, Conway's History of the Ship, p. 39.

- ↑ Steam, Steel and Shellfire, Conway's History of the Ship, p. 41.

- ↑ Lambert, Andrew D, The Crimean War, British Grand Strategy Against Russia, 1853–56, pub Manchester University Press, 1990, ISBN:0-7190-3564-3, pages 60–61.

- ↑ Smith, Emily (5 December 2011). "HMS Victory: World's oldest warship to get $25m facelift". CNN.com (Turner Broadcasting System, Inc.). http://edition.cnn.com/2011/12/05/world/europe/hms-victory.

- ↑ Magazine, Smithsonian; Eschner, Kat. "The Bizarre Story of 'Vasa,' the Ship That Keeps On Giving" (in en). https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/bizarre-story-vasa-ship-keeps-giving-180964328/.

Bibliography

External links

- The evolution of the ship of the line.

- Michael Philips, Notes on Sailing Warships, 2000.

- Ship of the Line from battleships-cruisers.co.uk History of the Ship of the Line of the Royal Navy]

- Reconstruction of Ship of the Line 'Delft' (1783–1797). Rotterdam (Delfshaven) The Netherlands

|

Categories: [Ships of the line] [Naval sailing ship types]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 07/31/2024 14:39:19 | 17 views

☰ Source: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Engineering:Ship_of_the_line | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

KSF

KSF