Canes Venatici

From Handwiki

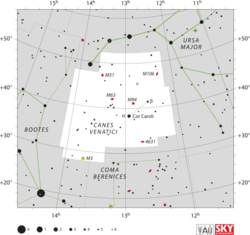

From Handwiki | Constellation | |

List of stars in Canes Venatici | |

| Abbreviation | CVn |

|---|---|

| Genitive | Canum Venaticorum |

| Pronunciation | /ˈkeɪniːz vɪˈnætɪsaɪ/ KAY-neez vih-NAT-ih-seye,[1] genitive /ˈkeɪnəm vɪnætɪˈkɒrəm/ |

| Symbolism | the Hunting Dogs |

| Right ascension | 12h 06.2m to 14h 07.3m |

| Declination | +27.84° to +52.36°[2] |

| Area | 465 sq. deg. (38th) |

| Main stars | 2 |

| Bayer/Flamsteed stars | 21 |

| Stars with planets | 4 |

| Stars brighter than 3.00m | 1 |

| Stars within 10.00 pc (32.62 ly) | 2 |

| Brightest star | Cor Caroli (Asterion) (α CVn) (2.90m) |

| Messier objects | 5 |

| Meteor showers | Canes Venaticids |

| Bordering constellations |

|

| Visible at latitudes between +90° and −40°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of May. | |

Canes Venatici (/ˈkeɪniːz vɪˈnætɪsaɪ/) is one of the 88 constellations designated by the International Astronomical Union (IAU). It is a small northern constellation that was created by Johannes Hevelius in the 17th century. Its name is Latin for 'hunting dogs', and the constellation is often depicted in illustrations as representing the dogs of Boötes the Herdsman, a neighboring constellation.

Cor Caroli is the constellation's brightest star, with an apparent magnitude of 2.9. La Superba (Y CVn) is one of the reddest naked-eye stars and one of the brightest carbon stars. The Whirlpool Galaxy is a spiral galaxy tilted face-on to observers on Earth, and was the first galaxy whose spiral nature was discerned. In addition, quasar Ton 618 is one of the most massive black holes with the mass of 66 billion solar masses.

History

The stars of Canes Venatici are not bright. In classical times, they were listed by Ptolemy as unfigured stars below the constellation Ursa Major in his star catalogue.

In medieval times, the identification of these stars with the dogs of Boötes arose through a mistranslation: some of Boötes's stars were traditionally described as representing the club (Greek: κολλοροβος, kollorobos) of Boötes. When the Greek astronomer Ptolemy's Almagest was translated from Greek to Arabic, the translator Hunayn ibn Ishaq did not know the Greek word and rendered it as a similar-sounding compound Arabic word for a kind of weapon, writing العصا ذات الكُلاب al-'aşā dhāt al-kullāb, which means 'the staff having a hook'.

When the Arabic text was later translated into Latin, the translator, Gerard of Cremona, mistook كُلاب kullāb ('hook') for كِلاب kilāb ('dogs'). Both written words look the same in Arabic text without diacritics, leading Gerard to write it as Hastile habens canes ('spearshaft-having dogs').[3] In 1533, the German astronomer Peter Apian depicted Boötes as having two dogs with him.[4]

These spurious dogs floated about the astronomical literature until Hevelius decided to make them a separate constellation in 1687.[5] Hevelius chose the name Asterion[lower-alpha 1] for the northern dog and Chara[lower-alpha 2] for the southern dog, as Canes Venatici, 'the hunting dogs', in his star atlas.[7]

In his star catalogue, the Czech astronomer Antonín Bečvář assigned the names Asterion to β CVn and Chara to α CVn.[8]

Although the International Astronomical Union dropped several constellations in 1930 that were medieval and Renaissance innovations, Canes Venatici survived to become one of the 88 IAU designated constellations.[9]

Neighbors and borders

Canes Venatici is bordered by Ursa Major to the north and west, Coma Berenices to the south, and Boötes to the east. The three-letter abbreviation for the constellation, as adopted by the International Astronomical Union in 1922, is "CVn".[10] The official constellation boundaries, as set by Belgian astronomer Eugène Delporte in 1930,[9] are defined by a polygon of 14 sides.

In the equatorial coordinate system, the right ascension coordinates of these borders lie between 12h 06.2m and 14h 07.3m, while the declination coordinates are between +27.84° and +52.36°.[2] Covering 465 square degrees, it ranks 38th of the 88 constellations in size.

Prominent stars and deep-sky objects

Stars

Canes Venatici contains no very bright stars. The Bayer designation stars, Alpha and Beta Canum Venaticorum are only of third and fourth magnitude respectively. Flamsteed catalogued 25 stars in the constellation, labelling them 1 to 25 Canum Venaticorum (CVn); however, 1 CVn turned out to be in Ursa Major, 13 CVn was in Coma Berenices, and 22 CVn did not exist.[11]

- Alpha Canum Venaticorum, also known as Cor Caroli ('heart of Charles'), is the constellation's brightest star, named by Sir Charles Scarborough in memory of King Charles I, the executed king of Britain.[12][lower-alpha 3] The English astronomer William Henry Smyth wrote in 1844 that α CVn was brighter than usual during the Restoration, as Charles II returned to England to take the throne, but gave no source for this statement, which seems to be apocryphal.[14] Cor Caroli is a wide double star, with a primary of magnitude 2.9 and a secondary of magnitude 5.6; the primary is 110 light-years from Earth. The primary also has an unusually strong variable magnetic field.[12]

- Beta Canum Venaticorum, or Chara, is a yellow-hued main sequence star of magnitude 4.25,[15] 27 light-years from Earth. Its common name comes from the word for joy.[12] It has been listed as an astrobiologically interesting star because of its proximity and similarity to the Sun.[16][17] However, no exoplanets have been discovered around it so far.[15]

- Y Canum Venaticorum (La Superba) is a semiregular variable star that varies between magnitudes 5.0 and 6.5 over a period of around 158 days. It is a carbon star and is deep red in color,[12] with a spectral type of C54J(N3).[18]

- AM Canum Venaticorum, a very blue star of magnitude 14, is the prototype of a special class of cataclysmic variable stars, in which the companion star is a white dwarf, rather than a main sequence star. It is 143 parsecs distant from the Sun.[19]

- RS Canum Venaticorum is the prototype of a special class of binary stars[20] of chromospherically active and optically variable components.

- R Canum Venaticorum is a Mira variable that ranges between magnitudes 6.5 and 12.9 over a period of approximately 329 days.[21]

Supervoid

The Giant Void, an extremely large void (part of the universe containing very few galaxies), is within the vicinity of this constellation. It is regarded to be the second largest void ever discovered, slightly larger than the Eridanus Supervoid and smaller than the proposed KBC Void and 1,200 times the volume of expected typical voids. It was discovered in 1988 in a deep-sky survey. Its centre is approximately 1.5 billion light-years away.[22]

Deep-sky objects

Canes Venatici contains five Messier objects, including four galaxies. One of the more significant galaxies in Canes Venatici is the Whirlpool Galaxy (M51, NGC 5194) and NGC 5195, a small barred spiral galaxy that is seen face-on. This was the first galaxy recognised as having a spiral structure, this structure being first observed by Lord Rosse in 1845.[12] It is a face-on spiral galaxy 37 million light-years from Earth. Widely considered to be one of the most beautiful galaxies visible, M51 has many star-forming regions and nebulae in its arms, coloring them pink and blue in contrast to the older yellow core. M 51 has a smaller companion, NGC 5195, that has very few star-forming regions and thus appears yellow. It is passing behind M 51 and may be the cause of the larger galaxy's prodigious star formation.[23]

Messier 51, the Whirlpool Galaxy, photographed by the Hubble Space Telescope.

NGC 4248 is located about 24 million light-years away.[24]

NGC 4242 is a dim galaxy in Canes Venatici.[25]

NGC 4631 photographed by the Hubble Space Telescope.

NGC 4707 is a spiral galaxy roughly 22 million light-years from Earth.[26]

Other notable spiral galaxies in Canes Venatici are the Sunflower Galaxy (M63, NGC 5055), M94 (NGC 4736), and M106 (NGC 4258).

- M63, the Sunflower Galaxy, was named for its appearance in large amateur telescopes. It is a spiral galaxy with an integrated magnitude of 9.0.

- M94 (NGC 4736) is a small face-on spiral galaxy with approximate magnitude 8.0, about 15 million light-years from Earth.[12]

- NGC 4631 is a barred spiral galaxy, which is one of the largest and brightest edge-on galaxies in the sky.[27]

- M3 (NGC 5272) is a globular cluster 32,000 light-years from Earth. It is 18′ in diameter, and at magnitude 6.3 is bright enough to be seen with binoculars. It can even be seen with the naked eye under particularly dark skies.[12]

- M94, also cataloged as NGC 4736, is a face-on spiral galaxy 15 million light-years from Earth. It has very tight spiral arms and a bright core. The outskirts of the galaxy are incredibly luminous in the ultraviolet because of a ring of new stars surrounding the core 7,000 light-years in diameter. Though astronomers are not sure what has caused this ring of new stars, some hypothesize that it is from shock waves caused by a bar that is thus far invisible.[23]

Ton 618 is a hyperluminous quasar and blazar in this constellation, near its border with the neighboring Coma Berenices. It possesses a black hole with a mass 66 billion times that of the Sun, making it one of the most massive black holes ever measured.[28] There is also a Lyman-alpha blob.[29]

Footnotes

- ↑ Hevelius' name for the northern dog, Asterion, is from the Greek αστέριον, meaning the 'little star',[6] the diminutive of αστηρ 'the star' or 'starry'. (Allen 1963, p. 115)

- ↑ Hevelius' name for the southern dog, Chara, is from the Greek χαρά, meaning 'joy'.(Allen 1963, p. 115)

- ↑ According to Warner,[13] it was originally named Cor Caroli Regis Martyris ('The Heart of King Charles the Martyr') for Charles I. Warner also notes that suggestions that the name was invented by Edmond Halley are erroneous.

References

- ↑ "Constellation Pronunciation Guide". 13 December 2006. https://www.space.com/3237-constellation-pronunciation-guide.html.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Canes Venatici, constellation boundary (Report). The Constellations. International Astronomical Union. http://www.iau.org/public/constellations/#cvn. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ↑ Allen 1963, p. 105; Kunitzsch 1959, pp. 123–124; Kunitzsch 1974, pp. 227–228; Kunitzsch 1990, pp. 48–49

- ↑ Apianus 1533; Allen 1963, p. 157

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Canes Venatici". http://www.ianridpath.com/startales/canesvenatici.html.; Ridpath & Tirion 2017, pp. 98–99

- ↑ Kunitzsch, P.; Smart, T. (2006). A Dictionary of Modern Star Names: A short guide to 254 star names and their derivations (2nd revised ed.). Sky Publishing. p. 22. ISBN 1-931559-44-9.

- ↑ Ridpath & Tirion 2017, pp. 98–99; Hevelius 1690

- ↑ Bečvář 1951

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Delporte, Eugène (1930). Délimitation scientifique des constellations. International Astronomical Union. https://books.google.com/books?id=v3XvAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "The IAU list of the 88 constellations and their abbreviations". http://www.ianridpath.com/iaulist1.html.

- ↑ Wagman, Morton (October 2003). Lost Stars: Lost, missing and troublesome stars from the catalogues of Johannes Bayer, Nicholas Louis de Lacaille, John Flamsteed, and sundry others. Blacksburg, VA: McDonald and Woodward. p. 366. ISBN 978-0-939923-78-6.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 Ridpath & Tirion 2017, pp. 98–99

- ↑ Warner, Deborah J.. The Sky Explored: Celestial cartography 1500–1800. Alan R. Liss, New York, 1979, p.150.

- ↑ Ridpath, Ian. "Canes Venatici". http://www.ianridpath.com/startales/canesvenatici.html#corcaroli.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 van Belle, Gerard T.; von Braun, Kaspar (April 2009). "Directly Determined Linear Radii and Effective Temperatures of Exoplanet Host Stars". The Astrophysical Journal 694 (2): 1085–1098. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/694/2/1085. Bibcode: 2009ApJ...694.1085V.

- ↑ de Mello, G. P.; del Peloso, E. F.; Ghezzi, L. (2006). "Astrobiologically Interesting Stars Within 10 Parsecs of the Sun". Astrobiology 6 (2): 308–331. doi:10.1089/ast.2006.6.308. PMID 16689649. Bibcode: 2006AsBio...6..308P.

- ↑ "Stars searched for extraterrestrials". PhysOrg.com. 2006-02-19. http://www.physorg.com/news10993.html.

- ↑ Ak, T.; Bilir, S.; Ak, S.; Eker, Z. (2008). "Spatial distribution and galactic model parameters of cataclysmic variables". New Astronomy 13 (3): 133–143. doi:10.1016/j.newast.2007.08.003. Bibcode: 2008NewA...13..133A.

- ↑ "V* RS CVn". SIMBAD. Centre de données astronomiques de Strasbourg. http://simbad.u-strasbg.fr/simbad/sim-basic?Ident=V*+RS CVn.

- ↑ VSX (4 January 2010). "R Canum Venaticorum". AAVSO Website. American Association of Variable Star Observers. http://www.aavso.org/vsx/index.php?view=detail.top&oid=5018. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ↑ Kopylov, A. I.; Kopylova, F. G. (February 2002). "Search for streaming motion of galaxy clusters around the Giant Void". Astronomy & Astrophysics 382 (2): 389–396. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20011500. Bibcode: 2002A&A...382..389K. https://www.aanda.org/articles/aa/pdf/2002/05/aa1614.pdf.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Wilkins, Jamie; Dunn, Robert (August 2006). 300 Astronomical Objects: A visual reference to the universe. Firefly Books. ISBN 9781554071753.

- ↑ "A cosmic atlas". European Space Agency. 24 July 2017. https://www.spacetelescope.org/images/potw1730a/.

- ↑ "Dim and diffuse". European Space Agency. 17 July 2017. https://www.spacetelescope.org/images/potw1729a/.

- ↑ "Astro-pointillism". European Space Agency. 19 December 2016. https://www.spacetelescope.org/images/potw1651a/.

- ↑ O'Meara, Stephen James (January 2002). The Caldwell Objects. Sky Publishing Corporation. p. 126. ISBN 0-933346-97-2.

- ↑ Shemmer, O.; Netzer, H.; Maiolino, R.; Oliva, E.; Croom, S.; Corbett, E.; di Fabrizio, L. (2004). "Near-infrared spectroscopy of high-redshift active galactic nuclei: I. A metallicity-accretion rate relationship". The Astrophysical Journal 614 (2): 547–557. doi:10.1086/423607. Bibcode: 2004ApJ...614..547S.

- ↑ Li, Jianrui; Emonts, B.H.C.; Cai, Z.; Prochaska, J.X.; Yoon, I.; Lehnert, M.D.; Zhang, S.; Wu, Y. et al. (25 November 2021). "Massive Molecular Outflow and 100 kpc Extended Cold Halo Gas in the Enormous Lyα Nebula of QSO 1228+3128". The Astrophysical Journal Letters 922 (2): L29. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ac390d. Bibcode: 2021ApJ...922L..29L.

Bibliography

- Allen, Richard Hinckley (1963). Star Names: Their lore and meaning. New York, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-21079-0. https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/Topics/astronomy/_Texts/secondary/ALLSTA/home.html.

- Apianus, Petrus (1533) (in la). Horoscopion generale. https://books.google.com/books?id=D0xZAAAAcAAJ.

- Bečvář, Antonín (1951). Atlas Coeli (II – Catalogue 1950.0 ed.). Czechoslovak Astronomical Society.

- Hevelius, Johannes (1690) (in la). Firmamentum Sobiescianum.

- Kunitzsch, P. (1959) (in de). Arabische Sternnamen in Europa. Otto Harassowitz.

- Ptolemäus, Claudius (1974). Der Almagest: Die Syntaxis Mathematica des Claudius Ptolemäus in arabisch-lateinischer Ūberlieferung. Otto Harassowitz.

- Ridpath, Ian; Tirion, Wil (2017), Guide to Stars and Planets (5th ed.), Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691177885

- Kunitzsch, P. (1990) (in de). Der Sternkatalog des Almagest die arabisch-mittelalterliche Tradition. II Die lateinische Ūbersetzung Gerhards von Cremona. Otto Harassowitz.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Canes Venatici. |

- Photos of Canes Venatici and the star clusters and galaxies found within it on AllTheSky.com

- Clickable map of Canes Venatici

- Photographic catalogue of deep sky objects in Canes Venatici (PDF)

Coordinates: ![]() 13h 00m 00s, +40° 00′ 00″

13h 00m 00s, +40° 00′ 00″

|

Categories: [Canes Venatici] [Northern constellations]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 08/31/2025 10:10:13 | 6 views

☰ Source: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Astronomy:Canes_Venatici | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

KSF

KSF