Battle Of Gettysburg

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle of Gettysburg was the climax of the Gettysburg Campaign, a decisive defeat for the Confederacy in the American Civil War from July 1 to July 3, 1863. General George Meade commanded the Union Army of the Potomac while General Robert E. Lee led the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. This mere 3 days of fighting caused 51,000 casualties, the most of the War, wiping out 37% of the Confederate army and 27% of the Union's. It was the largest military battle ever on American soil, involving more than 170,000 soldiers, and today is the most-visited Civil War site (2 million annually).[3] Making his famous Gettysburg Address at the battle site 4 months later, Abraham Lincoln converted to Christianity and "[i]n the days that followed, Abe Lincoln worshiped regularly at New York Avenue Presbyterian Church, not only on Sunday, but at the Wednesday evening prayer service as well."[4]

Known simply as "Gettysburg", this unexpected epic battle included many strategic mistakes that have been studied and analyzed ever since. Four months after the conflict, it was the site of the famous Gettysburg Address, in which Abraham Lincoln inserted "under God" into his speech after "this Nation," and in 2016 it was the site of a speech by candidate Donald Trump in his campaign for the presidency. At least one expression has become part of the English language due to this battle: "Pickett's Charge," which is an ill-advised, self-destructive frontal advance against an adversary. 160,000 combatants from both sides.

General Robert E. Lee took his army into Pennsylvania to capture army supplies (shoes, mostly[5]), boost morale, and destroy the will of the North. It was only by chance that he collided with the main Union army led by General George Meade. Lee did well the first two days but was routed on the third. He was then trapped but Meade's failure to pursue allowed Lee's army to escape.

Contents

Lee moves north[edit]

On preparations and strategies, see Gettysburg Campaign.

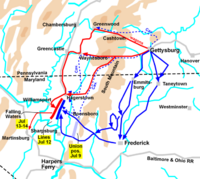

Up until now the Confederate army had generally been successful in pitched battles, although they were always outnumbered in men and supplies. While Lee was used to fighting with inferior numbers he was also severely handicapped at Gettysburg by the recent loss of his best general, Stonewall Jackson, as well as the absence of his "eyes"—the cavalry under J.E.B. Stuart, who he depended on reconnaissance. Lee never knew how close and dangerous the Union army was. Another problem was the new division of the Confederate Army by General Lee. There were originally two corps, one under General James Longstreet, the other under General Jackson. With Jackson's death, Lee decided to divide the second corps into two new ones: one under General Richard S. Ewell, the other under A.P. Hill. Lee moved north through Maryland and into Pennsylvania, close to a small town called Gettysburg.[6]

Hooker and the Union Army[edit]

While Lee's army made preparations to march, the Army of the Potomac rested in their old winter camps opposite Fredericksburg while its commander, Major General Joseph Hooker, wrestled with innumerable predicaments. Not only were Lee's intentions perplexing Hooker, his relationship with War Department officials in Washington had become almost hostile. The flamboyant Hooker had rebuilt morale and discipline in the army after the disastrous "Mud March" in the winter of 1863, and in late April brilliantly moved the bulk of his forces around Lee's army concentrated at Fredericksburg. Despite the Union advantage, Lee and his top general "Stonewall" Jackson, countered Hooker's strategy and soundly defeated him. Hooker's bluster and bravado before the campaign meant nothing after his miserable failure at the Battle of Chancellorsville. Many in the War Department had lost faith in the general's abilities, including President Lincoln who soon believed Hooker unsuited to contend with Lee.

Hooker approved a plan to probe Lee's defenses and on June 9, the army's cavalry under General Alfred Pleasanton made a surprise attack on General "JEB" Stuart's cavalry camps near Brandy Station, Virginia. Pleasanton's troopers surprised Stuart, but withdrew when Confederate infantry were sighted approaching the battlefield. From this information, Hooker realized that Lee's forces were no longer concentrated in front of him at Fredericksburg. Yet, indecision seemed to strike General Hooker again. He waited for nearly a week before ordering his troops to break camp and then marched cautiously northward, keeping his army between Washington and the suspected Confederate route of march. By this time, Lee's troops had already defeated a Union force at Winchester, Virginia, and crossed the Potomac River into Maryland.

Despite the loss of Stonewall Jackson, the Army of Northern Virginia was never stronger both in manpower and high morale than in the summer of 1863. "It was an army of veterans," recalled A.H. Belo, Colonel of the 55th North Carolina Infantry, "an army that had in two years' time made a record second to none for successful fighting and hard marching." In mid-June, Lee's soldiers crossed the Potomac River and stepped into a rich land barely touched by the war. Except for some persistent Union cavalry units, the southerners tramped along unopposed as militia units retreated from their path leaving the land and its residents to the mercy of the Confederates.

Looting Pennsylvania[edit]

For Lee's men who had been living for months on reduced rations, Maryland and Pennsylvania were bursting with plenty. "I can hardly believe that a rebel army has actually left poor Virginia for a season," wrote Major Eugene Blackford of the 5th Alabama Infantry. "Of course there is no end of milk and butter which our soldiers enjoy hugely." Encounters with the civilian population of Maryland and Pennsylvania made for good subject matter in letters home such as that of Private William McClellan of the 9th Alabama Infantry, who described Pennsylvanians as, "the most ignorant beings of the world. They don't care how long the war lasts so they are not troubled." Like many of his comrades, McClellan especially detested the females who, "would not look at a Rebel, they would turn up their nose and toss their heads to one side as contemp(t)uously as if we were high way Robers."

"There's hardly any sickness or straggling in the army," added Private Eli Landers, 16th Georgia Infantry. "We have a large army now in Pennsylvania and it is good and in fine spirits. We intend to let the Yankey Nation feel the sting of the War as our borders has ever since the war began." Despite the feelings of retribution that Landers and his fellow soldiers had, on June 21, General Lee issued Order No. 72, which forbade the seizure or theft of private property. Federal property was another matter. Confederate quartermasters used their authority to seize Federal stores found in government warehouses, post offices, and railroad depots. Anything that was of use to the southern army was quickly inventoried and carried away, much to the dismay of Federal authorities. Quartermasters also purchased needed supplies from merchants and privately owned storehouses. Soldiers begged for food from civilians and were often rewarded by farmers too frightened to refuse the Confederate money handed them in payment. Apart from some minor infractions, the Confederates obeyed General Lee's order and respected civilian property.

Yet, northern store owners found themselves in a quandary when their shops were suddenly filled with armed men who helped themselves to boots and shoes before inspecting other goods the owner may have in stock. Cloth, hats, canned foods and other groceries were in high demand. Much to the storekeeper's dismay, the Confederates paid in southern script that was worthless above the Mason–Dixon line. But most accepted the Confederate paper hoping that it could be eventually exchanged for Federal notes. Many more were careful to hide some of their inventory before the Confederates arrived or be strangely absent with shop doors bolted when the dusty column of Confederates entered a town whose civilian population was already on edge from rumors of rampant thievery and towns burned to the ground. Many of these wild rumors centered around the feared "Louisiana Tigers", rumored by many northerners to be the toughest southern soldiers and the most lawless. Such was the case when the first Confederate column, commanded by General Jubal Early entered Gettysburg, demanding supplies and money. "After matters had been satisfactorily arranged between our Burgess and the Rebel officers," recalled Fannie Buehler who resided on Baltimore Street, "the men settled down and the citizens soon learned that no demands were to be made upon them and that all property would be protected. Some horses were stolen, some cellars broken open and robbed, but so far as could be done, the officers controlled their men. The 'Louisiana Tigers' were left and kept outside of town."

This first encounter was not without a bloody mishap. A small squad from the 21st Pennsylvania Emergency Cavalry was chased out of town and Private George Sandoe was shot and killed, the first official casualty of the coming battle. Early did not tarry for long in Gettysburg, but moved on toward York and Columbia where he was stopped by Pennsylvania militia that burned the bridge over the Susquehanna River. Meanwhile, other Confederate forces had occupied a large area of south central Pennsylvania and some had even closed on Harrisburg, threatening the state capitol.

Meade in command[edit]

The slow pursuit of Lee by the Army of the Potomac not only alarmed War Department officials but shocked governors of northern states who clamored for something to be done to stop the rebel invasion. Political pressure on the Lincoln administration added to the tug of war between General Hooker and the US War Department, which finally ended on June 28 as the Army of the Potomac concentrated at Frederick, Maryland. Completely frustrated by the mistrust and lack of support from War Department officials, General Hooker requested to be relieved of command, which was quickly granted.

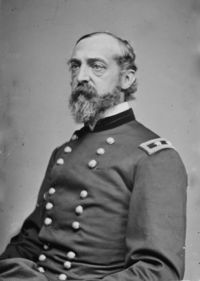

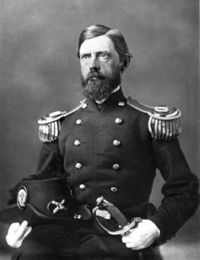

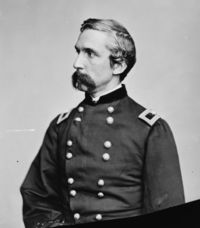

Major General George Gordon Meade was ordered to take command of the army. "I have been tried and condemned", the surprised general remarked after receiving word of his appointment. Using traces of information known on Lee's whereabouts and objectives, Meade decided to send the army north to feel for the enemy and draw Lee into battle on a defensive line he wanted to establish on Pipe Creek, Maryland. The very next day, the Army of the Potomac marched out of their camps to search for the Confederates in Pennsylvania.

The Opening Shots[edit]

On June 30, Confederate troops left their camps at Cashtown and marched toward Gettysburg in search of supplies. Upon reaching the edge of Gettysburg, scouts spied a column of Union cavalry south of town, closing fast. Under orders not to initiate a battle, the Confederates returned to Cashtown where they reported the encounter to their commander, Lt. General A.P. Hill. Hill agreed to send two divisions of his corps toward Gettysburg the next day to investigate the arrival of the mystery cavalrymen and the stage was set for the opening of the battle on July 1, 1863.

The First Day[edit]

On the morning of June 30, a Confederate column under Brigadier General James J. Pettigrew approached Gettysburg on the Chambersburg Road. Halting his men outside of town, the general rode ahead to Seminary Ridge from which he had a clear view of Gettysburg and the land around it. Within a few minutes he was startled by the report of a blue-clad column approaching Gettysburg from the south. Were these men just more bothersome Yankee militia or troopers from their old nemesis the Army of the Potomac? Under strict orders not to engage in any fighting, he ordered his troops to reverse their course, back toward Cashtown, Pennsylvania. What to do about this column of soldiers would be the decision of his corps commander, General A.P. Hill to whom Pettigrew would report that afternoon.

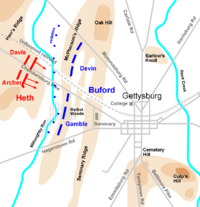

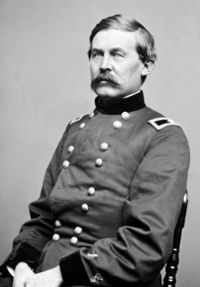

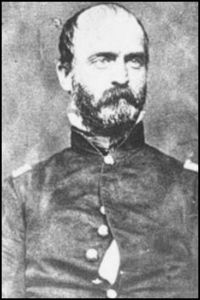

The commander of the mystery column was Brig. General John Buford, whose troops were not "Yankee militia" but a full division of veteran cavalry. His horsemen were the advance of one wing of the Army of the Potomac, moving north from the vicinity of Frederick, Maryland. General Buford also had unanswered questions as he watched the southern column march away- had they found what may be a large portion of the Confederate army then raiding south-central Pennsylvania? Buford's instinct told him these Confederates would return and he decided to keep his troops positioned around Gettysburg. Headquarters were soon established in the Globe Hotel in Gettysburg, where Buford issued orders for his troopers to picket the roads west, north and east of town. He then penned a message to General John Reynolds, commander of the First Corps, camped at Marsh Creek eight miles south of Gettysburg. Reynolds received the report, which outlined Buford's intention of resisting any southern advance toward Gettysburg. Reynolds replied that he would march to the cavalry officer's support at first light.

Meanwhile, Confederate commanders met at Cashtown eight miles west of Gettysburg, to discuss their course of action. Under orders from General Lee not to get involved in a full-scale battle, Hill and his officers obviously believed that only troublesome militia were in their way. General Hill received Pettigrew's report of his encounter and decided to send a larger force toward Gettysburg the next day to investigate the Union troops seen there and, if time allowed, look for supplies. Showers and light rain that evening would also help keep down the dust and dirt on the roads, making for a pleasant march.

Lt. Marcellus Jones of the 8th Illinois Cavalry, was in charge of a picket line that intersected the Chambersburg Road three miles west of Gettysburg. Dawn was just breaking on the morning of July 1, 1863, when, in the distance, cavalrymen in the main post on the road could discern the sound of hushed conversations, the clink of metal cups and canteens, and the shuffle of boots and shoes on the road surface. A sergeant ran to find Lt.Jones, who had just returned to the reserve position with bread and butter purchased from a nearby farm. Jones immediately rode with the sergeant to the post and peering through the early morning haze, he spotted a gray column of soldiers, lazily swinging down the road toward him. Borrowing a carbine from his sergeant, the lieutenant took aim at a mounted figure in front of the column and fired. The column abruptly stopped and the horseman pointed out the Yankee picket post. Behind him, a wisp of wind revealed a red banner. There was no doubt who these men were- Confederates! Jones handed a brief message to a courier, instructing him to ride as fast as possible to General Buford. Seconds later a cannonball bounded down the road, scattering the Union troopers as Southern bullets whined overhead. The Battle of Gettysburg had begun.

The battle begins[edit]

The southerners spotted by Jones' picket post were veteran troops of Major General Henry Heth's division, leading the march toward Gettysburg that morning. Well-liked by General Lee, (Heth was the only Confederate officer Lee addressed by his first name), the plucky general was uncertain of what lay ahead of him, be it Pennsylvania militia or troops from the Army of the Potomac, so he ordered his lead unit to deploy in a skirmish line and drive away the blue-clad troopers. The job was given to the 5th Alabama Infantry Battalion, which advanced in good order and quickly encountered groups of cavalrymen who fired on them from the protection of fences and trees. Three miles away at Gettysburg, General Buford calmly awaited the report knowing full well that a thin line of cavalrymen were no match against solid ranks of infantry. Though Reynolds' corps had started toward town that morning, Buford had to wonder if they would arrive in time before he was forced to retreat.

The skirmishing continued for over an hour, the troops passing over a series of rolling ridges farm fields until Buford's men reached Willoughby Run, a shallow stream that bordered the Edward McPherson Farm on the Chambersburg Pike. Through the center of the farm is north-south ridge that lies parallel to the run, and was a good position from which to cover the bridge that spans it. From the observatory of the Lutheran Seminary on Seminary Ridge, Buford watched his horsemen gather on McPherson's Ridge and knew that time was running out. His men had been lucky up to this point- the Confederates had only advanced as skirmishers and not pushed forward in solid battle lines. But southern pressure was steadily growing and the clouds of dust rising from the pike were an obvious sign of more Confederates troops moving toward Gettysburg. Confederate artillery was just then pulling into line on Herr's Ridge west of Willoughby Run, which meant the Confederate commander was done with skirmishing and an infantry attack was sure to follow. General Heth had indeed discovered how slender the Union line was and having arrived at Herr's Ridge, decided it to be the perfect point from which to launch an attack and drive away these pesky Union soldiers once and for all. With his artillery unlimbered and ready to fire, Heth ordered his two lead infantry brigades under Brig. General James Archer and Brig. General Joseph Davis to go forward. With red battle flags unfurled, Archer's and Davis' Confederates set out toward McPherson's Ridge.

Arrival of Reynolds[edit]

From his post in the observatory of the Seminary roof, General Buford was intently observing the fighting when he was startled by a familiar voice calling from below: "How goes it, John?" Buford immediately recognized his old friend Reynolds. "The devil's to pay!", he replied and rushed down to meet with the infantry commander. The two officers quickly discussed the situation and rode together to McPherson's Ridge. Reynolds chose the ridge as the best location to establish an artillery and infantry battle line, but southern pressure on Buford's men was mounting and Reynolds knew his men would have to move fast. With a casual salute, Reynolds rode off to hurry his troops forward. It was the last time Buford would see the general alive.

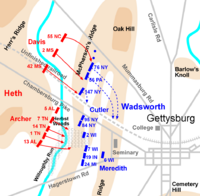

Within a half-hour, the vanguard of Reynolds' corps arrived near the Seminary and moved toward the McPherson Farm, while more soldiers filed into the field west of the school building. By this time, the advance of General Archer's brigade had reached the woods and field south of McPherson's farm and turned their attention to the blue-clad infantry forming in their front. This was the famous "Iron Brigade", which had won its reputation on the battlefields of Second Manassas, Antietam, and Fredericksburg, and was commanded by Brigadier General Solomon Meredith. Meredith had just ordered the first regiment of the brigade, the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry, to deploy into battle line when the first volley from Archer's men struck them from the edge of the woods. The black-hatted Wisconsin soldiers had not even had a chance to load their rifles, but with bayonets fixed and little more encouragement required, the 2nd Wisconsin lunged into the woods. Caught off guard by the sudden counterattack, the Confederates fired a few scattered shots and then retreated in disorder through the woods and across Willoughby Run, with the Union soldiers in hot pursuit. A number of southerners found themselves cut off and were taken prisoner including General Archer, grappled from the southern ranks by Private Patrick Maloney of the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry.

Riding behind the 2nd Wisconsin, General Reynolds cheered the men on as they scrambled into the woods. The general turned toward Seminary Ridge to see what troops and officers were following, when he suddenly slumped in his saddle. A staff officer rushed to the general's side as he toppled from his horse. Cradling the general, the officer felt blood on the back of Reynolds' head and turning him over saw that a bullet had cleanly struck the general in the right temple, killing him instantly. John Reynolds was the highest-ranking officer of either side to lose his life at Gettysburg and was the general who had recommended General Meade to replace General Hooker in command of the Army of the Potomac. The general's body was borne from the field in an ambulance, escorted by his heartbroken staff officers. He was buried in his hometown of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, barely 40 miles away from the battleground where he had lost his life.

McPherson's Farm[edit]

Fighting also erupted in fields north of the McPherson Farm, where Davis' Brigade of Mississippi and North Carolina regiments routed part of General Lysander Cutler's Union brigade. When success seemed within their grasp, Davis' regiments were thrown back in confusion by a rapid Union infantry charge and accurate artillery fire. Taking refuge in the bed of an unfinished railroad, Davis' troops desperately fought back as Union troops formed in their front and then charged the southerners. At the center of the charge was Lt. Colonel Rufus Dawes whose 6th Wisconsin Infantry, also from the Iron Brigade, successfully trapped many of the Confederates in the deepest section of the railroad cut. Sgt. Frank Waller wrested the colors of the 2nd Mississippi Infantry from the flag bearer in the railroad bed during the short, deadly struggle. There was no escape for the southerners in the cut soon covered by members of the 6th Wisconsin, 95th New York and the 14th Brooklyn (84th New York), which threw troops across the railroad bed west of the cut. Mercifully the Union troops held their fire and called for the Confederates to surrender. Over 200 men from Davis' brigade were now prisoners.

A lull in the battle ensued as both sides withdrew to restore order and wait for the arrival of additional troops and artillery. Casualties in this early contest were severe for both sides and though the Union army had lost one of its most distinguished generals, the Confederates had suffered more than their Union counterparts. General Archer was captured and the better part of two brigades were knocked out of action for the remainder of the day. Realizing that he was facing more than Pennsylvania militia, General Heth wisely decided to wait for the remainder of his division and artillery to arrive on the battlefield, and then to ask permission of General Hill to continue the attack. General Abner Doubleday, having assumed command of the First Corps upon the death of General Reynolds, arranged his troops in a defensive line starting on McPherson's Ridge. He used troops of General Robinson's Division to extend the line northward on Oak Ridge, which is the northern extension of Seminary Ridge, and then sent an aide to find General Howard to report his position.

Major General Oliver Otis Howard, commander of the Eleventh Corps, arrived on the battlefield that morning at approximately the same time that Reynolds was killed. Howard climbed to the roof of a building in Gettysburg where he spotted some Union troops break through the woods on Seminary Ridge and run toward town. Believing that the First Corps had broken and was in retreat, Howard fired off a desperate message to General Meade at Taneytown, Maryland, that the situation was bad and reinforcements were needed. (The message had unfortunate consequences for General Doubleday, whose generalship on July 1 would later be called into question.) Howard ordered General Carl Schurz to take command of the Eleventh Corps as he assumed command of all Union troops on the field, vice Reynolds and Doubleday, and then sent the Eleventh Corps into the fields north of Gettysburg to bolster the First Corps right flank. One division of the corps was placed on Cemetery Hill just south of town as a reserve force. This proved to be a very important decision that day, securing what was to be a vital position for the Union army.

General Meade was still at Taneytown when he received Howard's disturbing message that included news of Reynolds' death. Though shaken at the loss of one of his closest friends in the army, Meade immediately decided to send another trusted corps commander, Major General Winfield Scott Hancock, north to Gettysburg to investigate the situation and take charge of the troops there. Hancock immediately set out for the battlefield.

The brief noon-time lull in infantry movement gave commanders on both sides time to plan and augment their battle lines. Union troops followed a jagged line extending northward from the McPherson Farm along Oak Ridge and then east to a small knoll near the county Alms (Poor) House. Confederate forces were arrayed against this line in heavier numbers with more troops expected to arrive at any moment. Though the Union infantry was outnumbered, the First Corps artillery, commanded by Colonel Charles Wainwright, did have an advantage in positions where they could sweep the routes of Confederate attacks with shell and canister.

General Hill did not accompany Heth's troops that morning, so was unaware of his dilemma near Gettysburg. Shortly before noon a small entourage of mounted officers arrived at his headquarters, led by a stern-faced General Lee. The generals were discussing the location of Hill's corps and possible enemy sightings when they were interrupted by the boom of cannon coming from the direction of Gettysburg. Concerned, Lee chose to ride ahead toward the sound of the guns accompanied by Hill and both staffs. It was on the Cashtown-Gettysburg Road where they met a courier from General Heth, bearing news that a large Union force had been encountered and stating confidence they could be driven off. Lee hurried on toward the battle that he was not yet ready to give on Union soil.

The battle renewed[edit]

Heth renewed his attack against the Union positions on the McPherson Farm between 1:30 and 2 o'clock. Supported by Maj. General William Pender's division, Heth sent his two remaining brigades forward to hit a re-enforced line posted behind strong farm fences and in the woods above Willoughby Run. Doubleday's line was stretched thin, but his division and brigade commanders shifted troops around to strengthen weak areas of the line. Determined to stand their ground. the Union troops would not budge no matter how much pressure the Confederates applied. On the McPherson Farm and adjacent Herbst Farm, the Iron Brigade fought toe to toe with Brig. General James J. Pettigrew's North Carolina Brigade. At one point in the battle, opposing lines blazed into one another barely twenty paces apart. Two regiments were especially hard hit- the 24th Michigan Infantry and the 26th North Carolina Infantry both suffered losses of 70%. Twenty one year-old Colonel Henry Burgwyn Jr., commanding the 26th North Carolina, was mortally wounded while leading one of the last charges against the 24th Michigan, shot, "through both lungs. He fell with the colors (of the 26th) wrapped around him."

Spread out between York and Carlisle, Pennsylvania, Lt. General Richard S. Ewell's Corps had been ordered to consolidate in the Gettysburg area on July 1. Setting out early that morning, Ewell's 8,500 troops closed in on Gettysburg from the north and northeast. Maj. General Robert Rodes' Division was the first to arrive and attacked the right flank of the Union First Corps on Oak Ridge, the northern extension of Seminary Ridge. The Union troops on Oak Ridge were from a division commanded by Brig. General John C. Robinson, of the First Corps. Robinson only had Colonel Henry Baxter's brigade of New York, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania regiments at his disposal and observing the disjointed southern attack, shifted his men to meet each threat upon his position. One by one Baxter's troops repulsed the Confederate assaults and annihilated the North Carolina brigade commanded by Brig. General Alfred Iverson. Iverson's soldiers marched into an open field unsupported, not realizing the strength of the Union position behind the stone wall that lay ahead on Oak Ridge. Over 1,100 Union soldiers rose and fired into the southerners from less than 100 feet away. Few escaped the terrible fire unscathed. Many surrendered to Baxter's men as they rushed into the field to take prisoners and capture flags from their fallen bearers.

With Baxter's regiments running low on ammunition, General Robinson called in Brig. General Samuel Paul's brigade, which replaced Baxter's troops just before General Rodes renewed his attack. Paul's men were soon fighting for their lives as Rodes shifted regiments from other commands into the attack. General Paul was horribly wounded when a bullet struck him in the face, passing through both eyes. Remarkably, he survived this horrific wound. Ammunition began to run out. A Confederate brigade succeeded in reaching woods behind Paul's regiments, threatening to cut them off from the rest of the First Corps. A retreat was ordered to follow Oak Ridge and rejoin the corps. The brigade withdrew, all except for one regiment, the 16th Maine Infantry. The Maine soldiers stubbornly held onto their corner of the stone wall and did not leave until the last moment. Many of the regiment were taken prisoner, including its commander Colonel Tilden. So that their flag would not be taken, the 16th's soldiers ripped the standard into small pieces, each of which were taken by the men.

While Rodes dealt with Baxter and Paul on Oak Ridge, Brig. George Doles' brigade of Georgia troops sparred with Schurz's Eleventh Corps positioned in the fields north of Gettysburg. Though he was outnumbered, Doles' superb generalship kept the Yankee troops, who appeared shaky from the beginning, off guard. Poor morale, exhaustion, and the exposed position of the Eleventh Corps troops, many who were German and Polish immigrants, contributed to the disaster about to befall them. Another division of Ewell's infantry under Brig. General Jubal Early, arrived via the Harrisburg Road at approximately 3 P.M. Understanding the advantage of his position, Early deployed his troops and artillery so that he could sweep behind the Union line.

A thunderous roar of artillery announced his arrival as ranks of southern infantry set out across Rock Creek. Seeing his opportunity, General Doles sent his brigade forward and the two wings of the Confederate column came together around "Barlow's Knoll". Though some regiments fought with determination, the Confederate attack broke the line and retreat turned into a panicked rush into Gettysburg. A single Union brigade under Colonel Wladimir Kryzanowski, a Polish immigrant, attempted to make a stand, but were swept aside by overwhelming numbers. Victorious Confederates overran the remaining feeble resistance, a small brigade of Union troops under Colonel Charles Coster, and entered Gettysburg.

West of town, General Doubleday and his First Corps were also in deep trouble. After several hours of fighting marked by great gallantry on both sides, casualties had whittled down the corps' effective force to less than half of the Confederates who seemed to continually be sending in fresh troops. Doubleday withdrew his command into a consolidated position on Seminary Ridge where the men threw down fence rails for a barricade and waited as the Confederates formed on McPherson's Ridge for a final assault. But driving Doubleday's command from Seminary Ridge proved more deadly than Hill and his division officers had planned. The initial Confederate attack met a storm of concentrated artillery and musketry fire that nearly destroyed General Alfred Scales' North Carolina brigade and severely crippled part of a South Carolina brigade commanded by Colonel Abner Perrin. Outnumbered, low on ammunition and with his rear threatened, there was nothing more Doubleday could achieve by holding Seminary Ridge. There was no alternative but to retreat through Gettysburg to Cemetery Hill.

The Union line collapses[edit]

Despite a severe cross fire and heavy casualties suffered during their charge, Colonel Perrin's South Carolinians exploited a narrow gap in the Union line and raced onto Seminary Ridge just as the Union officers ordered their men to pull out. Perrin ordered two of his regiments to pursue the retreating Federals and the incensed South Carolinians raced after the refuges in blue, taking prisoners and shooting down those who refused to surrender. What began as an orderly retreat soon turned into a confused race through Gettysburg as soldiers trotted through unfamiliar streets and alleys while other lost souls plowed into the crowd from intersecting streets. Adding to the chaos was the lack of orders to direct the refugees to Cemetery Hill, the Union rallying point. Lost soldiers ran from one street to another to find themselves confronted by armed Confederates. Others took refuge in cellars and buildings, only to be rooted out and taken prisoner. Wounded soldiers collapsed in doorways and churches where Gettysburg civilians, such as 21 year-old Sallie Myers, tried to tend to their wounds. Terrified civilians took to their cellars while above them the floors creaked with the heavy sounds of boots. Rifle shots echoed through the streets. Peering from his cellar window, one man was horrified by the sight of a Union soldier shot down in the street in front of his home. Everywhere there were Confederate soldiers with rifles and fixed bayonets, looking for Yankees who had not made their escape.

Christ Lutheran Church on Chambersburg Street was one of the first churches in Gettysburg to be used as a hospital. Wounded were laid on boards set on top of church pews while operations took place in one of the front rooms. The monument in front of the church is to Chaplain Thomas Howell of the 90th Pennsylvania Infantry. Confronted by Confederate soldiers during the Union retreat, Howell refused to surrender his sword and was shot dead on the church steps.

Those who did find their way to Cemetery Hill were confronted by General Winfield Scott Hancock, sent to Gettysburg by General Meade to assume command after the death of Reynolds. Galloping onto Cemetery Hill at 4:30, Hancock beheld a depressing sight: streets filled with masses of Union troops without order, lathered teams of horses pulling artillery limbers forcing their way through the crowd, and wounded soldiers limping or staggering along as if drunk. For all purposes the entire Union force at Gettysburg had been routed. Joined by General Howard, Hancock rode into the center of the Baltimore Pike and immediately barked orders for officers to rally their commands and find shelter on the hillside. Hancock's commanding presence and stern demeanor was enough for most of the exhausted soldiers to search for their regiments and fall into ranks. Hancock paused just long enough to send a report to General Meade before returning to the task of establishing a strong center for the remainder of the Union line to form upon. By nightfall, reorganized regiments had established a line of defenses from Cemetery Ridge to Culp's Hill with Cemetery Hill at the fortified center.

Once he arrived on the battlefield that afternoon, General Lee appreciated the advantages gained by the sweat and toil of his troops and gave his consent for the attack to continue. He entered Gettysburg on the trail of his soldiers, very concerned with the growing Union strength on Cemetery Hill and the adjacent Culp's Hill. Lee sent a message to General Ewell to take the hills "if practicable"; but Ewell was unable to consolidate his forces to attack before nightfall and the battered Union troops remained undisturbed throughout the evening. Additional Union troops arrived to bolster the Union defenses, followed by General Meade who reached the field around midnight. Thanking Hancock for his services, Meade set about planning for the next day's battle. Though two corps had been defeated and thrown back, their heroic stance had bought time for the remainder of the Army of the Potomac to close on Gettysburg and camp on a position so strong that Lee would be hard pressed to break it. Whether he was fully ready or not, Lee had been drawn into battle and Meade was prepared to fight it to the finish at Gettysburg.

General Lee's headquarters tent was pitched near the Thompson home on the Chambersburg Pike, an ideal location adjacent to the Lutheran Seminary building where the general could utilize the rooftop observatory. Seating himself by the light of a candle in his tent, Lee pondered the day's events. Though his soldiers had driven the Union forces from the field in disarray and captured the town, he certainly had not won the battle necessary to accomplish all of his objectives in Pennsylvania. Losses in Heth's and Rodes' Divisions had been staggering, but the remainder of his army was within a day's march, defiantly confident and fit to fight for another day at least. Against his desires, the ground for the great battle had been chosen and the growing strength of the Union position on Cemetery Hill and Culp's Hill concerned him. More fighting clearly lay ahead and Lee had to satisfy himself that the hills would be taken the following day. If only he knew more of where the rest of the Union army was located and how close they were to Gettysburg. That had been "Jeb" Stuart's job and Lee had not heard from him for almost two weeks.

In more than twelve hours of fighting, approximately 16,000 soldiers were killed, wounded or captured during the first day of battle.

The Second Day[edit]

The Confederate victory on July 1 was not conclusive. The Army of the Potomac was still present near Gettysburg and by early morning held a strong position on the hills and ridges south of town in a horseshoe-shaped line bristling with artillery. With its right anchored on Culp's Hill, the line stretched through Cemetery Hill and southward to a knoll on Cemetery Ridge, north of two hills that locals referred to as the Round Tops. Troops who had arrived overnight were also arrayed at the base of the smaller of the two hills, partially cleared of tree growth to reveal large boulders and hundreds of rocks, known as Little Round Top. Despite the loss of Reynolds and the majority of two army corps, Meade was satisfied with his army's position, not only for defense but for an attack as well. Union troops of the Twelfth Corps east of Culp's Hill may have an opportunity to attack Lee's flank if possible. But as the morning sun peeked through overcast, rainy skies, the commanding general decided to pull those troops into the horseshoe and wait for Lee to make the next move. The question was, from which direction would the Confederate attack come? Having sought opinions from his most trusted officers, Meade decided to bring forward the remainder of his army, repulse any Confederate attack, and if the opportunity arose, he would, in turn, strike at Lee.

Weakness on the flanks[edit]

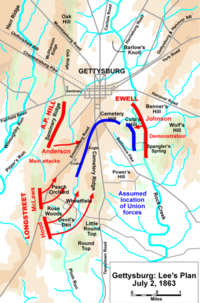

Lee rose before dawn to formulate his plan of attack for the day. In the early morning light he surveyed the strong Union position and realized that a weakness might lay on the Union flanks. A simultaneous strike on both the right and left of Meade's position could roll up the Union line toward Cemetery Hill. The weakest flank was the Union left, which did not appear to be anchored on any high ground including the Round Tops at the southern base of Cemetery Ridge. After consultation with corps commanders A.P. Hill and James Longstreet, Lee dictated orders that Hill would remain in position at the Confederate center while General Longstreet's Corps would attack on the right and General Ewell's Corps would strike on the left. Both had to strike at the same time to throw the Union off balance, not giving Meade time to shift troops to the threatened areas.

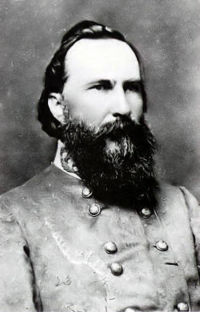

Ewell's men were close to the field that morning, but James Longstreet's were not. Two divisions of his corps had stopped for the night several miles away from the field with a third too far away to assist that day. The two divisions under Generals John Bell Hood and Lafayette McLaws set out at 4 AM that morning but had not yet arrived near Gettysburg while Lee was formulating plans for an early morning assault. By the time they arrived it was after 8 o'clock, and Lee was forced to alter his timetable. Orders were finally re-issued at mid morning for General Longstreet to put his troops in motion. Not thrilled with his assignment because of the unfamiliarity of the ground and his desire to fight defensively, a disgruntled Longstreet put Hood and McLaws in motion on secondary roads south. After considerable delay, the march began filled with hope as the early morning drizzle had ended and the sky cleared. Yet misinformation and poor scouting thwarted the march. The day grew warm and the roads turned dusty under the tramping feet of 16,000 soldiers. Midway to the assigned positions, the lead scouts discovered that the road crested a ridge where signalmen on Little Round Top could easily spot the Confederate column. Somehow this critical location had not been reported by Captain Samuel R. Johnston, the officer in charge of an early morning reconnaissance to that area. Longstreet's men had to counter-march, or retrace their route back to another road that proved a more secluded route toward the southern tip of Seminary Ridge.

It was not until 3:30 PM when Hood's and McLaws' men finally reached their positions and formed battle lines having marched an exhausting 18 miles since sunrise. Very few of their troops had the opportunity to rest or fill empty canteens before the signal guns were fired to begin the assault.

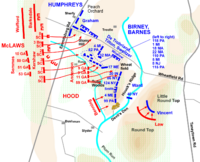

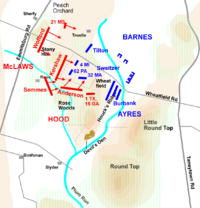

Situated on the left of the Union line were troops under the command of Major General Daniel E. Sickles of New York. Despite his lack of military schooling, Sickles was brave, audacious, and had proven himself to be an adequate brigade commander. In 1863 he was given command of the Third Corps, which he led at the Battle of Chancellorsville, Virginia. Sickles's corps had fought well but were ordered into a position that had a great disadvantage in ground height. As a result, Confederate artillery had pounded his troops without mercy. On the morning of July 2, Sickles was worried that the same situation was about to occur. Arriving at Gettysburg overnight of July 1, his troops had been ordered to occupy the southern end of Cemetery Ridge to Little Round Top. From his position the general worried that the ridge on which ran the Emmitsburg Road would be advantageous to the Confederates if they held it. Sickles sent several messengers to headquarters that morning requesting that General Meade visit the Third Corps line to discuss the situation. Meade declined while engaged in other duties. Certain of a Confederate threat to his front, Sickles finally sent out a strong scouting party that included a regiment of United States Sharpshooters. Entering Pitzer's Woods on Seminary Ridge, the sharpshooters encountered Confederate forces from A.P. Hill's Corps and a brisk fight ensued. Returning to the Union line, the scouts reported that the woods ahead of Sickles were full of Rebel soldiers and a dust cloud was seen, obviously caused by a strong column of Confederate troops headed his way. Believing that the Confederate attack would fall on him from the west, Sickles ordered his corps to advance from Cemetery Ridge and occupy the high ground at the Emmitsburg Road.

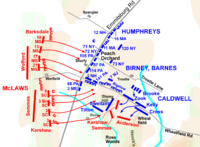

The Third Corps was greatly under strength. Sickles had only two divisions, instead of the customary three, under Maj. General David Birney and Brig. General A.A. Humphreys. As a precaution to cover his left flank, Birney's division was stretched from the Peach Orchard southeast to Devil's Den. Humphrey's brigades were arrayed in a battle line with supporting columns ready to march up to the Emmitsburg Road. Though this new line occupied some high ground, it was also very weak; there was not an adequate number of soldiers to man a solid line, especially on General Birney's front, and the advanced position presented the Confederates with a choice target to fire upon from two directions. Sickles had moved away from the main Union line on Cemetery Ridge losing the advantage of artillery support within a shortened front, and, perhaps most condemning, he had made the move forward in defiance of orders to stay where his corps had been posted. This opened a wide gap on both of his flanks, susceptible to being crushed by a flank attack- exactly what was about to happen courtesy of James Longstreet.

Longstreet's attack finally began at 4 o'clock when Confederate cannoneers opened fire on Union positions at Devil's Den and in the Peach Orchard. General Meade had visited Sickles' headquarters a few moments before and the two were conferring in the Peach Orchard when the Confederate guns opened fire. Despite the precarious position he was now in, Meade ordered Sickles to stay and fight along this new line and that other troops would be sent to assist.

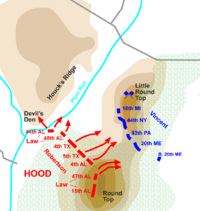

General Hood's Division was the first sent into the attack though the lanky general was unhappy with his assignment. The open farm fields allowed Union artillery and sharpshooters to pepper his troops long before they reached the opponent's lines. Hood approached General Longstreet, expressing several objections to the assignment given him and petitioned the general for permission to withdraw his troops to move around Big Round Top. The corps commander blunted Hood's argument. Lee's orders had to be followed and Hood had to continue the attack despite his objections. "Do your best, Sam," Longstreet told the obstinate Texan as he turned his horse away. Law's Alabama Brigade stepped off from Warfield Ridge toward Devil's Den and the Round Tops, closely followed by Brig. General George Anderson's Brigade. Next to Law's men marched the famous Texas Brigade commanded by Brig. General Jerome B. Robertson. This was General Hood's old brigade and he paid special attention to them. Riding to the front of his old command, Hood addressed his soldiers: "Fix bayonets, my brave Texans; forward and take those heights!" Minutes later, General Hood was carried from the battlefield with a horrendous injury to his left arm. Brig. General Evander Law immediately took command as the troops wrestled their way around Sickles' left flank at Devil's Den. The Confederates swung eastward through plowed fields and pastures filled with boulders, past broken fences, and headlong toward Union cannon posted on the ridge above the den, supported by Union infantry. Fighting erupted on the slopes of Little Round Top, in the Wheatfield, and at the Peach Orchard.

Little Round Top[edit]

"Little Round Top" was perhaps the single most important strategic position in the entire Civil War. Its elevation was 150 feet from the valley, and it had a rocky formation that limited its accessibility. From the top of this knob an army could punish the enemy soldiers below and successfully defend the entire flank. Unlike Big Round Top, there were no trees in the way on Little Round Top, as they had been all chopped down months earlier. If the Confederates had been able to seize this hill, then they would have routed the left flank of the Union Army, and then won Gettysburg and perhaps even the entire war.[7]

But it was not to be. Reacting to the initial Confederate charge, General Gouverneur K. Warren, Meade's chief engineer, was able to divert Colonel Strong Vincent's Union brigade to the slopes of Little Round Top. Understanding the importance of the hill, Vincent posted his regiments on the southern slope where they repulsed the first Confederate attacks. The southern regiments re-organized and renewed their efforts to drive Vincent's men from the hillside with repeated attacks. Vincent's line did not waver, however, and the Union men tenaciously held their ground. Vincent's left regiment, the 20th Maine Infantry under Colonel Joshua L. Chamberlain, held off the 15th Alabama Infantry for over an hour despite repeated attempts to get behind the Maine regiment and around its flank. With his regiment having lost heavily and ammunition nearly exhausted, Colonel Chamberlain decided to make a bayonet charge when the next attack came. The exhausted Alabamians were stopped in their tracks when a line of yelling, cursing men came down the slope at them with bayonets gleaming in the fading light. It was enough for many who threw down their arms. Others ran for their lives back into the woods of Big Round Top, which had less strategic significance. Chamberlain approached a Confederate officer whose pistol misfired in the colonel's face, and accepted the officer's sword in surrender.

While the 20th Maine was completing its action in the woods, Vincent's right regiment, the 16th Michigan Infantry, suddenly began to waver and give way. Screaming the "Rebel Yell", Confederates of the 4th and 5th Texas Infantry rushed up the slope in one final frenzy of shooting, stabbing, and clubbing. Racing to stem the flow of retreating soldiers, Colonel Vincent was in the act of rallying his soldiers when he was struck down by a southern bullet. At this critical moment Union reinforcements spearheaded by the 140th New York Infantry, arrived and halted the southern attack. Bravery and gallantry had saved Little Round Top, a key feature on the southern end of the Union line, but at a terrible cost in officers and men for both sides.

As the fighting raged at Little Round Top and around Devil's Den, Union troops in the Wheatfield came under attack first from G.T. Anderson's Georgia Brigade, followed soon after by the South Carolina Brigade of Brig. General Joseph Kershaw. Having left the protection of stone walls on Seminary Ridge, Kershaw's troops crossed the Emmitsburg Road dogged the entire way by Union cannon stationed in the Peach Orchard. Passing into the Rose Farm, Kershaw realized that his men would have to face two separate lines of Union infantry, one at the Peach Orchard and the other placed on a stone-covered hill adjacent to the Wheatfield. Forced to split his brigade in half, the general's left regiments moved against the orchard as his right marched toward the stony hill. Just behind Kershaw, the brigade of Brig. General Paul Semmes arrived and rushed to support the South Carolinian's attack. The fighting swirled through the woods surrounding the field as Anderson's troops probed and moved to outflank the Union forces under Generals DeTrobriand and Barnes. Kershaw's Confederates sought to split the Union defenders who, though outnumbered, fought back furiously.

Reinforcements from the Union Second Corps arrived, including the famous "Irish Brigade" led at Gettysburg by Colonel Patrick Kelly. The total number of Irishmen barely amounted to 500 officers and men. Before the brigade marched to the Wheatfield, Father William Corby stood upon a large boulder and granted the soldiers complete absolution at this time of crisis. The New York regiments unfurled their unique green silk flags bearing a golden harp and shamrocks and followed them southward. Kelly's soldiers were sent into the center of the "whirlpool", charging through the Wheatfield and into the woods on the west side where they threw back Kershaw's South Carolinians. One soldier recalled finding hundreds of dead and wounded soldiers amongst the rocks and called out to the unhurt Confederates to throw down their rifles and come forward. Several did, preferring capture to certain death.

The Valley of Death[edit]

The Second Corps troops were able to clear the Wheatfield of southerners, but only for a brief moment. The arrival of a fresh Confederate brigade of Georgia troops commanded by Brig. General William Wofford, which had just smashed in the last Union defenders at the Peach Orchard, drove into the woods outflanking the Union positions. The line melted before the Confederate onslaught. Wofford's regiment swept the Wheatfield and aided by men from Kershaw's, Semmes, and Anderson's brigades, smashed into the division of U.S. Regulars commanded by General Romeyn Ayres, the last Union soldiers who could stem the southern tide. Standing their ground, the Regulars suffered terrible casualties when Confederates were able to sweep around the Union soldiers before they began a fighting retreat across what became known as the "Valley of Death". Wofford's men raced on to the northern base of Little Round Top where they were suddenly counterattacked by a brigade of "Pennsylvania Reserves". Led in the attack by General Samuel Crawford, the Pennsylvanians forced Wofford's men back across the Valley of Death and into the Wheatfield itself. Just before the fighting ended in this area, it had reached a crescendo in the Peach Orchard and along the Union line north of it.

The Peach Orchard[edit]

From his headquarters at the Trostle Farm, General Sickles attempted to control the flow of the battle while shifting troops to shore up his battered left. At the height of the battle the general was struck in the leg by a cannonball and carried from the field on a stretcher. Despite the tremendous pain and shock, Sickles cheered on other soldiers hurrying to the front. He was taken to a field hospital where his shattered limb was removed that night. Command of the corps now fell upon General Birney, who knew that the situation was nearly hopeless. Union artillery at the Peach Orchard persisted in blasting back every Confederate assault, despite a relentless volume of Confederate iron thrown at them from guns on Seminary Ridge. Hapless infantrymen could only hug the ground as the missiles filled the air. At approximately 6:30, McLaws sent forward his Mississippi brigade commanded by Brig. General William Barksdale. The battered Union line collapsed when Barksdale's soldiers rammed through the Peach Orchard, flanking out Union regiments along the Emmitsburg Road. Barksdale was followed by Brig. General Wofford's Georgia brigade, which swept on to the Wheatfield, finally clearing it of Union troops. Supported by more southern brigades from Maj. General Richard Anderson's Division of Hill's Corps, Barksdale's men charged on, capturing cannon and shooting down Yankees who dared to make a stand. Before them was a sizable gap in the Union line between Cemetery Hill and Little Round Top, held by only a handful of Union batteries and one regiment of Union infantry. Barksdale's men, joined by two brigades from General Hill's Corps, stormed toward the gap.

On Cemetery Ridge, the 1st Minnesota Infantry was assigned to support a battery of Union guns when they were ordered to make a desperate charge. Without wavering or questioning the order, Colonel William Colvill led 262 of his men headlong into Brig. General Cadmus Wilcox's Alabama Brigade, halting them just long enough for more Union troops to arrive and fill the gap. Adjacent to Wilcox rushed Perry's Florida Brigade, commanded at Gettysburg by Colonel David Lang. Lang attempted to counter the Minnesotans charge but was in turn ambushed by another Union regiment that fired into the Floridians' flank, driving them into Wilcox's units. A brisk Union counterattack by a brigade of New York troops under Colonel George L. Willard that drove back Barksdale now turned on Wilcox and Lang. In danger of being flanked and possibly cut off, Wilcox ordered the two brigades to retreat, leaving scores of dead and wounded in the path of the charge. An additional Confederate brigade that threatened the Union line right up to its center was also thrown back, and the sounds of battle slowly died away with the sunset. Darkness put a grateful end to the slaughter and Meade used the lull to shore up the Union left with troops from the First, Fifth, and newly arrived Sixth Corps. What was left of Sickles' corps was consolidated with other units on Cemetery Ridge and the Union line re-established where it had been approximately seven hours before.

Culp's Hill[edit]

Delayed by Union artillery and poor communications, the other wing of Lee's army under General Ewell began the charge onto Culp's Hill at dusk. Confederate infantrymen under General Edward Johnson marched from the Hanover Road to Rock Creek at the base of Culp's Hill. Overwhelming Union artillery fire from Cemetery Hill had delayed the attack and Johnson found that the ground he had to cross to reach Culp's Hill broke up his formations, causing more delays to stop and reorganize before they reached Rock Creek at the base of the hill. In the gathering darkness, Johnson's men waded Rock Creek and pushed into deep woods where they encountered Union troops under Brig. General George S. Greene. During the afternoon, most of the Twelfth Corps had been sent from the hill toward the Round Tops to support Sickles' Corps, leaving Greene's troops to hold the hill. Stationed behind defenses constructed of logs, rocks, and earth, Greene's single brigade of New York regiments was stretched southward from the summit of Culp's Hill to a small knoll above Spangler's Spring. Johnson's brigades attacked the summit but reeled back under a never ending stream of Union bullets. Farther south, two regiments of Brig. General George Steuart's Brigade drove back Union skirmishers to find the Union earthworks on the knoll above Spangler's Spring abandoned.

Steuart attempted to press his units forward but halted when small arms fire hit his regiments from the summit of the hill and from the woods west of their newly won position. No matter in what direction the general sent his regiments, they were met with a blinding flash of musketry and forced back to the captured earthworks and stone wall that ran over the hill. "Our loss was heavy, " General Steuart reported, "the fire being terrific and in part a cross-fire." In the darkness, General Johnson could not determine his objectives and was uncertain of the force arrayed before him. The determined defense of Greene's men led Johnson to believe that he was heavily outnumbered. After communicating with General Ewell, he halted his attack at 11 PM and waited for reinforcements to arrive before renewing the assault at dawn. Though outnumbered almost three to one, Greene's men skillfully held their positions and fought back small probing parties of Confederates throughout the night. Additional Union regiments later arrived to support Greene and the echoes of rifle shots finally died away as both sides attempted to get a fitful few hours of rest before the battle would be renewed.

Northwest of Culp's Hill, two Confederate brigades from General Jubal Early's Division momentarily penetrated the Union defenses at Cemetery Hill. After dusk, Colonel Isaac Avery's North Carolina Brigade and Brigadier General Harry Hays' Louisiana Brigade, known as the "Louisiana Tigers", charged across the rolling Culp Farm and struck the Union positions at the base of the hill. The nickname for Hays' men came from former members of the original Louisiana Tigers or Wheat's Battalion, raised in 1861 but disbanded after Major Robert Wheat's death. The remaining Tigers were transferred into the various regiments of Hays' command where the other Louisiana soldiers had taken a liking to the nickname and the fame attached to it.

Union artillery sent shrapnel and canister at the dark columns approaching the hill. Soldiers fell in the corn and wheat, including Colonel Avery who was mortally wounded. Unable to speak, Avery handed an aide a last message: "Tell my father I died with my face to the enemy." The northern fire grew in intensity as the southerners got closer to the base of the hill where shaken Union regiments from the Eleventh Corps stood poised to resist the attack. Undaunted, the southerners rushed the Union line where the 5th, 6th, and 7th Louisiana Regiments overpowered and routed several Union regiments. Pouring through the gap, the Confederates rushed to the summit of Cemetery Hill and into the Union batteries stationed there. Though many of the infantrymen scattered, the Yankee artillerymen stuck to their guns defending them with rammers, trail spikes, pistols, and rocks taken from the nearby stone walls.

Cemetery Hill[edit]

Not quite a quarter mile away, Colonel Samuel Carroll's brigade of the Second Corps was massed behind Cemetery Ridge when an officer approached with orders from General Hancock: move immediately to the assistance of the Eleventh Corps on Cemetery Hill. Carroll marched his brigade across farm fields and the Taneytown Road, and through cemetery where they stumbled into a scene that one officer compared to "a swarm of mad bees around the hive..." Carroll, "found the enemy up to and in among the front guns of the batteries on the road. It being perfectly dark, and with no guide, I had to find the enemy's line entirely by their fire." Carroll's three regiments attacked, wading into the mass of milling soldiers, breaking up the already disordered Confederate formations. An intense hand-to-hand battle over the Union guns began. The 6th North Carolina Infantry had planted their regimental flag on one battery but were thrown back by a vicious bayonet charge of Carroll's command. Several regiments from General Coster's Brigade of the Eleventh Corps joined in the counterattack and by 10:30, the last Confederates had been thrown off Cemetery Hill. By midnight, the Union line was restored.

While evaluating his army's gains at day's end, a disappointed Lee realized that his gamble of attacking the Union flanks simultaneously had not paid off. Longstreet's command had taken some high ground but his losses were very heavy and Meade still held along Cemetery Ridge. The capture of Culp's Hill was still in doubt, though if it could be secured in the morning, the Union position on Cemetery Hill and the Baltimore Pike would be threatened. Determined to strike Meade's flank again with as much force as possible the following day, Lee consented to Johnson being re-enforced and for the attack to continue at first light. By that time he would be able to make a better evaluation of his chances for success in another attack on the Union flanks or devise another strategy.

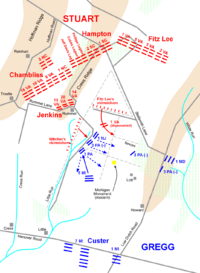

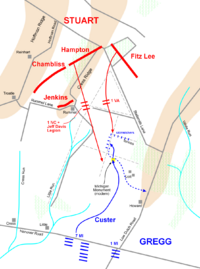

Late that evening, the general had a surprise visitor. General JEB Stuart arrived at Lee's headquarters to report on his success in riding behind the Yankee army and the capture of Federal wagons and stores. Instead of a warm welcome, Stuart received a cutting reprimand from Lee, upset with the cavalry commander who had not kept him informed of his movements or the position of the Union army during the past week. A shocked and embarrassed Stuart attempted to explain, but it had no effect on the old general. Lee's temper finally cooled. "I need you to help me fight these people," he reminded Stuart, before he changed the subject to his cavalry chief's assignment for the morrow.

General Meade spent the early evening shoring up his line by shifting troops to threatened areas, including Culp's Hill. It was imperative that the Twelfth Corps be returned to Culp's Hill to reinforce Greene's New Yorkers and drive out the threat to his rear at first light. Little did the Confederates who occupied the Union earthworks at Culp's Hill realize that they were only several hundred yards from the Baltimore Pike, the main route of communication and supply to the Union Army positions. Meade appreciated this fact and knew that measures had to be taken to block the Confederate opportunity as soon as possible.

Yet there were many issues on the general's mind that evening when he called his generals together for a "Council of War" held at army headquarters in the home of widow Lydia Leister on the Taneytown Road. The tiny house had two rooms, one of which was soon crowded with Meade's corps commanders, weary and dirty after the long day. The generals spoke frankly about the battle so far and discussed the Union positions on Cemetery Ridge. Different viewpoints were shared until the central question was placed before the group: Should the Army of the Potomac defend their current position for another day or attack? Almost to a man, the officers agreed to stay at Gettysburg and wait for Lee to attack. If he did not, then Meade should order a counterattack and force Lee to fight or flee. The Gettysburg Campaign was about to reach its climax.

The Third Day[edit]

Sunset of July 2 found the Army of the Potomac arrayed in a fishhook-shaped line anchored solidly along Cemetery Ridge, from Big and Little Round Top to Culp's Hill, the most threatened part of the Union line that evening. Based on the consensus of officers who attended the Council of War at Meade's headquarters, the Confederate foothold at Culp's Hill had to be driven off to secure the Union right flank, which covered the Baltimore Pike, the all important road into the Union rear. General Henry Slocum issued orders for his Twelfth Corps troops to return to Culp's Hill and retake the sections occupied by General Johnson's Confederate Division as early as possible.

Preparations for the attack were completed and at 4 AM, the Twelfth Corps counterattacked Johnson's men just as they were preparing to make their own attempt to storm Culp's Hill. Union artillery posted on the Baltimore Pike and Powers Hill blasted southern regiments that ventured out of the captured works or pinned them down so that movement was nearly impossible. Brig. General Alpheus S. Williams, who was placed in command of the corps by Slocum, sent his regiments into the fighting in waves. Each attack countered every move made by Johnson's men, pinning them into a tight area above Spangler's Spring and at the base of the hill proper. For six hours the battle on the hillside raged. The volume of musketry was ear-splitting and the carnage appalling, especially in the meadow near Spangler's Spring. A misunderstanding of verbal orders caused the 2nd Massachusetts Infantry and 27th Indiana Infantry to charge across the open meadow where they were caught in a cross fire from Confederates stationed behind stone walls and earthworks. Both regiments were decimated in the attack. The survivors staggered back to their starting point in the woods south of the field, now littered with the dead and wounded. Soon after this charge, an attempt was made by the 2nd Maryland Infantry (CSA) and 3rd North Carolina Infantry to break out of the Union entrapment. The result was as dismal as the Union attempt had been, the Marylanders suffering heavy casualties in their charge through a small field known today as "Pardee Field", named for Colonel Ario Pardee of the 147th Pennsylvania Infantry whose troops opposed the southern attack.

The Twelfth Corps had advantages over Johnson's southerners in holding fortified positions on the higher portions of the hill, more men and regiments were available to relieve those in the front line, and Union artillery that provided accurate support to Williams' soldiers. Despite their hold on the hill above Spangler's Meadow, Johnson's men could not make any headway through the strong Union defenses and had no artillery to support the attack. By 10 o'clock that morning, General Johnson realized that he could not break through or capture Culp's Hill and began to systematically withdraw his troops, being careful not to give the Union any advantages in counterattacking his retreat. General Steuart, whose brigade of Maryland and North Carolina troops had held the hill above Spangler's Meadow, was so distraught by his losses that he broke into tears. "My poor boys," he said, wringing his hands as he watched his exhausted and bloodied men march by, "My poor boys!"

Union regiments re-took the abandoned positions soon after and General Geary reported that the rebels had gone from his front. The point of the fishhook was no longer in southern hands.

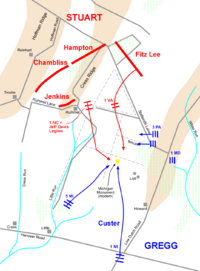

General Lee had hoped to again force the Union flanks in the early morning hours. To coincide with his attacks, he had ordered his cavalry chief, JEB Stuart, to ride around the right of the Union positions and strike toward Meade's supply line. This disruption would threaten Union supply lines and communications, forcing Meade to withdraw troops to protect his threatened rear. But delays and the Union counter-attack that resulted in the defeat of Johnson's command at Culp's Hill, forced a dramatic change in plans. The loss of Culp's Hill left him with few options. Determined to strike again as soon as possible, Lee threw in his trump card: a grand assault against the enemy center preceded by a massive artillery bombardment. Believing that Meade had weakened his center to reinforce his flanks, Lee stated that a bold stroke on the Union center would break the weakest part of the fishhook. The charge would include troops from two corps- an estimated 18,000 men, preceded by a massive bombardment that would sweep the few Union batteries from this section of the Union line.

The last gamble[edit]

General Lee studied the Union line that morning and presented his plan. General Longstreet was assigned overall command of the attack and ordered to execute the charge. Freshly arrived on the field, Maj. General George Pickett's Division of Virginia troops would form the right half of the attacking column with two divisions from A.P. Hill's Corps to form the left half. If all went well, the attack would be carried out before noon though assembling the required number of men and artillery was another matter. Due to heavy losses suffered on July 1, Hill's six brigades committed to the assault could only muster about 6,000 men. Combined with the 5,500 under Pickett's command and 1,600 men from Anderson's Division of Hill's Corps, barely two-thirds of the desired strength was available. By mid-morning, two of Pickett's brigades were lying in a shallow depression north of the Spangler Farm with the third just behind at the edge of Spangler Woods. Troops from Hill's corps were arrayed in battle lines behind the trees on Seminary Ridge. Inevitable delays held up the attack and by noon an eerie silence had descended on the field, broken only by scattered rifle shots of sharpshooters between Gettysburg and Cemetery Hill. Another hour would pass before all of the preparations were complete.

Late on the morning of July 3, Union General Henry Hunt rode to the crest of Cemetery Ridge. "Here a magnificent display greeted my eyes," he wrote. "Our whole front for two miles was covered by batteries already in line or going into position. They stretched... from opposite the town to the Peach Orchard, which bounded the view to the left, the ridges of which were thick with cannon. Never before had such a sight been witnessed on this continent. What did it mean?"

Little did Hunt know that this line of approximately 120 cannon was arranged by General Longstreet to prepare for the greatest charge of the war. In command of the center of the artillery line was 28 year-old Colonel Edward P. Alexander, who's overwhelming duty was to direct his artillery battalion and judge the effect of the artillery barrage on the enemy line. Alexander later wrote that his guns were in a "splendid position" to strike Cemetery Ridge, though his primary concern was for ammunition. The southern artillery had to achieve good results within the first half-hour for them to properly support the infantry assault and would require a fresh supply as soon as the infantry advanced. Alexander's commander, Colonel James Walton, ordered the supply train brought forward to a location near the front lines so that empty ammunition chests could be quickly replenished.

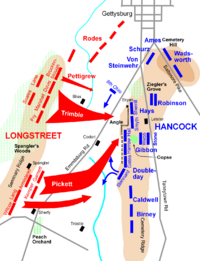

Pickett's Charge[edit]

It was just before 1 PM when General Longstreet sent orders to the Washington Artillery of New Orleans, stationed in the Peach Orchard, to fire the signal shots to begin the bombardment. The afternoon calm was broken by two loud booms followed by a violent, simultaneous blast of fire from the solid line of Confederate cannon. Surprised Union artillerymen ran to their cannon and returned fire. The battlefield shook under the weight of explosions. Fire and dense smoke covered the ridges and rolled across the fields. Gunners toiled over their heated guns as shells churned up the earth around them, knocking men and horses to the ground. Caissons and limber chests of two Union batteries erupted in massive explosions. Alexander anxiously watched the Yankee line through binoculars. It appeared that nothing could live under the weight of the bombardment on that narrow ridge, but the Union gunfire did not subside; these determined Union cannoneers simply would not quit. Alexander's fears were proving true; the Confederate guns were not doing as much damage as he had hoped in the initial attack and with the high rate of fire necessary to suppress the Union artillery, his ammunition chests would quickly be depleted. Adding to the problem was the poor quality of some southern-made artillery fuses and shells, many of which failed to explode. Inexperienced gunners in several batteries had difficulty aiming their cannon properly and many shells sailed over Cemetery Ridge into the Union rear, doing little damage to the front line troops and guns. The bombardment continued toward its second hour when ammunition chests began to empty. Artillery drivers took their caissons to the site where wagons loaded with extra ammunition were located, only to find them gone. General William N. Pendleton, Lee's artillery chief, had ordered the wagons away for their protection and not bothered to tell Alexander or any of his subordinates where they had been sent. Staff officers rode off to search for the wayward supply wagons as Alexander's gunners began to empty the last level of artillery shells in the limber chests.

General Hunt, who had earlier remarked on the impressive display of Confederate ordnance, had also prepared the Union artillery line that morning by insuring fresh batteries could be sent forward from the Artillery Reserve when needed. When his active batteries ran low on ammunition, Hunt could replace them with new units from the reserve. After forty minutes of constant shelling, those batteries near the center of the line were low on long range ammunition or partially disabled. Hunt ordered those gunners to cease fire and sent couriers to bring fresh batteries forward. The Union fire slackened as the guns went silent. Artillerymen in several batteries limbered their smoking guns and prepared to leave, yet many could not- the tremendous barrage had killed or maimed most of the horses, which lay in heaps in front of the limbers and caissons still strapped into their harnesses. Through the dense battle smoke, Alexander observed several Union batteries withdraw and immediately sent a note to General Pickett: "Come quick. The guns in the cemetery have gone. Come quick or I cannot properly support you." Pickett immediately reported to General Longstreet in Spangler's Woods and presented Alexander's note. Seated on a fence at the edge of the woods, Longstreet silently read the note without uttering a word. "Shall I advance, sir?" Pickett asked. The sullen general could barely nod his approval. Racing to his horse, Pickett mounted and wisped a hasty salute before turning to ride to his troops. Longstreet remained on his fence quiet and dour, his eyes downcast while his troops moved into position to begin the mile long march to Cemetery Ridge.

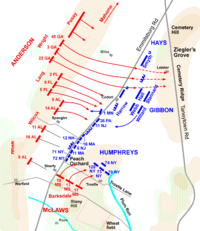

General George Edward Pickett's Division was composed of three brigades of Virginia regiments. Brig. General Richard Garnett and Brig. General James Kemper led the two brigades arranged in the first line, with the third brigade, commanded by Brig. General Lewis Armistead, just behind. Lt. J. Irving Sale of Company H, 53rd Virginia Infantry, recalled General Armistead standing at the front of his old regiment. "Just before we started," wrote Lt. Sale, "he tore off his cravat, put his hat on his sword, and cried: 'Remember your homes, your wives and your sweethearts!'" There were similar addresses by officers of other regiments, yet the most inspiring words may have come from General Pickett himself who called on his men to remember their homes, "wives and sweethearts", and the importance of being a native of Virginia. With that, the advance began, the long columns tramping steadily forward in almost perfect alignment past the Emmitsburg Road and across open farm land toward the smoldering Union line on Cemetery Ridge.

Almost immediately, Union artillery from Cemetery Hill to Little Round Top opened fire, sending sold shot and shell into the thick, gray-clad columns.

North of Pickett's Division, three lines of southern infantry emerged from the woods on Seminary Ridge and quickly advanced through the William Bliss Farm, past the smoking remains of the house and barn which had been burned that morning. The regular commanders of both divisions having been wounded, Brig. General James J. Pettigrew led Heth's Division, and Maj. General Isaac Trimble led a portion of Pender's Division. The troops marched in perfect alignment until Union shells hit the left flank of the line where Colonel John Brockenbrough's small Virginia brigade marched. Nearly shattered on the first day of the battle, Brockenbrough's men could not stand the fire and fled. General Trimble quickly ordered his two brigades to the left to bolster the wavering line while Pettigrew continued to urge his men forward.

The Union center was held by the Second Corps commanded on July 3 by General John Gibbon, the same officer who Meade had warned about an attack on his front the night before. Gibbon realized what this bombardment meant and had done all he could to prepare his infantry who suffered under the barrage. Many a veteran complained of the frustration of being unable to fight back against an enemy at long range. Some even expressed a sense of relief to finally see the Confederate infantry emerge from the woods and fields to begin their charge. At last they would have their chance to fight back.

At the center of Gibbon's line, referred to as "the Angle" for the sharp corner of the stone fence located there, was an infantry brigade of regiments raised entirely within the county limits and city of Philadelphia. The "Philadelphia Brigade" had fought with distinction during the Peninsular Campaign, Antietam, and Fredericksburg. Now, they were witnesses to the greatest charge of the war and would soon find themselves at its center, commanded by an officer unfamiliar to a majority of them.