White Rose

From Nwe

From Nwe The White Rose (German: die Weiße Rose) was a non-violent resistance group in Nazi Germany, consisting of a number of students from the University of Munich and their philosophy professor. The group became known for an anonymous leaflet campaign, lasting from June 1942 until February 1943, that called for active opposition to German dictator Adolf Hitler's regime.

The six core members of the group were arrested by the Gestapo, convicted and executed by beheading in 1943. The text of their sixth leaflet was smuggled out of Germany through Scandinavia to the United Kingdom, and in July 1943, copies of it were dropped over Germany by Allied planes.

Today, the members of the White Rose are honored in Germany as some of its greatest heroes because they opposed the Third Reich in the face of almost certain death.

Members

Isn’t it true that every honest German is ashamed of his government these days? Who among us can imagine the degree of shame that will come upon us and our children when the veil falls from our faces and the awful crimes that infinitely exceed any human measure are exposed to the light of day? (the first leaflet of the White Rose)[1]

The core of the White Rose comprised students from the university in Munich–Sophie Scholl, her brother Hans Scholl, Alex Schmorell, Willi Graf, Christoph Probst, Traute Lafrenz, Katharina Schueddekopf, Lieselotte (Lilo) Berndl, and Falk Harnack. Most were in their early twenties. A professor of philosophy and musicology, Kurt Huber, also associated with their cause. Additionally, Wilhelm Geyer, Manfred Eickemeyer, Josef Soehngen, and Harald Dohrn participated in their debates. Geyer taught Alexander Schmorell how to make the tin templates used in the graffiti campaign. Eugen Grimminger of Stuttgart funded their operations. Grimminger's secretary Tilly Hahn contributed her own funds to the cause, and acted as go-between between Grimminger and the group in Munich. She frequently carried supplies such as envelopes, paper, and an additional duplicating machine from Stuttgart to Munich.

Between June 1942 and February 1943, they prepared and distributed six leaflets, in which they called for the active opposition of the German people to Nazi oppression and tyranny. Huber wrote the final leaflet. A draft of a seventh leaflet, written by Christoph Probst, was found in the possession of Hans Scholl at the time of his arrest by the Gestapo. While Sophie Scholl hid incriminating evidence on her person before being taken into custody, Hans did not do the same with Probst's leaflet draft or cigarette coupons given him by Geyer, an irresponsible act that cost Christoph his life and nearly undid Geyer.

The White Rose was influenced by the German Youth Movement, of which Christoph Probst was a member. Hans Scholl was a member of the Hitler Youth until 1937 and Sophie was a member of the Bund Deutscher Mädel. Membership of both groups was compulsory for young Germans, although many such as Willi Graf, Otl Aicher, and Heinz Brenner never joined. The ideas of dj 1.11. had strong influence on Hans Scholl and his colleagues. d.j.1.11 was a youth group of the German Youth Movement, founded by Eberhard Koebel in 1929. Willi Graf was a member of Neudeutschland, a Catholic youth association, and the Grauer Orden.

The group was motivated by ethical and moral considerations. They came from various religious backgrounds. Willi and Katharina were devout Catholics. The Scholls, Lilo, and Falk were just as devoutly Lutheran. Traute adhered to the concepts of anthroposophy, while Eugen Grimminger considered himself Buddhist. Christoph Probst was baptized Catholic shortly before his execution, but he followed his father's theistic beliefs.

Some had witnessed the atrocities of the war on the battlefield and against the civilian population in the East. Willi Graf alone saw the Warsaw and Lodz Ghettos, and could not get the images of bestiality out of his mind. By February 1943, the friends in Munich sensed that the reversal of fortune that the Wehrmacht suffered at Stalingrad would eventually lead to Germany's defeat. They rejected fascism and militarism and believed in a federated Europe that adhered to principles of tolerance and justice.

Origin

In 1941, Sophie and Hans Scholl attended the sermon of an outspoken critic of the Nazi regime, Bishop August von Galen, decrying the euthanasia policies (extended that same year to the concentration camps)[2] which the Nazis maintained would protect the European gene pool.[3] Horrified by the Nazi policies, Sophie obtained permission to reprint the sermon and distribute at the University of Munich as the group's first pamphlet prior to their formal organization.[3]

Under Gestapo interrogation, Hans Scholl said that the name the White Rose had been taken from a Spanish novel he had read. Annette Dumbach and Jud Newborn speculate that this may have been The White Rose, a novel about peasant exploitation in Mexico published in Berlin in 1931, written by B. Traven, the German author of The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. Dumbach and Newborn say there is a chance that Hans Scholl and Alex Schmorell had read this. They write that the symbol of the white rose was intended to represent purity and innocence in the face of evil.[4]

Leaflets

Quoting extensively from the Bible, Aristotle and Novalis, as well as Goethe and Schiller, they appealed to what they considered the German intelligentsia, believing that they would be intrinsically opposed to Nazism. At first, the leaflets were sent out in mailings from cities in Bavaria and Austria, since the members believed that southern Germany would be more receptive to their anti-militarist message.

Since the conquest of Poland three hundred thousand Jews have been murdered in this country in the most bestial way … The German people slumber on in their dull, stupid sleep and encourage these fascist criminals … Each man wants to be exonerated of a guilt of this kind, each one continues on his way with the most placid, the calmest conscience. But he cannot be exonerated; he is guilty, guilty, guilty! (the second leaflet of the White Rose)[5]

Alexander Schmorell penned the words for which the White Rose has become best known. Most of the more practical material—the calls to arms and statistics of murder—came from Alex's pen. Hans Scholl wrote in a characteristically high style, exhorting the German people to action on the grounds of philosophy and reason.

At the end of July 1942, some of the male students in the group were deployed to the Eastern Front for military service (acting as medics) during the academic break. In late autumn, the men returned, and the White Rose resumed its resistance activities. In January 1943, using a hand-operated duplicating machine, the group is thought to have produced between 6,000 and 9,000 copies of their fifth leaflet, "Appeal to all Germans!" which was distributed via courier runs to many cities (where they were mailed). Copies appeared in Stuttgart, Cologne, Vienna, Freiburg, Chemnitz, Hamburg, Innsbruck, and Berlin. The fifth leaflet was composed by Hans Scholl with improvements by Huber. These leaflets warned that Hitler was leading Germany into the abyss; with the gathering might of the Allies, defeat was now certain. The reader was urged to "Support the resistance movement!" in the struggle for "Freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and protection of the individual citizen from the arbitrary action of criminal dictator-states." These were the principles that would form "the foundations of the new Europe."

The leaflets caused a sensation, and the Gestapo initiated an intensive search for the publishers.

On the nights of February 3, 8, and 15, 1943, the slogans "Freedom" and "Down with Hitler" appeared on the walls of the University and other buildings in Munich. Alexander Schmorell, Hans Scholl and Willi Graf had painted them with tar-based paint (similar graffiti that appeared in the surrounding area at this time was painted by imitators).

The shattering German defeat at Stalingrad at the beginning of February provided the occasion for the group's sixth leaflet, written by Huber. Headed "Fellow students," it announced that the "day of reckoning" had come for "the most contemptible tyrant our people has ever endured." As the German people had looked to university students to help break Napoleon in 1813, it now looked to them to break the Nazi terror. "The dead of Stalingrad adjure us!"

Capture and trial

On 18th February 1943, the same day that Nazi propaganda minister Josef Goebbels called on the German people to embrace total war in his Sportpalast speech, the Scholls brought a suitcase full of leaflets to the university. They hurriedly dropped stacks of copies in the empty corridors for students to find when they flooded out of lecture rooms. Leaving before the class break, the Scholls noticed that some copies remained in the suitcase and decided it would be a pity not to distribute them. They returned to the atrium and climbed the staircase to the top floor, and Sophie flung the last remaining leaflets into the air. This spontaneous action was observed by the custodian Jakob Schmid. The police were called and Hans and Sophie were taken into Gestapo custody. The other active members were soon arrested, and the group and everyone associated with them were brought in for interrogation.

The Scholls and Probst were the first to stand trial before the Volksgerichtshof—the People's Court that tried political offenses against the Nazi German state—on February 22, 1943. They were found guilty of treason and Roland Freisler, head judge of the court, sentenced them to death. The three were executed by guillotine. All three were noted for the courage with which they faced their deaths, particularly Sophie, who remained firm despite intense interrogation. (Reports that she arrived at the trial with a broken leg from torture are false.) Sophie told Freisler during the trial, "You know as well as we do that the war is lost. Why are you so cowardly that you won't admit it?" (Hanser, "A Noble Treason")

The second White Rose trial took place on April 19, 1943. Only eleven had been indicted before this trial. At the last minute, the prosecutor added Traute Lafrenz (who was considered so dangerous she was to have had a trial all to herself), Gisela Schertling, and Katharina Schueddekopf. None had an attorney. An attorney was assigned after the women appeared in court with their friends.

Professor Huber had counted on the good services of his friend, Justizrat Roder, a high-ranking Nazi. Roder had not bothered to visit Huber before the trial and had not read Huber's leaflet. Another attorney had carried out all the pre-trial paperwork. When Roder realized how damning the evidence was against Huber, he resigned. The junior attorney took over.

Grimminger initially was to receive the death sentence for funding their operations. His attorney successfully used the female wiles of Tilly Hahn to convince Freisler that Grimminger had not known how the money had been used. Grimminger escaped with only ten years penitentiary.

The third White Rose trial was to have take place on April 20, 1943 (Hitler's birthday), because they anticipated death sentences for Wilhelm Geyer, Harald Dohrn, Josef Soehngen, and Manfred Eickemeyer. Freisler didn't want too many death sentences at a single trial, so had scheduled those four men for the next day. However, the evidence against them was lost, so the trial was postponed until July 13, 1943.

At that trial, Gisela Schertling—who had betrayed most of the friends, even fringe members like Gerhard Feuerle—redeemed herself by recanting her testimony against all of them. Since Freisler did not preside over the third trial, the judge acquitted all but Soehngen (who only got six months in jail) for lack of evidence.

Alexander Schmorell and Kurt Huber were beheaded on July 13, 1943, and Willi Graf on October 12, 1943. Friends and colleagues of the White Rose, who helped in the preparation and distribution of leaflets and in collecting money for the widow and young children of Probst, were sentenced to prison terms ranging from six months to ten years.

Prior to their deaths, several members of the White Rose believed that their execution would stir university students and other anti-war citizens into activism against Hitler and the war. Accounts suggest, however, that university students continued their studies as usual, citizens mentioned nothing, many regarding the movement as anti-national. In fact, after the Scholl/Probst executions, students celebrated their deaths.

After her release for the sentence handed down on April 19, Traute Lafrenz was rearrested. She spent the last year of the war in prison. Trials kept being postponed, moved to different locations, because of Allied air raids. Her trial was finally set for April 1945, after which she surely would have been executed. Three days before trial, however, the Allies liberated the town where she was held prisoner, thereby saving her life.

The White Rose had the last word. Their last leaflet was smuggled to The Allies, who edited it, and air-dropped millions of copies over Germany. The members of the White Rose, especially Sophie, became icons of the new post-war Germany.

Legacy

Their final leaflet was retitled "The Manifesto of the Students of Munich" and dropped by Allied planes over Germany in July 1943.[6]

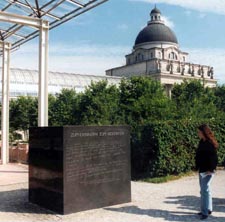

The square on which the central hall of Munich University is located has been named "Geschwister-Scholl-Platz" after Hans and Sophie Scholl; the square opposite to it, "Professor-Huber-Platz." There are two large fountains located in front of the university, one on either side of Ludwigstrasse. The fountain directly in front of the university is dedicated to Hans and Sophie Scholl and the other, across the street, is dedicated to Professor Huber. Many schools, streets, and other places all over Germany are named in memory of the members of the White Rose. The subject of the White Rose has also received many artistic treatments, including the acclaimed Die weiße Rose (opera) by composer Udo Zimmermann.

With the fall of Nazi Germany, the White Rose came to represent opposition to tyranny in the German psyche and was lauded for acting without interest in personal power or self-aggrandizement. Their story became so well-known that the composer Carl Orff claimed (though by some accounts [7], falsely) to his Allied interrogators that he was a founding member of the White Rose and was released. While he was personally acquainted with Huber, there is a lack of other evidence that Orff was involved in the movement.

In an extended German national TV competition held in the autumn of 2003 to choose "the ten greatest Germans of all time" (ZDF TV), Germans under the age of 40 catapulted Hans and Sophie Scholl of the White Rose to fourth place, selecting them over Bach, Goethe, Gutenberg, Willy Brandt, Bismarck, and Albert Einstein. Not long before, young women readers of the mass-circulation magazine "Brigitte" had voted Sophie Scholl to be "the greatest woman of the twentieth century."

Media representations

In February 2005, a movie about Sophie Scholl's last days, Sophie Scholl—Die letzten Tage (Sophie Scholl: The Final Days), featuring actress Julia Jentsch as Sophie, was released. Drawing on interviews with survivors and transcripts that had remained hidden in East German archives until 1990, it was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in January 2006. An English language film, The White Rose (film), was in development for a time in 2005/06, to be directed by Anjelica Huston and starring Christina Ricci as Sophie Scholl.

Prior to the Oscar-nominated film, there had been three earlier film accounts of the White Rose resistance. The first is a little known film that was financed by the Bavarian state government entitled Das Verspechen (The Promise) and released in the 1970s. The film is not well known outside Germany and, to some extent, even within Germany. The film was particularly notable in that unlike most other films about the White Rose, it showed the White Rose from its inception and how it progressed. In 1982, Percy Adlon's Fünf letzte Tage (The Last Five Days) presented Lena Stolze as Sophie in her last days from the point of view of her cellmate Else Gebel. In the same year, Stolze repeated the role in Michael Verhoeven's Die Weiße Rose (The White Rose).

The book Sophie Scholl and the White Rose was published in English in February 2006. This account by Annette Dumbach and Dr. Jud Newborn tells the story behind the film Sophie Scholl: The Final Days, focusing on the White Rose movement while setting the group's resistance in the broader context of German culture and politics and other forms of resistance during the Nazi era.

Lillian Garrett-Groag's play, The White Rose, premiered at the Old Globe Theatre in 1991.

In Fatherland, an alternate history novel by Robert Harris, there is passing reference to the White Rose's still remaining active in Nazi-ruled Germany in 1964.

In 2003, a group of college students at the University of Texas in Austin, Texas established The White Rose Society dedicated to Holocaust remembrance and genocide awareness. Every April, the White Rose Society hands out 10,000 white roses on campus, representing the approximate number of people killed in a single day at Auschwitz. The date corresponds with Yom Hashoah, Holocaust Memorial Day. The group organizes performances of The Rose of Treason, a play about the White Rose, and has rights to show the movie Sophie Scholl—Die letzten Tage (Sophie Scholl: The Final Days). The White Rose Society is affiliated with Hillel and the Anti-Defamation League.

The UK-based genocide prevention student network Aegis Students uses a white rose as their symbol in commemoration of the White Rose movement.

Notes

- ↑ www.deheap.com, Leaflets of the White Rose. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- ↑ Robert Jay Lifton, The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Shoah Education Web Project, The White Rose. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- ↑ Annette Dumbachand Jud Newborn, Sophie Scholl & The White Rose, Oneworld Publications. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- ↑ Jlrweb, Second leaflet, Leaflets of the White Rose. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- ↑ Psywar, "G.39, Ein deutsches Flugblatt," Aerial Propaganda Leaflet Database, twentieth World War. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- ↑ h-net, Dennis. Retrieved January 2, 2009.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- DeVita, James. The Silenced. HarperCollins, 2006. ISBN 9780060784645.

- Dumbach, Annette, and Jud Newborn. Sophie Scholl & The White Rose. Oneworld Publications, 2006. ISBN 9781851684748.

- Sachs, Ruth Hanna. White Rose History. Lehi, Utah: Exclamation! Publishers, 2002. ISBN 9780971054141.

- Sachs, Ruth. Alexander Schmorell: Gestapo Interrogation Transcripts. Marlton, NJ: Exclamation! Publishers, 2006. ISBN 9780976718383.

- Sachs, Ruth. The Bündische Trials (Scholl / Reden): 1937-1938.. Phoenixville, PA: Exclamation! Publishers, 2003. ISBN 9780971054127.

- Söhngen, Josef. Third White Rose Trial: July 13, 1943 (Eickemeyer, Söhngen, Dohrn, and Geyer). Phoenixville, PA: Exclamation! Publishers, 2003. ISBN 9780971054189.

External links

All links retrieved October 2, 2020.

- The White Rose: Information, links, discussion, etc.

- Wittenstein, George. Memories of the White Rose

- The White Rose: A Lesson in Dissent, Jewish Virtual Library.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 23:32:51 | 50 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/White_Rose | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF