Marianne Moore

From Nwe

From Nwe

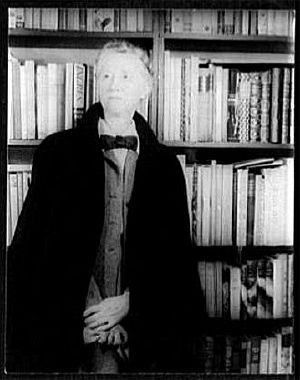

Marianne Moore (December 11, 1887 – February 5, 1972) was a Modernist American poet and writer. Moore's reputation has never been as wide-spread as that of many of her Modernist peers; she never achieved the infamy of Ezra Pound, the folk popularity of Robert Frost, or the scholarly renown of T.S. Eliot, though she corresponded with all of these individuals as well as virtually every major poet and author of the early twentieth century. Nevertheless, despite remaining relatively obscure, Moore has continued to gain acclaim in the decades since her death, with many noted poets and scholars, Elizabeth Bishop and William Carlos Williams among them, ranking her as one of the most successful poets in all of Modernism.

In part, Moore's delayed recognition is due to her idiosyncratic style. She was, and remains, one of the most difficult poets to categorize both in Modernism and in American poetry at large. She wrote primarily in a peculiar syllabic form of her own invention, concentrating on imagery rather than sound to create poems that resonate with the brevity and precision of haiku. Moore wrote in syllabic meter, which is to say that her lines are measured in syllables, not metrical feet, setting her apart from the entire Western tradition of measured poetry, while at the same time distinguishing her works from the completely undisciplined poetry of free verse.

Despite her idiosyncratic style, Moore's philosophy of poetry, perhaps best expressed in her poem appropriately titled "Poetry," shares a great deal with the Imagism of many of the key Modernist poets such as Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams. Like Williams and Pound, her poems concentrate on what she calls "the genuine": the microscopic details of life that, taken together, give the world meaning. As Moore calls it, the purpose of poetry is to construct "imaginary gardens with real toads in them"—to bring the realness of life into the world of the imagination—and this she does. Time and again, her poems take the smallest and strangest things; a steamroller, a coastline, a cat in an armchair—and bring the beauty of the genuine to our eyes.

Life and Work

Early Years

Marianne Moore was born in Kirkwood, Missouri, outside of St. Louis, daughter of a construction engineer and inventor, John Milton Moore, and his wife, Mary Warner. She grew up in the household of her grandfather, a Presbyterian pastor, her father having been committed to a mental hospital before her birth. In 1905, Moore entered Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania, and graduated four years later. She taught courses at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, until 1915, when Moore moved to New York and began to publish poetry professionally. In the years between her graduation from college and her move to New York, Moore also spent a number of years traveling abroad through Europe and, while there, she made the acquaintance of a number of major figures in Modernism who would later champion her work.

In Full Career

In part because of her extensive travels before the First World War, Moore came to the attention of poets as diverse as Wallace Stevens, William Carlos Williams, H.D., T. S. Eliot, and Ezra Pound. With H.D.'s help in particular, Moore was able to obtain much-needed employment in the publishing industry. From 1925 until 1929, Moore served as editor of the literary and cultural journal The Dial. Working for The Dial gave Moore a pivotal role in the American poetry scene; the journal was one of the leading publications for emerging poets, and as an editor, Moore would correspond with all the leading young poets of her times. Like Ezra Pound, Moore became a patron of poetry, encouraging promising poets including Elizabeth Bishop and Allen Ginsberg, and publishing their work, as well as corresponding with them in order to aid in the refinement of their technique.

Moore the Celebrity

Later in life, after having won a number of prizes (including the National Book Award and Pulitzer) for her Collected Poems of 1951, Moore became a minor celebrity in New York literary circles. She often served as unofficial hostess for the Mayor of New York. She attended boxing matches, baseball games and other public events, dressed in what became her signature garb: a tricorn hat and a black cape, giving her the look, as more than one onlooker suggested, of a woman straight from the Revolutionary War. Moore particularly liked athletics and athletes, and was a great admirer of Muhammad Ali, to whose spoken-word album, I Am the Greatest!, she wrote liner notes. Moore continued to publish poems in various journals, including The Nation, The New Republic, and Partisan Review, as well as publishing various books and collections of her poetry and criticism.

Edsel consulting

In 1955, in what is perhaps the most memorable episode of her life as a minor celebrity, Moore was informally invited by Ford's David Wallace, Manager of Marketing Research for Ford, for input and suggestions for naming the company's new project, an experimental car which would eventually become the infamous Ford Edsel. Wallace's rationale was "who better to understand the nature of words than a poet?"

Moore, a loyal Ford owner, submitted numerous names for the new vehicle, which included: "Silver Sword," "Thundercrest" (and "Thundercrester"), "Resilient Bullit," "Intelligent Whale," "Pastelogram," "Adante con Moto" "Varsity Stroke," and "Mongoose Civique." (One name she suggested, "Chaparral," later coincidentally was used for a racing car.) In a letter dated December 8th 1955, Moore wrote the following:

-

- Mr Young,

- May I submit UTOPIAN TURTLETOP? Do not trouble to answer unless you like it. Marianne Moore

All these outside ideas were rejected; although Miss Moore received two dozen roses and a thank you note affectionately addressed to the Top Turtletop. In her reply to Young she regretted that she could not have been more help, and noted that she was looking forward to trying out the vehicle when it was introduced.

Later years

Not long after throwing the first pitch for the 1968 season in Yankee Stadium, Moore suffered a stroke. She suffered a series of strokes thereafter, and died in 1972. She had never married. Moore's living room has been preserved in its original layout in the collections of the Rosenbach Museum & Library in Philadelphia. Her entire library, knicknacks (including a baseball signed by Mickey Mantle), all of her correspondence, photographs, and poetry drafts are available for public viewing.

Her most famous poem is perhaps the one entitled, appropriately, Poetry, in which she hopes for poets who can produce "imaginary gardens with real toads in them." It also expressed her idea that poetry is not just written in meter, but in more natural forms. The poem also affirms the sentiment that it is not valid "to discriminate against 'business-documents and / school-books': all these phenomena are important," a sentiment very similar to one expressed by William Carlos Williams, namely that poetry can be found in the newspaper and the telephone book, in the conversations one hears on the street and on the words of a billboard sign, just as well as it can be found in the works of Shakespeare. The poem is written in Moore's unusual syllabic style, where each stanza (loosely) replicates a pattern of repeated syllables:

-

- "Poetry"

I, too, dislike it: there are things that are important beyond

all this fiddle.

Reading it, however, with a perfect contempt for it, one

discovers in

it after all, a place for the genuine.

Hands that can grasp, eyes

that can dilate, hair that can rise

if it must, these things are important not because a

high-sounding interpretation can be put upon them but because

they are

useful. When they become so derivative as to become

unintelligible,

the same thing may be said for all of us, that we

do not admire what

we cannot understand: the bat

holding on upside down or in quest of something to

eat, elephants pushing, a wild horse taking a roll, a tireless

wolf under

a tree, the immovable critic twitching his skin like a horse

that feels a flea, the base-

ball fan, the statistician—

nor is it valid

to discriminate against "business documents and

school-books"; all these phenomena are important. One must make

a distinction

however: when dragged into prominence by half poets, the

result is not poetry,

nor till the poets among us can be

"literalists of

the imagination"—above

insolence and triviality and can present

for inspection, "imaginary gardens with real toads in them,"

shall we have

it. In the meantime, if you demand on the one hand,

the raw material of poetry in

all its rawness and

that which is on the other hand

genuine, you are interested in poetry.

Selected works

- Poems, 1921. Published in London by H. D. without Moore's knowledge.

- Observations, 1924.

- Selected Poems, 1935. Introduction by T. S. Eliot.

- The Pangolin and Other Verse, 1936.

- What Are Years, 1941.

- Nevertheless, 1944.

- A Face, 1949.

- Collected Poems, 1951.

- Fables of La Fontaine, 1954. Verse translations of La Fontaine's fables.

- Predilections: Literary Essays, 1955.

- Idiosyncracy and Technique, 1966.

- Like a Bulwark, 1956.

- O To Be a Dragon, 1959.

- Idiosyncracy and Technique, 1959.

- The Marianne Moore Reader, 1961.

- The Absentee: A Comedy in Four Acts, 1962. A dramatization of Maria Edgeworth's novel.

- Puss in Boots, The Sleeping Beauty and Cinderella, 1963. Adaptations from Perrault.

- Dress and Kindred Subjects, 1965.

- Poetry and Criticism, 1965.

- Tell Me, Tell Me: Granite, Steel and Other Topics, 1966.

- The Complete Poems, 1967.

- The Accented Syllable, 1969.

- Homage to Henry James, 1971. Essays by Moore, Edmund Wilson, etc.

- The Complete Poems, 1981.

- The Complete Prose, 1986.

- The Selected Letters of Marianne Moore, edited by Bonnie Costello, Celested Goodridge, Cristann Miller. Knopf, 1997.

External links

All links retrieved November 6, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 06:11:30 | 38 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Marianne_Moore | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF