Consciousness

From Nwe

From Nwe Consciousness at its simplest refers to sentience or awareness of internal or external existence. Despite centuries of analyses, definitions, explanations, and debates by philosophers and scientists, consciousness remains puzzling and controversial, being both the most familiar and the most mysterious aspect of our lives. Perhaps the only widely agreed notion about the topic is the intuition that it exists.

Beyond the problem of how to define consciousness, there are also issues of whether non-human creatures have consciousness, and if so in what form; is consciousness a biological function, is it purely material depending on the functions of the physical brain; can machines, or artificial intelligence, have consciousness; is there an evolutionary progression to consciousness such that human consciousness of a higher order; and is human consciousness a spiritual function, not just cognitive? The answers to these questions are the avenue to greater understanding of what it means to be human.

Etymology

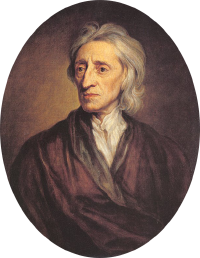

The origin of the modern concept of consciousness is often attributed to John Locke's Essay Concerning Human Understanding, published in 1690, where he discusses the role of consciousness in personal identity:

[C]onsciousness which is inseparable from thinking, and, as it seems to me, essential to it: it being impossible for any one to perceive without perceiving that he does perceive. When we see, hear, smell, taste, feel, meditate, or will anything, we know that we do so. ... For, since consciousness always accompanies thinking, and it is that which makes every one to be what he calls self, and thereby distinguishes himself from all other thinking things, in this alone consists personal identity.[1]

Locke's essay influenced the eighteenth-century view of consciousness, and his definition of consciousness as "the perception of what passes in a man's own mind" appeared in Samuel Johnson's celebrated Dictionary originally published in 1755.[2] "Consciousness" (French: conscience) is also defined in the 1753 volume of Diderot and d'Alembert's Encyclopédie, as "the opinion or internal feeling that we ourselves have from what we do."[3]

The earliest English language uses of "conscious" and "consciousness" date back, however, to the 1500s. The English word "conscious" originally derived from the Latin conscius (con- "together" and scio "to know"). However, the Latin word did not have the same meaning as the English word—it meant "knowing with," in other words "having joint or common knowledge with another."[4] There were, however, many occurrences in Latin writings of the phrase conscius sibi, which translates literally as "knowing with oneself," or in other words "sharing knowledge with oneself about something." This phrase had the figurative meaning of "knowing that one knows," as the modern English word "conscious" does. In its earliest uses in the 1500s, the English word "conscious" retained the meaning of the Latin conscius.

A related word, not to be confused with consciousness, is conscientia, which primarily means moral conscience. In the literal sense, "conscientia" means knowledge-with, that is, shared knowledge. The word first appears in Latin juridical texts by writers such as Cicero.[5] Here, conscientia is the knowledge that a witness has of the deed of someone else. René Descartes (1596–1650) is generally taken to be the first philosopher to use conscientia in a way that does not fit this traditional meaning, using conscientia the way modern speakers would use "conscience." In Search after Truth (1701) he says "conscience or internal testimony" (conscientiâ, vel interno testimonio).[6]

Definitions

At its simplest, consciousness refers to "sentience or awareness of internal or external existence."[7] It has been defined variously in terms of "qualia," subjectivity, the ability to experience or to feel, wakefulness, having a sense of selfhood or soul, the fact that there is something 'that it is like' to 'have' or 'be' it, and the executive control system of the mind.[8] Despite the difficulty in definition, many philosophers believe that there is a broadly shared underlying intuition about what consciousness is.[9] In sum, "Anything that we are aware of at a given moment forms part of our consciousness, making conscious experience at once the most familiar and most mysterious aspect of our lives."[10]

Dictionary definitions

Dictionary definitions of the word "consciousness" extend through several centuries and several associated related meanings. These have ranged from formal definitions to attempts to portray the less easily captured and more debated meanings and usage of the word.

In the Cambridge Dictionary we find consciousness defined as:

- "the state of understanding and realizing something."[11]

The Oxford Dictionary offers these definitions:

- "The state of being aware of and responsive to one's surroundings"

- "A person's awareness or perception of something" and

- "The fact of awareness by the mind of itself and the world."[12]

One formal definition including the range of related meanings is given in Webster's Third New International Dictionary:

-

- "awareness or perception of an inward psychological or spiritual fact: intuitively perceived knowledge of something in one's inner self"

- "inward awareness of an external object, state, or fact"

- "concerned awareness: interest, concern—often used with an attributive noun"

- "the state or activity that is characterized by sensation, emotion, volition, or thought: mind in the broadest possible sense: something in nature that is distinguished from the physical

- "the totality in psychology of sensations, perceptions, ideas, attitudes and feelings of which an individual or a group is aware at any given time or within a particular time span"[13]

In philosophy

Most people have a strong intuition for the existence of what they refer to as consciousness. However, philosophers differ from non-philosophers in their intuitions about what consciousness is.[14]

While non-philosophers would find familiar the elements in the dictionary definitions above, philosophers approach the term somewhat differently. For example, the Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy in 1998 contained the following more complex definition of consciousness:

Philosophers have used the term 'consciousness' for four main topics: knowledge in general, intentionality, introspection (and the knowledge it specifically generates) and phenomenal experience... Something within one's mind is 'introspectively conscious' just in case one introspects it (or is poised to do so). Introspection is often thought to deliver one's primary knowledge of one's mental life. An experience or other mental entity is 'phenomenally conscious' just in case there is 'something it is like' for one to have it. The clearest examples are: perceptual experience, such as tastings and seeings; bodily-sensational experiences, such as those of pains, tickles and itches; imaginative experiences, such as those of one's own actions or perceptions; and streams of thought, as in the experience of thinking 'in words' or 'in images.' Introspection and phenomenality seem independent, or dissociable, although this is controversial.[15]

In a more skeptical definition, Stuart Sutherland exemplified some of the difficulties in fully ascertaining all of its cognate meanings in his entry for the 1989 version of the Macmillan Dictionary of Psychology:

Consciousness—The having of perceptions, thoughts, and feelings; awareness. The term is impossible to define except in terms that are unintelligible without a grasp of what consciousness means. Many fall into the trap of equating consciousness with self-consciousness—to be conscious it is only necessary to be aware of the external world. Consciousness is a fascinating but elusive phenomenon: it is impossible to specify what it is, what it does, or why it has evolved. Nothing worth reading has been written on it.[16]

Generally, philosophers and scientists have been unhappy about the difficulty of producing a definition that does not involve circularity or fuzziness.[16]

Philosophical issues

Western philosophers since the time of Descartes and Locke have struggled to comprehend the nature of consciousness and how it fits into a larger picture of the world. These issues remain central to both continental and analytic philosophy, in phenomenology and the philosophy of mind, respectively. Some basic questions include: whether consciousness is the same kind of thing as matter; whether it may ever be possible for computing machines like computers or robots to be conscious; how consciousness relates to language; how consciousness as Being relates to the world of experience; the role of the self in experience; and whether the concept is fundamentally coherent.

Mind–body problem

Mental processes (such as consciousness) and physical processes (such as brain events) seem to be correlated. However, the specific nature of the connection is unknown. The philosophy of mind has given rise to many stances regarding consciousness. In particular, the two major schools of thought regarding the nature of the mind and the body, Dualism and monism, are directly related to the nature of consciousness.

Dualism, originally proposed by René Descartes, is the position that mind and body are separate from each other.[17] Dualist theories maintain Descartes' rigid distinction between the realm of thought, where consciousness resides, and the realm of matter, but give different answers for how the two realms relate to each other. The two main types of dualism are substance dualism, which holds that the mind is formed of a distinct type of substance not governed by the laws of physics, and property dualism, which holds that the laws of physics are universally valid but cannot be used to explain the mind.

Monism, on the other hand, rejects the dualist separation and maintains that mind and body are, at the most fundamental level, the same realm of being of which consciousness and matter are both aspects. This can mean that both are mental, such that only thought or experience truly exists and matter is merely an illusion (idealism); or that everything is material (physicalism), which holds that the mind consists of matter organized in a particular way; and neutral monism, which holds that both mind and matter are aspects of a distinct essence that is itself identical to neither of them.

These two schools of dualism and monism have different conceptions of consciousness, with arguments for and against on both sides. This has led a number of philosophers to reject the dualism/monism dichotomy. Gilbert Ryle, for example, argued that the traditional understanding of consciousness depends on a Cartesian dualist outlook that improperly distinguishes between mind and body, or between mind and world. Thus, by speaking of "consciousness" we end up misleading ourselves by thinking that there is any sort of thing as consciousness separated from behavioral and linguistic understandings.[18]

David Chalmers formulated what he calls the "hard problem of consciousness," which distinguishes between "easy" (cognitive) problems of consciousness, such as explaining object discrimination or verbal reports, and the single hard problem, which could be stated "why does the feeling which accompanies awareness of sensory information exist at all?" The easy problems are at least theoretically answerable via the dominant monistic philosophy of mind: physicalism. The hard problem, on the other hand, is not. He argues for an "explanatory gap" from the objective to the subjective mental experience, a view which he characterizes as "naturalistic dualism": naturalistic because he believes mental states are caused by physical systems (brains); dualist because he believes mental states are ontologically distinct from and not reducible to physical systems.[19]

Problem of other minds

Many philosophers consider experience to be the essence of consciousness, and believe that experience can fully be known only from the inside, subjectively. But if consciousness is subjective and not visible from the outside, why do the vast majority of people believe that other people are conscious, but rocks and trees are not? This is what is known as the problem of other minds.[20]

The most commonly given answer is that we attribute consciousness to other people because we see that they resemble us in appearance and behavior. We reason that if they look like us and act like us, they must be like us in other ways, including having experiences of the sort that we do.[20] More broadly, philosophers who do not accept the possibility of philosophical zombies, entities that lack consciousness but otherwise appear and behave as humans,[21] generally believe that consciousness is reflected in behavior (including verbal behavior), and that we attribute consciousness on the basis of behavior. In other words, we attribute experiences to people because of what they can do, including the fact that they can tell us about their experiences.

Animal consciousness

The topic of animal consciousness is beset by a number of difficulties. It poses the problem of other minds in an especially severe form, because non-human animals, lacking the ability to express human language, cannot tell us about their experiences. Also, it is difficult to reason objectively about the question, because a denial that an animal is conscious is often taken to imply that it does not feel, its life has no value, and that harming it is not morally wrong. Most people have a strong intuition that some animals, such as cats and dogs, are conscious, while others, such as insects, are not; but the sources of this intuition are not obvious.

Philosophers who consider subjective experience the essence of consciousness also generally believe, as a correlate, that the existence and nature of animal consciousness can never rigorously be known. Thomas Nagel spelled out this point of view in an influential essay titled What Is it Like to Be a Bat?. He stated that an organism is conscious "if and only if there is something that it is like to be that organism—something it is like for the organism"; and he argued that no matter how much we know about an animal's brain and behavior, we can never really put ourselves into the mind of the animal and experience its world in the way it does itself.[22]

On July 7, 2012, eminent scientists from different branches of neuroscience gathered at the University of Cambridge to celebrate the Francis Crick Memorial Conference, which deals with consciousness in humans and pre-linguistic consciousness in nonhuman animals. After the conference, they signed in the presence of Stephen Hawking the Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness which concluded that consciousness exists in animals:

The absence of a neocortex does not appear to preclude an organism from experiencing affective states. Convergent evidence indicates that non-human animals have the neuroanatomical, neurochemical, and neurophysiological substrates of conscious states along with the capacity to exhibit intentional behaviors. Consequently, the weight of evidence indicates that humans are not unique in possessing the neurological substrates that generate consciousness. Non-human animals, including all mammals and birds, and many other creatures, including octopuses, also possess these neurological substrates.[23]

Artifact consciousness

The idea of an artifact made conscious is an ancient theme of mythology, appearing for example in the Greek myth of Pygmalion, who carved a statue that was magically brought to life, and in medieval Jewish stories of the Golem, a magically animated homunculus built of clay.[24] However, the possibility of actually constructing a conscious machine was probably first discussed by Ada Lovelace, in a set of notes written in 1842 about the Analytical Engine invented by Charles Babbage, a precursor (never built) to modern electronic computers. Lovelace was essentially dismissive of the idea that a machine such as the Analytical Engine could think in a human-like way:

It is desirable to guard against the possibility of exaggerated ideas that might arise as to the powers of the Analytical Engine. ... The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform. It can follow analysis; but it has no power of anticipating any analytical relations or truths. Its province is to assist us in making available what we are already acquainted with.[25]

One of the most influential contributions to this question was an essay written in 1950 by pioneering computer scientist Alan Turing in which he stated that the question "Can machines think?" is meaningless. Instead he proposed "the imitation game," which has become known as the Turing test.[26] To pass the test, a computer must be able to imitate a human well enough to fool interrogators.[27]

The Turing test is commonly cited in discussions of artificial intelligence as a proposed criterion for machine consciousness, provoking a great deal of philosophical debate. For example, Daniel Dennett and Douglas Hofstadter argue that anything capable of passing the Turing test is necessarily conscious.[28] On the other hand, David Chalmers argues that a philosophical zombie, an imaginary entity that is physically indistinguishable from a human being and behaves like a human being in every way but nevertheless lacks consciousness, could pass the test. By definition, such an entity is not conscious.[19]

In a lively exchange over what has come to be referred to as "the Chinese room argument," John Searle sought to refute the claim of proponents of "strong artificial intelligence (AI)" that a computer program can be conscious, though agreed with advocates of "weak AI" that computer programs can be formatted to "simulate" conscious states. He argued that consciousness has subjective, first-person causal powers by being essentially intentional due to the way human brains function biologically. Conscious persons can perform computations, but consciousness is not inherently computational the way computer programs are.

To illustrate the difference, Searle described a thought experiment involving a room with one monolingual English speaker, a book that designates a combination of Chinese symbols to be output paired with Chinese symbol input, and boxes filled with Chinese symbols. In this case, the English speaker is acting as a computer and the rule book as a program. Searle argues that with such a machine, he would be able to process the inputs to outputs perfectly without having any understanding of Chinese, nor having any idea what the questions and answers could possibly mean. On the other hand, if the experiment were done in English, the person would be able to take questions and give answers without any algorithms for English questions, and he would be effectively aware of what was being said and the purposes it might serve. The person would pass the Turing test of answering the questions in both languages, but would be conscious of what he is doing only when the language is English. Put another way, computer programs can pass the Turing test for processing the syntax of a language, but syntax cannot lead to semantic meaning in the way strong AI advocates hope.[29]

Searle did not clarify what was needed to make the leap from using syntactic rules to understanding of meaning, and at the time of his initial writing computers were limited to computational information processing. Since then, intelligent virtual assistants, such as Apple' Siri, have become commonplace. While they are capable of answering a number of questions, they have not yet reached the human standard of conversation. IBM claims that Watson “knows what it knows, and knows what it does not know,” and indeed was able to beat human champions on the television game show Jeopardy, a feat that relies heavily on language abilities and inference. However, as John Searle pointed out, this is not the same as being aware of what it meant to win the game show, understanding that it was a game, and that it won.[30]

The best computers have been shown only to simulate human cognition; they have not been shown to demonstrate consciousness; nor have they put an end to the question of whether there is a biological basis to consciousness.[31]

Phenomenology

Phenomenology is a method of inquiry that attempts to examine the structure of consciousness in its own right, putting aside problems regarding the relationship of consciousness to the physical world. This approach was first proposed by the philosopher Edmund Husserl, and later elaborated by other philosophers and scientists.[32]

Phenomenology is, in Husserl's formulation, the study of experience and the ways in which things present themselves in and through experience. Taking its starting point from the first-person perspective, phenomenology attempts to describe the essential features or structures of a given experience or any experience in general. One of the central structures of any experience is its intentionality, or its being directed toward some object or state of affairs. The theory of intentionality, the central theme of phenomenology, maintains that all experience necessarily has this object-relatedness and thus one of the catch phrases of phenomenology is “all consciousness is consciousness of.”

Husserl's original concept gave rise to two distinct lines of inquiry, in philosophy and in psychology. In philosophy, phenomenology has largely been devoted to fundamental metaphysical questions, such as the nature of intentionality ("aboutness"). In psychology, phenomenology has meant attempting to investigate consciousness using the method of introspection, which means looking into one's own mind and reporting what one observes. This method fell into disrepute in the early twentieth century because of grave doubts about its reliability, but has been rehabilitated to some degree, especially when used in combination with techniques for examining brain activity.[33]

Introspectively, the world of conscious experience seems to have considerable structure. Immanuel Kant asserted that the world as we perceive it is organized according to a set of fundamental "intuitions," which include 'object' (we perceive the world as a set of distinct things); 'shape'; 'quality' (color, warmth, etc.); 'space' (distance, direction, and location); and 'time'. Some of these constructs, such as space and time, correspond to the way the world is structured by the laws of physics; for others the correspondence is not as clear. Understanding the physical basis of qualities, such as redness or pain, has been particularly challenging. Some philosophers have argued that it is intrinsically unsolvable, because qualities ("qualia") are ineffable; that is, they are "raw feels," incapable of being analyzed into component processes.[34]

Scientific study

Since the dawn of Newtonian science with its vision of simple mechanical principles governing the entire universe, it has been tempting to explain consciousness in purely physical terms. The first influential writer to propose such an idea explicitly was Julien Offray de La Mettrie, in his book Man a Machine (L'homme machine), which dealt with the notion only in the abstract.[35]

Broadly viewed, such scientific approaches are based on two core concepts. The first identifies the content of consciousness with the experiences that are reported by human subjects; the second makes use of the concept of consciousness that has been developed by neurologists and other medical professionals who deal with patients whose behavior is impaired. In both cases, the ultimate goals are to develop techniques for assessing consciousness objectively in humans as well as other animals, and to understand the neural and psychological mechanisms that underlie it.[36]

Consciousness has also become a significant topic of interdisciplinary research in cognitive science, involving fields such as psychology, linguistics, anthropology, neuropsychology, and neuroscience. The primary focus is on understanding what it means biologically and psychologically for information to be present in consciousness—that is, on determining the neural and psychological correlates of consciousness. The majority of experimental studies assess consciousness in humans by asking subjects for a verbal report of their experiences (such as, "tell me if you notice anything when I do this"). Issues of interest include phenomena such as subliminal perception, blindsight, denial of impairment, and altered states of consciousness produced by alcohol and other drugs or meditative techniques.

Measurement

Experimental research on consciousness presents special difficulties due to the lack of a universally accepted operational definition. In the majority of experiments that are specifically about consciousness, the subjects are human, and the criterion used is verbal report. In other words, subjects are asked to describe their experiences, and their descriptions are treated as observations of the contents of consciousness.[37] For example, subjects who stare continuously at a Necker cube usually report that they experience it "flipping" between two 3D configurations, even though the stimulus itself remains the same.

Verbal report is widely considered to be the most reliable indicator of consciousness, but it raises a number of issues.[38] If verbal reports are treated as observations, akin to observations in other branches of science, then the possibility arises that they may contain errors—but it is difficult to make sense of the idea that subjects could be wrong about their own experiences, and even more difficult to see how such an error could be detected.[39] Another issue with verbal report as a criterion is that it restricts the field of study to humans who have language. This approach cannot be used to study consciousness in other species, pre-linguistic children, or people with types of brain damage that impair language. A third issue is that those who dispute the validity of the Turing test may feel that it is possible, at least in principle, for verbal report to be dissociated from consciousness entirely: a philosophical zombie may give detailed verbal reports of awareness in the absence of any genuine awareness.[19]

Although verbal report is in practice the "gold standard" for ascribing consciousness, it is not the only possible criterion.[38] In medicine, consciousness is assessed as a combination of verbal behavior, arousal, brain activity, and purposeful movement. The last three of these can be used as indicators of consciousness when verbal behavior is absent. Their reliability as indicators of consciousness is disputed, however, due to numerous studies showing that alert human subjects can be induced to behave purposefully in a variety of ways in spite of reporting a complete lack of awareness.[40]

Another approach applies specifically to the study of self-awareness, that is, the ability to distinguish oneself from others. In the 1970s Gordon Gallup developed an operational test for self-awareness, known as the mirror test. The test examines whether animals are able to differentiate between seeing themselves in a mirror versus seeing other animals. The classic example involves placing a spot of coloring on the skin or fur near the individual's forehead and seeing if they attempt to remove it or at least touch the spot, thus indicating that they recognize that the individual they are seeing in the mirror is themselves.[41] Humans (older than 18 months) and other great apes, bottlenose dolphins, killer whales, pigeons, European magpies and elephants have all been observed to pass this test.

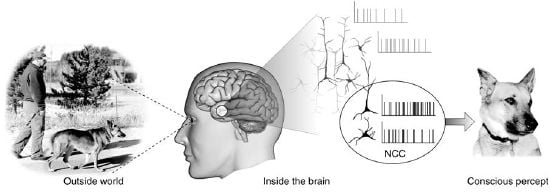

Neural correlates

In neuroscience, a great deal of effort has gone into investigating how the perceived world of conscious awareness is constructed inside the brain. This is done by examining the relationship between the experiences reported by subjects and the activity that simultaneously takes place in their brains—that is, studies of the neural correlates of consciousness. The hope is to find activity in a particular part of the brain, or a particular pattern of global brain activity, which will be strongly predictive of conscious awareness. Such studies use brain imaging techniques, such as EEG and fMRI, for physical measures of brain activity.[36]

The process of constructing conscious awareness is generally thought to involve two primary mechanisms: (1) hierarchical processing of sensory inputs, and (2) memory. Signals arising from sensory organs are transmitted to the brain and then processed in a series of stages, which extract multiple types of information from the raw input. In the visual system, for example, sensory signals from the eyes are transmitted to the thalamus and then to the primary visual cortex. Studies have shown that activity in primary sensory areas of the brain is not sufficient to produce consciousness. It is possible for subjects to report a lack of awareness even when areas such as the primary visual cortex show clear electrical responses to a stimulus.[36] Higher brain areas, especially the prefrontal cortex, which is involved in a range of higher cognitive functions collectively known as executive functions, then extract features such as three-dimensional structure, shape, color, and motion.[42] Memory comes into play in at least two ways during this activity. First, it allows sensory information to be evaluated in the context of previous experience. Second, and even more importantly, working memory allows information to be integrated over time so that it can generate a stable representation of the world.

Biological function and evolution

Opinions are divided as to where in biological evolution consciousness emerged and about whether or not consciousness has any survival value. Even among writers who consider consciousness to be well-defined, there is widespread dispute about which animals other than humans can be said to possess it.[43]

It has been argued that consciousness emerged (i) exclusively with the first humans, (ii) exclusively with the first mammals, (iii) independently in mammals and birds, or (iv) with the first reptiles.[44] Other suggestions include the appearance of consciousness in the first animals with nervous systems or early vertebrates in the Cambrian over 500 million years ago, or a gradual evolution of consciousness.[45] Another viewpoint distinguishes between primary consciousness, which is a trait shared by humans and non-human animals, and higher-order consciousness which appears only in humans along with their capacity for language.[46] Supporting this distinction, several scholars including Pinker, Chomsky, and Luria have indicated the importance of the emergence of human language as a regulative mechanism of learning and memory in the context of the development of higher-order consciousness. Each of these evolutionary scenarios raises the question of the possible survival value of consciousness.

Some writers have argued that consciousness can be viewed from the standpoint of evolutionary biology as an adaptation that increases fitness. For example, consciousness allows an individual to make distinctions between appearance and reality.[47] This ability would enable a creature to recognize the likelihood that their perceptions are deceiving them (that water in the distance may be a mirage, for instance) and behave accordingly. It could also facilitate the manipulation of others by recognizing how things appear to them for both cooperative and devious ends.

William James argued that if the preservation and development of consciousness occurs in biological evolution, it is plausible that consciousness has not only been influenced by neural processes, but has had a survival value itself; and it could only have had this if it had been efficacious: "Consciousness ... has been slowly evolved in the animal series, and resembles in this all organs that have a use."[48] A similar evolutionary argument was presented by Karl Popper.[49]

Medical aspects

The medical approach to consciousness is practically oriented. It derives from a need to treat people whose brain function has been impaired as a result of disease, brain damage, toxins, or drugs. Whereas the philosophical approach to consciousness focuses on its fundamental nature and its contents, the medical approach focuses on the level of consciousness, ranging from coma and brain death at the low end, to full alertness and purposeful responsiveness at the high end.[50]

Assessment

In medicine, consciousness is assessed by observing a patient's arousal and responsiveness, and can be seen as a continuum of states ranging from full alertness and comprehension, through disorientation, delirium, loss of meaningful communication, and finally loss of movement in response to painful stimuli.[34] The degree of consciousness is measured by standardized behavior observation scales such as the Glasgow Coma Scale, which is composed of three tests: eye, verbal, and motor responses. Scores range from 3 to 15, with a score of 3 to 8 indicating coma, and 15 indicating full consciousness.

Issues of practical concern include how the presence of consciousness can be assessed in severely ill, comatose, or anesthetized people, and how to treat conditions in which consciousness is impaired or disrupted.

Disorders of consciousness

Medical conditions that inhibit consciousness are considered disorders of consciousness. This category generally includes minimally conscious state and persistent vegetative state, but sometimes also includes the less severe locked-in syndrome and more severe chronic coma. Finally, brain death results in an irreversible disruption of consciousness.

While other conditions may cause a moderate deterioration (for example, dementia and delirium) or transient interruption (such as grand mal and petit mal seizures) of consciousness, they are not included in this category.

| Disorder | Description |

|---|---|

| Locked-in syndrome | The patient has awareness, sleep-wake cycles, and meaningful behavior (viz., eye-movement), but is isolated due to quadriplegia and pseudobulbar palsy. |

| Minimally conscious state | The patient has intermittent periods of awareness and wakefulness and displays some meaningful behavior. |

| Persistent vegetative state | The patient has sleep-wake cycles, but lacks awareness and only displays reflexive and non-purposeful behavior. |

| Chronic coma | The patient lacks awareness and sleep-wake cycles and only displays reflexive behavior. |

| Brain death | The patient lacks awareness, sleep-wake cycles, and brain-mediated reflexive behavior. |

Altered states of consciousness

There are some brain states in which consciousness seems to be absent, including dreamless sleep, coma, and death. There are also a variety of circumstances that can change the relationship between the mind and the world in less drastic ways, producing what are known as altered states of consciousness. Some altered states occur naturally; others can be produced by drugs or brain damage. Altered states can be accompanied by changes in thinking, disturbances in the sense of time, feelings of loss of control, changes in emotional expression, alternations in body image, and changes in meaning or significance.

The two most widely accepted altered states are sleep and dreaming. Although dream sleep and non-dream sleep appear very similar to an outside observer, each is associated with a distinct pattern of brain activity, metabolic activity, and eye movement; each is also associated with a distinct pattern of experience and cognition. During ordinary non-dream sleep, people who are awakened report only vague and sketchy thoughts, and their experiences do not cohere into a continuous narrative. During dream sleep, in contrast, people who are awakened report rich and detailed experiences in which events form a continuous progression, which may be interrupted by bizarre or fantastic intrusions. Thought processes during the dream state frequently show a high level of irrationality. Both dream and non-dream states are associated with severe disruption of memory, usually disappearing in seconds in the non-dream state, and in minutes after awakening from a dream unless actively refreshed.[51]

Studies of altered states of consciousness by Charles Tart in the 1960s and 1970s led to the possible identification of a number of component processes of consciousness which can be altered by drugs or other manipulations. These include exteroception (sensing the external world); interoception (sensing the body); input-processing (seeing meaning); emotions; memory; time sense; sense of identity; evaluation and cognitive processing; motor output; and interaction with the environment.[52]

A variety of psychoactive drugs, including alcohol, have notable effects on consciousness. These range from a simple dulling of awareness produced by sedatives, to increases in the intensity of sensory qualities produced by stimulants, cannabis, empathogens–entactogens such as MDMA ("Ecstasy"), or most notably by the class of drugs known as psychedelics. LSD, mescaline, psilocybin, Dimethyltryptamine, and others in this group can produce major distortions of perception, including hallucinations; some users even describe their drug-induced experiences as mystical or spiritual in quality.

Research into physiological changes in yogis and people who practice various techniques of meditation suggests brain waves during meditation differ from those corresponding to ordinary relaxation. It has been disputed, however, whether these are physiologically distinct states of consciousness.[53]

Stream of consciousness

William James is usually credited with popularizing the idea that human consciousness flows like a stream. According to James, the "stream of thought" is governed by five characteristics:

- Every thought tends to be part of a personal consciousness.

- Within each personal consciousness thought is always changing.

- Within each personal consciousness thought is sensibly continuous.

- It always appears to deal with objects independent of itself.

- It is interested in some parts of these objects to the exclusion of others.[54]

A similar concept appears in Buddhist philosophy, expressed by the Sanskrit term Citta-saṃtāna, which is usually translated as mindstream or "mental continuum." Buddhist teachings describe consciousness as manifesting moment to moment as sense impressions and mental phenomena that are continuously changing. The moment-by-moment manifestation of the mind-stream is said to happen in every person all the time. The purpose of the Buddhist practice of mindfulness is to understand the inherent nature of the consciousness and its characteristics.[55]

In the west, the primary impact of the idea has been on literature rather than science. Stream of consciousness as a narrative mode means writing in a way that attempts to portray the moment-to-moment thoughts and experiences of a character. This technique reached its fullest development in the novels of James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, although it has also been used by many other noted writers.[56]

Spiritual approaches

To most philosophers, the word "consciousness" connotes the relationship between the mind and the world. To writers on spiritual or religious topics, it frequently connotes the relationship between the mind and God, or the relationship between the mind and deeper truths that are thought to be more fundamental than the physical world. The spiritual approach distinguishes various levels of consciousness, forming a spectrum with ordinary awareness at one end, and more profound types of awareness at higher levels.[57]

Notes

- ↑ John Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (Wordsworth Editions Ltd, 2014, ISBN 978-1840227321).

- ↑ Samuel Johnson, A Dictionary of the English Language (Forgotten Books, 2016, ISBN 978-1333070120).

- ↑ Consciousness The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ↑ C.S. Lewis, Studies in words (Cambridge University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-1107688650).

- ↑ Barbara Cassin, Emily Apter, Jacques Lezra, and Michael Wood (eds.), Dictionary of Untranslatables: A Philosophical Lexicon (Princeton University Press, 2014, ISBN 978-0691138701).

- ↑ Sara Heinämaa, Vili Lähteenmäki, and Pauliina Remes (eds.), Consciousness: From Perception to Reflection in the History of Philosophy (Springer, 2007, ISBN 978-1402060816).

- ↑ consciousness Merriam-Webster. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ↑ G. William Farthing, The Psychology of Consciousness (Pearson College Div., 1991, ISBN 978-0137286683).

- ↑ Ted Honderich, (ed.), The Oxford Companion to Philosophy (Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0199264797).

- ↑ Susan Schneider and Max Velmans (eds.), The Blackwell Companion to Consciousness (Wiley-Blackwell, 2017, ISBN 978-0470674079).

- ↑ consciousness Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ↑ consciousness Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ↑ Philip Babcock Gove (ed.), Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language (Merriam-Webster, 1993, ISBN 978-0877792017).

- ↑ Justin Sytsma and Edouard Machery, Two conceptions of subjective experience Philosophical Studies 151(2) (2010): 299–327. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ↑ Edward Craig (ed.), Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Routledge, 1998, ISBN 978-0415073103).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Stuart Sutherland, Macmillan Dictionary of Psychology (Palgrave Macmillan, 1989, ISBN 978-0333388297).

- ↑ René Descartes, John Cottingham (trans.), Meditations on First Philosophy (Cambridge University Press, 2017, ISBN 978-1107665736).

- ↑ Gilbert Ryle, The Concept of Mind (University of Chicago Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0226732961).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 David J. Chalmers, The Conscious Mind (Oxford University Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0195117899).

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Alec Hyslop, Other Minds (Springer, 2010, ISBN 978-9048144976).

- ↑ Robert Kirk, Zombies Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2019 Edition). Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ↑ Thomas Nagel, Mortal Questions (Cambridge University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-1107604711).

- ↑ The Cambridge Declaration on Consciousness July 7, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ↑ Moshe Idel, Golem: Jewish Magical and Mystical Traditions on the Artificial Anthropoid (KTAV Publishing House, 2019, ISBN 978-1602803527).

- ↑ Ada Lovelace, Sketch of The Analytical Engine, Note G Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ↑ Alan M. Turing, Computing Machinery and Intelligence Mind 59 (October 1950): 433-460. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ↑ Stuart Shieber, The Turing Test: Verbal Behavior as the Hallmark of Intelligence (MIT Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0262692939).

- ↑ Daniel Dennett and Douglas Hofstadter,The Mind's I: Fantasies And Reflections On Self & Soul (Basic Books, 2001, ISBN 978-0465030910).

- ↑ John R. Searle, Minds, brains, and programs Behavioral and Brain Sciences 3(3) (1980): 417-457.

- ↑ John Searle, Watson Doesn't Know It Won on 'Jeopardy!' The Wall Street Journal, February 23, 2011. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ↑ The Chinese Room Argument Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ↑ Robert Sokolowski, Introduction to Phenomenology (Cambridge University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0521667920).

- ↑ Anthony Jack and Andreas Roepstorff (eds.), Trusting the Subject? Volume 1 (Imprint Academic, 2003, ISBN 978-0907845560).

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Ned Block, Owen J. Flanagan, and Guven Guzeldere (eds.), The Nature of Consciousness: Philosophical Debates (A Bradford Book, 1997, ISBN 978-0262522106).

- ↑ Julien Offray de La Mettrie, Machine Man and Other Writings (Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0521472586).

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Christof Koch, The Quest for Consciousness: A Neurobiological Approach (Roberts & Co, 2004, ISBN 978-0974707709).

- ↑ Bernard J. Baars, A Cognitive Theory of Consciousness (Cambridge University Press, 1993, ISBN 978-0521427432).

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Steven Laureys (ed.), The Boundaries of Consciousness: Neurobiology and Neuropathology (Elsevier Science, 2005, ISBN 978-0444518514).

- ↑ A.J. Marcel and E. Bisiach (eds.), Consciousness in Contemporary Science (Clarendon Press, 1992, ISBN 978-0198522379).

- ↑ Thomas Schmidt and Dirk Vorberg, Criteria for unconscious cognition: Three types of dissociation Perception & Psychophysics 68(3) (April 2006): 489–504. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ↑ Gordon Gallup, Chimpanzees: Self recognition Science 167( 3914) (1970): 86–87. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ↑ M.R. Bennett and P.M.S. Hacker, Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience (Wiley-Blackwell, 2003, ISBN 978-1405108386).

- ↑ Stephen Budiansky, If a Lion Could Talk: Animal Intelligence and the Evolution of Consciousness (Free Press, 2015, ISBN 978-1501142741).

- ↑ Hans Liljenström and Peter Århem (eds.), Consciousness Transitions: Phylogenetic, Ontogenetic and Physiological Aspects (Elsevier Science, 2007, ISBN 978-0444529770).

- ↑ Donald R. Griffin, Animal Minds (University Of Chicago Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0226308647).

- ↑ Gerald Edelman and Giulio Tononi, A Universe Of Consciousness: How Matter Becomes Imagination (Basic Books, 2001, ISBN 978-0465013777).

- ↑ Peter Carruthers, Phenomenal Consciousness: A Naturalistic Theory (Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0521781732).

- ↑ William James, Are We Automata? Mind 4(13) (1879): 1–22. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ↑ Karl Popper and John C. Eccles, The Self and Its Brain: An Argument for Interactionism (Routledge, 1984, ISBN 978-0415058988).

- ↑ Steven Laureys and Giulio Tononi (eds.), The Neurology of Consciousness: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuropathology (Academic Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0123741684).

- ↑ Edward F. Pace-Schott, Mark Solms, Mark Blagrove, and Stevan Harnad (eds.), Sleep and Dreaming: Scientific Advances and Reconsiderations (Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0521008693).

- ↑ Charles Tart, States of Consciousness (iUniverse, 2001, ISBN 978-0595151967).

- ↑ Michael Murphy, Steven Donovan, et al. The Physical and Psychological Effects of Meditation (Institute of Noetic Sciences, 1997, ISBN 978-0943951362).

- ↑ William James, The Principles of Psychology, Vol. 1 (Dover Publications, 1950, ISBN 978-0486203812).

- ↑ Doris Wolter (ed.), Losing the Clouds, Gaining the Sky: Buddhism and the Natural Mind (Wisdom Publications, 2007, ISBN 978-0861713592).

- ↑ Robert Humphrey, Stream of Consciousness In the Modern Novel (University of California Press, 1972, ISBN 978-0520005853).

- ↑ Ken Wilber, The Spectrum of Consciousness (Quest Books, 1993, ISBN 978-0835606950).

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baars, Bernard J. A Cognitive Theory of Consciousness. Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0521427432

- Bennett, M.R., and P.M.S. Hacker. Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience. Wiley-Blackwell, 2003. ISBN 978-1405108386

- Block, Ned, Owen J. Flanagan, and Guven Guzeldere (eds.). The Nature of Consciousness: Philosophical Debates. A Bradford Book, 1997. ISBN 978-0262522106

- Budiansky, Stephen. If a Lion Could Talk: Animal Intelligence and the Evolution of Consciousness. Free Press, 2015. ISBN 978-1501142741

- Carruthers, Peter. Phenomenal Consciousness: A Naturalistic Theory. Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0521781732

- Cassin, Barbara, Emily Apter, Jacques Lezra, and Michael Wood (eds.). Dictionary of Untranslatables: A Philosophical Lexicon. Princeton University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0691138701

- Chalmers, David J. The Conscious Mind. Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0195117899

- Chalmers, David J. The Character of Consciousness. Oxford University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0195311112

- Craig, Edward (ed.). Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Routledge, 1998. ISBN 978-0415073103

- Descartes, René, John Cottingham (trans.). Meditations on First Philosophy. Cambridge University Press, 2017. ISBN 978-1107665736

- Edelman, Gerald, and Giulio Tononi. A Universe Of Consciousness: How Matter Becomes Imagination. Basic Books, 2001. ISBN 978-0465013777

- Gove, Philip Babcock (ed.). Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language. Merriam-Webster, 1993. ISBN 978-0877792017

- Griffin, Donald R. Animal Minds. University Of Chicago Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0226308647

- Heinämaa, Sara, Vili Lähteenmäki, and Pauliina Remes (eds.). Consciousness: From Perception to Reflection in the History of Philosophy. Springer, 2007. ISBN 978-1402060816

- Honderich, Ted (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0199264797

- Humphrey, Robert. Stream of Consciousness In the Modern Novel. University of California Press, 1972. ISBN 978-0520005853

- Hyslop, Alec. Other Minds. Springer, 2010. ISBN 978-9048144976

- Idel, Moshe. Golem: Jewish Magical and Mystical Traditions on the Artificial Anthropoid. KTAV Publishing House, 2019. ISBN 978-1602803527

- Jack, Anthony, and Andreas Roepstorff (eds.). Trusting the Subject? Volume 1. Imprint Academic, 2003. ISBN 978-0907845560

- James, William. The Principles of Psychology, Vol. 1. Dover Publications, 1950. ISBN 978-0486203812

- Johnson, Samuel. A Dictionary of the English Language. Forgotten Books, 2016. ISBN 978-1333070120

- Koch, Christof. The Quest for Consciousness: A Neurobiological Approach. Roberts & Co, 2004. ISBN 978-0974707709

- La Mettrie, Julien Offray de. Machine Man and Other Writings. Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0521472586

- Laureys, Steven (ed.). The Boundaries of Consciousness: Neurobiology and Neuropathology. Elsevier Science, 2005 ISBN 978-0444518514

- Laureys, Steven, and Giulio Tononi (eds.). The Neurology of Consciousness: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuropathology. Academic Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0123741684

- Lewis, C.S. Studies in Words. Cambridge University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-1107688650

- Liljenström, Hans, and Peter Århem (eds.). Consciousness Transitions: Phylogenetic, Ontogenetic and Physiological Aspects. Elsevier Science, 2007. ISBN 978-0444529770

- Locke, John. An Essay Concerning Human Understanding. Wordsworth Editions Ltd, 2014. ISBN 978-1840227321

- Marcel, A.J., and E. Bisiach (eds.). Consciousness in Contemporary Science. Clarendon Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0198522379

- Murphy, Michael, Steven Donovan, et al. The Physical and Psychological Effects of Meditation. Institute of Noetic Sciences, 1997. ISBN 978-0943951362

- Nagel, Thomas. Mortal Questions. Cambridge University Press, 2012. ISBN 1107604710

- Pace-Schott, Edward F., Mark Solms, Mark Blagrove, and Stevan Harnad (eds.). Sleep and Dreaming: Scientific Advances and Reconsiderations. Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0521008693

- Popper, Karl, and John C. Eccles. The Self and Its Brain: An Argument for Interactionism. Routledge, 1984. ISBN 978-0415058988

- Ryle, Gilbert. The Concept of Mind. University of Chicago Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0226732961

- Schneider, Susan, and Max Velmans (eds.). The Blackwell Companion to Consciousness. Wiley-Blackwell, 2017. ISBN 978-0470674079

- Shieber, Stuart. The Turing Test: Verbal Behavior as the Hallmark of Intelligence. MIT Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0262692939

- Sutherland, Stuart. Macmillan Dictionary of Psychology. Palgrave Macmillan, 1989. ISBN 978-0333388297

- Tart, Charles. States of Consciousness. iUniverse, 2001. ISBN 978-0595151967

- Wolter, Doris (ed.). Losing the Clouds, Gaining the Sky: Buddhism and the Natural Mind. Wisdom Publications, 2007. ISBN 978-0861713592

- Wilber, Ken. The Spectrum of Consciousness. Quest Books, 1993. ISBN 978-0835606950

External links

All links retrieved July 14, 2020.

- Consciousness Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Consciousness Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- What Is Consciousness?

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 02:04:25 | 369 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Conscious | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF