Exodus, Book Of

From Nwe

From Nwe | Books of the |

Exodus (meaning: "mass migration or exiting of a people from an area") is the second book of the Old Testament or Hebrew Bible. The major events of the book concern the calling of the prophet Moses as well as the departure of the Israelites from Egypt.

The Book of Exodus presents some of the Bible's most dramatic moments, from the rescue of the infant Moses from the Nile, to the scene of Moses meeting God in the burning bush, Moses and Aaron confronting Pharaoh, the miracles of the plagues visited by God upon Egypt, the Passover, the escape from Egypt, the parting of the sea, the episode of the golden calf, and finally the successful construction of the tabernacle with its Ark of the Covenant. Scholars debate the historicity of Exodus, seeing multiple sources and several authors with varying theological outlooks.

Summary

Introduction

While Exodus is the name assigned to the book in Christian tradition, Jews also refer to it by its first words Ve-eleh shemot (ואלה שמות) (i.e., "And these are the names") or simply "Shemot" (Names). The Greek Septuagint version of the Hebrew Bible designated this second book of the Pentateuch as "Exodus" (Ἔξοδος), meaning "departure" or "out-going." The Latin translation adopted this name, which passed into other languages.

The story of the Exodus is both inspiring and fearsome. It is also interspersed with editorial interpretations, genealogies, and long lists of priestly regulations, moral codes, and instructions for building the portable religious sanctuary, or tabernacle, which the Israelites carried through the wilderness. The story of the Exodus does not end with the Book of Exodus, but continues and overlaps with other biblical books including Numbers, Leviticus, and Deuteronomy.

Background

The later chapters of Genesis describe a famine in Canaan and the migration of the sons of Jacob and their clans to Egypt, where they settle under the protection of their brother Joseph, who had become the prime minister of that land. There, the Israelites multiply and become strong, "so that the land was filled with them."

The Book of Exodus opens as a new Pharaoh, "who knew not Joseph," becomes concerned about the military implications of the large increase in the Israelite population. He enslaves them and allows them only manual labor. He then takes the drastic measure of ordering the Hebrew midwives to kill all male babies.

The birth, exile, and call of Moses

A Levite woman, later identified as Jochebed, the wife of Amram (6:20), avoids this fate for her son by placing him in a reed basket that she floats down the Nile. A daughter of the king of Egypt finds the infant, calling him Moses (related to "drawn out," from the Hebrew, but also related to the Egyptian word for "son"). After his own mother serves as wet nurse to the child, Moses is brought up as an Egyptian prince. When he becomes a man, he takes sympathy for one of the Hebrew laborers who is being whipped by his overlord. Moses kills the Egyptian oppressor and buries his body in the sand. Worse, the Hebrews themselves view his act as a threat and begin to spread the news of his deed.

To escape from Pharaoh, who seeks his life, Moses flees the country. Moses' exile takes him to Midian, where he becomes shepherd to the priest Jethro (here called Reuel) and marries his daughter, Zipporah. As he feeds the sheep on Mount Horeb, God beckons Moses from a burning bush. In one of the Bible's most memorable scenes, God reveals his true name of Yahweh, and orders Moses to return to Egypt to demand the release of the Israelites from Pharaoh. Moses at first demurs, saying the Israelites will not believe him, but God gives him the power to perform miraculous signs to show his authority. Moses still hesitates, and God's "anger burned against Moses." Aaron, mentioned now for the first time and identified as Moses' older brother, is appointed to assist him. On his return to Egypt, apparently still angry, God tries to kill Moses, but Zipporah circumcises Moses' son, thus saving Moses' life. (2-4)

The plagues and the Passover

God calls Aaron and sends him to meet Moses in the wilderness. Aaron gives God's message to the Israelites and performs miracles. The people believe.

Moses meets with the Egyptian ruler and, in Yahweh's name, demands permission to go on a three-day pilgrimage into the desert to hold a sacred feast. The king not only refuses, but oppresses the people still further, accusing them of laziness and ordering them to gather their own straw to make bricks without diminishing the quota. Moses complains to God that his ministry is only resulting in increased suffering for the Israelites. God identifies himself again to Moses, this time explaining that Moses is the first of the Israelites to know his true name, which was unrevealed even to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. God promises that he will redeem Israel "with an outstretched arm and with mighty acts of judgment."

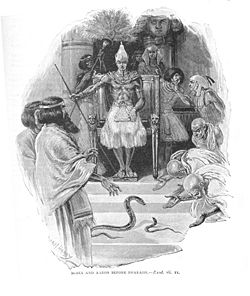

God then sends a series of miraculous but terrible plagues onto Egypt. First, Aaron throws down his staff, and it becomes a snake. The kings magicians, however, perform the same feat. But Aaron's snake swallows the Egyptian serpents, but this only hardens the heart of the king against the Israelites. Next Aaron turns the Nile to blood, killing its fish. Again, the Egyptian magicians accomplish the same feat, and again Pharaoh refuses to relent. Aaron then causes frogs to emerge from the Nile to plague the land. The Egyptian magicians do the same. This time Pharaoh asks Moses to pray to Yahweh to take the frogs away. God responds to Moses' entreaty, but the king again hardens his heart. Aaron now performs a miracle that the Egyptians cannot duplicate: a plague of gnats. The magicians testify, "this is the finger of God," but Pharaoh stubbornly refuses to listen.

The pattern of miracles now shifts away from Aaron. Moses threatens the king with a plague of flies, and God directly brings it about. The country is so devastated by this catastrophe, that Pharaoh finally agrees that the Israelites may make their pilgrimage if Moses will ask Yahweh to take away the flies. Moses does so, but Pharaoh, of course, changes his mind once again. Next comes a plague that kills Egyptian livestock but spares the Israelite cattle. Then Moses brings about a plague of boils. Even the Egyptian magicians are sorely afflicted by the disease, but the king stubbornly refuses to give in. Next God tells Moses to threaten a mighty hailstorm. Some of the Egyptians respond to the warning and move their cattle to shelter. The remainder are devastated by the storm, while the Israelite areas remain untouched. Pharaoh actually admits his sin this time and promises to let the people go, but once again changes his mind after the hail stops.

The Egyptian courtiers lobby to let the Israelites have their festival, and the king begins to negotiate with Moses. Suspecting a trick, Pharaoh agrees to let the men make their pilgrimage but not the Israelite women and children. God and Moses respond with a plague of locusts that devour the crops not already destroyed by the hail. Once again Pharaoh begs for forgiveness, Moses removes the plague and Pharaoh hardens his heart. God then plagues Egypt with three days of darkness. His will now almost broken, Pharaoh agrees that the women and children can join the pilgrimage, but not the cattle. Moses refuses to negotiate, and God hardens the king's heart one last time.

Finally, God sends a truly horrendous plague, killing all the Egyptian firstborn. On his way to carry out the task, Yahweh passes over the houses of the Israelites, recognizing them by lamb's blood that Moses has ordered painted on each Hebrew home's door post. The narrator explains that this event provides the background for the holiday of Passover, which the Israelites are to commemorate each year. (12:42) The king finally truly relents and allows the Israelites to leave for their supposed three-day pilgrimage. The Egyptians send them on their way with gifts of gold and jewelry. (4-12)

The journey to Mount Sinai

The Exodus thus begins, and Moses informs the Israelites that the plan is to go all the way to Canaan, a "land flowing with milk and honey." Pharaoh, confirming his suspicion that the Israelites have fled, gathers a large army to pursue them. The Israelites, led by a majestic pillar of fire by night and a pillar of cloud by day, have now reached the "Reed Sea" (Yam Suph—often mistranslated as the Red Sea).

In one of the Bible's most dramatic moments, Moses causes the waters of the sea to part, and the Israelites cross over on dry land. The waters collapse once the Israelites have passed, defeating Pharaoh and drowning his army. The prophetess Miriam, Moses' sister, leads the Israelites as they joyfully dance and sing what scholars consider to be one of the oldest verses in the Bible:

- Sing to the Lord,

- for he is highly exalted.

- The horse and its rider

- he has hurled into the sea. (15:21)

The Israelites continue their journey into the desert, and once in the Wilderness of Sin, they complain about the lack of food. Listening to their complaint, God sends them a large quantity of low-flying quail, and subsequently provides a daily ration of manna. Once at Rephidim, thirst torments the people, and water is miraculously provided from a rock. However, a troubling pattern has emerged, as the Israelites display a lack of trust in Moses and seek to "put God to the test." (17:2) Soon a tribe known as the Amalekites attack. The newly emergent military hero Joshua manages to vanquish them, and God orders an eternal war against Amalek until they are utterly obliterated. (Indeed, the Amalekites are a tribe unknown to history outside of the Bible.) In Midian, Zipporah's father Jethro hears of Moses' approach and visits him. Although not an Israelite, but a Midanite priest, he "offers sacrifices to God" and eats a sacred meal with "elders of Israel in God's presence." (18:12) Jethro also advises Moses to appoint judges to assist in the administration of tribal affairs, and "Moses listened to his father-in-law and did everything that he said to do. (18:24)

The Covenant and its Laws

In the third month, the Israelites arrive at Mount Sinai, and God declares, via Moses, that the Israelites are God's people, as He has liberated them by His power. The Israelites agree to a covenant of obedience with Yahweh, and so, with thunder and lightning, clouds of smoke, and the noise of a mighty trumpet, God appears to them in a cloud at the top of the mountain. (19)

God then declares a version of the Ten Commandments, sometimes referred to as the Moral Decalogue (20). A series of laws governing the rights and limits of slavery follow this. Capital punishment is enacted for murder, kidnapping, and attacking or cursing one's parents. Other personal injury and property laws are also enacted. (21-22) The death sentence is also imposed on women convicted of sorcery. Bestiality likewise is punishable by death, as is the offering of sacrifices to gods other than Yahweh.

Aliens and orphans, however, are to be protected. Usury, blasphemy, and the cursing of one's ruler are prohibited. God requires that first-born sons and cattle be offered to Him on the eighth day after their birth. Cattle that die after being attacked by wild beasts must not be eaten. False witness and bribery are prohibited. Every seventh year, a field must be left uncultivated by their owner so that the poor may gain food from it. The sabbath must be observed every seventh day, and both slaves and livestock must be allowed to rest then as well. Various festival and ritual laws are enacted, including the prohibition against cooking a young goat in its mother's milk, the root of the later Jewish tradition of Kashrut, which involves never mixing milk and meat dishes.

Finally, God promises the Israelites if they obey, he will fight for them against the Canaanites, establishing their borders "from the Yam Suph to the Sea of the Philistines (the Mediterranean), and from the desert to the (Euphrates) River." Covenants and coexistence with the Canaanites are prohibited. (23)

Moses then erects 12 stone pillars at the base of the sacred mountain, representing each of the Tribes of Israel. He seals the Israelites' covenant with Yahweh by sprinkling the congregation with the blood of a bull calf he has sacrificed. He then reads to them what he has written thus far in the "Book of the Covenant," and the people swear to obey its commandments.

Setting out with Joshua, Moses then ascends the mountain again, leaving Aaron and Hur in charge of those remaining behind. He would be on the mountain for 40 days. (24)

The Tabernacle, vestments, and ritual objects (25-31)

While Moses is on the mountain, Yahweh gives him detailed instructions regarding the construction of the tabernacle, a portable sanctuary in which God can dwell permanently among the Israelites. Elements include:

- The Ark of the Covenant, to contain the tablets of the Ten Commandments

- A mercy seat, with two golden cherubim on either side, serving as a throne for Yahweh.

- A menorah, never to be extinguished.

- A portable structure to contain these things.

- An outer court, involving pillars on bronze pedestals.

Instructions are also given for the garments of the priests:

- An ephod of gold, attached to two ornate shoulder-pieces. It is to contain two onyx stones, each engraved with the names of six of the tribes of Israel.

- A breastplate containing Urim and Thummim for divination.

- Golden chains for holding the breastplate set with 12 specific precious stones, in four rows.

- A blue cloth robe with pomegranate-shaped tassels and bells around its seams.

- A coat, girdle, tunic, sash, headband, and linen undergarments.

- A mitre with a golden plate with the inscription Holy to the Lord.

Following these instructions God specifies the ritual to be used to ordain the priests, including robing, anointing, and seven days of sacrifices. Instructions are also provided for morning and evening offerings of a lamb (29). Additional tabernacle instructions follow, involving the making of a golden altar of incense, laver, anointing oil, and perfume. A half-shekel offering is required by God of rich and poor alike as a "ransom" for their lives. (30) Bezaleel and Aholiab are identified as the craftsmen to construct these things. The sabbath is again emphasized, with the death penalty specified as the punishment for anyone convicted of working on this sacred day of rest. (31) Finally:

- When the Lord finished speaking to Moses on Mount Sinai, he gave him the two tablets of the Testimony, the tablets of stone inscribed by the finger of God. (31:18)

The golden calf

While Moses is up the mountain, however, the people become impatient and urge Aaron to fashion an icon for their worship. He collects their golden jewelry and fashions a bull-calf, proclaiming "Here is God,(elohim) who brought you out of Egypt." (Elohim, is normally translated as God, but here is usually translated as "gods.") The Israelites offer sacrifice, followed by a feast and joyous celebration.

Yahweh, however, is offended and informs Moses that the people have become idolatrous. He intends to destroy the Israelites, but promises He will make of Moses a "great nation." Moses appeals to God's reputation among the Egyptians and His promise to the Hebrew patriarchs, and God relents. However, when Moses comes down from the mountain and sees the revelry, he becomes enraged and smashes the two sacred tablets of the Law, which had been inscribed with "the writing of God." Grinding the golden bull-calf to dust, mixing this with water, and making the people drink of it, Moses strongly reprimands Aaron. He then rallies his fellow Levites to his side and institutes a slaughter of the rebels, with a reported 3,000 of them killed. Moses then implores God to forgive the remaining people but wins for them only a temporary reprieve. God strikes the congregation with a plague, and promises even heavier punishment in the future.(32)

The strained relationship between God and his people is apparent. With the tabernacle as yet unconstructed, Moses builds a tent in which he meets God "face to face, as a man speaks with his friend." Joshua stays on vigil in the tent when Moses returns to the camp.

Moses consequently is commanded to make two new tablets and ascend the mountain once again. God appears to Moses in dramatic fashion there, saying:

- Yahweh! Yahweh! The compassionate and gracious God, slow to anger, abounding in love and faithfulness, maintaining love to thousands, and forgiving wickedness, rebellion and sin. Yet he does not leave the guilty unpunished; he punishes the children and their children for the sin of the fathers to the third and fourth generation. (34:6-7)

Moses intercedes again on behalf of the people and God renews his covenant with them, once again giving the Ten Commandments. This version is sometimes called the Ritual Decalogue because it adds a number of specifications regarding the celebration of Passover, other holidays, and sacrificial offerings. Moses then returns to the people, his face blindingly radiant, and conveys the words of the covenant to them once again. (34)

Construction of the tabernacle

Moses collects the congregation, impresses upon them the crucial importance of keeping the sabbath, and requests gifts for the tabernacle sanctuary. The entire people respond willingly.

Under the direction of the master craftsmen Bezaleel and Aholiab, they complete all the instructions for making the tabernacle and its contents, including the sacred Ark of the Covenant. As in the earlier description of the tabernacle and its contents, no detail is spared. Indeed, chapters 35-40 appear to be largely rehearsed from the earlier section. The tabernacle, far from being a mere tent which housed the Ark, is described as a richly ornate structure with secure but portable foundations of pure silver, collected from the required half-shekel offerings of 603,000 men, making the total number of people probably more than two million.(38)

The sin of Aaron seems to be completely forgotten as he and his sons are solemnly consecrated as priests, clothed in the rich sacred garments painstakingly prepared to confer honor and holiness upon them. Then, "the glory of the Lord filled the tabernacle."

The Book of Exodus thus ends on a high note, with the people finally having united faithfully to accomplish God's will, and Yahweh descended to earth to dwell among His people in the tabernacle. God leads them directly, and all seems, for the moment, to be right with the world:

In all the travels of the Israelites, whenever the cloud lifted from above the tabernacle, they would set out; but if the cloud did not lift, they did not set out—- until the day it lifted. So the cloud of the Lord was over the tabernacle by day, and fire was in the cloud by night, in the sight of all the house of Israel during all their travels. (40:36-38)

Authorship

As with the other books of the Torah, both Orthodox Judaism and Christianity hold that the text of Exodus was dictated to Moses by God Himself. Modern biblical scholarship, however, regards the text as being compiled either during the Kingdom of Judah (seventh c. B.C.E.) or during post-exilic times (sixth or fifth century B.C.E.). However, it is generally agreed that much of the material in Exodus is older than this, some of it probably reflecting authentic, if exaggerated, memories.

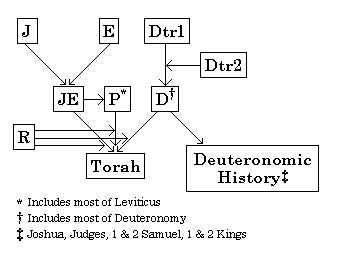

The documentary hypothesis postulates that there were several, post-Moses, authors of the written sources in Exodus, whose stories have been intertwined by a later editor/compiler. The three main authors of the work are said, in this hypothesis, to be the Yahwist (J), Elohist (E), and Priestly source (P). In addition, the poetic Song of the Sea and the prose Covenant Code are thought to have been originally independent works that one of the above writers included in his saga.

Evidence for multiple authors can be seen in such facts as Zipporah's father being called "Ruel" in come chapters and "Jethro" in others, as well as the sacred mountain of God being called "Horeb" by one putative source and "Sinai" by another. Moreover, God's calling of Moses appears to happen several times in the story, as we have it. Several repetitions and false starts appear. A genealogy, clearly written long after Moses' death, suddenly appears in chapter 6, breaking up the flow of the story. There are even two different versions of the Ten Commandments, with a third version appearing in Deuteronomy, all supposedly written by God through Moses.

Regarding the latter, the Priestly source is credited with the Ethical Decalogue, and the Yahwist with the Ritual Decalogue, and the Deuteronomist, fittingly receives credit for the version in his particular book.

Many parts of Exodus are believed to have been constructed by intertwining the Yahwist, Elohist, and Priestly versions of the various stories. Deconstructions of the stories into these sources identify heavy variations between stories. For example, the "P"" never provides a warning to Pharaoh about the plagues and always involves Aaron—the archetype of priesthood. The Elohist (E) always provides a warning to Pharaoh and hardly ever portrays Aaron in a positive light. The Yahwist (J) portrays God as a mercurial deity prone to fits of anger, needing the wise counsel of Moses to see the correct course. The Elohist is the likely author of the story of God meeting face to face with Moses in the tent of meeting (33). In the same chapter, the Yahwist quotes the Lord as declaring to Moses: "you cannot see my face, for no one may see me and live." (33:19)

The Elohist, being the least friendly toward Aaron, is identified as responsible for the episode of the golden calf. A question also exists as to whether this episode was truly historical or represents a propandistic attack on a later era's "idolatrous" shine featuring a bull calf at Bethel. It is seen as more than mere coincidence that King Jeroboam I, at Bethel, is represented as declaring the exact blasphemous words that Aaron utters: "here is elohim." Scholars also marvel at the apparent double standard of God in forbidding graven images in one chapter (20:4), while commanding the creation of two solid gold cherubim statues in another (25:18), not to mention ordering the creation of a bronze serpent in the Book of Numbers (28:8-9).

The Yahwist, in contrast to the Elohist's criticism of Aaron, portrays God as so angry with Moses as to attempt to murder him. The heroine in this episode being Zipporah—together with the Yahwist's many other strong female characters—has led some to speculate that the author of "J" may have herself been a woman, probably living in the ninth century B.C.E. (Bloom 2005).

A particularly interesting episode is the revelation of God's name, Yahweh, to Moses for the first time in Exodus 6:3. This story, thought to be from "P" and designed to explain why God has also been called "El Shaddai" or "Elohim" in previous writings, contradicts several earlier Yahwist affirmations in the Book of Genesis (4:6, 12:8, etc.) that the patriarchs called on "the name of Yahweh."

The Priestly source, of course, is seen as responsible for the instructions about creating the tabernacle, vestments, and ritual objects. The final chapters of Exodus, in which Aaron is uplifted and God descends to dwell in the tabernacle, thus reflect the viewpoint of the Temple scribes who ultimately committed the story to writing.

The historicity of the events in the Book of Exodus are discussed in the article on The Exodus.

See also

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Albright, W.F. 2006. Archaeology and the Religion of Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0664227425.

- Bloom, Harold. 2005. The Book of J. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 0802141919

- Dever, William. 2006. Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802844163

- Finkelstein, Israel. 2002. The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. New York: Free Press. ISBN 0684869136

- Humphreys Colin J. 2006. The Miracles of Exodus: A Scientist’s Discovery of the Extraordinary Natural Causes of the Biblical Stories. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0826480262

- Sabbah, Messod, et al. 2004. Secrets of the Exodus: The Egyptian Origins of the Hebrew People. New York, NY: Allworth Press. ISBN 978-1581153194.

- Sarna, Nahum. 1996. Exploring Exodus: The Origins of Biblical Israel. Shocken Books/Random House. ISBN 978-0805210637.

External links

All links retrieved August 9, 2017.

- Kaplan, Rabbi Aryeh. trans., "Exodus", navigating the Bible II.

- Shemot - "Judaica Press Complete Tanach Shemot - Exodus", Chabad.org Library.

|

|||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 03:02:20 | 197 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Exodus,_Book_of | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF