Stomach Cancer

From Mdwiki

From Mdwiki | Stomach cancer | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Gastric cancer | |

| |

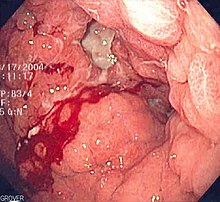

| A stomach ulcer that was diagnosed as cancer on biopsy and surgically removed | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

| Symptoms | Early: Heartburn, upper abdominal pain, nausea, loss of appetite.[1] Later: Weight loss, yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes, vomiting, difficulty swallowing, blood in the stool[1] |

| Usual onset | Over years[2] |

| Types | Gastric carcinomas, lymphoma, mesenchymal tumor[2] |

| Causes | Helicobacter pylori, genetics[2][3] |

| Risk factors | Smoking, dietary factors such as pickled vegetables, obesity[2][4] |

| Diagnostic method | Biopsy done during endoscopy[1] |

| Prevention | Mediterranean diet, stopping smoking[2][5] |

| Treatment | Surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, targeted therapy[1] |

| Prognosis | Five-year survival rate: < 10% (advanced cases),[6] 32% (US),[7] 71% (Japan)[8] |

| Frequency | 3.5 million (2015)[9] |

| Deaths | 783,000 (2018)[10] |

Stomach cancer, also known as gastric cancer, is a cancer that develops from the lining of the stomach.[11] Most cases of stomach cancers are gastric carcinomas, which can be divided into a number of subtypes including gastric adenocarcinomas.[2] Lymphomas and mesenchymal tumors may also develop in the stomach.[2] Early symptoms may include heartburn, upper abdominal pain, nausea and loss of appetite.[1] Later signs and symptoms may include weight loss, yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes, vomiting, difficulty swallowing and blood in the stool among others.[1] The cancer may spread from the stomach to other parts of the body, particularly the liver, lungs, bones, lining of the abdomen and lymph nodes.[12]

The most common cause is infection by the bacterium Helicobacter pylori, which accounts for more than 60% of cases.[2][3][13] Certain types of H. pylori have greater risks than others.[2] Smoking, dietary factors such as pickled vegetables and obesity are other risk factors.[2][4] About 10% of cases run in families, and between 1% and 3% of cases are due to genetic syndromes inherited from a person's parents such as hereditary diffuse gastric cancer.[2] Most of the time, stomach cancer develops in stages over years.[2] Diagnosis is usually by biopsy done during endoscopy.[1] This is followed by medical imaging to determine if the disease has spread to other parts of the body.[1] Japan and South Korea, two countries that have high rates of the disease, screen for stomach cancer.[2]

A Mediterranean diet lowers the risk of stomach cancer, as does the stopping of smoking.[2][5] There is tentative evidence that treating H. pylori decreases the future risk.[2][5] If stomach cancer is treated early, it can be cured.[2] Treatments may include some combination of surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy and targeted therapy.[1][14] If treated late, palliative care may be advised.[2] Some types of lymphoma can be cured by eliminating H. pylori.[15] Outcomes are often poor, with a less than 10% five-year survival rate in the Western world for advanced cases.[6] This is largely because most people with the condition present with advanced disease.[6] In the United States, five-year survival is 31.5%,[7] while in South Korea it is over 65% and Japan over 70%, partly due to screening efforts.[2][8]

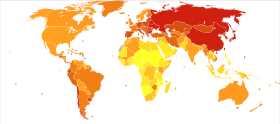

Globally, stomach cancer is the fifth leading type of cancer and the third leading cause of death from cancer, making up 7% of cases and 9% of deaths.[16] In 2018, it newly occurred in 1.03 million people and caused 783,000 deaths.[10] Before the 1930s, in much of the world, including most Western developed countries, it was the most common cause of death from cancer.[17][18] Rates of death have been decreasing in many areas of the world since then.[2] This is believed to be due to the eating of less salted and pickled foods as a result of the development of refrigeration as a method of keeping food fresh.[19] Stomach cancer occurs most commonly in East Asia and Eastern Europe.[2] It occurs twice as often in males as in females.[2]

Signs and symptoms[edit | edit source]

Stomach cancer is often either asymptomatic (producing no noticeable symptoms) or it may cause only nonspecific symptoms (symptoms that may also be present in other related or unrelated disorders) in its early stages. By the time symptoms occur, the cancer has often reached an advanced stage (see below) and may have metastasized (spread to other, perhaps distant, parts of the body), which is one of the main reasons for its relatively poor prognosis.[20] Stomach cancer can cause the following signs and symptoms:

Early cancers may be associated with indigestion or a burning sensation (heartburn). However, fewer than 1 in every 50 people referred for endoscopy due to indigestion has cancer.[21] Abdominal discomfort and loss of appetite, especially for meat, can occur.

Gastric cancers that have enlarged and invaded normal tissue can cause weakness, fatigue, bloating of the stomach after meals, abdominal pain in the upper abdomen, nausea and occasional vomiting, diarrhea or constipation. Further enlargement may cause weight loss or bleeding with vomiting blood or having blood in the stool, the latter apparent as black discolouration (melena) and sometimes leading to anemia. Dysphagia suggests a tumour in the cardia or extension of the gastric tumour into the esophagus.

These can be symptoms of other problems such as a stomach virus, gastric ulcer, or tropical sprue.

Risk factors[edit | edit source]

Gastric cancer can occur as a result of many factors.[22] It occurs twice as commonly in males as females. Estrogen may protect women against the development of this form of cancer.[23][24]

Infections[edit | edit source]

Helicobacter pylori infection is an essential risk factor in 65–80% of gastric cancers, but only 2% of people with Helicobacter infections develop stomach cancer.[4][25] The mechanism by which H. pylori induces stomach cancer potentially involves chronic inflammation, or the action of H. pylori virulence factors such as CagA.[26] It was estimated that Epstein–Barr virus is responsible for 84,000 cases per year.[27] AIDS is also associated with elevated risk.[4]

Smoking[edit | edit source]

Smoking increases the risk of developing gastric cancer significantly, from 40% increased risk for current smokers to 82% increase for heavy smokers. Gastric cancers due to smoking mostly occur in the upper part of the stomach near the esophagus.[28][29][30] Some studies show increased risk with alcohol consumption as well.[4][31]

Diet[edit | edit source]

Dietary factors are not proven causes, and the association between stomach cancer and various foods and beverages is weak.[33] Some foods including smoked foods, salt and salt-rich foods, red meat, processed meat, pickled vegetables, and bracken are associated with a higher risk of stomach cancer.[4][34][35] Nitrates and nitrites in cured meats can be converted by certain bacteria, including H. pylori, into compounds that have been found to cause stomach cancer in animals.

Fresh fruit and vegetable intake, citrus fruit intake, and antioxidant intake are associated with a lower risk of stomach cancer.[4][28] A Mediterranean diet is associated with lower rates of stomach cancer,[36] as is regular aspirin use.[4]

Obesity is a physical risk factor that has been found to increase the risk of gastric adenocarcinoma by contributing to the development of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).[37] The exact mechanism by which obesity causes GERD is not completely known. Studies hypothesize that increased dietary fat leading to increased pressure on the stomach and the lower esophageal sphincter, due to excess adipose tissue, could play a role, yet no statistically significant data has been collected.[38] However, the risk of gastric cardia adenocarcinoma, with GERD present, has been found to increase more than 2 times for an obese person.[37] There is a correlation between iodine deficiency and gastric cancer.[39][40][41]

Genetics[edit | edit source]

About 10% of cases run in families and between 1% and 3% of cases are due to genetic syndromes inherited from a person's parents such as hereditary diffuse gastric cancer.[2]

A genetic risk factor for gastric cancer is a genetic defect of the CDH1 gene known as hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (HDGC). The CDH1 gene, which codes for E-cadherin, lies on the 16th chromosome.[42] When the gene experiences a particular mutation, gastric cancer develops through a mechanism that is not fully understood.[42] This mutation is considered autosomal dominant meaning that half of a carrier's children will likely experience the same mutation.[42] Diagnosis of hereditary diffuse gastric cancer usually takes place when at least two cases involving a family member, such as a parent or grandparent, are diagnosed, with at least one diagnosed before the age of 50.[42] The diagnosis can also be made if there are at least three cases in the family, in which case age is not considered.[42]

The International Cancer Genome Consortium is leading efforts to identify genomic changes involved in stomach cancer.[43][44] A very small percentage of diffuse-type gastric cancers (see Histopathology below) arise from an inherited abnormal CDH1 gene. Genetic testing and treatment options are available for families at risk.[45]

Other[edit | edit source]

Other risks include diabetes,[46] pernicious anemia,[31] chronic atrophic gastritis,[47] Menetrier's disease (hyperplastic, hypersecretory gastropathy),[48] and intestinal metaplasia.[49]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

To find the cause of symptoms, the doctor asks about the patient's medical history, does a physical exam, and may order laboratory studies. The patient may also have one or all of the following exams:

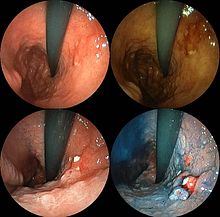

- Gastroscopic exam is the diagnostic method of choice. This involves insertion of a fibre optic camera into the stomach to visualise it.[31]

- Upper GI series (may be called barium roentgenogram).

- Computed tomography or CT scanning of the abdomen may reveal gastric cancer. It is more useful to determine invasion into adjacent tissues or the presence of spread to local lymph nodes. Wall thickening of more than 1 cm that is focal, eccentric and enhancing favours malignancy.[50]

In 2013, Chinese and Israeli scientists reported a successful pilot study of a breathalyzer-style breath test intended to diagnose stomach cancer by analyzing exhaled chemicals without the need for an intrusive endoscopy.[51] A larger-scale clinical trial of this technology was completed in 2014.[52]

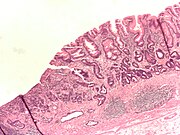

Abnormal tissue seen in a gastroscope examination will be biopsied by the surgeon or gastroenterologist. This tissue is then sent to a pathologist for histological examination under a microscope to check for the presence of cancerous cells. A biopsy, with subsequent histological analysis, is the only sure way to confirm the presence of cancer cells.[31]

Various gastroscopic modalities have been developed to increase yield of detected mucosa with a dye that accentuates the cell structure and can identify areas of dysplasia. Endocytoscopy involves ultra-high magnification to visualise cellular structure to better determine areas of dysplasia. Other gastroscopic modalities such as optical coherence tomography are being tested investigationally for similar applications.[53]

A number of cutaneous conditions are associated with gastric cancer. A condition of darkened hyperplasia of the skin, frequently of the axilla and groin, known as acanthosis nigricans, is associated with intra-abdominal cancers such as gastric cancer. Other cutaneous manifestations of gastric cancer include tripe palms (a similar darkening hyperplasia of the skin of the palms) and the Leser-Trelat sign, which is the rapid development of skin lesions known as seborrheic keratoses.[54]

Various blood tests may be done including a complete blood count (CBC) to check for anaemia, and a fecal occult blood test to check for blood in the stool.

Histopathology[edit | edit source]

- Gastric adenocarcinoma is a malignant epithelial tumour, originating from glandular epithelium of the gastric mucosa. Stomach cancers are about 90% adenocarcinomas.[55] Histologically, there are two major types of gastric adenocarcinoma (Lauren classification): intestinal type or diffuse type. Adenocarcinomas tend to aggressively invade the gastric wall, infiltrating the muscularis mucosae, the submucosa and then the muscularis propria. Intestinal type adenocarcinoma tumour cells describe irregular tubular structures, harbouring pluristratification, multiple lumens, reduced stroma ("back to back" aspect). Often, it associates intestinal metaplasia in neighbouring mucosa. Depending on glandular architecture, cellular pleomorphism and mucosecretion, adenocarcinoma may present 3 degrees of differentiation: well, moderate and poorly differentiated. Diffuse type adenocarcinoma (mucinous, colloid, linitis plastica or leather-bottle stomach) tumour cells are discohesive and secrete mucus, which is delivered in the interstitium, producing large pools of mucus/colloid (optically "empty" spaces). It is poorly differentiated. If the mucus remains inside the tumour cell, it pushes the nucleus to the periphery: "signet-ring cell".

- Around 5% of gastric cancers are lymphomas.[56] These may include extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphomas (MALT type)[57] and to a lesser extent diffuse large B-cell lymphomas.[58] MALT type make up about half of stomach lymphomas.[15]

- Carcinoid and stromal tumors may occur.

-

Poor to moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma of the stomach. H&E stain.

-

Gastric signet ring cell carcinoma. H&E stain.

-

Adenocarcinoma of the stomach and intestinal metaplasia. H&E stain.

Staging[edit | edit source]

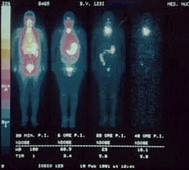

If cancer cells are found in the tissue sample, the next step is to stage, or find out the extent of the disease. Various tests determine whether the cancer has spread and, if so, what parts of the body are affected. Because stomach cancer can spread to the liver, the pancreas, and other organs near the stomach as well as to the lungs, the doctor may order a CT scan, a PET scan,[59] an endoscopic ultrasound exam, or other tests to check these areas. Blood tests for tumor markers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen (CA) may be ordered, as their levels correlate to extent of metastasis, especially to the liver, and the cure rate.

Staging may not be complete until after surgery. The surgeon removes nearby lymph nodes and possibly samples of tissue from other areas in the abdomen for examination by a pathologist.

The clinical stages of stomach cancer are:[60][61]

- Stage 0. Limited to the inner lining of the stomach. Treatable by endoscopic mucosal resection when found very early (in routine screenings); otherwise by gastrectomy and lymphadenectomy without need for chemotherapy or radiation.

- Stage I. Penetration to the second or third layers of the stomach (Stage 1A) or to the second layer and nearby lymph nodes (Stage 1B). Stage 1A is treated by surgery, including removal of the omentum. Stage 1B may be treated with chemotherapy (5-fluorouracil) and radiation therapy.

- Stage II. Penetration to the second layer and more distant lymph nodes, or the third layer and only nearby lymph nodes, or all four layers but not the lymph nodes. Treated as for Stage I, sometimes with additional neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

- Stage III. Penetration to the third layer and more distant lymph nodes, or penetration to the fourth layer and either nearby tissues or nearby or more distant lymph nodes. Treated as for Stage II; a cure is still possible in some cases.

- Stage IV. Cancer has spread to nearby tissues and more distant lymph nodes, or has metastasized to other organs. A cure is very rarely possible at this stage. Some other techniques to prolong life or improve symptoms are used, including laser treatment, surgery, and/or stents to keep the digestive tract open, and chemotherapy by drugs such as 5-fluorouracil, cisplatin, epirubicin, etoposide, docetaxel, oxaliplatin, capecitabine or irinotecan.[14]

The TNM staging system is also used.[62]

In a study of open-access endoscopy in Scotland, patients were diagnosed 7% in Stage I 17% in Stage II, and 28% in Stage III.[63] A Minnesota population was diagnosed 10% in Stage I, 13% in Stage II, and 18% in Stage III.[64] However, in a high-risk population in the Valdivia Province of southern Chile, only 5% of patients were diagnosed in the first two stages and 10% in stage III.[65]

Prevention[edit | edit source]

Getting rid of H. pylori in those who are infected decreases the risk of stomach cancer, at least in those who are Asian.[66] A 2014 meta-analysis of observational studies found that a diet high in fruits, mushrooms, garlic, soybeans, and green onions was associated with a lower risk of stomach cancer in the Korean population.[67] Low doses of vitamins, especially from a healthy diet, decrease the risk of stomach cancer.[68] A previous review of antioxidant supplementation did not find supporting evidence and possibly worse outcomes.[69][70]

Management[edit | edit source]

Cancer of the stomach is difficult to cure unless it is found at an early stage (before it has begun to spread). Unfortunately, because early stomach cancer causes few symptoms, the disease is usually advanced when the diagnosis is made.[72]

Treatment for stomach cancer may include surgery,[73] chemotherapy,[14] or radiation therapy.[74] New treatment approaches such as immunotherapy or gene therapy and improved ways of using current methods are being studied in clinical trials.[75]

Surgery[edit | edit source]

Surgery remains the only curative therapy for stomach cancer.[6] Of the different surgical techniques, endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) is a treatment for early gastric cancer (tumor only involves the mucosa) that was pioneered in Japan and is available in the United States at some centers.[6] In this procedure, the tumor, together with the inner lining of stomach (mucosa), is removed from the wall of the stomach using an electrical wire loop through the endoscope. The advantage is that it is a much smaller operation than removing the stomach.[6] Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is a similar technique pioneered in Japan, used to resect a large area of mucosa in one piece.[6] If the pathologic examination of the resected specimen shows incomplete resection or deep invasion by tumor, the patient would need a formal stomach resection.[6] A 2016 Cochrane review found low quality evidence of no difference in short-term mortality between laparoscopic and open gastrectomy (removal of stomach), and that benefits or harms of laparoscopic gastrectomy cannot be ruled out.[76] Post-operatively, up to 70% of people undergoing total gastrectomy develop complications such as dumping syndrome and reflux esophagitis.[77] Construction of a "pouch", which serves as a "stomach substitute", reduced the incidence of dumping syndrome and reflux esophagitis by 73% and 63% respectively, and led to improvements in quality-of-life, nutritional outcomes, and body mass index.[77]

Those with metastatic disease at the time of presentation may receive palliative surgery and while it remains controversial, due to the possibility of complications from the surgery itself and the fact that it may delay chemotherapy the data so far is mostly positive, with improved survival rates being seen in those treated with this approach.[6][78]

Chemotherapy[edit | edit source]

The use of chemotherapy to treat stomach cancer has no firmly established standard of care.[14] Unfortunately, stomach cancer has not been particularly sensitive to these drugs, and chemotherapy, if used, has usually served to palliatively reduce the size of the tumor, relieve symptoms of the disease and increase survival time.[14] Some drugs used in stomach cancer treatment have included: 5-FU (fluorouracil) or its analog capecitabine, BCNU (carmustine), methyl-CCNU (semustine) and doxorubicin (Adriamycin), as well as mitomycin C, and more recently cisplatin and taxotere, often using drugs in various combinations.[14] The relative benefits of these different drugs, alone and in combination, are unclear.[79][14] Clinical researchers are exploring the benefits of giving chemotherapy before surgery to shrink the tumor, or as adjuvant therapy after surgery to destroy remaining cancer cells.[6]

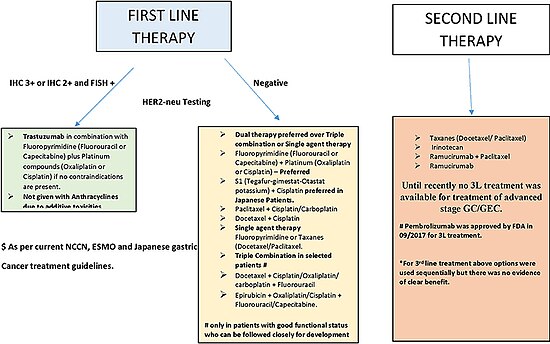

Targeted therapy[edit | edit source]

Recently, treatment with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) inhibitor, trastuzumab, has been demonstrated to increase overall survival in inoperable locally advanced or metastatic gastric carcinoma over-expressing the HER2/neu gene.[6] In particular, HER2 is overexpressed in 13–22% of patients with gastric cancer.[75][80] Of note, HER2 overexpression in gastric neoplasia is heterogeneous and comprises a minority of tumor cells (less than 10% of gastric cancers overexpress HER2 in more than 5% of tumor cells). Hence, this heterogeneous expression should be taken into account for HER2 testing, particularly in small samples such as biopsies, requiring the evaluation of more than one bioptic sample.[80]

Radiation[edit | edit source]

Radiation therapy (also called radiotherapy) may be used to treat stomach cancer, often as an adjuvant to chemotherapy and/or surgery.[6]

Lymphoma[edit | edit source]

Lymphoma of the MALT type can often be fully treated by treating an underlying H. pylori infection.[15] This results in remission in about 80% of cases.[15]

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

The prognosis of stomach cancer is generally poor, due to the fact the tumour has often metastasised by the time of discovery and the fact that most people with the condition are elderly (median age is between 70 and 75 years) at presentation.[81] The average life expectancy after being diagnosed is around 24 months, and the five-year survival rate for stomach cancer is less than 10 percent.[6]

Almost 300 genes are related to outcomes in stomach cancer with both unfavorable genes where high expression related to poor survival and favorable genes where high expression associated with longer survival times.[82][83] Examples of poor prognosis genes include ITGAV, DUSP1 and P2RX7. [84]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Worldwide, stomach cancer is the fifth most-common cancer with 952,000 cases diagnosed in 2012.[16] It is more common both in men and in developing countries.[85][86] In 2012, it represented 8.5% of cancer cases in men, making it the fourth most-common cancer in men.[87] Also in 2012, the number of deaths was 700,000 having decreased slightly from 774,000 in 1990, making it the third-leading cause of cancer-related death (after lung cancer and liver cancer).[88][89]

Less than 5% of stomach cancers occur in people under 40 years of age with 81.1% of that 5% in the age-group of 30 to 39 and 18.9% in the age-group of 20 to 29.[90]

In 2014, stomach cancer resulted in 0.61% of deaths (13,303 cases) in the U.S.[91] In China, stomach cancer accounted for 3.56% of all deaths (324,439 cases).[92] The highest rate of stomach cancer was in Mongolia, at 28 cases per 100,000 people.[93]

In the United Kingdom, stomach cancer is the fifteenth most-common cancer (around 7,100 people were diagnosed with stomach cancer in 2011), and it is the tenth most-common cause of cancer-related deaths (around 4,800 people died in 2012).[94]

Incidence and mortality rates of gastric cancer vary greatly in Africa. The GLOBOCAN system is currently the most widely used method to compare these rates between countries, but African incidence and mortality rates are seen to differ among countries, possibly due to the lack of universal access to a registry system for all countries.[95] Variation as drastic as estimated rates from 0.3/100000 in Botswana to 20.3/100000 in Mali have been observed.[95] In Uganda, the incidence of gastric cancer has increased from the 1960s measurement of 0.8/100000 to 5.6/100000.[95] Gastric cancer, though present, is relatively low when compared to countries with high incidence like Japan and China. One suspected cause of the variation within Africa and between other countries is due to different strains of the Helicobacter pylori bacteria. The trend commonly-seen is that H. pylori infection increases the risk for gastric cancer. However, this is not the case in Africa, giving this phenomenon the name the “African enigma.”[96] Although this bacteria is found in Africa, evidence has supported that different strains with mutations in the bacterial genotype may contribute to the difference in cancer development between African countries and others outside the continent.[96] However, increasing access to health care and treatment measures have been commonly-associated with the rising incidence, particularly in Uganda.[95]

Other animals[edit | edit source]

The stomach is a muscular organ of the gastrointestinal tract that holds food and begins the digestive process by secreting gastric juice. The most common cancers of the stomach are adenocarcinomas but other histological types have been reported. Signs vary but may include vomiting (especially if blood is present), weight loss, anemia, and lack of appetite. Bowel movements may be dark and tarry in nature. In order to determine whether cancer is present in the stomach, special X-rays and/or abdominal ultrasound may be performed. Gastroscopy, a test using an instrument called endoscope to examine the stomach, is a useful diagnostic tool that can also take samples of the suspected mass for histopathological analysis to confirm or rule out cancer. The most definitive method of cancer diagnosis is through open surgical biopsy.[97] Most stomach tumors are malignant with evidence of spread to lymph nodes or liver, making treatment difficult. Except for lymphoma, surgery is the most frequent treatment option for stomach cancers but it is associated with significant risks.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 "Gastric Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)". NCI. 17 April 2014. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 5.4. ISBN 978-9283204299.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Chang AH, Parsonnet J (October 2010). "Role of bacteria in oncogenesis". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 23 (4): 837–57. doi:10.1128/CMR.00012-10. PMC 2952975. PMID 20930075.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 González CA, Sala N, Rokkas T (September 2013). "Gastric cancer: epidemiologic aspects". Helicobacter. 18 (Suppl 1): 34–8. doi:10.1111/hel.12082. PMID 24011243.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Stomach (Gastric) Cancer Prevention (PDQ®)". NCI. 27 February 2014. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 Orditura M, Galizia G, Sforza V, Gambardella V, Fabozzi A, Laterza MM, Andreozzi F, Ventriglia J, Savastano B, Mabilia A, Lieto E, Ciardiello F, De Vita F (February 2014). "Treatment of gastric cancer". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 20 (7): 1635–49. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i7.1635. PMC 3930964. PMID 24587643.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Cancer of the Stomach - Cancer Stat Facts". SEER. Archived from the original on 7 December 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "がん診療連携拠点病院等院内がん登録生存率集計:[国立がん研究センター がん登録・統計]". ganjoho.jp. Archived from the original on 16 September 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ↑ GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Bray, F; Ferlay, J; Soerjomataram, I; Siegel, RL; Torre, LA; Jemal, A (November 2018). "Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 68 (6): 394–424. doi:10.3322/caac.21492. PMID 30207593. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ↑ "Stomach (Gastric) Cancer". NCI. January 1980. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ↑ Ruddon, Raymond W. (2007). Cancer biology (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 223. ISBN 9780195175431. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015.

- ↑ Sim, edited by Fiona; McKee, Martin (2011). Issues in public health (2nd ed.). Maidenhead: Open University Press. p. 74. ISBN 9780335244225. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 Wagner AD, Syn NL, Moehler M, Grothe W, Yong WP, Tai BC, Ho J, Unverzagt S (August 2017). "Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8: CD004064. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004064.pub4. PMC 6483552. PMID 28850174.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Stathis, A; Bertoni, F; Zucca, E (September 2010). "Treatment of gastric marginal zone lymphoma of MALT type". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 11 (13): 2141–52. doi:10.1517/14656566.2010.497141. PMID 20586708.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Chapter 1.1". World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. ISBN 978-9283204299.

- ↑ Hochhauser, Jeffrey Tobias, Daniel (2010). Cancer and its management (6th ed.). Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 259. ISBN 9781444306378. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015.

- ↑ Khleif, Edited by Roland T. Skeel, Samir N. (2011). Handbook of cancer chemotherapy (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolter Kluwer. p. 127. ISBN 9781608317820. Archived from the original on 18 September 2015.

- ↑ Moore, edited by Rhonda J.; Spiegel, David (2004). Cancer, culture, and communication. New York: Kluwer Academic. p. 139. ISBN 9780306478857.

- ↑ "Statistics and outlook for stomach cancer". Cancer Research UK. Archived from the original on 5 January 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ↑ "Guidance on Commissioning Cancer Services Improving Outcomes in Upper Gastro-intestinal Cancers" (PDF). NHS. January 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2012.

- ↑ Lee YY, Derakhshan MH (June 2013). "Environmental and Lifestyle Risk Factors of Gastric Cancer" (PDF). Archives of Iranian Medicine. 16 (6): 358–65. PMID 23725070. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2020. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ↑ Chandanos E, Lagergren J (November 2008). "Oestrogen and the enigmatic male predominance of gastric cancer". European Journal of Cancer. 44 (16): 2397–403. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2008.07.031. PMID 18755583.

- ↑ Qin J, Liu M, Ding Q, Ji X, Hao Y, Wu X, Xiong J (October 2014). "The direct effect of estrogen on cell viability and apoptosis in human gastric cancer cells". Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 395 (1–2): 99–107. doi:10.1007/s11010-014-2115-2. PMID 24934239.

- ↑ "Proceedings of the fourth Global Vaccine Research Forum" (PDF). Initiative for Vaccine Research team of the Department of Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals. WHO. April 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 July 2009. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer…

- ↑ Hatakeyama M, Higashi H (December 2005). "Helicobacter pylori CagA: a new paradigm for bacterial carcinogenesis". Cancer Science. 96 (12): 835–43. doi:10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00130.x. PMID 16367902.

- ↑ "Developing a vaccine for the Epstein-Barr Virus could prevent up to 200,000 cancers globally say experts". Cancer Research UK. 24 March 2014. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "What Are The Risk Factors For Stomach Cancer(Website)". American Cancer Society. Archived from the original on 6 July 2010. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ↑ Nomura A, Grove JS, Stemmermann GN, Severson RK (November 1990). "Cigarette smoking and stomach cancer". Cancer Research. 50 (21): 7084. PMID 2208177. Archived from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- ↑ Trédaniel J, Boffetta P, Buiatti E, Saracci R, Hirsch A (August 1997). "Tobacco smoking and gastric cancer: review and meta-analysis". International Journal of Cancer. 72 (4): 565–73. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970807)72:4<565::AID-IJC3>3.0.CO;2-O. PMID 9259392.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 Thrumurthy SG, Chaudry MA, Hochhauser D, Mughal M (November 2013). "The diagnosis and management of gastric cancer". BMJ. 347 (16): f6367. doi:10.1136/bmj.f6367. PMID 24191271.

- ↑ Venturi S, Donati FM, Venturi A, Venturi M (August 2000). "Environmental iodine deficiency: A challenge to the evolution of terrestrial life?". Thyroid. 10 (8): 727–9. doi:10.1089/10507250050137851. PMID 11014322.

- ↑ Theodoratou E, Timofeeva M, Li X, Meng X, Ioannidis JP (August 2017). "Nature, Nurture, and Cancer Risks: Genetic and Nutritional Contributions to Cancer". Annual Review of Nutrition (Review). 37: 293–320. doi:10.1146/annurev-nutr-071715-051004. PMC 6143166. PMID 28826375.

- ↑ Jakszyn P, Gonzalez CA (July 2006). "Nitrosamine and related food intake and gastric and oesophageal cancer risk: a systematic review of the epidemiological evidence". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 12 (27): 4296–303. doi:10.3748/wjg.v12.i27.4296. PMC 4087738. PMID 16865769.

- ↑ Alonso-Amelot ME, Avendaño M (March 2002). "Human carcinogenesis and bracken fern: a review of the evidence". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 9 (6): 675–86. doi:10.2174/0929867023370743. PMID 11945131. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011.

- ↑ Buckland G, Agudo A, Luján L, Jakszyn P, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB, Palli D, Boeing H, Carneiro F, Krogh V, Sacerdote C, Tumino R, Panico S, Nesi G, Manjer J, Regnér S, Johansson I, Stenling R, Sanchez MJ, Dorronsoro M, Barricarte A, Navarro C, Quirós JR, Allen NE, Key TJ, Bingham S, Kaaks R, Overvad K, Jensen M, Olsen A, Tjønneland A, Peeters PH, Numans ME, Ocké MC, Clavel-Chapelon F, Morois S, Boutron-Ruault MC, Trichopoulou A, Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, Lund E, Couto E, Boffeta P, Jenab M, Riboli E, Romaguera D, Mouw T, González CA (February 2010). "Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and risk of gastric adenocarcinoma within the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort study". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 91 (2): 381–90. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.28209. PMID 20007304.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Crew KD, Neugut AI (January 2006). "Epidemiology of gastric cancer". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 12 (3): 354–62. doi:10.3748/wjg.v12.i3.354. PMC 4066052. PMID 16489633.

- ↑ Hampel H, Abraham NS, El-Serag HB (August 2005). "Meta-analysis: obesity and the risk for gastroesophageal reflux disease and its complications". Annals of Internal Medicine. 143 (3): 199–211. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-143-3-200508020-00006. PMID 16061918.

- ↑ Josefssson, M.; Ekblad, E. (2009). "22. Sodium Iodide Symporter (NIS) in Gastric Mucosa: Gastric Iodide Secretion". In Preedy, Victor R.; Burrow, Gerard N.; Watson, Ronald (eds.). Comprehensive Handbook of Iodine: Nutritional, Biochemical, Pathological and Therapeutic Aspects. Elsevier. pp. 215–220. ISBN 978-0-12-374135-6.

- ↑ Venturi, Sebastiano (2011). "Evolutionary Significance of Iodine". Current Chemical Biology. 5 (3): 155–162. doi:10.2174/187231311796765012. ISSN 1872-3136.

- ↑ Venturi S, Donati FM, Venturi A, Venturi M, Grossi L, Guidi A (January 2000). "Role of iodine in evolution and carcinogenesis of thyroid, breast and stomach". Advances in Clinical Pathology. 4 (1): 11–7. PMID 10936894. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 42.4 "Hereditary Diffuse Cancer". No Stomach for Cancer. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ↑ "Gastric Cancer — Adenocarcinoma". International Cancer Genome Consortium. Archived from the original on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ↑ "Gastric Cancer — Intestinal- and diffuse-type". International Cancer Genome Consortium. Archived from the original on 7 February 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ↑ Brooks-Wilson AR, Kaurah P, Suriano G, Leach S, Senz J, Grehan N, Butterfield YS, Jeyes J, Schinas J, Bacani J, Kelsey M, Ferreira P, MacGillivray B, MacLeod P, Micek M, Ford J, Foulkes W, Australie K, Greenberg C, LaPointe M, Gilpin C, Nikkel S, Gilchrist D, Hughes R, Jackson CE, Monaghan KG, Oliveira MJ, Seruca R, Gallinger S, Caldas C, Huntsman D (July 2004). "Germline E-cadherin mutations in hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: assessment of 42 new families and review of genetic screening criteria". Journal of Medical Genetics. 41 (7): 508–17. doi:10.1136/jmg.2004.018275. PMC 1735838. PMID 15235021.

- ↑ Tseng CH, Tseng FH (February 2014). "Diabetes and gastric cancer: the potential links". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 20 (7): 1701–11. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i7.1701. PMC 3930970. PMID 24587649.

- ↑ Crosby DA, Donohoe CL, Fitzgerald L, Muldoon C, Hayes B, O'Toole D, Reynolds JV (2004). "Gastric neuroendocrine tumours". Digestive Surgery. 29 (4): 331–48. doi:10.1159/000342988. PMID 23075625.

- ↑ Kim J, Cheong JH, Chen J, Hyung WJ, Choi SH, Noh SH (June 2004). "Menetrier's disease in korea: report of two cases and review of cases in a gastric cancer prevalent region" (PDF). Yonsei Medical Journal. 45 (3): 555–60. doi:10.3349/ymj.2004.45.3.555. PMID 15227748. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ↑ Tsukamoto T, Mizoshita T, Tatematsu M (2006). "Gastric-and-intestinal mixed-type intestinal metaplasia: aberrant expression of transcription factors and stem cell intestinalization". Gastric Cancer. 9 (3): 156–66. doi:10.1007/s10120-006-0375-6. PMID 16952033.

- ↑ Virmani V, Khandelwal A, Sethi V, Fraser-Hill M, Fasih N, Kielar A (August 2012). "Neoplastic stomach lesions and their mimickers: spectrum of imaging manifestations". Cancer Imaging. 12: 269–78. doi:10.1102/1470-7330.2012.0031. PMC 3458788. PMID 22935192.

- ↑ Xu ZQ, Broza YY, Ionsecu R, Tisch U, Ding L, Liu H, Song Q, Pan YY, Xiong FX, Gu KS, Sun GP, Chen ZD, Leja M, Haick H (March 2013). "A nanomaterial-based breath test for distinguishing gastric cancer from benign gastric conditions". British Journal of Cancer. 108 (4): 941–50. doi:10.1038/bjc.2013.44. PMC 3590679. PMID 23462808. Lay summary.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|lay-url=(help); Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help) - ↑ Amal H, Leja M, Funka K, Skapars R, Sivins A, Ancans G, Liepniece-Karele I, Kikuste I, Lasina I, Haick H (March 2016). "Detection of precancerous gastric lesions and gastric cancer through exhaled breath". Gut. 65 (3): 400–7. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308536. PMID 25869737.

- ↑ Inoue H, Kudo SE, Shiokawa A (January 2005). "Technology insight: Laser-scanning confocal microscopy and endocytoscopy for cellular observation of the gastrointestinal tract". Nature Clinical Practice. Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2 (1): 31–7. doi:10.1038/ncpgasthep0072. PMID 16265098.

- ↑ Pentenero M, Carrozzo M, Pagano M, Gandolfo S (July 2004). "Oral acanthosis nigricans, tripe palms and sign of leser-trélat in a patient with gastric adenocarcinoma". International Journal of Dermatology. 43 (7): 530–2. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02159.x. PMID 15230897.

- ↑ Kumar; et al. (2010). Pathologic Basis of Disease (8th ed.). Saunders Elsevier. p. 784. ISBN 978-1-4160-3121-5.

- ↑ Kumar 2010, p. 786

- ↑ Burkitt MD, Duckworth CA, Williams JM, Pritchard DM (February 2017). "Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric pathology: insights from in vivo and ex vivo models". Disease Models & Mechanisms. 10 (2): 89–104. doi:10.1242/dmm.027649. PMC 5312008. PMID 28151409.

- ↑ Qu Q, Xuan W, Fan GH (January 2015). "Roles of resolvins in the resolution of acute inflammation". Cell Biology International. 39 (1): 3–22. doi:10.1002/cbin.10345. PMID 25052386.

- ↑ Lim JS, Yun MJ, Kim MJ, Hyung WJ, Park MS, Choi JY, Kim TS, Lee JD, Noh SH, Kim KW (2006). "CT and PET in stomach cancer: preoperative staging and monitoring of response to therapy". Radiographics. 26 (1): 143–56. doi:10.1148/rg.261055078. PMID 16418249.

- ↑ "Detailed Guide: Stomach Cancer Treatment Choices by Type and Stage of Stomach Cancer". American Cancer Society. 3 November 2009. Archived from the original on 8 October 2009.

- ↑ Guy Slowik (October 2009). "What Are The Stages Of Stomach Cancer?". ehealthmd.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2010.

- ↑ "Detailed Guide: Stomach Cancer: How Is Stomach Cancer Staged?". American Cancer Society. Archived from the original on 25 March 2008.

- ↑ Paterson HM, McCole D, Auld CD (May 2006). "Impact of open-access endoscopy on detection of early oesophageal and gastric cancer 1994 – 2003: population-based study". Endoscopy. 38 (5): 503–7. doi:10.1055/s-2006-925124. PMID 16767587.

- ↑ Crane SJ, Locke GR, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Romero Y, Talley NJ (October 2008). "Survival trends in patients with gastric and esophageal adenocarcinomas: a population-based study". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 83 (10): 1087–94. doi:10.4065/83.10.1087. PMC 2597541. PMID 18828967.

- ↑ Heise K, Bertran E, Andia ME, Ferreccio C (April 2009). "Incidence and survival of stomach cancer in a high-risk population of Chile". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 15 (15): 1854–62. doi:10.3748/wjg.15.1854. PMC 2670413. PMID 19370783.

- ↑ Ford AC, Forman D, Hunt RH, Yuan Y, Moayyedi P (May 2014). "Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy to prevent gastric cancer in healthy asymptomatic infected individuals: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". BMJ. 348: g3174. doi:10.1136/bmj.g3174. PMC 4027797. PMID 24846275.

- ↑ Woo HD, Park S, Oh K, Kim HJ, Shin HR, Moon HK, Kim J (2014). "Diet and cancer risk in the Korean population: a meta- analysis" (PDF). Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 15 (19): 8509–19. doi:10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.19.8509. PMID 25339056. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 June 2015.

- ↑ Kong P, Cai Q, Geng Q, Wang J, Lan Y, Zhan Y, Xu D (2014). "Vitamin intake reduce the risk of gastric cancer: meta-analysis and systematic review of randomized and observational studies". PLOS One. 9 (12): e116060. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k6060K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0116060. PMC 4280145. PMID 25549091.

- ↑ Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Simonetti RG, Gluud C (July 2008). "Antioxidant supplements for preventing gastrointestinal cancers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD004183. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004183.pub3. PMID 18677777.

- ↑ Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud LL, Simonetti RG, Gluud C (March 2012). "Antioxidant supplements for prevention of mortality in healthy participants and patients with various diseases". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Submitted manuscript). 3 (3): CD007176. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007176.pub2. hdl:10138/136201. PMID 22419320. Archived from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ↑ Kumar, Vivek; Soni, Parita; Garg, Mohit; Kamholz, Stephan; Chandra, Abhinav B. (13 September 2018). "Emerging Therapies in the Management of Advanced-Stage Gastric Cancer". Frontiers in Pharmacology. Frontiers Media SA. 9. doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.00404. ISSN 1663-9812.

- ↑ Wadhwa R, Taketa T, Sudo K, Blum MA, Ajani JA (June 2013). "Modern oncological approaches to gastric adenocarcinoma". Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 42 (2): 359–69. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2013.01.011. PMID 23639645.

- ↑ Chen K, Xu XW, Zhang RC, Pan Y, Wu D, Mou YP (August 2013). "Systematic review and meta-analysis of laparoscopy-assisted and open total gastrectomy for gastric cancer". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 19 (32): 5365–76. doi:10.3748/wjg.v19.i32.5365. PMC 3752573. PMID 23983442.

- ↑ Pretz JL, Wo JY, Mamon HJ, Kachnic LA, Hong TS (July 2013). "Chemoradiation therapy: localized esophageal, gastric, and pancreatic cancer". Surgical Oncology Clinics of North America. 22 (3): 511–24. doi:10.1016/j.soc.2013.02.005. PMID 23622077.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Meza-Junco J, Au HJ, Sawyer MB (March 2011). "Critical appraisal of trastuzumab in treatment of advanced stomach cancer". Cancer Management and Research. 3: 57–64. doi:10.2147/CMAR.S12698. PMC 3085240. PMID 21556317.

- ↑ Best LM, Mughal M, Gurusamy KS (March 2016). "Laparoscopic versus open gastrectomy for gastric cancer" (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3: CD011389. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011389.pub2. PMC 6769173. PMID 27030300. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 July 2018. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Syn NL, Wee I, Shabbir A, Kim G, So JB (December 2018). "Pouch Versus No Pouch Following Total gastrectomy: Meta-analysis of Randomized and Non-randomized Studies". Annals of Surgery. Publish Ahead of Print: 1041–1053. doi:10.1097/sla.0000000000003082. PMID 30571657.

- ↑ Sun J, Song Y, Wang Z, Chen X, Gao P, Xu Y, Zhou B, Xu H (December 2013). "Clinical significance of palliative gastrectomy on the survival of patients with incurable advanced gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis" (PDF). BMC Cancer. 13 (1): 577. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-13-577. PMC 4235220. PMID 24304886. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 April 2014.

- ↑ Scartozzi M, Galizia E, Verdecchia L, Berardi R, Antognoli S, Chiorrini S, Cascinu S (April 2007). "Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer: across the years for a standard of care". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 8 (6): 797–808. doi:10.1517/14656566.8.6.797. PMID 17425475.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Fusco N, Rocco EG, Del Conte C, Pellegrini C, Bulfamante G, Di Nuovo F, Romagnoli S, Bosari S (June 2013). "HER2 in gastric cancer: a digital image analysis in pre-neoplastic, primary and metastatic lesions". Modern Pathology. 26 (6): 816–24. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2012.228. PMID 23348899.

- ↑ Cabebe, EC; Mehta, VK; Fisher, G, Jr (21 January 2014). Talavera, F; Movsas, M; McKenna, R; Harris, JE (eds.). "Gastric Cancer". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "The stomach cancer proteome – The Human Protein Atlas". www.proteinatlas.org. Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2017.

- ↑ Uhlen M, Zhang C, Lee S, Sjöstedt E, Fagerberg L, Bidkhori G, Benfeitas R, Arif M, Liu Z, Edfors F, Sanli K, von Feilitzen K, Oksvold P, Lundberg E, Hober S, Nilsson P, Mattsson J, Schwenk JM, Brunnström H, Glimelius B, Sjöblom T, Edqvist PH, Djureinovic D, Micke P, Lindskog C, Mardinoglu A, Ponten F (August 2017). "A pathology atlas of the human cancer transcriptome". Science. 357 (6352): eaan2507. doi:10.1126/science.aan2507. PMID 28818916.

- ↑ Calik I, Calik M, Sarikaya B, Ozercan IH, Arslan R, Artas G, Dagli AF. P2X7R as an independent prognostic indicator in gastric cancer. Bosn J of Basic Med Sci [Internet]. 2020Feb.19 [cited 2020Mar.14];. Available from: https://www.bjbms.org/ojs/index.php/bjbms/article/view/4620 Archived 3 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P (2005). "Global cancer statistics, 2002". Ca. 55 (2): 74–108. doi:10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. PMID 15761078.

- ↑ "Are the number of cancer cases increasing or decreasing in the world?". WHO Online Q&A. WHO. 1 April 2008. Archived from the original on 14 May 2009. Retrieved 11 May 2009.

- ↑ World Cancer Report 2014. International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization. 2014. ISBN 978-92-832-0432-9.

- ↑ Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. (December 2012). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30050819. PMID 23245604. Archived from the original on 19 May 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ↑ "PRESS RELEASE N° 224 Global battle against cancer won't be won with treatment alone: Effective prevention measures urgently needed to prevent cancer crisis" (PDF). World Health Organization. 3 February 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ↑ "Gastric Cancer in Young Adults". Revista Brasileira de Cancerologia. 46 (3). July 2000. Archived from the original on 3 July 2009.

- ↑ "Health profile: United States". Le Duc Media. Archived from the original on 14 January 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ↑ "Health profile: China". Le Duc Media. Archived from the original on 3 January 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ↑ "Stomach Cancer: Death Rate Per 100,000". Le Duc Media. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ↑ "Stomach cancer statistics". Cancer Research UK. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 95.2 95.3 Asombang AW, Rahman R, Ibdah JA (April 2014). "Gastric cancer in Africa: current management and outcomes". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 20 (14): 3875–9. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i14.3875. PMC 3983443. PMID 24833842.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 Louw JA, Kidd MS, Kummer AF, Taylor K, Kotze U, Hanslo D (December 2001). "The relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection, the virulence genotypes of the infecting strain and gastric cancer in the African setting". Helicobacter. 6 (4): 268–73. doi:10.1046/j.1523-5378.2001.00044.x. PMID 11843958.

- ↑ Withrow SJ, MacEwen EG, eds. (2001). Small Animal Clinical Oncology (3rd ed.). W.B. Saunders.

External links[edit | edit source]

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- National Cancer Institute Gastric cancer treatment guidelines Archived 27 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine

Categories: [Stomach cancer] [Abdomen] [Epstein–Barr virus-associated diseases] [Infectious causes of cancer] [RTT]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 05/14/2024 04:33:54 | 1 views

☰ Source: https://mdwiki.org/wiki/Stomach_cancer | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

_H&E_magn_400x.jpg)

.jpg)

KSF

KSF