Federalist Papers

From Nwe

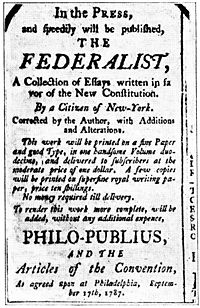

From Nwe The Federalist Papers are a series of 85 articles arguing for the ratification of the United States Constitution. They were first published serially from October 1787 to August 1788 in New York City newspapers. A compilation, called The Federalist, was published in 1788. The Federalist Papers serve as a primary source for interpretation of the Constitution, as they outline the philosophy and motivation of the proposed system of government. The authors of the Federalist Papers also used the opportunity to interpret certain provisions of the constitution to (i) influence the vote on ratification and (ii) influence future interpretations of the provisions in question.

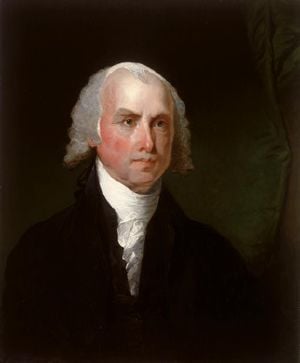

The articles were written by James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and John Jay, under the pseudonym "Publius," in honor of Roman consul Publius Valerius Publicola.[1] Madison is generally credited as the father of the Constitution and became the fourth President of the United States. Hamilton was an influential delegate at the Constitutional Convention, and later the first Secretary of the Treasury. John Jay would become the first Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. Hamilton penned the majority of the papers, and Madison made several significant contributions to the series. Jay, who fell ill early in the project, wrote only five.

Federalist No. 10 and Federalist No. 51 are generally regarded as the most influential of the 85 articles; no. 10 advocates for a large, strong republic and includes discussion on the dangers of factions, no. 51 explains the need for the separation of powers. Federalist No. 84 is also notable for its opposition to what later became the United States Bill of Rights. The whole series is cited by scholars and jurists as an authoritative interpretation and explication of the meaning of the Constitution.

Origins

The Constitution was sent to the states for ratification in late September 1787. Immediately, it was the target of a substantial number of articles and public letters written by Anti-Federalists and other opponents of the Constitution. For instance, the important Anti-Federalist authors "Cato" and "Brutus" debuted in New York papers on September 27 and October 18, respectively. Hamilton began the Federalist Papers project as a response to the opponents of ratification, a response that would explain the new Constitution to the residents of New York and persuade them to ratify it. He wrote in Federalist No. 1 that the series would "endeavor to give a satisfactory answer to all the objections which shall have made their appearance, that may seem to have any claim to your attention."

Hamilton recruited collaborators for the project. He enlisted Jay, who fell ill and was unable to contribute much to the series. Madison, in New York as a delegate to the Congress, was recruited by Hamilton and Jay, and became Hamilton's major collaborator. Gouverneur Morris and William Duer were also apparently considered; Morris turned down the invitation and Hamilton rejected three essays written by Duer.[2] Duer later wrote in support of the three Federalist authors under the name "Philo-Publius," or "Friend of Publius."

Hamilton also chose "Publius" as the pseudonym under which the series would be written. While many other pieces representing both sides of the constitutional debate were written under Roman names, Albert Furtwangler contends that "'Publius' was a cut above 'Caesar' or 'Brutus' or even 'Cato.' Publius Valerius was not a late defender of the republic but one of its founders. His more famous name, Publicola, meant 'friend of the people.'"[3] It was not the first time Hamilton had used this pseudonym: in 1778, he had applied it to three letters attacking Samuel Chase.

Publication

The Federalist Papers initially appeared in three New York newspapers: the Independent Journal, the New-York Packet and the Daily Advertiser, beginning on October 27, 1787. Between them, Hamilton, Madison and Jay kept up a rapid pace, with at times three or four new essays by Publius appearing in the papers in a week. Hamilton also encouraged the reprinting of the essay in newspapers outside New York State, and indeed they were published in a number of other states where the ratification debate was taking place.

The high demand for the essays led to their publication in a more permanent form. On January 1, 1788, the New York publishing firm J. & A. McLean announced that they would publish the first thirty-six essays as a bound volume; that volume was released on March 2 and was titled The Federalist. New essays continued to appear in the newspapers; Federalist No. 77 was the last number to first appear in that form, on April 2. A second bound volume containing the last forty-nine essays were released on May 28. The remaining eight papers were later published in the newspapers as well.[4]

A number of later publications are worth noting. A 1792 French edition ended the collective anonymity of Publius, announcing that the work had been written by "MM Hamilton, Maddisson E Gay," citizens of the State of New York. In 1802 George Hopkins published an American edition that similarly named the authors. Hopkins wished as well that "the name of the writer should be prefixed to each number," but at this point Hamilton insisted that this was not to be, and the division of the essays between the three authors remained a secret.[5]

The first publication to divide the papers in such a way was an 1810 edition that used a list provided by Hamilton to associate the authors with their numbers; this edition appeared as two volumes of the compiled Works of Hamilton. In 1818, Jacob Gideon published a new edition with a new listing of authors, based on a list provided by Madison. The difference between Hamilton's list and Madison's form the basis for a dispute over the authorship of a dozen of the essays.[6]

The disputed essays

The authorship of 73 of the Federalist essays is fairly certain. Twelve are disputed, though some newer evidence suggests Madison as the author. The first open designation of which essay belonged to whom was provided by Hamilton, who in the days before his ultimately fatal duel with Aaron Burr provided his lawyer with a list detailing the author of each number. This list credited Hamilton with a full 63 of the essays (three of those being jointly written with Madison), almost three quarters of the whole, and was used as the basis for an 1810 printing that was the first to make specific attribution for the essays.

Madison did not immediately dispute Hamilton's list, but provided his own list for the 1818 Gideon edition of The Federalist. Madison claimed 29 numbers for himself, and he suggested that the difference between the two lists was "owing doubtless to the hurry in which [Hamilton's] memorandum was made out." A known error in Hamilton's list—Hamilton incorrectly ascribed Federalist No. 54 to Jay, when in fact Jay wrote Federalist No. 64—has provided some evidence for Madison's suggestion.[7]

Statistical analysis has been undertaken a number of times to try to decide based on word frequencies and writing styles, and nearly all of the statistical studies show that all 12 disputed papers were written by Madison.[8][9]

List of articles

This is a listing of the Federalist papers.

| 1 | General Introduction |

| 2-7 | Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence |

| 8 | The Consequences of Hostilities Between the States |

| 9-10 | The Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection |

| 11 | The Utility of the Union in Respect to Commercial Relations and a Navy |

| 12 | The Utility of the Union in Respect to Revenue |

| 13 | Advantage of the Union in Respect to Economy in Government |

| 14 | Objections to the Proposed Constitution from Extent of Territory Answered |

| 15-20 | The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union |

| 21-22 | Other Defects of the Present Confederation |

| 23 | The Necessity of a Government as Energetic as the One Proposed to the Preservation of the Union |

| 24-25 | The Powers Necessary to the Common Defense Further Considered |

| 26-28 | The Idea of Restraining the Legislative Authority in Regard to the Common Defense Considered |

| 29 | Concerning the Militia |

| 30-36 | Concerning the General Power of Taxation |

| 37 | Concerning the Difficulties of the Convention in Devising a Proper Form of Government |

| 38 | The Same Subject Continued, and the Incoherence of the Objections to the New Plan Exposed |

| 39 | The Conformity of the Plan to Republican Principles |

| 40 | The Powers of the Convention to Form a Mixed Government Examined and Sustained |

| 41-43 | General View of the Powers Conferred by the Constitution |

| 44 | Restrictions on the Authority of the Several States |

| 45 | The Alleged Danger From the Powers of the Union to the State Governments Considered |

| 46 | The Influence of the State and Federal Governments Compared |

| 47 | The Particular Structure of the New Government and the Distribution of Power Among Its Different Parts |

| 48 | These Departments Should Not Be So Far Separated as to Have No Constitutional Control Over Each Other |

| 49 | Method of Guarding Against the Encroachments of Any One Department of Government by Appealing to the People Through a Convention |

| 50 | Periodic Appeals to the People Considered |

| 51 | The Structure of the Government Must Furnish the Proper Checks and Balances Between the Different Departments |

| 52-53 | The House of Representatives |

| 54 | The Apportionment of Members Among the States |

| 55-56 | The Total Number of the House of Representatives |

| 57 | The Alleged Tendency of the Plan to Elevate the Few at the Expense of the Many Considered in Connection with Representation |

| 58 | Objection that the Number of Members Will Not Be Augmented as the Progress of Population Demands Considered |

| 59-61 | Concerning the Power of Congress to Regulate the Election of Members |

| 62-63 | The Senate |

| 64-65 | The Powers of the Senate |

| 66 | Objections to the Power of the Senate To Set as a Court for Impeachments Further Considered |

| 67-77 | The Executive Department |

| 78-83 | The Judiciary Department |

| 84 | Certain General and Miscellaneous Objections to the Constitution Considered and Answered |

| 85 | Concluding Remarks |

Judicial use and interpretation

Federal judges frequently use the Federalist Papers when interpreting the Constitution as a contemporary account of the intentions of the framers and ratifiers. However, the amount of deference that should be given to the Federalist Papers in constitutional interpretation has always been somewhat controversial. As early as 1819, Chief Justice John Marshall said about the Federalist Papers in the famous case McCulloch v. Maryland that "the opinions expressed by the authors of that work have been justly supposed to be entitled to great respect in expounding the Constitution. No tribute can be paid to them which exceeds their merit; but in applying their opinions to the cases which may arise in the progress of our government, a right to judge of their correctness must be retained."

Opposition to the Bill of Rights

The Federalist Papers (specifically Federalist No. 84) are remarkable for their opposition to what later became the United States Bill of Rights. The idea of adding a bill of rights to the constitution was originally controversial because the constitution, as written, did not specifically enumerate or protect the rights of the people. Alexander Hamilton, in Federalist No. 84, feared that such an enumeration, once written down explicitly, would later be interpreted as a list of the only rights that people had.

However, Hamilton's opposition to the Bill of Rights was far from universal. Robert Yates, writing under the pseudonym Brutus, articulated a contrary viewpoint in the so-called Anti-Federalist No. 84, asserting that a government unrestrained by such a bill could easily devolve into tyranny. Other supporters of the Bill argued that a list of rights would not and should not be interpreted as exhaustive; i.e., that these rights were examples of important rights that people had, but that people had other rights as well. People of this school of thought were confident that the judiciary would interpret these rights in an expansive fashion.

Federalist No. 10

The essay is the most famous of the Federalist Papers, along with the Federalist No. 51, also by James Madison, and is among the most highly regarded of all American political writings.[10]

No. 10 addresses the question of how to guard against "factions," groups of citizens with interests contrary to the rights of others or the interests of the whole community. In today's discourse the term "special interest" often carries the same connotation. Madison argued that a strong, large republic would be a better guard against those dangers than smaller republics—for instance, the individual states. Opponents of the Constitution offered counterarguments to his position, which were substantially derived from the commentary of Montesquieu on this subject.

Federalist No. 10 continues a theme begun in Federalist No. 9; it is titled, "The Same Subject Continued: The Union as a Safeguard Against Domestic Faction and Insurrection." Jurists have frequently read No. 10 to mean that the Founding Fathers did not intend the United States government to be partisan.

The question of faction

Federalist No. 10 continues the discussion of a question broached in Hamilton's Federalist No. 9. Hamilton had addressed the destructive role of faction in breaking apart a republic. The question Madison answers, then, is how to eliminate the negative effects of faction. He defines a faction as "a number of citizens, whether amounting to a minority or majority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent and aggregate interests of the community." He saw direct democracy as a danger to individual rights and advocated a representative democracy (also called a republic), in order to protect individual liberty from majority rule. He says, "A pure democracy can admit no cure for the mischiefs of faction. A common passion or interest will be felt by a majority, and there is nothing to check the inducements to sacrifice the weaker party. Hence it is, that democracies have ever been found incompatible with personal security or the rights of property; and have, in general, been as short in their lives as they have been violent in their deaths."

Like the anti-Federalists who opposed him, Madison was substantially influenced by the work of Montesquieu, though Madison and Montesquieu disagreed on the question addressed in this essay. He also relied heavily on the philosophers of the Scottish Enlightenment, especially David Hume, whose influence is most clear in Madison's discussion of the types of faction.

Publius' argument

Madison takes the position that there are two ways to limit the damage caused by faction: removing the causes of faction or controlling its effects. He contends that there are two ways to remove the causes that provoke the development of factions. One, the elimination of liberty, he rejects as unacceptable. The other, creating a society homogeneous in opinion and interest, he sees as impractical because the causes of faction, among them variant economic interests, are inherent in a free society. Madison concludes that the damage caused by faction can be limited only by controlling its effects.

Madison notes that the principle of popular sovereignty should prevent minority factions from gaining power. Majority factions are then the problem, and he offers two ways to check them: prevent the "existence of the same passion or interest in a majority at the same time," or alternately render a majority faction unable to act. From this point Madison concludes that a small democracy cannot avoid majority faction, because small size means that common passions are likely to form among a majority of the people, and democracy means that the majority can enforce its will.

A republic, Madison writes, differs from a democracy in that its government is delegated to representatives, and as a result of this, it can be extended over a larger area. Regarding the first difference, Madison contends that a large republic will elect better delegates than a small one. In a large republic, the number of citizens per representative will be greater, and each chosen representative will be the best from a larger sample of people, resulting in better government. Also, the fact that each representative is chosen from a larger constituency means that "vicious arts" of electioneering will be less effective.

The fact that a republic can encompass larger areas and populations is a strength of that form of government. Madison believes that larger societies will have a greater variety of diverse parties and interest groups, which in competition will be less likely to yield a majority faction. This is a general application of the checks and balances principle, which is central to the American constitutional system. In conclusion, Madison emphasizes that the greater size of the Union will allow for more effective governments than were the states to remain more independent.

Though Madison argued for a large and diverse republic, the writers of the Federalist Papers recognized the need for a balance. They wanted a republic diverse enough to prevent faction but with enough commonality to maintain cohesion. In Federalist No. 2, John Jay counted as a blessing that America possessed "one united people—a people descended from the same ancestors, speaking the same language, professing the same religion." Madison himself addresses a limitation of his conclusion that large constituencies will provide better representatives. He notes that if constituencies are too large, the representatives will be "too little acquainted with all their local circumstances and lesser interests." He says that this problem is partly solved by federalism. No matter how large the constituencies of federal representatives, local matters will be looked after by state and local officials with naturally smaller constituencies.

Contemporary counterarguments: the Anti-Federalists

The Anti-Federalists vigorously contested the notion that a republic of diverse interests could survive. The author Cato (another pseudonym, most likely that of George Clinton) summarized the Anti-Federalist position in the article Cato no. 3:

Whoever seriously considers the immense extent of territory comprehended within the limits of the United States, together with the variety of its climates, productions, and commerce, the difference of extent, and number of inhabitants in all; the dissimilitude of interest, morals, and policies, in almost every one, will receive it as an intuitive truth, that a consolidated republican form of government therein, can never form a perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to you and your posterity, for to these objects it must be directed: this unkindred legislature therefore, composed of interests opposite and dissimilar in their nature, will in its exercise, emphatically be, like a house divided against itself.[11]

Generally, it was their position that republics about the size of the individual states could survive, but that a republic on the size of the Union would fail. A particular point in support of this was that most of the states were focused on one industry—to generalize, commerce and shipping in the northern states and plantation farming in the southern. The Anti-Federalist belief that the wide disparity in the economic interests of the various states would lead to controversy was perhaps realized in the American Civil War, which some scholars attribute to this disparity.[12] Madison himself, in a letter to Thomas Jefferson, noted that differing economic interests had created dispute, even when the Constitution was being written.[13]

The discussion of the ideal size for the republic was not limited to the options of individual states or encompassing union. In a letter to Richard Price, Benjamin Rush noted that "Some of our enlightened men who begin to despair of a more complete union of the States in Congress have secretly proposed an Eastern, Middle, and Southern Confederacy, to be united by an alliance offensive and defensive."[14] However, compromise ideas like this gained little traction.

In making their arguments, the Anti-Federalists appealed to both historical and theoretic evidence. On the theoretical side, they leaned heavily on the work of Montesquieu. The Anti-Federalists Brutus and Cato both quoted Montesquieu on the issue of the ideal size of a republic, citing his statement in The Spirit of the Laws that:

It is natural to a republic to have only a small territory, otherwise it cannot long subsist. In a large republic there are men of large fortunes, and consequently of less moderation; there are trusts too great to be placed in any single subject; he has interest of his own; he soon begins to think that he may be happy, great and glorious, by oppressing his fellow citizens; and that he may raise himself to grandeur on the ruins of his country. In a large republic, the public good is sacrificed to a thousand views; it is subordinate to exceptions, and depends on accidents. In a small one, the interest of the public is easier perceived, better understood, and more within the reach of every citizen; abuses are of less extent, and of course are less protected.

Brutus points out that the Greek and Roman states envisioned by many Americans as model republics (as evidenced by the choice of many authors on both sides of the debate to take Roman monikers) were small. Brutus also points out that the expansion of these republics resulted in a transition from free government to tyranny.[15]

Modern analysis and reaction

In the first century of the American republic, No. 10 was not regarded as among the more important numbers of The Federalist. For instance, in Democracy in America Alexis de Tocqueville refers specifically to more than 50 of the essays, but No. 10 is not among them.[16] Today, however, No. 10 is regarded as a seminal work of American democracy. In "The People's Vote," a popular survey conducted by the National Archives and Records Administration, National History Day, and U.S. News and World Report, No. 10 (along with Federalist No. 51, also by Madison) was chosen as the twentieth most influential document in United States history.[17]

Garry Wills is a noted critic of Madison's argument in Federalist No. 10. In his book Explaining America, he adopts the position of Robert Dahl in arguing that Madison's framework does not necessarily enhance the protections of minorities or ensure the common good. Instead, Wills claims: "Minorities can make use of dispersed and staggered governmental machinery to clog, delay, slow down, hamper, and obstruct the majority. But these weapons for delay are given to the minority irrespective of its factious or nonfactious character; and they can be used against the majority irrespective of its factious or nonfactious character. What Madison prevents is not faction, but action. What he protects is not the common good but delay as such."[18]

Application

Federalist No. 10 is the classic citation for the belief that the Founding Fathers and the constitutional framers did not intend American politics to be partisan. For instance, United States Supreme Court justice John Paul Stevens cites the paper for the statement, "Parties ranked high on the list of evils that the Constitution was designed to check."[19] Discussing a California provision that forbids candidates from running as independents within one year of holding a partisan affiliation, Justice Byron White made apparent the Court's belief that Madison spoke for the framers of the Constitution: "California apparently believes with the Founding Fathers that splintered parties and unrestrained factionalism may do significant damage to the fabric of government. See The Federalist, No. 10 (Madison)."[20]

Madison's argument that restraining liberty to limit faction is an unacceptable solution has been used by opponents of campaign finance limits. Justice Clarence Thomas, for example, invoked Federalist No. 10 in a dissent against a ruling supporting limits on campaign contributions, writing: "The Framers preferred a political system that harnessed such faction for good, preserving liberty while also ensuring good government. Rather than adopting the repressive 'cure' for faction that the majority today endorses, the Framers armed individual citizens with a remedy."[21]. It has also been used by those that seek fairer and equitable ballot access law, such as Richard Winger of Ballot Access News.

Notes

- ↑ Albert Furtwangler. The Authority of Publius: A Reading of the Federalist Papers. (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1984), 51.

- ↑ Furtwangler, 51-56.

- ↑ Furtwangler, 51.

- ↑ The Federalist timeline at [1] Study notes sparknotes.com. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- ↑ Douglass Adair. Fame and the Founding Fathers. (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1974), 40-41.

- ↑ Adair, 44-46.

- ↑ Adair, 48.

- ↑ Frederick Mosteller and David L. Wallace. Inference and Disputed Authorship: The Federalist. (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1964).

- ↑ Glenn Fung, "The disputed federalist papers: SVM feature selection via concave minimization." Journal of the ACM monograph online (New York City: ACM Press, 2003) The Disputed Federalist Papers. Retrieved May 27, 2007.

- ↑ David F. Epstein. The Political Theory of The Federalist. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984)

- ↑ Cato No. 3

- ↑ Roger L. Ransom. "Economics of the Civil War", August 25, 2001. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- ↑ [2].October 24, 1787 letter of Madison to Jefferson, at The Founders' Constitution web edition. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- ↑ Founders Documents.[3]. Benjamin Rush to Richard Price, 27 Oct. 1786. University of Chicago. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- ↑ Brutus No. 1

- ↑ Adair, 110

- ↑ "The People's Vote" at www.ourdocuments.govOurdocuments.gov. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ↑ Garry Wills. Explaining America. (New York: Penguin Books, 1982), 195.

- ↑ California Democratic Party v. Jones, 530 U.S. 567, 592 (2000) [4].findlaw.com.Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ↑ Storer v. Brown, 415 U.S. 724, 736 (1974) [5]. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ↑ Nixon v. Shrink Missouri Government PAC, 528 U.S. 377, 424 (2000) [6].Retrieved June 8, 2008.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adair, Douglass. Fame and the Founding Fathers. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1974. A collection of essays; that used here is "The Tenth Federalist Revisited."

- Epstein, David F. The Political Theory of The Federalist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

- Fung, Glenn. "The disputed federalist papers: SVM feature selection via concave minimization." Journal of the ACM monograph online (New York City: ACM Press, 2003) The Disputed Federalist Papers. Retrieved July 16, 2022.

- Furtwangler, Albert. The Authority of Publius: A Reading of the Federalist Papers. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1984.

- Hamilton, Alexander; Madison, James; and Jay, John. The Federalist. Edited by Jacob E. Cooke. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1961.

- Mosteller, Frederick and Wallace, David L., Inference and Disputed Authorship: The Federalist. Addison-Wesley, Reading, Mass., 1964.

- Storing, Herbert J., ed. The Complete Anti-Federalist. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981. A 7-volume edition containing most all relevant Anti-Federalist writings.

- Wills, Garry. Explaining America. New York: Penguin Books, 1982.

- Storer v. Brown, 415 U.S. 724 (1974). Findlaw. Retrieved July 16, 2022.

- Nixon v. Shrink Missouri Government PAC, 528 U.S. 377 (2000). Findlaw. Retrieved July 16, 2022.

- California Democratic Party v. Jones, 530 U.S. 567 (2000). Findlaw. Retrieved July 16, 2022.

Further reading

- Dietze, Gottfried. The Federalist: A Classic on Federalism and Free Government, Westport, Conn. : Greenwood Press, 1977. ISBN 9780837194660

- Epstein, David F. The Political Theory of the Federalist, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1984. ISBN 9780226212999

- Kesler, Charles R. Saving the Revolution: The Federalist Papers and the American Founding, New York: 1987. ISBN 9780029197301

- Patrick, John J., and Clair W. Keller. Lessons on the Federalist Papers: Supplements to High School Courses in American History, Government and Civics, Bloomington, IN: Organization of American Historians in association with ERIC/ChESS, 1987. ED 280 764. ISBN 9780941339001

- Schechter, Stephen L. Teaching about American Federal Democracy, Philadelphia: Center for the Study of Federalism at Temple University, 1984. ED 248 161. ISBN 9780916111007

- Yarbrough, Jean. "The Federalist." This Constitution: A Bicentennial Chronicle, 16 (1987): 4-9. SO 018 489.

- White, Morton. Philosophy, The Federalist, and the Constitution, New York: 1987. ISBN 9780195039115

- Wills, Gary. Explaining America: The Federalist, Garden City, NJ: 1981. ISBN 9780385146890

- Hamilton, Alexander, and Clinton Lawrence Rossiter. The Federalist papers; Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, John Jay. [New York]: New American Library 1961. ISBN 9780451619075

External links

All links retrieved April 4, 2017.

- Online text of Federalist No. 10 at The Founders' Constitution, hosted by the University of Chicago.

- Online text of Brutus, no. 1

- Online text of Cato, no. 3

- Teaching the Federalist Papers

- Federalist Papers on the Bill of Rights

- The Federalist Papers at the Library of Congress

- Fully Linkable version of The Federalist Papers

- The Federalist Papers etext from Project Gutenberg

- The Avalon Project at Yale Law School: The Federalist Papers

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 01:11:37 | 17 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Federalist_papers | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF