Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig

From Nwe

From Nwe

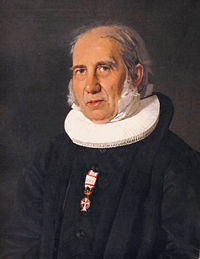

| N. F. S. Grundtvig | |

Portrait of N. F. S. Grundtvig

|

|

| Born | September 8 1783 Udby, Sjælland |

|---|---|

| Died | September 2 1872 (aged 88) Copenhagen |

| Occupation | Lutheran pastor, hymn-writer, and educator |

Nikolaj Frederik Severin Grundtvig (September 8, 1783 – September 2, 1872) (pronounced [ˈneg̊olaɪ̯ˀ ˈfʁaðˀʁæg̊ ˈsɛʋəʁin ˈg̊ʁɔnd̥ʋi]), most often referred to as simply N. F. S. Grundtvig, was a Danish teacher, writer, poet, philosopher, historian, pastor, and politician. He is one of the most influential people in Danish history, his philosophy giving rise to a new form of nationalism in Denmark in the last half of the nineteenth century. He was married three times, the last time in his seventy-sixth year.

A man of many talents, Grundtvig translated Beowulf into Danish without any formal training in Anglo-saxon literature. He was an influential churchman in his own right who also became the object of Soren Kierkegaard's criticism for his emphasis on the celebratory aspects of Christianity—as opposed to Kierkegaard's emphasis on sin, the "sickness unto death." Grundtvig was perhaps even more influential for his role in the creation of the folk high school.

For this development Grundtvig and his followers, Grundtvigians, are credited with playing a very influential role in the formulation of modern Danish national consciousness. Their attitude is well illustrated in the very different reaction of Danes to their national defeat in the Second Schleswig War, in 1864, against Prussia compared to the national trauma of German defeat in World War I.

Biography

Called Frederik rather than Nikolaj by those close to him, N. F. S. Grundtvig was the son of a Lutheran pastor, Johan Ottosen Grundtvig. He was brought up in a very religious atmosphere, although his mother also had great respect for old Norse legends and traditions. He was schooled in the tradition of the European Enlightenment, but his faith in reason was shaken by German romanticism and the history of the Nordic countries.[1]

In 1791, he was sent to live at the house of a pastor in Jutland, Laurids Feld, and studied at the Cathedral School of Aarhus from 1798 until he graduated left for Copenhagen in 1800 to study theology, and he was accepted to the University of Copenhagen in 1801.[2][3] At the close of his university life, he began to study Icelandic and the Icelandic Sagas, until in 1805, he took the position of tutor in a house on the island of Langeland. The next three years were spent in the study of Shakespeare, Schiller, Schelling and Fichte.[4] His cousin, the philosopher Henrich Steffens, had returned to Copenhagen in 1802 full of the teaching of Schelling and his lectures and the early poetry of Adam Oehlenschläger, opening the eyes of Grundtvig to the new era in literature.[5] His first work, On the Songs in the Edda, attracted no attention.

Returning to Copenhagen in 1808 he achieved greater success with his Northern Mythology, and again in 1809, with a long reading drama, The Fall of the Heroic Life in the North. The boldness of the ecclesiastical views was expressed in his first sermon in 1810, which was a passionate denunciation of the clergy of the city.[6] He had originally preached the sermon at an examination under the presence of one university professor, who described it as excellent, but when Grundtvig published the sermon three weeks later it offended the ecclesiastical authorities, and they demanded that he be punished.[6][7]

In 1810, a violent religious crisis converted him to Lutheranism and he retired to his father's country parish in Udby.[8] His new found conviction was expressed in his The First World Chronicle (Kort Begreb af Verdens Krønike i Sammenhæng) of 1812, a presentation of European history in which he attempts to explain how God is at throughout human history and in which he gives ideological criticisms of many prominent Danes.[9][10] It won him notoriety among his peers and lost him several friends, notably the historian Christian Molbech.[10] Upon his Father's death in 1813, he applied to be his successor but was rejected. In the following years his rate of publication was staggering: aside from a continuing stream of articles and poems, a number of books including two more histories of the world (1814 and 1817), the long, historical poem Roskilde-Riim (Rhyme of Roskilde) (1813) and a book-sized attempt at writing a commentary to it, Roskilde Saga.[11] From 1816 to 1819, he was editor of and almost sole contributor to a philosophical, poetical, and polemical journal entitled Danne-Virke.[9]

From 1813 to 1815, he attempted to form a movement with purpose of supporting the Norwegians against the Swedes, and later preached on how the weakness of the Danish faith was the cause of the loss of Norway in 1814 to an enthusiastic congregation in Copenhagen, but without his own parish, and as more and more churches barred him from preaching, he withdrew from the pulpit.[12] He resumed his preaching briefly in 1821, after he was granted the country living of Præstø, returning to the capital the year after. In 1825, he published a pamphlet, The Church's Rejoinder (Kirkens Gienmæle), a reply written in the name of the church to a work on the doctrines, rites, and constitutions of Protestantism and Catholicism by H. N. Clausen, Professor of Theology in the University of Copenhagen. Clausen had argued that although the Bible was the foundation principle of Christianity, it was in inself an inadequate expression of its full meaning, and he described the church as a "community for the purpose of advancing general religiousness."[13] In his reply, Grundtvig denounced Clausen as an anti-Christian teacher, arguing that Christianity is not a theory to be derived from the bible and elaborated by scholars and questioning the right of theologists to interpret the Bible.[14] Grundtvig was publicly prosecuted for libel and fined, and for seven years he was forbidden to preach, years which he spent in publishing a collection of his theological works, in paying three visits to England (1829-31), and in studying Anglo-Saxon.

In 1832, he obtained permission to preach again, and in 1839, he became pastor of the workhouse church of Vartov hospital, Copenhagen, a post he continued to hold until his death. Between 1837 and 1841, he published Sang-Værk til den Danske Kirke (Song Work for the Danish Church), a rich collection of sacred poetry; in 1838, he brought out a selection of early Scandinavian verse; in 1840, he edited the Anglo-Saxon poem of "The Phoenix," with a Danish translation. He visited England a third time in 1843.

From 1844 until after the First Schleswig War, Grundtvig took a very prominent part in politics, developing from a conservative into an absolute liberal position. In 1861, he received the titular rank of bishop, but without a see. He went on writing till his death, and preached in Vartov every Sunday until a few days before his death. His preaching attracted large congregations, and he soon had a following. His hymn-book effected a great change in Danish church services, substituting the hymns of the national poets for the slow measures of the orthodox Lutherans. All in all, Grundtvig wrote or translated about 1500 hymns, including "God's Word Is Our Great Heritage."

Christian thinking

Grundtvig's theological development is long and took a number of important turns throughout his life from the initial "Christian Awakening" of 1810 to the congregational and sacramental Christianity of his later years. He is usually identified with and most famous for the latter. He always called himself a pastor, not a theologian, reflecting the distance between him and the academic theology. The chief characteristic of his theology was the substitution of the authority of the "living word" for the apostolic commentaries, and he desired to see each congregation a practically independent community.

Thinking on education

Grundtvig is the ideological father of the folk high school though his own ideas on education had another focus. He advocated reforming the ailing Sorø Academy into a popular school aiming at another form of higher education than what was common at the university. Rather than educating learned scholars it was to educate its students for active participation in society and popular life. Thus practical skills as well as national poetry and history would form an essential part of the instruction. This idea came very close to implementation during the reign of Christian VIII, whose wife Caroline Amalie was an ardent supporter of Grundtvig, but the death of the monarch in 1848, and the dramatic political development in Denmark during this and the following years put an end to these plans. At that time, however, the first folk high school had already been established by one of his followers, Kristen Kold.

Grundtvig's ambitions for school reform were not limited to the popular folk high school. He also dreamed of forming a Great Nordic University (The School for Passion) to be situated at the symbolic point of intersection between the three Scandinavian countries in Gothenburg, Sweden. The two pillars of his school program, The School for Life (folk high school) and The School for Passion (university) were aimed at quite different horizons of life. The popular education should mainly be taught within a national and patriotic horizon of understanding, yet always keeping an open mind towards a broader cultural and intercultural outlook while the university should work from a strictly universal, that is, a humane and scientific, outlook. The common denominator of all Grundtvig's paedagogical efforts was to promote a spirit of freedom, poetry and disciplined creativity within all branches of educational life. He promoted soft values like wisdom, compassion, identification, and equality. And he opposed all compulsion, including exams, as deadening to the human soul. Instead he advocated unleashing human creativity according to the universally creative order of life. Only "willing hands make light work." Therefore a spirit of freedom, cooperation and discovery is to be kindled in individuals, in science and in the civil society as a whole.

Beowulf and Anglo-Saxon literature

In 1815, Grímur Jónsson Thorkelin published the first edition ever of the Epic of Beowulf titled De Danorum rebus gestis secul. III & IV : Poëma Danicum dialecto Anglosaxonica with a Latin translation. Despite his lack of any prior knowledge of Anglo-Saxon literature Grundtvig quickly discovered a number of flaws in Thorkelin's rendering of the poems. After a heated debate with Thorkelin, Johan Bülow, who had sponsored Thorkelin's work, offered to support a renewed translation by Grundtvig this time into Danish. The result, Bjovulfs Drape (1820), was the first modern language translation of Beowulf. The extensively surviving literature of the Anglo-Saxons, in Old English and in Latin, which he went on to explore, opened up for Grundtvig the spirituality of the early Church in the north and its articulation in poetry and prose, setting before him ancient models of Christian and universal historiography (notably the eighth century Latin Ecclesiastical History of Bede).

Using the resources of the Royal Library in Copenhagen and of the libraries of Exeter, Oxford and Cambridge in three successive summer visits to England (1829-31), he went on to make transcriptions (with a view to major publications which were, however, never realized) of two of the four great codices of Anglo-Saxon poetry, the Exeter Book and the codex designated Junius 11 in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. Beowulf and Anglo-Saxon literature continued to be a major source of inspiration throughout Grundtvig's life and had a wide-ranging influence upon his work.[15]

Legacy

Grundtvig holds a unique position in the cultural history of his country; he has been styled the Danish Carlyle and he might also be compared to Emerson. But his style of writing and fields of reference are not immediately accessible to a foreigner, thus his international importance does not match his contemporaries Hans Christian Andersen and Søren Kierkegaard.

He is commemorated as a bishop and a renewer of the church in the Calendar of Saints of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America on September 2.

Influence on Kierkegaard

Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard was profoundly influenced by Grundtvig. Like Hegel, he used Grundtvig as a touchstone and intellectual adversary. "Grundtvig's theology was diametrically opposed to Kierkegaard's in tone. Grundtvig emphasized the light, joyous, celebratory, and communal aspects of Christianity, whereas Kierkegaard emphasized seriousness, suffering, sin, guilt, and individual isolation." Kierkegaard attempted to steer the Danish Church away from Grundtvig's influence, but to no avail.

Bibliography

Editions

Grundtvig's secular poetical works were published in a nine volume edition. The first seven volumes by his second son, the philologist Svend Hersleb Grundtvig. The philological practice of this work, however, is not up to the standards of modern philology. His hymns have been collected in the philologically more stable five volume edition Grundtvigs Sang-Værk. The best overall collection of his writings is Holger Begtrup's 10 volume edition Udvalgte Skrifter. His enormous oeuvre is presented in Steen Johansen: Bibliografi over N.F.S. Grundtvigs Skrifter .

No comprehensive foreign language edition of his work exists. A three volume edition in German, however, is under preparation and projects aiming at an English edition are in progress as well.

The most important editions are:

- Grundtvigs Sang-Værk 1-6. Magnus Stevns (and others, editors). Copenhagen: Det danske Forlag. 1948-1964.

- Poetiske Skrifter 1-9. Udgivet af Svend Grundtvig (and others, editors). Copenhagen: Karl Schönberg og Hyldendal. 1880-1930.

- Udvalgte Skrifter 1-10. Holger Begtrup (editor). Copenhagen: Gyldendal. 1904-1909.

- Værker i Udvalg 1-10. Hal Koch and Georg Christensen (editors). Copenhagen: Gyldendal. 1940-1946.

- Steen Johansen: Bibliografi over N.F.S. Grundtvigs Skrifter 1-4. Copenhagen: Gyldendal. 1948-1954.

Further reading

In English

- A. M. Allchin (1998). N.F.S. Grundtvig. An Introduction to his Life and Work. London: Darton, Longman and Todd. ISBN 87-7288-656-0. The single most important work on Grundtvig in English.

- A. M. Allchin, ed. Heritage and Prophecy: Grundtvig and the English-Speaking World. ISBN 1-85311-085-X. Essays by leading international Grundtvig scholars.

- S. A. J. Bradley, tr., ed. (2008). N. F. S. Grundtvig: A Life Recalled. An Anthology of Biographical Source-Texts. Aarhus University Press. ISBN 978-87-7288-969-6. Very extensive Index documents the broad context of Grundtvig's life and work. Complementary to Allchin (1998).

Important, too, are the numerous articles in English published in the yearbook Grundtvig-Studier (Grundtvig Studies) from 1948 and onwards. Danish is the main language of the journal, but the English articles are prominent and increasing in recent years.

In other languages

The most important works on Grundtvig are a series of dissertations published since the founding of Grundtvig-selskabet (The Grundtvig Society). All of them contain summaries in major languages, most of them in English. This series includes:

- Aarnes, Sigurd Aa. (1960). Historieskrivning og livssyn hos Grundtvig. Oslo: Universitetforlaget. OCLC 250140171

- Auken, Sune (2005). Sagas spejl. Mytologi, historie og kristendom hos N.F.S. Grundtvig. Copenhagen: Gyldendal. ISBN 87-02-03757-2

- Bugge, Knud Eyvin (1965). Skolen for livet. Copenhagen: GAD. OCLC 68398348

- Christensen, Bent (1998). Omkring Grundtvigs Vidskab. Copenhagen: GAD. ISBN 87-12-03246-8

- Grell, Helge (1980). Skaberånd og folkeånd. Copenhagen: Grundtvig-Selskabet. ISBN 87-7457-072-2

- Grell, Helge (1987). Skaberordet og billedordet. Aarhus: Anis. ISBN 87-981073-0-5

- Heggem, Synnøve Sakura (2005): Kjærlighetens makt, maskerade og mosaikk. En lesning av N. F. S. Grundtvigs "Sang-Værk til den Danske Kirke". Oslo.

- Høirup, Henning (1949). Grundtvigs Syn på Tro og Erkendelse. Copenhagen: Gyldendal. OCLC 2699819

- Lundgreen-Nielsen, Flemming (1980). Det handlende ord. Copenhagen: GAD. ISBN 87-503-3464-6

- Michelsen, William (1954). Tilblivelsen af Grundtvigs Historiesyn. Copenhagen: Gyldendal. OCLC 2970196

- Thaning, Kaj (1963). Menneske først—Grundtvigs opgør med sig selv. Copenhagen: Gyldendal. OCLC 2670733

- Toldberg, Helge (1950). Grundtvigs symbolverden. Copenhagen: Gyldendal. OCLC 2684950

- Vind, Ole (1999). Grundtvigs historiefilosofi. Copenhagen: Gyldendal. ISBN 87-00-37308-7

Notes

- ↑ Arthur MacDonald Allchin, N. F. S. Grundtvig (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 1997, ISBN 87-7288-656-0).

- ↑ Finn Abrahamowitz, Grundtvig Danmark til lykke (Danish) (Copenhagen: Høst & Søns Forlag, 2000, ISBN 87-14-29612-8).

- ↑ Reich, 33

- ↑ Allchin, 31-32.

- ↑ Ebbe Kløvedal Reich, Solskin og Lyn—Grundtvig og hans sang til livet (Danish) (Copenhagen: Forlaget Vartov, 2000, ISBN 87-87389-00-2).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Allchin, p. 33

- ↑ Reich, 48.

- ↑ Allchin, 33-36.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Allchin, 39.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Abrahamowitz, 115-117.

- ↑ Abrahamowitz, 125-133.

- ↑ Reich, 55-57.

- ↑ Allchin, 105.

- ↑ Allchin, 105-106.

- ↑ S.A.J. Bradley, “Grundtvig, Bede and the Testimony of Antiquity,” Grundtvig Studier 2006: 110-31.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Abrahamowitz, Finn. 2000. Grundtvig Danmark til lykke (Danish). Copenhagen: Høst & Søns Forlag. ISBN 87-14-29612-8.

- Allchin, Arthur Macdonald. 1997. N. F. S. Grundtvig. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. ISBN 87-7288-656-0.

- Reich, Ebbe Kløvedal. 2000. Solskin og Lyn—Grundtvig og hans sang til livet (Danish). Copenhagen: Forlaget Vartov. ISBN 87-87389-00-2.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 13:13:25 | 12 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Nikolaj_Frederik_Severin_Grundtvig | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF