Adolf Hitler

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia | Adolf Hitler | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal life | |

| Date and place of birth | April 20, 1889 Braunau am Inn, Austria–Hungary |

| Parents | Alois Hitler (Schicklgruber) Klara Hitler |

| Claimed religion | Roman Catholic (rejected), Pantheism,[1] Atheism,[2] Evolutionism |

| Education | Realschule Linz, Austria |

| Spouse | Eva Braun |

| Children | none |

| Date & Place of Death | April 30, 1945 (aged 56) Berlin, Germany |

| Manner of Death | Suicide by gunshot |

| Place of burial | none, burned. |

| Dictatorial career | |

| Country | Germany |

| Military service | 16th Bavarian Reserve Regiment Imperial German Army (1914-1918) |

| Highest rank attained | Obergefreiter (Lance Corporal/Private First Class) |

| Political beliefs | Socialism National Socialism (Nazism) |

| Political party | German Workers' Party (Deutsche Arbeiterpartei 1919–1920) National Socialist German Workers' Party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei 1920–1945) |

| Date of dictatorship | March 23, 1933 |

| Wars started | World War II in Europe |

| Number of deaths attributed | 12,000,000+ exclusive of battle casualties

20,000,000 to 25,000,000 altogether Rummel: 21,000,000 |

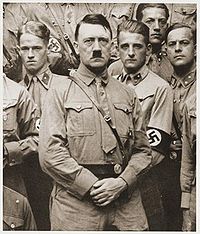

Adolf Hitler (April 20, 1889 – April 30, 1945) was the Austrian-born Chancellor of Germany from January 30, 1933, and the Führer of Germany from August 2, 1934 until his death on April 30, 1945. He was also the leader of the National Socialist German Workers' Party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei; NSDAP or Nazi Party) which gained political power through threat, intimidation, and outright violence throughout Germany in the aftermath of the First World War. He was born and baptized as a Roman Catholic, but he never took religion seriously beyond initially rebelling against his Catholic father by showing preferences for Lutheran Protestantism in predominantly Catholic Austria, as well as using quasi-religious rhetoric in his book, Mein Kampf and in speeches in order to not lose potential religious supporters and voting blocs. He was far more interested in Social Darwinism. After having minor wounds from an assassination bombing attempt in 1944, Hitler abused drugs originally intended to help with his injuries long after he had recovered from his injuries.

Hitler in his youth was a financially-irresponsible Bohemian (a German word of the time roughly the same as the English term "Hippy") who became broke after spending his father's inheritance wandering around Austria as a watercolour artist, practicing vegetarianism, and rarely attempting to seek serious employment. Hitler worked with a Jewish art dealer and after being rejected entry into Vienna's leading art school due to his unoriginal art, Hitler was a complete failure and broke. Rather than accept responsibility for his Bohemian lifestyle, Hitler in denial and increasing signs of the mental illness of psychosis, followed the political current in Europe at the time of blaming Jews for exploiting him. Hitler used the teachings of Martin Luther to promote his anti-Semitic views, similar to the other ways used by the Nazi Party in their effort to reshape and present to the public a much modified version of Christianity. One which promoted racial purity and Nazi ideology under the false banner known as "positive Christianity." The anti-Semites in Germany refused to acknowledge that Luther, prior to his seeing the Jew's refusal of his outreach to accept the Gospel, was highly sympathetic towards the Jews. It was adopted by a number of misguided Protestants and others who accepted the culture when it did not conform to biblical teachings.

Hitler being rebellious to his Catholic father took up a brief interest in Lutheranism and may have been influenced by Luther's anti-Semitic remarks. Hitler without any prospects sought to be conscripted into the German Army (but refused to serve the Austrian army due to many Jews being in it), there Hitler mixed his anti-Semitic views with some of the anti-Semitic factional-Lutheran conservative nationalist aspects (that left-wing historians exaggerate by calling Hitler "far right") in order to be accepted amongst conservative German army officers but also began to adopt radical socialist ideas as revolutionary socialist movements in Germany and elsewhere grew in strength.

After World War I, Hitler acted as an army political agent to investigate a small pan-German nationalist party called the German Workers' Party that used the anti-Semitic factional-Lutheran nationalist theme in combination with a revolutionary socialist agenda that denounced Jews as being responsible for capitalism, exploitation of Germany, and for Germany losing World War I. It was anti-Marxist - though only because Karl Marx was a Jew and due to their anti-Semitic hatred, and saw Marx as no different than capitalist Jews. The Party was disorganized and Hitler with his strong anti-Semitism took advantage of the situation and used demagoguery to raise himself in the party. In February 1920 the party changed its name to the National Socialist German Workers' Party (or Nazi Party). He used the party and its members to exact revenge for his psychotic perception of Jews and capitalists as having ruined him in his youth, along with the belief that weak civilian leaders and Jews were responsible for Germany's loss in the First World War, and his psychotic, megalomaniac view of himself as being the "Leader" (German: Führer) of Germany. Many leaders of the Nazi Party were mentally-unbalanced people with delusions of grandeur of both themselves and Germany, such as Heinrich Himmler, and Hermann Göring who was a morphine addict and an animal rights activist who preferred to have Jews used for scientific experiments.

Due to the thematic influence of the historic anti-Semitic faction of conservative Lutheran extremists on the Nazi movement, left-wing Marxist historians have exaggerated the role of conservative Lutherans in the Nazi movement and because of it claim that the Nazis are "far right." They completely ignore and deny the far left socialist parts of the Nazis, out of political dogmatism just as the Nazis themselves completely denied the socialist elements of Marxism because Marx was Jewish. And left-wing historians almost always neglect to note the very clear similarity of Hitler's loose Bohemian lifestyle as a youth to that of Hippies.

Adolf Hitler was an evolutionary racist and socialist (see also: evolutionary racism).[3][4][5] Hitler's policies and beliefs resulted in the mass extermination of the Jews, Gypsies, and other peoples he considered “inferior” throughout central and eastern Europe and were directly responsible for the outbreak of World War II, which caused the deaths of untold millions on and off the battlefield and reportedly ended only after Hitler's suicide in his Berlin bunker.

Contents

- 1 Early life

- 2 Who and what he was

- 3 Beliefs

- 4 Similarities between Communism, Nazism and liberalism

- 5 War

- 6 Path to power

- 7 The Beer Hall Putsch

- 8 Rebuilding the Nazi Party

- 9 In power

- 10 Anschluss and the Munich Agreement

- 11 Poland

- 12 Barbarossa

- 13 Beginning of the end

- 14 Death

- 15 See also

- 16 External links

- 17 Further reading

- 18 References

- 19 Sources

Early life[edit]

Hitler was born on April 20, 1889, in Braunau am Inn, Austria. Hitler's father, Alois (born 1837), was a customs official who was himself born out of wedlock, carrying for a time his mother's name, Schicklgruber. Evidence uncovered by Hans Frank, Hitler's lawyer, indicates that Alois's father, and by extension, Adolf's grandfather from this affair was a Jewish man named Frankenberger.[6] By 1876 he had his baptismal entry corrected in his church records, establishing his father as Johan Heidler, which was altered slightly to Hitler.

When his father retired, the family moved to Linz, Austria, where it remained a favorite for young Adolf for the rest of his life, and where he gave his wish to be buried. When Alois died in 1903 he left enough of a pension to support his wife and children; Adolf would take his and live off of it in Vienna after leaving school, dreaming of becoming an artist. Although somewhat competent as a painter of landscapes and architecture, his renderings of humans were considered “lifeless” and “crude” by the standards of the Academy of Fine Arts, and his application was rejected twice. Remaining in Vienna, he moved from one cheap flop house to another, painting postcards and advertisements to earn a meager living after his allowance had dried up. By then he had developed traits which characterized his life as a whole: secretiveness, loneliness, a Spartan mode of everyday life, and a hatred of the cosmopolitan, multinational character that was the makeup of Vienna. He never sought a proper job or regular employment. Instead he immersed himself in the works of Hegel, Nietzsche, and the anti-Semitic writings of the Englishman Houston Stewart Chamberlain. He loved the operas of Wagner, and the stories of the Nordic Gods... In early 1910, he entered a shelter for the homeless, populated in the main by poor Jews, on Meldemenstrasse, and was eating at soup kitchens. By this time he had pawned all his belongings.[7]

Who and what he was[edit]

Elie Wiesel wrote famously, and most eloquently about Hitler in 1998:

"At the same time that he terrorized his adversaries, he knew how to please, impress and charm the very interlocutors from whom he wanted support. Diplomats and journalists insist as much on his charm as they do on his temper tantrums. The savior admired by his own as he dragged them into his madness, the Satan and exterminating angel feared and hated by all others, Hitler led his people to a shameful defeat without precedent. That his political and strategic ambitions have created a dividing line in the history of this turbulent and tormented century is undeniable: there is a before and an after. By the breadth of his crimes, which have attained a quasi-ontological dimension, he surpasses all his predecessors: as a result of Hitler, man is defined by what makes him inhuman. With Hitler at the head of a gigantic laboratory, life itself seems to have changed."

"How did this Austrian without title or position manage to get himself elected head of a German nation renowned for its civilizing mission? How to explain the success of his cheap demagogy in the heart of a people so proud of having inherited the genius of a Wolfgang von Goethe and an Immanuel Kant?"

"Was there no resistance to his disastrous projects? There was. But it was too feeble, too weak and too late to succeed. German society had rallied behind him: the judicial, the educational, the industrial and the economic establishments gave him their support. Few politicians of this century have aroused, in their lifetime, such love and so much hate; few have inspired so much historical and psychological research after their death. Even today, works on his enigmatic personality and his cursed career are best sellers everywhere. Some are good, others are less good, but all seem to respond to an authentic curiosity on the part of a public haunted by memory and the desire to understand."

"We think we know everything about the nefarious forces that shaped his destiny: his unhappy childhood, his frustrated adolescence; his artistic disappointments; his wound received on the front during World War I; his taste for spectacle, his constant disdain for social and military aristocracies; his relationship with Eva Braun, who adored him; the cult of the very death he feared; his lack of scruples with regard to his former comrades of the SA, whom he had assassinated in 1934; his endless hatred of Jews, whose survival enraged him — each and every phase of his official and private life has found its chroniclers, its biographers."

"And yet. There are, in all these givens, elements that escape us. How did this unstable paranoid find it within himself to impose gigantic hope as an immutable ideal that motivated his nation almost until the end? Would he have come to power if Germany were not going through endless economic crises, or if the winners in 1918 had not imposed on it conditions that represented a national humiliation against which the German patriotic fiber could only revolt? We would be wrong to forget: Hitler came to power in January 1933 by the most legitimate means. His Nationalist Socialist Party won a majority in the parliamentary elections. The aging Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg had no choice but to allow him, at age 43, to form the new government, marking the end of the Weimar Republic. And the beginning of the Third Reich, which, according to Hitler, would last 1,000 years."

"From that moment on, events cascaded. The burning of the Reichstag came only a little before the openings of the first concentration camps, established for members of the opposition. Fear descended on the country and squeezed it in a vise. Great writers, musicians and painters went into exile to France and the U.S. Jews with foresight emigrated toward Palestine. The air of Hitler's Germany was becoming more and more suffocating. Those who preferred to wait, thinking that the Nazi regime would not last, could not last, would regret it later, when it was too late."

"The fact is that Hitler was beloved by his people — not the military, at least not in the beginning, but by the average Germans who pledged to him an affection, a tenderness and a fidelity that bordered on the irrational. It was idolatry on a national scale. One had to see the crowds who acclaimed him. And the women who were attracted to him. And the young who in his presence went into ecstasy. Did they not see the hateful mask that covered his face? Did they not divine the catastrophe he bore within himself?[9]

Beliefs[edit]

According to Albert Speer, Hitler never left the Catholic Church, but was hostile to its teachings. He did admire its power. Hitler only mentioned Christianity in his speeches to gain votes and favor. He and Nazi Party also presented to the public what was known as "positive Christianity," which in reality was only an attempt to mold Christian theology to match Hitler's world view. The "Protestant Reich Church" promoted racial purity, excluded many parts of the Bible, stated that Jesus was not Jewish but Nordic, while proclaiming Hitler as the "new messiah." In the end, any voiced tolerance of true Christianity during the 1930s changed to targeted persecution, mainly of Protestant "resisters" to Nazism.[10]

Although Hitler may have had some Christian rhetoric in his speeches, he certainly rejected it on a personal level. In the book, Hitler's Table Talk, it reveals that Hitler thought of Christianity as a great "scourge" of history.[11]

In Hitler's Table Talk, which were published in 1953, it was revealed that Hitler, at some point, embraced atheism while rejecting Christianity as an invention of Judaism, which he held similar animosity toward:

| “ | And while many atheists make the preposterous claim that Adolf Hitler was a Christian, his private diaries, first published in 1953 by Farrar, Straus and Young, reveal clearly that the Führer was a rabid atheist: "The heaviest blow that ever struck humanity," Hitler stated, "was the coming of Christianity. Bolshevism is Christianity’s illegitimate child. Both are inventions of the Jew… Our epoch will certainly see the end of the disease of Christianity."[2] | ” |

Hitler, Nazism and socialism[edit]

For more information please see: Nazism and socialism The Ludwig von Mises Institute declares:

| “ | The identification of Nazi Germany as a socialist state was one of the many great contributions of Ludwig von Mises...

The basis of the claim that Nazi Germany was capitalist was the fact that most industries in Nazi Germany appeared to be left in private hands. What Mises identified was that private ownership of the means of production existed in name only under the Nazis and that the actual substance of ownership of the means of production resided in the German government. For it was the German government and not the nominal private owners that exercised all of the substantive powers of ownership: it, not the nominal private owners, decided what was to be produced, in what quantity, by what methods, and to whom it was to be distributed, as well as what prices would be charged and what wages would be paid, and what dividends or other income the nominal private owners would be permitted to receive. The position of the alleged private owners, Mises showed, was reduced essentially to that of government pensioners. De facto government ownership of the means of production, as Mises termed it, was logically implied by such fundamental collectivist principles embraced by the Nazis as that the common good comes before the private good and the individual exists as a means to the ends of the State. If the individual is a means to the ends of the State, so too, of course, is his property. Just as he is owned by the State, his property is also owned by the State.[4] |

” |

Hitler and the Theory of Evolution[edit]

For more information please see: Evolutionary racism and Social effects of the theory of evolution

The staunch evolutionist Stephen Gould admitted the following:| “ | [Ernst] Haeckel was the chief apostle of evolution in Germany.... His evolutionary racism; his call to the German people for racial purity and unflinching devotion to a "just" state; his belief that harsh, inexorable laws of evolution ruled human civilization and nature alike, conferring upon favored races the right to dominate others; the irrational mysticism that had always stood in strange communion with his brave words about objective science - all contributed to the rise of Nazism. - Stephen J. Gould, "Ontogeny and Phylogeny," Belknap Press: Cambridge MA, 1977, pp.77-78.[13] | ” |

Robert E.D. Clark in his work Darwin: Before and After wrote concerning Hitler's evolutionary racism:

| “ | The Germans were the higher race, destined for a glorious evolutionary future. For this reason it was essential that the Jews should be segregated, otherwise mixed marriages would take place. Were this to happen, all nature’s efforts 'to establish an evolutionary higher stage of being may thus be rendered futile' (Mein Kampf).[14] | ” |

Hitler wrote in Mein Kampf:

| “ | The stronger must dominate and not blend with the weaker, thus sacrificing his own greatness. Only the born weakling can view this as cruel, but he, after all, is only a weak and limited man; for if this law did not prevail, any conceivable higher development (Hoherentwicklung) of organic living beings would be unthinkable.[3] | ” |

Dr. Robert E.D. Clark wrote in his work Darwin, Before and After the following regarding Hitler and the theory of evolution: “Adolf Hitler’s mind was captivated by evolutionary teaching — probably since the time he was a boy. Evolutionary ideas — quite undisguised — lie at the basis of all that is worst in Mein Kampf — and in his public speeches”.[15]

Richard Hickman in his work Biocreation concurs and wrote the following:

| “ | It is perhaps no coincidence that Adolf Hitler was a firm believer in and preacher of evolutionism. Whatever the deeper, profound, complexities of his psychosis, it is certain that [the concept of struggle was important for]. . . his book, Mein Kampf clearly set forth a number of evolutionary ideas, particularly those emphasizing struggle, survival of the fittest and extermination of the weak to produce a better society.[17] | ” |

Noted evolutionary anthropologist Sir Arthur Keith conceded the following in regards to Hitler: “The German Führer, as I have consistently maintained, is an evolutionist; he has consciously sought to make the practices of Germany conform to the theory of evolution”.[15]

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Marilynne Robinson wrote the following regarding Hitler's racism in the November 2006 issue of Harper’s magazine:

| “ | While it is true that persecution of the Jews has a very long history in Europe, it is also true that science in the twentieth century revived and absolutized persecution by giving it a fresh rationale — Jewishness was not religious or cultural, but genetic. Therefore no appeal could be made against the brute fact of a Jewish grandparent.

[Richard] Dawkins deals with all this in one sentence. Hitler did his evil "in the name of ... an insane and unscientific eugenics theory." But eugenics is science as surely as totemism is religion. That either is in error is beside the point. Science quite appropriately acknowledges that error should be assumed, and at best it proceeds by a continuous process of criticism meant to isolate and identify error. So bad science is still science in more or less the same sense that bad religion is still religion. That both of them can do damage on a huge scale is clear. The prestige of both is a great part of the problem, and in the modern period the credibility of anything called science is enormous. As the history of eugenics proves, science at the highest levels is no reliable corrective to the influence of cultural prejudice but is in fact profoundly vulnerable to it. There is indeed historical precedent in the Spanish Inquisition for the notion of hereditary Judaism. But the fact that the worst religious thought of the sixteenth century can be likened to the worst scientific thought of the twentieth century hardly redounds to the credit of science.[18][19] |

” |

Evolutionist and new atheist Richard Dawkins stated in an interview: “What’s to prevent us from saying Hitler wasn’t right? I mean, that is a genuinely difficult question."[16] The interviewer wrote, regarding the Hitler comment, "I was stupefied. He had readily conceded that his own philosophical position did not offer a rational basis for moral judgments. His intellectual honesty was refreshing, if somewhat disturbing on this point."[16]

Hitler may have been an atheist[edit]

Adolf Hitler is theorized to be an atheist.[20][21][22] He reportedly loathed Christianity, and his father considered having faith a "scam".[23]

Richard Weikart, Professor of Modern European History, California State University Stanislaus, theorizes that Hitler was a pantheist (which is a type of atheism).[24] See the video: What were Hitler’s religious beliefs? by Richard Weikart

Adolf Hitler and abortion[edit]

For more information see: Abortion and Adolf Hitler

In 1942 Adolf Hitler declared:

| “ | In view of the large families of the Slav native population, it could only suit us if girls and women there had as many abortions as possible. We are not interested in seeing the non-German population multiply…We must use every means to instill in the population the idea that it is harmful to have several children, the expenses that they cause and the dangerous effect on woman's health… It will be necessary to open special institutions for abortions and doctors must be able to help out there in case there is any question of this being a breach of their professional ethics.[25] | ” |

(The atheist Marquis de Sade is credited with providing the first notable impetus to introduce abortion into western society. See: Abortion and atheism)

Other beliefs[edit]

Hitler supported animal "rights"[26][27][28] and environmentalism,[28][29][30] and that support was reflected in the laws created during the Third Reich. Hitler also enacted gun control laws.[31][32]

Similarities between Communism, Nazism and liberalism[edit]

See also: Similarities between Communism, Nazism and liberalism

| Communist Manifesto | Nazi Party Platform | Analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | "Abolition of property in land and application of all rents of land to public purposes." | "We demand an agrarian reform in accordance with our national requirements, and the enactment of a law to expropriate the owners without compensation of any land needed for the common purpose. The abolition of ground rents, and the prohibition of all speculation in land." | The stripping away of land from private owners. Liberalism today demands "eminent domain" on property. |

| 2 | "A heavy progressive or graduated income tax." | "We demand the nationalization of all trusts...profit-sharing in large industries...a generous increase in old-age pensions...by providing maternity welfare centers, by prohibiting juvenile labor...and the creation of a national (folk) army." | The points raised in the Nazi platform demand an increase in taxes to support them. Liberalism today demands heavy progressive and graduated income taxes. |

| 3 | "Abolition of all rights of inheritance." | "That all unearned income, and all income that does not arise from work, be abolished." | Liberalism today demands a "death tax" on anyone inheriting an estate. |

| 4 | "Confiscation of the property of all emigrants and rebels." | "We demand that all non-Germans who have entered Germany since August 2, 1914, shall be compelled to leave the Reich immediately." | The Nuremberg Laws of 1935 allowed Germany to take Jewish property. |

| 5 | "Centralisation of credit in the hands of the state, by means of a national bank with State capital and an exclusive monopoly." | "We demand the nationalization of all trusts." | Central control of the financial system. |

| 6 | "Centralisation of the means of communication and transport in the hands of the State." | "We demand that there be a legal campaign against those who propagate deliberate political lies and disseminate them through the press...editors and their assistants on newspapers published in the German language shall be German citizens...Non-German newspapers shall only be published with the express permission of the State...the punishment for transgressing this law be the immediate suppression of the newspaper..." | Central control of the press. Liberals today demand control or suppression of talk radio and Fox News. |

| 7 | "Free education for all children in public schools. Abolition of children’s factory labour in its present form. Combination of education with industrial production, &c, &c." | "In order to make it possible for every capable and industrious German to obtain higher education, and thus the opportunity to reach into positions of leadership, the State must assume the responsibility of organizing thoroughly the entire cultural system of the people. The curricula of all educational establishments shall be adapted to practical life. The conception of the State Idea (science of citizenship) must be taught in the schools from the very beginning. We demand that specially talented children of poor parents, whatever their station or occupation, be educated at the expense of the State. " | Central control of education, with an emphasis on doing things their way. Liberals today are doing things their way in our schools. |

War[edit]

By 1913 Hitler was in Munich, Germany, with war clouds on the horizon. Classified as unfit for service in the Austrian army (possibly by faking, as he did not like the thought of serving Austria) in 1914, he volunteered for the German Army, joining the 16th Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment, greeting the war with enthusiasm, and finding the military discipline and comradeship satisfying. He served during the entire First World War as a messenger carrying dispatches between units, and often at the front lines under fire; he was wounded in 1916, and gassed in 1918. His bravery during this time earned him the Iron Cross, 2nd Class, in December, 1914, and in August 1918 he was awarded the Iron Cross, 1st Class – a rare decoration for a corporal. But the gassing would take him out of the war and into a hospital, where he would be told the heart-wrenching news of Germany's defeat the following November.

Path to power[edit]

After the war ended, Hitler's future seemed uncertain. There was much discontent among demobilized veterans because of the lack of employment. The German military had felt it had not been defeated; indeed, the German Army stood on foreign soil when the Armistice was signed November 11, 1918 and not a square inch of German soil had been occupied. This was despite the fact that the German Army's strongest position, the Hindenburg line, had been broken by the Allies, and the German Army itself was in full retreat. However, the army felt they had done their job, and the nation had been "stabbed in the back" by a gang of traitors made up of civilian political leaders who betrayed the Fatherland. The "myth" that Germany had been defeated was the "big lie" Hitler spoke of, as if repeating it often enough would cause people to believe it.

After his discharge from the hospital, Hitler acted as an army political agent, assigned in Munich to gather information on the various political parties which had spring up amid the social chaos following Germany's defeat. In September 1919, he was given orders to investigate the relatively-minor German Workers' Party (Deutsche Arbeiterpartei; DAP); intrigued by the party's apparatus and its racial, pan-German nationalism, he joined, becoming its 55th member. He remained on the army payroll until he was discharged in March 1920. By then, the party had changed its name to the National Socialist German Workers' Party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei; NSDAP) or Nazi Party. Hitler had already devoted himself to improving the party's propaganda, as well as his own position within.

Conditions in Germany fostered the development of the party. Economic woes brought widespread discontent, added to the furor surrounding the loss of the war and the harsh terms heaped upon Germany by the Allied Powers in the Versailles Peace Treaty. Bavaria's traditional separatism from the central government in Berlin made current conditions especially sharp, and Hitler was savvy enough to take full advantage of them. When he joined, he found the party ineffective in leadership and uncertain as to its aims; he accepted the party program, but regarded it as a means to an end. He caused friction with other members of the party, and their attempts to control him caused a threat of resignation; realizing that the future of the party now depended on Hitler, who clearly had a talent of organization, fund collecting, and above all, speaking, they declined to accept it; from July, 1921 Hitler was the party leader with nearly unlimited power. From his party newspaper, Völkischer Beobachter ("Popular Observer"), he spewed out propaganda. The meetings where he spoke grew from mere handfuls to hundreds, and then to thousands. A man of charismatic personality, he quickly attracted a circle of loyal and devoted followers: Rudolf Hess, Hermann Göring, Julius Streicher, and Alfred Rosenberg.

Munich was also a gathering place for former servicemen dissatisfied with conditions in the country; members of the Freikorps, which had been organized after the war from army units that refused to return to civilian life; and those civilians who plotted against the republic. Many of these men joined the Nazi Party. Among them was a staff member of the district command who had joined the German Workers' Party before Hitler, Ernst Röhm, a pudgy man with a scared face who saw his own ambition in helping further Hitler's rise within the party. Röhm recruited what came to be known as the "Brown Shirts," the violent squads used by the Nazis to attack rival socialists, battle Communists, and to protect party meetings whenever Hitler was speaking. By 1921 they were organized into a private army of the Party called the Sturmabteilung, abbreviated to SA.

The Beer Hall Putsch[edit]

Germany in 1923 was marked by social and political unrest caused by hyperinflation. In this time Hitler was able convince Erich Ludendorff, an accomplished general and leader of the German forces in the first World War, to join him in a coup d'état (Putsch in German). When Hitler learned that the nationalist prime minister of Bavaria was giving a speech to 3000 officials in one of Munich's biggest beer halls (the Haufbrau Haus), he ordered his paramilitaries to surround the building. Hitler went inside and took the prime minister hostage, announced a revolution, and attempted to convince him to join the coup against Berlin and become member in his new administration. The Bavarian prime minister agreed under pressure, but informed the nation via radio later that night that he did not support Hitler. The prime minister also informed the federal government in Berlin; the putsch had begun to fail.

The next morning, 9 November 1923, Hitler and Ludendorff were marching with approximately 2000 partly armed supporters through Munich in a show of strength to regain the momentum. In the ensuing fight between Hitler's marchers and a cordon of police and army units at least 14 Nazi supporters and three policemen were killed and hundreds wounded. Ludendorff handed himself over to the authorities, while Hitler fled soon after the fighting began. Hitler was arrested a few days later at a friend's house, were had been in hiding since the failed coup. Ludendorff was acquitted of all charges, while Hitler was sentenced to 5 years in prison (he would serve eight months).[33][34] The Bavarian prime minister, who foiled the plan, was killed in 1934 in the "Night of the Long Knives."

Mein Kampf[edit]

For a more detailed treatment, see Mein Kampf.

Hitler had his inner circle as frequent visitors in his prison cell, which was made more comfortable due to his celebrity. While there, he dictated to Rudolf Hess the first volume of Mein Kampf (“My Struggle”), his political autobiography and a compendium of his many ideas, including his evolutionist ideas.

Hitler believed in the inequality of the races, nations, and individuals as part of the natural order of mankind, and chief among them was the exalted “Aryan race”, and the greatest of the Aryans were the Germans. It was the German, according to Hitler, that gave the world civilization and the arts; to safeguard the German people as a race (the “Volk”), they would need to be united under a single leader (the Führer), where they would be protected from their three principle enemies: Marxism, which included social democracy as well as communism; democracy and its mob-rule, as shown by the failings of the Weimar Republic; and above all what Hitler called the poisoners of humanity, the Jews. “Rational anti-Semitism must lead to systematic legal opposition,” he wrote in 1919. “Its final objective must be the removal of the Jews altogether.” In Mein Kampf, he told the world that the Jew was the “destroyer of culture,” “a parasite within the nation,” and “a menace.”

From Mein Kampf:

| “ | The Jew "... he blares out his merits to the rest of the world until people really begin to believe in them. Anyone who does not believe in them is doing him a bitter injustice. In a short time he begins to twist things around to make it look as if all the injustice in the world had always been done to him and not the other way around." [35] | ” |

| “ | Hitler portrays Jews as leaders in politics and banking, both groups seeking to strengthen their cause, Zionism, to ensure Jewish domination. From his Social Darwinist perspective, Hitler perceived a racial war as inevitable and he sought to halt the "Jewish drive towards world conquest"... As Berlin collapsed around him, Adolf asserted: "Out of the ruins of our towns and monuments hatred will grow against those finally responsible for everything, International Jewry." [36] | ” |

Zweites Buch[edit]

For a more detailed treatment, see Zweites Buch.

Hitler's second book, completed in 1928 but not published until 1961, expands on Hitler's Darwinian views and also puts on display overtones of Malthusianism.[37] In Zweites Buch, particularly chapter 1, he writes about issues in "living space," the "struggle for life," issues in food supply, and other common topics in overpopulation commentary.

Rebuilding the Nazi Party[edit]

Internal dissension within the party caused it to languish while Hitler was in prison. When released in December 1924, he saw difficulties in the country that had not existed before the Putsch, namely currency reform that brought economic stability, and the scaling back of the war reparations as a result of the Dawes Plan. Hitler was also forbidden to speak in public, and remained so until 1928; nonetheless he worked to rebuild the party and re-establish his own position within it as leader, despite Gregor Strasser's opposition in northern Germany. By 1927 the number of Nazis was in the hundreds of thousands.

A new period of political and economic instability began with the onset of the Great Depression which threw millions out of work in Europe and North America. To campaign against the Young Plan (a second renegotiation of war reparations payments) Hitler made an alliance with one of Germany's leading nationalists, Alfred Hugenberg, whose newspapers enabled Hitler to reach a national audience for the first time. The alliance also had another advantage: it enabled him to seek support from many in business and industry who controlled funds going into politics, and who themselves were desirous of seeing Germany under the control of a strong anti-Soviet and anti-Communist regime. The subsidies Hitler received placed the Nazi Party on a strong financial footing, enabling him to make his emotional appeal to the lower middle class and the unemployed in his faith that Germany would recover from its suffering and be a great nation once more. The alliance with the industrialists also demonstrated another aspect of Hitler, a skill of effectively using those that would use him, which many would discover when it was too late.

The electoral strength of the Nazis grew during the Depression, as unceasing propaganda accused the government of failing to improve conditions for the working man. By the fall of 1930 the Nazis captured more than 18 percent of the vote, compared to just 2.6 percent in 1928. Hitler captured 36.8 percent of the vote when he opposed Paul von Hindenburg in the 1932 presidential election; his mass following put him in such a strong position that he entered a series of closed-door intrigues with Franz von Papen, Oskar Hindenburg, and Otto Meissner, all sharing a fear and loathing of a communist government. Despite the party losing votes in the November, 1932 election, Hitler insisted on nothing less than the office of chancellor for himself. For him, it was all or nothing. Hindenburg offered it to him on January 30, 1933.

In power[edit]

Almost immediately, Hitler established himself as dictator. Less than a month after taking office, on February 27 the Reichstag building was set on fire under mysterious circumstances (officially blamed on a feeble-minded Dutch communist, Marinus van der Lubbe); Hitler soon after succeeded in getting several decrees passed removing much of the freedom guaranteed the constitution in the name of state security, and which also allowed an intensified campaign of violence against dissidents. Incredibly, in a special election set in those conditions on March 5, the Nazis won 43.9 percent of the vote. On March 21, the new Reichstag assembled at the Potsdam Church, as much a show of unity between the old guard under Hindenburg and the Nazis as it was a show of peace. Two days later the Enabling Act was passed, giving Hitler full powers; with the exception of the Nazis, all other political parties, including those which had helped pass the Enabling Act, ceased to exist within three months. Many of their leaders were imprisoned in concentration camps.

Night of the Long Knives[edit]

Hitler, however, did not wish to start an immediate revolution. In order to implement his ideas he still needed the support of the army. But he did have one growing problem that was a thorn in the army's side, the three million-plus men of the SA and their leader, Ernst Röhm, who wanted nothing less than to merge the SA into the much smaller army, with himself in overall command. At first, Hitler tried getting Röhm's support by persuasion, but Hitler's inner circle was for removing him by any means possible. On June 29, 1934, Hitler ordered a purge, flew towards a resort near Munich where a number of SA leaders were vacationing, and had them all arrested; many would be shot without trial. Refusing to shoot himself when offered, Röhm was killed in his cell at Dachau, his last words, ironically, “Mein Führer, mein Führer!” [38][39][40] The purge took place between June 30 and July 2, 1934.

On July 13, Hitler gave speech in the Reichstag, announcing that some seventy-four individuals had been shot for threatening the stability of the Reich.

- "If anyone reproaches me and asks why I did not resort to the regular courts of justice, then all I can say is this: In this hour I was responsible for the fate of the German people, and thereby I became the supreme judge of the German people…It was no secret that this time the revolution would have to be bloody; when we spoke of it we called it 'The Night of the Long Knives.' Everyone must know for all future time that if he raises his hand to strike the State, then certain death is his lot."

Hitler also used this event to settle his account with other opponents, such as Georg Strasser, who stood for a more socialist and less racist national socialism, and the former Bavarian prime minister who foiled the Beer Hall Putsch in 1923. Satisfied that the SA leadership was thoroughly broken up (thousands of SA members were either arrested or killed that night), the army approved of Hitler's actions. Hindenburg died a few days later on August 2, and Hitler merged the office of president with the chancellorship, and with it the supreme command of the German armed forces. During this time the world was slowly recovering economically from the Depression, but it quickened in Germany, coincidently with Hitler's rise to power. Taking credit for the recovery made him very popular, bringing him a 90 percent approval rating in a voter plebiscite that year.

Beginnings of expansion[edit]

In matters of state, the running of domestic affairs was left to subordinates, which was something Hitler had little attention for. Foreign policy always peaked his interest, in so much as to the advantages of a “Greater Germany”, which was his chief ambition. The first part of realizing this, according to Mein Kampf, was to be a reunion of the German peoples within Europe; the second would be an expansion of Germany to the east (lebensraum). Expanding would mean a renewed conflict with the Slavic peoples, whom Hitler intended to serve as slaves to the “New German Order.” To follow through on his ambitions, he would have to remove Poland and the Soviet Union as countries; France also would have to be stabilized in the west, as she was Germany's enemy for more than a century. He counted as possible allies Italy, with its fascist government under Benito Mussolini, and Britain, whom he regarded as having a similar, Teutonic heritage.

Before any of his ambitions could take place, there was one thing he detested which needed immediate removal: the restrictions placed upon Germany by the Treaty of Versailles at the end of World War I. Posing as a man of peace to allay suspicions, he insisted that he was a champion of Europe wishing only for the removal of the inequalities leveled by the treaty, and posturing as a shield against Bolshevism. In October, 1933, he had Germany withdraw from the League of Nations. The following January he signed a non-aggression treaty with Poland. His individual repudiations of parts of the treaty were followed by offers of negotiations for new agreements, while maintaining Germany's limited ambitious nature.

While this was going on, Germany was steadily building up the armed forces. Rigorous training using wooden guns and trucks marked as “tanks” got needed battlefield training for officers. Potential fighter pilots began their training in gliders at public demonstrations – Germany, under terms of the treaty, was not allowed an air force – and later they would fly in new civilian stunt planes and transports, which on the drawing board were designed to be rapidly turned into fighters and bombers. Conscription was introduced in January, 1935, and in June of that year Hitler successfully signed a naval treaty with Britain, giving him rights to a respectable navy; but even while the ink was drying, Germany was secretly building a large U-boat fleet.

The matter of reuniting the German peoples came into being in July, 1934, and here Hitler overreached. German organizations were covertly aiding Austrian Nazis in the overthrow of their government, culminating in an attempted revolt as well as murdering Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss. When the attempt clearly failed, Hitler denied involvement. In January, 1935, a plebiscite was introduced in the Saarland; more than 90 percent voted to return the territory to Germany. Then in March, 1936, came his greatest slap to the Versailles Treaty: against the advice of his generals, and in open defiance of France and Britain, he ordered troops into the demilitarized Rhineland. Germany was once again becoming the leading power in continental Europe. By October, 1936, Germany had signed an alliance with Italy, proclaiming a “Rome-Berlin axis,” followed by the Anti-Comintern Pact with Japan. All three countries would sign a single, mutual alliance pact, the following year.

Anschluss and the Munich Agreement[edit]

Removed from their offices in January 1938 were Hjalmar Schacht (economic ministry); Werner von Fritsch (soldiers’ representative); and Konstantin von Neurath (foreign office); the reason being was they were not fully accepting of Nazism. Beginning his plans of German conquest, he started with Austria. Kurt von Schuschnigg, the Austrian chancellor, was invited to Berchtesgaden in February, where he was browbeaten and forced to sign an agreement placing Austrian Nazis in the government. When Schuschnigg resisted and announced a plebiscite for Austrian voters concerning independence, Hitler ordered German troops into Austria, completely taking over the country within days. His return to Vienna was in triumph; enthusiastic crowds greeted him by the tens of thousands, in sharp contrast to the scenes of privation he had gone through there in his youth. Austria was annexed (Anschluss) to the Reich a short time later.

While the Anschluss was going on, Hitler was speaking in friendly terms with Czechoslovakia; nearly as soon as Austria ceased to exist, Hitler proceeded with his plans against the Czechs. The northwestern region of Czechoslovakia was the Sudetenland, inhabited by a German minority, and the leader of them, Konrad Henlein, was instructed to make impossible demands for those Germans on the Czech government. In the interest of preventing a general war (which Hitler wanted), Mussolini and British prime minister Neville Chamberlain concluded a peaceful agreement in Munich on September 30, giving Hitler the Sudetenland without firing a shot. Chamberlain would return to Britain, waiving the agreement signed between himself and Hitler, declaring it to be “peace for our time”, but his act of appeasement would ensure the peace would last only a few more months. Despite assurances that the Sudetenland was his last territorial demands, “Czechia”, as the remainder of Czechoslovakia was called, became a German protectorate on March 15, 1939, when Hitler ordered it occupied. Just over a week later, Lithuania was forced to cede to Germany the territory of Memel (Klaipeda), on the border of East Prussia.

Poland[edit]

Poland's turn was next, and listening to the rumblings was France and Britain, which signed guarantees of mutual assistance to the Polish nation should it be attacked by Germany. Hitler also signed pacts: a “Pact of Steel” with Italy, strengthening the alliance between Rome and Berlin, and then a treaty that caught many off-guard: a non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union on August 23. A secret clause in the pact allowed for the simultaneous invasion of Poland, and the division of the country in the center from north to south. Poland was invaded on September 1; two days later, Britain and France declared war on Germany.

Hitler assumed his own war strategy. Poland was conquered within weeks, and when a desired peace accord with Britain failed to materialize, he ordered the army to prepare for a western offensive. Norway was invaded and occupied, forestalling a British move on that country; Denmark was occupied by April, 1940. Hitler than adopted General Erich von Manstien's plan for an offensive against France itself, which would move through neutral Belgium's Ardenne Forest on May 10, taking that country as a matter of convenience, as well as avoiding the static fortifications of France's Maginot Line. The German forces, extremely successful in their operations, reached the coastal ports on the English Channel in 10 days; Holland and Belgium both surrendered within days. But south of Dunkirk was where the army was ordered to halt. Hitler had hoped even at this stage in the battle that Britain would commit to peace; instead, the halting of the German army allowed the British to remove 170,000 fighting men.

On June 10, Italy entered the war as German tanks were sweeping across northern France. Hitler signed an armistice with France on June 22, the signing taking place in the same rail car at the same site where the Germans surrendered in 1918.

Having failed in getting the British to sign an armistice, Hitler prepared his forces for “Operation Sea Lion,” the invasion of Britain. However, the Luftwaffe was defeated in its attempt to gain air superiority over British airspace, also known as the Battle Of Britain, which forced the permanent postponement of Sealion.

Facing the failure of the British to give in, Hitler started to prepare to double-cross his erstwhile partner in the Poland conquest, Joseph Stalin and the Soviet Union. Then Mussolini invaded Greece, got bogged down in the Balkans, and the threat loomed that he would lose his whole army there. Hitler found it necessary to come to his aid, while at the same time taking direct control of Yugoslavia in the wake of the overthrow of the pro-Nazi government.

Barbarossa[edit]

The attack on Soviet Russia began June 22, 1941. Rapid in its advancement, the German army captured a large swath of territory between the Baltic and Black seas, and captured close to 3,000,000 prisoners. But Hitler, already micromanaging military operations, became overbearing to his generals; he preferred to go after many targets, while his generals argued for a single objective. A few miles in front of Moscow, the German army was halted by a Russian offensive in December, as well as something he had absolutely no control over: the severe Russian winter.

In the lands already occupied by German forces, S.S. chief Heinrich Himmler was preparing the ground for Hitler's new German order. Expelling the Jews from Germany was the first step, and this was carried out by laws and decrees beginning in 1933; the Germans would switch to outright force in 1939, as Jews were first deported en-masse to Poland, then walled into ghettos after the occupation began. By 1941, a policy crafted under S.S. general Reinhard Heydrich had changed expulsion for extermination in what was called "a final solution to the Jewish question" (die Endlösung der Judenfrage). The system of concentration camps was supplemented by the creation of specialized killing centers in the occupied countries, especially in Poland, where camps such as Auschwitz, Treblinka, Sobibor, and Belzac “processed” thousands of victims daily. Some six million Jews died during what was called the Holocaust, as well as an additional five million Slavs, Gypsies, the handicapped, the aged, and many others that the Nazis considered “subhuman” in accordance with German racial policies.[41]

Beginning of the end[edit]

Hitler grew increasingly strained by the end of 1942, depending on large amounts of drugs supplied by his physician, Theodor Morell, as a result of the twin defeats of El Alamein (which he lost the bulk of his Afrika corps to British general Montgomery), and Stalingrad (where he lost an entire army of 250,000 men to the Russians). He spent more time in his headquarters in East Prussia, and his time in the public eye ceased to exist. He refused to visit bombed German cities, and, as with Stalingrad, refused to allow German armies to withdraw from the battlefield when the situation was lost. Still, he could make stunning, decisive decisions when called for, such as the commando raid that resulted in the rescue of Benito Mussolini from Italian partisans in July, 1943.

But the defeat of Germany in the war was looming closer. Hitler's relations with his leading commanders grew strained, the more so as he allowed units of the S.S. to take positions traditionally held by the army. The line at the eastern front was slowly being pushed back by the Soviets, while in the Atlantic his U-boats campaign had faltered. German cities were constantly being bombed, and a successful invasion on the Normandy coast of France in June, 1944 marked the beginning of the end.

Assassination attempt[edit]

Seeing Germany's chances of surviving the war were desperate, a group of officers plotted to assassinate Hitler, planning several attempts in 1943–44, but nearly successful on July 20, 1944, when a bomb hidden in a briefcase by Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg went off under a table that Hitler and others were leaning over; four were killed outright, several suffered injuries, but Hitler escaped relatively unharmed (the bomb itself was set down away from Hitler behind a solid oak table leg, saving him). The conspirators were quickly rounded up; Stauffenberg was shot. The remainder were put on show trials and condemned to hang on meat hooks with piano wire. It was said that Hitler enjoyed watching film of their executions. As a result of the bomb, Nazi members were employed at key positions within the army, removing any trace of the army's independence.

Within months nearly all of the territory occupied by Germany was now in Allied hands. A last offensive in December, 1944 to take the port of Antwerp, Belgium, failed. Hitler had by then grown ill; his hopes for a German victory bordered on the fantastical and the imagination. By January, 1945 he had moved into his command bunker in Berlin, where he gave orders deploying fictional divisions to counter the ever-closer Soviets. When all seemed lost, he gave out his final orders: first, appointing Admiral Karl Dönitz as head of the state and his successor, and Josef Goebbels as chancellor; and second, dictating his last political will which was an attempt to justify his life's work.

On April 29, he committed the one truly-chivalrous act of his life: he married Eva Braun, his long-time mistress. After retiring to his room in the bunker the next day, Eva took poison, and Hitler put a bullet in his head. In accordance with his wishes, both bodies were burned. His Third Reich would outlive him for another week.

Elie Wiesel wrote the following in Time Magazine regarding Hitler:

| “ | Adolf Hitler or the incarnation of absolute evil; this is how future generations will remember the all-powerful Führer of the criminal Third Reich. Compared with him, his peers Mussolini and Franco were novices. Under his hypnotic gaze, humanity crossed a threshold from which one could see the abyss. "Before Hitler, we thought we had sounded the depths of human nature," argues Ron Rosenbaum, author of "Explaining Hitler." "He showed how much lower we could go, and that's what was so horrifying. It gets us wondering not just at the depths he showed us but whether there is worse to come. The power of Hitler was to confound the modernist notion that judgments about good and evil were little more than matters of taste, reflections of social class and power and status. Although some modern scholars drive past the notion of evil and instead explain Hitler's conduct as a reflection of his childhood and self-esteem issues, for most survivors of the 20th century he is confirmation of our instinctive sense that evil does exist. It moves among us; it leads us astray and deploys powerful, subtle weapons against even the sturdiest souls." [9] | ” |

All in all, Hitler survived over forty assassination attempts. The Stauffenburg attempt was the closest anyone ever came to killing Hitler. George Elser, a communist, came very close in 1938, having planted a bomb in a beam that Hitler stood in front of while giving a speech. Luck saved Hitler, as he left the hall early and twelve minutes later the bomb exploded.

Death[edit]

On the afternoon of April 30, 1945 as the Soviet Red Army closed in on the center of Berlin, Hitler and Eva Braun committed suicide.[42][43][44] The majority of contemporary historians have rejected the other accounts of Hitler's demise or reported escape from Berlin as either Soviet propaganda or surmise.[45][46] Following the end of the war, because of the different versions presented by the Soviet Union as to Hitler being dead and alive, both British Military Intelligence (led by agent Hugh Trevor-Roper) and the FBI conducted investigations as to the different claims made. The declassified information from British MI5, confirmed that Hitler shot himself.[47] The declassified FBI documents report a number of alleged sightings of Hitler along with theories that he and Eva Braun escaped to Argentina in a submarine and changed identity. However, as the report states, "because of lack of information to support the story advanced...it is believed impossible to continue efforts to locate Hitler."[48]

More recently in 2009, American researchers were allowed to perform DNA tests on the skull fragment the Russians claim was from Hitler. The tests revealed that the skull fragment belonged to a woman under 40 years of age who was not related to Eva Braun. However, the jaw fragments which had been recovered and identified as Hitler's[49] were not tested by the American researchers.[50] Therefore, most all historians are very skeptical and dismiss these popular conspiracy theories, in particular because there are credible witnesses, who saw the bodies of Hitler and Eva Braun.[46][51][52][53]

See also[edit]

External links[edit]

- Extracts From Mein Kampf by Hitler

- Mein Kampf by Adolf Hitler. Full text.

- Adolf Hitler ORIGINAL Watercolor Artworks.

- Hitler Was a Leftist

Further reading[edit]

- STATE MEDICAL SERVICES OF THE THIRD REICH, FROM THE OPENING STATEMENT BY TELFORD TAYLOR, Trials of War Criminals before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals under Control Council Law No. 10. Nuremberg, October 1946–April 1949. Washington, D.C.: U.S. G.P.O, 1949–1953. Retrieved from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

References[edit]

- ↑ Hitler's Religion: The Twisted Beliefs That Drove the Third Reich

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Today's atheists are bullies -- and they are doing their best to intimidate the rest of us into silence at Fox News

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 https://www.icr.org/index.php?module=articles&action=view&ID=268

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 http://mises.org/daily/1937

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 http://www.hourofthetime.com/socialist.htm

- ↑ https://www.jpost.com/Diaspora/Study-suggests-Adolf-Hitler-was-a-quarter-Jewish-597966

- ↑ Young Adolf: The Adolescent Hitler and Beyond.

- ↑ Hitler owned painting now in National Gallery

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 http://www.time.com/time/time100/leaders/profile/hitler.html"

- ↑ McNab, Chris. The Third Reich. (2009) pp. 182, 183

- ↑ http://www.catholiceducation.org/articles/facts/fm0110.htm (backup link here)

- ↑ https://creation.com/darwinism-and-the-nazi-race-holocaust

- ↑ http://members.iinet.net.au/~sejones/social.html

- ↑ http://www.creationontheweb.com/content/view/1675

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 http://www.christiancourier.com/articles/read/the_holocaust_why_did_it_happen

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 http://byfaithonline.com/page/in-the-world/richard-dawkins-the-atheist-evangelist

- ↑ http://www.creationism.org/csshs/v08n3p24.htm

- ↑ http://solutions.synearth.net/2006/10/20

- ↑ http://www.uncommondescent.com/intelligent-design/someone-finally-said-it-dawkinss-hysterical-scientism/

- ↑ https://creation.com/review-hitlers-religion-weikart

- ↑ http://www.thomism.org/atheism/atheist_murderers.html

- ↑ https://www.trueorigin.org/hitler01.php

- ↑ https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2019/04/20/hitler-hated-judaism-he-loathed-christianity-too/

- ↑ What were Hitler’s religious beliefs? by Richard Weikart

- ↑ https://www.lifesitenews.com/ldn/2007/sep/07090708.html

- ↑ [ https://books.google.com/books?id=e7FME0btkH0C&pg=PA62&lpg=PA62&dq=hitler+animal+rights&source=bl&ots=PIxjDRDBj1&sig=tbJisPm39hMcxj1g6xL0Kh0sn7g&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi3qZP7xOPTAhVr4oMKHeTMA_c4FBDoAQhKMAc#v=onepage&q=hitler animal rights&f=false Animal Rights: Current Debates and New Directions], pg. 62.

- ↑ Harrison, David; Paterson, Tony (September 22, 2002). Thanks to Hitler, hunting with hounds is still verboten. The Telegraph. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Washington, Ellis (March 26, 2011). The Nazi Cult of the Organic'. WND. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ↑ Nazi "Ecology", Frank Furedi, columbia.edu. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ↑ Musser, Mark (February 6, 2016). Yale Professor on Nazi Environmentalism: So Close, yet So Far. American Thinker. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ↑ Wolverton, II, J.D., Joe (January 30, 2017). Nazi Gun Control Laws: a Familiar Road to Citizen Disarmament? The New American. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ↑ Stupp, Herbert W. (July 13, 2015). Hitler and Gun Control. The American Spectator. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- ↑ http://history1900s.about.com/cs/thirdreich/a/beerhallputsch_2.htm

- ↑ http://www.historyplace.com/worldwar2/timeline/putsch2.htm

- ↑ Mein Kampf by Adolf Hitler.

- ↑ Mein Kampf – The Text, its Themes and Hitler’s Vision Robert Carr dissects a book frequently referred to but seldom read.

- ↑ The Rise of the Nazis: Second Edition

- ↑ http://www.historyplace.com/worldwar2/timeline/roehm.htm

- ↑ http://www.adolfhitler.ws/lib/nsdap/Rohm.html [Dead link]

- ↑ http://www.dhm.de/lemo/html/nazi/innenpolitik/roehm/index.html

- ↑ http://www.historyplace.com/worldwar2/riseofhitler/burns.htm

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian. Hitler: A Biography. (2008) p. 955

- ↑ Joachimsthaler, Anton. The Last Days of Hitler: The Legends, the Evidence, the Truth. (1999) [1995] pp. 160-182

- ↑ Beevor, Antony. Berlin – The Downfall 1945. (2002) p. 359

- ↑ Eberle, Henrik and Uhl, Matthias. The Hitler Book. (2005) p. 282

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Joachimsthaler. The Last Days of Hitler: The Legends, the Evidence, the Truth. (1999) [1995] pp. 160-182, 240-260

- ↑ https://www.mi5.gov.uk/home/about-us/who-we-are/mi5-history/world-war-ii/hitlers-last-days.html

- ↑ https://vault.fbi.gov/adolf-hitler/adolf-hitler-part-01-of-04/view

- ↑ Eberle and Uhl. The Hitler Book. (2005) p. 282

- ↑ https://www.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/europe/12/10/hitler.skull.debate/index.html?_s=PM:WORLD

- ↑ https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2050137/Did-Hitler-Eva-Braun-flee-Berlin-die-old-age-Argentina.html

- ↑ Fischer, Thomas. Soldiers of the Leibstandarte. (2008) p. 47

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian. Hitler 1936-1945 - Nemesis. (2000) p. 1038

Sources[edit]

Psychological Analysis of Adolf Hitler, His Life and Legend, Walter C. Langer, Office of Strategic Services, Washington, D.C.

Categories: [Dictators] [Mass Murderers] [Nazis] [Evolutionists] [Totalitarianism] [Anti-Semitism] [Bigotry] [German History] [World War II] [Evolutionary Racists] [Russophobia] [War Criminals] [Socialists] [Liberal Authors] [Former Christians] [Austrian Politicians] [Perpetrators of Cancel Culture] [Gun Control proponents] [Abortion Advocates] [Conspiracy Theorists]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/05/2023 07:47:49 | 105 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Adolf_Hitler | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF