Crucifix

From Nwe

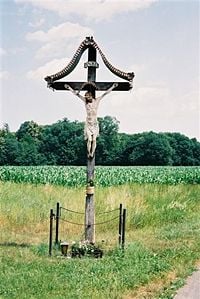

From Nwe A crucifix (from Latin cruci fixus, meaning "one fixed to a cross") is a cross with a representation of Jesus' body, or corpus. It is a principal symbol of the Christian religion, primarily used in the Catholic, Anglican, and Eastern Orthodox Churches. It emphasizes Christ's sacrifice—his death by crucifixion, his subsequent resurrection, and the grace and rebirth that he offers to believers. This history of the crucifix goes back to the beginning of Christianity, and Christ's death on the cross. However, it was originally seen as a grotesque symbol, a sign of death. It was only over time that the crucifix, through its many phases, was imbued with the meanings it now holds for Christian believers.

The crucifix is a reminder of the trials and tribulations that human beings face and the hope that comes from the redemption offered through Christ's death on the cross to those who believe. It is a fusion of art and faith, and has been a consistent symbol of Catholicism for over 1500 years.

Overview

A crucifix is commonly regarded as a depiction of the death of Jesus Christ by crucifixion. As such, a representation of Jesus is placed upon a cross of similar proportions to those used by Romans during crucifixions. It can be represented in painting, sculpture, metalwork, and other material art forms. It is often the principal ornament placed upon the altar in a Catholic sanctuary.[1] It is commonly referred to and displayed on Christian monuments. Crucifixes often adorn rosaries and are a source of inspiration for many Christians. A crucifix is often inscribed with the letters INRI, an acronym for (translated from Latin), "Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews." A crucifix serves as a symbol and a reminder of Christ's journey to earth, his trials and death at the hands of humanity, and his victory over death. It signifies the choice people are given to believe in Jesus or not to believe. It can also represent his brutal death, offering an example for people to follow during hard times or difficult tasks. There are almost countless meanings that can be derived from the crucifix, and as such, there are numerous styles that have crept into Christian art over the past 2000 years.

On some crucifixes, a skull and crossbones are shown below the corpus, referring to Golgotha (Calvary), the site at which Jesus was crucified—"the place of the skull." It was probably called "Golgotha" because it was a burial-place, or possibly because of a legend that the place of Jesus' crucifixion was also the burial place of Adam. The standard, four-pointed Latin crucifix consists of an upright stand and a crosspiece to which the sufferer's arms were nailed.

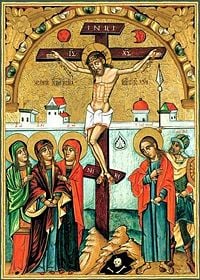

The Eastern Christian crucifix includes two additional crossbars: The shorter nameplate, located in the upper portion of the stand, to which INRI was affixed; and the stipes, near the bottom of the stand, to which the feet were nailed, which is angled upward toward penitent thief St. Dismas (to the viewer's left) and downward toward impenitent thief Gestas (to the viewer's right). It is thus eight-pointed. The majority of Eastern crucifixes tend to be two-dimensional icons that show Jesus as already dead, as opposed to the depictions of the still-suffering Jesus that can be found in some other Churches. Also, Eastern crucifixes have Jesus' two feet nailed side by side, rather than one atop the other, as Western crucifixes do. The crown of thorns is also generally absent in Eastern crucifixes.

Another depiction sometimes used portrays a triumphant risen Christ (clothed in robes, rather than stripped as for his execution) with arms raised, appearing to rise up from the cross, sometimes accompanied by "rays of light."

History

The image of the cross itself is nearly timeless, in both the East and the West, far predating Christianity itself in the form of two intersecting lines at right angles to each other.[2]

The word cross was introduced to English in the tenth century as the term for the instrument of the torturous execution of Christ (gr. stauros', xy'lon), gradually replacing rood, ultimately from Latin crux, via Old Irish cros. Originally, both "rood" and "crux" referred simply to any "pole," the later shape associated with the term being based in church tradition, rather than etymology. The word can nowadays refer to the geometrical shape unrelated to its Christian significance from the fifteenth century. "Crux" in Latin means cross, and it was a Roman device of torture on which they nailed a person to a wooden cross, an act called crucifying, and let the person die of asphyxiation while hanging from the cross.

While early Christians avoided the use of even this simple cross, not to mention any rendering of Jesus' crucifixion, the cross came into use no later than the fifth century, with archaeological evidence placing the first surviving image of a crucified Jesus in fifth-century Rome. Earlier renderings depicted Jesus as a lamb, and Christians tended to focus more on Jesus' divine attributes than his earthly presence. And yet, while there is little evidence to support it, there are references to Christians by the year 200 who would decorate themselves with a cross to differentiate themselves from Pagans during common daily life.[2]

In 629 C.E., the Council of Constantinople ordered that, "instead of the lamb, our Lord Jesus Christ will be shown hereafter in His human form in images so that we shall be led to remember His mortal life, His passion, and His death, which paid the ransom for mankind."[3] However, the crucifix itself would have to wait until the Middle Ages to find widespread popularity. In these images, Jesus was depicted with open eyes and a calm face—no trace of pain—reflecting the prevalent theological emphasis on the resurrection—and, hence, Jesus' immunity against suffering and death. By the thirteenth century, the crucifix had begun to show the body of Jesus as twisted and bleeding on the cross, as the importance of the incarnation and the humanity of Jesus grew. This new crucifix became the centerpiece in many churches and cathedrals, a favored object of contemplation. This may partially be because the medieval Catholic Church placed suffering at the heart of its salvation doctrine. Indeed, Catholics were expected to "crucify" their own human nature, in imitation of the suffering of Jesus.[4]

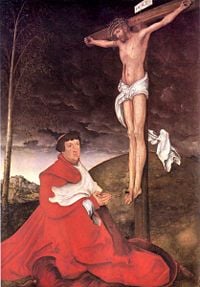

During the fifteenth century, Renaissance painters and sculptors further refined the image of Christ on the cross, representing Jesus with his arms outstretched and his head bowed and eyes closed, but his body no longer wretched and in pain. In accordance with the prevailing spirit of the day, Jesus often displayed serenity and grace. This Jesus was nothing less than an optimistic figure, standing in stark contrast with medieval interpretations. In this way, Jesus represented the earthly perfection of a new Adam.[4]

Protestants, however, took a dim view of the crucifix. This was reinforced during the Reformation, when Protestants repudiated most representational religious images. Hence, the cross became even more associated with Catholicism.[5] Strong reformationists saw the crucifix as an example of idolatry and tied it closely with the Catholic church. While this viewpoint has largely resolved in the last century or so, the crucifix is still seen as an object that is almost exclusively belonging to Catholic Christianity.

Crucifix vs. cross

Anglican, Roman Catholic, Orthodox, and Coptic Christians generally use the crucifix in public religious services. They believe the crucifix is in keeping with Scripture, which states that, “We preach Christ crucified, unto the Jews a stumbling block, and unto the Greeks foolishness.”[6]

Prayer in front of a cross or crucifix is often part of devotion for Christians, especially those worshiping in a church, and private devotion in a chapel. The person may sit, stand, or kneel in front of the crucifix, sometimes looking at it in contemplation, or merely in front of it with head bowed or eyes closed. In the Roman Catholic Mass, and Anglican Holy Eucharist, a procession begins Mass in which a crucifix is carried forward into the church followed by lector and servers, the priest, deacon, along with some of the other items used in the service such as the Gospels and the altar candles. Eastern Christian liturgical processions also include a crucifix at the head of the procession.

The crucifix is also considered by some to be one of the most effective means of averting or opposing demons, as stated by many exorcists, including the famous exorcist of the Vatican, Father Gabriele Amorth. In folklore it is considered to ward off vampires, incubi, succubi, and other evils.

It should be noted that a cross and crucifix are related, but not the same thing. While the crucifix does indeed use the symbol of the cross as its backbone, what makes it unique is the added element of Christ's body. There are those that believe that the empty cross is a more powerful symbol, as it emphasizes the fact that Christ is no longer there and his triumph over death. Most Protestant Christians who use the cross as a symbol use the empty cross. However, the Catholic tradition prefers to place emphasis on Christ's death for the sins of humanity—his resurrection would not have happened had he not died on the cross first. And, thus, this aspect of theology is emphasized in the crucifix.

In addition, the cross has also been viewed by some as a symbol of slavery and oppression. For instance, during the time of the inquisition, the Catharis were forced to wear yellow crosses on their clothes to represent their "heresy." In modern times, the Ku Klux Klan was notorious for using burning crosses to terrorize African-Americans. As a result of the cross' tarnished history, some modern groups, such as the Jehovah's Witnesses, reject the cross as essentially pagan in origin and dispute its early usage by Christians. They hold that the "cross" on which Jesus died was really a single-beamed "stake."

Types of crucifix

There are many different types of crucifixes, limited only by the imagination of the artists. Listed below are only two examples of the plethora of varieties.

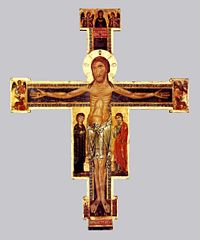

San Damiano Crucifix The San Damiano Crucifix was first designed by an eleventh or twelfth century Umbrian artist, adorning the chapel of San Damiano, in Assisi, Italy. Since that time innumerable variations have been made in similar a style. The San Diamiano crucifix depicts events seen in the Passion of Christ. At the top, Jesus ascends into Heaven, his hand outstretched towards the hand of his Father. The Virgin Mary and John stand to Christ's right. To Christ's left stand Mary Magdalen, Mary Cleophas (the mother of James), and a Roman Centurion.[7]

The Pardon Crucifix This crucifix was very important to Popes who granted indulgences, such as Pope Pius X. Whoever carried this crucifix was granted an indulgence. On the back of the crucifix are the words, "Father, forgive them." On the long arm of the cross are the words, "Behold this heart which has so loved men," and the Sacred Heart is then shown where the tow arms of the cross meet.[7]

See also

- Christianity

- Cross

- Crucifixion

Notes

- ↑ A.J. Schulte, "Altar Crucifix" from The Catholic Encyclopedia (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907). Retrieved August 16, 2008 from New Advent.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 O. Marucchi, Archæology of the Cross and Crucifix from The Catholic Encyclopedia (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908). Retrieved August 16, 2008 from New Advent.

- ↑ Roman Catholic Info, Catholic Crucifix Retrieved August 16, 2008.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Thomson Wadsworth, The Crucifix Retrieved August 16, 2008.

- ↑ Robert J Loescher, Crucifix, Cross: General Information Believe. Retrieved August 16, 2008.

- ↑ Jason A. Catania, Sermon for September 17, 2006 Mount Calvary Church. Retrieved August 16, 2008.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Fish eaters, Crucifixes and Crosses Retrieved August 16, 2008.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- International Congress on Medieval Studies, Søren Kaspersen, and Erik Thunø. Decorating the Lord's table: on the dynamics between image and altar in the Middle Ages. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, University of Copenhagen, 2006. ISBN 978-8763501330

- Kennedy, Katherine, and E. Hermitage Day. The crucifix: an outline sketch of its history. London: Mowbray, 1917. OCLC 2672911

- Laugerud, Henning, and Laura Katrine Skinnebach. Instruments of devotion: the practices and objects of religious piety from the late Middle Ages to the 20th century. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2007. ISBN 8779342000

- Scanlan, Michael. The San Damiano cross: an explanation. Steubenville, Ohio: Franciscan University of Steubenville, 2007. OCLC 123415362

External links

All links retrieved May 5, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 03:02:09 | 21 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Crucifix | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF