Death Valley National Park

From Nwe

From Nwe | Death Valley National Park | |

|---|---|

| IUCN Category II (National Park) | |

|

|

|

| Location: | California & Nevada, U.S. |

| Nearest city: | Pahrump, Nevada |

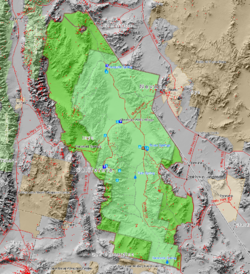

| Area: | 3,367,627.68 acres (13,628 km²) 3,348,928.88 acres (13,553 km²) federal |

| Established: | October 31, 1994 |

| Visitation: | 827,776 (in 2005) |

| Governing body: | National Park Service |

Death Valley National Park is a United States National Park located east of the Sierra Nevada mountain range, in California, and extending into Nevada. Geologically, it forms part of the southwestern portion of the Great Basin and is similar to other structural basins of the region. However, it is unique in its depth, with portions of the valley floor being the lowest land area in the Western Hemisphere. It is the hottest and driest of the national parks in the United States.

Covering some 5,270 square miles (13,650 square km—over 3.4 million acres), it is the largest national park in the country. Approximately 95 percent of the park is designated as wilderness and is home to many species of plants and animals that have adapted to the harsh desert environment. Some examples include Creosote Bush, Bighorn Sheep, Coyote, and the Death Valley Pupfish—a survivor from much wetter times.

The natural environment of the area has been profoundly shaped by its geology. The oldest rocks are extensively metamorphosed and at least 1.7 billion years old. Ancient warm, shallow seas deposited marine sediments until rifting opened the Pacific Ocean. Additional sedimentation occurred until a subduction zone formed off the coast. This uplifted the region out of the sea and created a line of volcanoes. Later this began to pull apart, creating the Basin and Range landform we see today.

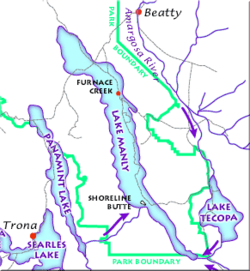

Geography

Within Death Valley National Park are two major valleys: Death Valley and Panamint Valley, both of which were formed within the last few million years and both bounded by north-south-trending mountain ranges. These and adjacent valleys follow the general trend of Basin and Range topography with one modification: There are parallel strike-slip faults that perpendicularly bound the central extent of Death Valley. The result of this shearing action is additional extension in the central part of Death Valley, which causes a slight widening and relatively more subsidence there.

Uplift of surrounding mountain ranges and subsidence of the Valley floor are both occurring. The uplift on the Black Mountains is so fast that the alluvial fans (fan-shaped deposits at the mouth of canyons) there are relatively small and steep compared to the huge alluvial fans coming off the Panamint Range. In many places, so-called "wine glass canyons" are formed along the Black Mountains front as a result. This type of canyon results from the mountain range's relatively fast uplift, which does not allow the canyons enough time to cut a classic V-shape all the way down to the stream bed. Instead, a V-shape ends at a slot canyon halfway down with a relatively small and steep alluvial fan on which the stream sediments collect.

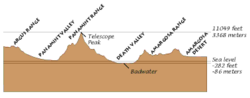

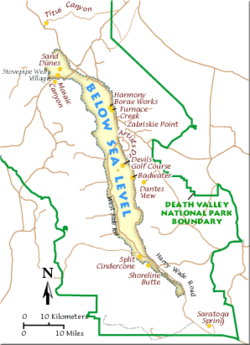

At 282 feet (86 m) below sea level, Badwater on Death Valley's floor is the second-lowest point in the Western Hemisphere (behind Laguna del Carbón in Argentina), while Mount Whitney, only 85 miles (140 km) to the west, rises to 14,505 feet (4,421 m). This topographic relief is the greatest elevation gradient in the contiguous United States, and is the terminus point of the Great Basin's southwestern drainage. Although the extreme lack of water in the Great Basin makes this distinction of little current practical use, it does mean that in wetter times the lake that once filled Death Valley (Lake Manly) was the last stop for water flowing in the region, meaning the water there was relatively saturated in dissolved materials. Thus, salt pans in Death Valley are among the largest in the world and are rich in minerals, such as borax and various salts and hydrates. The largest salt pan in the park extends 40 miles (65 km) from the Ashford Mill Site to the Salt Creek Hills, covering some 200 square miles (500 km²) of the Valley floor (Badwater, the Devils Golf Course, and Salt Creek are all part of this feature). The second-most well-known playa in the park is the Racetrack Playa, famous for its mysterious moving rocks.

Climate

Death Valley is one of the hottest and driest places in North America due to its lack of surface water and its low relief. On July 10, 1913, a record 134° F (57° C) was measured at the Weather Bureau's observation station at Greenland Ranch, which is the highest temperature ever recorded on the continent. Daily summer temperatures of 120° F (49° C) or greater are common, as well as nightly winter temperatures below freezing. July is the hottest month, with an average high of 114.9° F and an average low of 86.3° F. December is the coldest month, with an average high of 65.1° F and an average low of 37.5° F. The record low at the Furnace Creek Inn is 15° F. There are an average of 189.3 days annually with highs of 90° F or higher and 138 days annually with highs of 100° F or higher. Temperatures below freezing occur on an average of 11.7 days annually.

Several of the larger Death Valley springs derive their water from a regional aquifer, which extends as far east as southern Nevada and Utah. Much of the water in this aquifer was placed there many thousands of years ago, during the Pleistocene ice ages, when the climate was much cooler and wetter. Today's drier climate does not provide enough precipitation to recharge the aquifer at the rate at which water is being withdrawn.[1]

The highest range in the park is the Panamint Range, with Telescope Peak being its highest point at 11,049 feet (3368 m). Death Valley is a transitional zone in the northernmost part of the Mojave Desert and is five mountain ranges removed from the Pacific Ocean. Three of these are significant barriers: The Sierra Nevada, Argus Range, and the Panamint Range. Air masses tend to lose their moisture as they are forced up over mountain ranges, in what climatologists call a rain shadow effect. The exaggerated rain shadow effect for the Death Valley area makes it North America's driest spot, receiving about 1.7 inches (43 mm) of rainfall annually at Badwater, while some years fail to register any measurable rainfall. Annual average precipitation varies from 1.9 inches (48 mm) overall in the areas below sea level to over 15 inches (380 mm) in the higher mountains that surround the Valley. When rain does arrive, it often does so in intense storms causing flash floods which remodel the landscape and sometimes create very shallow ephemeral lakes.

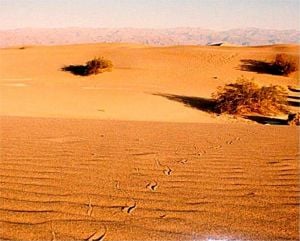

The hot, dry climate makes it difficult for soil to form. Mass wasting, the down-slope movement of loose rock, is therefore the dominant erosive force in mountainous areas, resulting in "skeletonized" ranges (literally, mountains with very little soil on them). Sand dunes in the park, while famous, are not nearly as numerous as their fame or dryness of the area may suggest. One of the main dune fields is near Stovepipe Wells in the north-central part of the Valley and is primarily composed of quartz sand. Another dune field is just 10 miles (16 km) to the north, but is instead mostly composed of travertine sand. Yet another dune field is near the seldom-visited Ibex Hill in the southernmost part of the park, just south of Saratoga Springs (a marshland). Prevailing winds in the winter come from the north, and prevailing winds in the summer come from the south. Thus, the overall position of the dune fields remain more or less fixed.

Biology

Habitat varies from saltpan 282 feet (86 m) below sea level to the sub-alpine conditions found on the summit of Telescope Peak, which rises to 11,049 feet (3,368 m). Vegetation zones include Creosote Bush, Desert Holly, and mesquite at the lower elevations and sage up through shadscale, blackbrush, Joshua Tree, pinyon-juniper, to Limber Pine and Bristlecone Pine woodlands. The saltpan is devoid of vegetation, and the rest of the valley floor and lower slopes have sparse cover, yet where water is available, an abundance of vegetation is usually present.

These zones and the adjacent desert support a variety of wildlife species, including 51 species of native mammals, 307 species of birds, 36 species of reptiles, three species of amphibians, and two species of native fish. Small mammals are more numerous than large mammals, such as Bighorn Sheep, Coyotes, Bobcats, Kit Foxes, Cougars, and Mule Deer. Mule Deer are present in the pinyon/juniper associations of the Grapevine, Cottonwood, and Panamint ranges. Bighorn Sheep are a rare species of mountain sheep that exist in isolated bands in the Sierra and in Death Valley. These are highly adaptable animals and can eat nearly any plant. They have no known predators, but humans and burros compete for habitat. The ancestors of the Death Valley Pupfish swam to the area from the Colorado River via a long since dried-up system of rivers and lakes. They now live in two separate populations: One in Salt Creek and another in Cottonwood Marsh.

One of the hottest and driest places in North America, nonetheless Death Valley is home to over 1,040 species of plants, and 23 species are endemic—found nowhere else in the world. Adaptation to the dry environment is key. For example, creosote bush and mesquite have tap-root systems that can extend 50 feet (15 m) down in order to take advantage of a year-round supply of ground water. The diversity of Death Valley's plant communities results partly from the region's location in a transition zone between the Mojave Desert, the Great Basin Desert, and the Sonoran Desert. This location, combined with the great relief found within the Park, supports vegetation typical of three biotic life zones:

- The lower Sonoran,

- The Canadian, and the

- Arctic/Alpine in portions of the Panamint Range.

Based on the Munz and Keck (1968) classifications, seven plant communities can be categorized within these life zones, each characterized by dominant vegetation and representative of three vegetation types: Scrub, desert woodland, and coniferous forest. Microhabitats further subdivide some communities into zones, especially on the Valley floor.

Unlike many locations across the Mojave Desert, many of the water-dependent Death Valley habitats possess a diversity of plant and animal species that are not found anywhere else in the world. The existence of these species is due largely to a unique geologic history and the process of evolution that has progressed in habitats that have been isolated from one another since the Pleistocene epoch.

Geologic history

The park has a diverse and complex geologic history. Since its formation, the area that comprises the park has experienced at least four major periods of extensive volcanism, three or four periods of major sedimentation, and several intervals of major tectonic deformation where the crust has been reshaped. Two periods of glaciation (a series of ice ages) have also had its effects on the area, although no glaciers ever existed in the ranges now in the park.

Little is known about the history of the oldest exposed rocks in the area due to extensive metamorphism (alteration of rock by heat and pressure). Radiometric dating gives an age of 1700 million years for the metamorphism (during the Proterozoic. Approximately 1400 million years ago, a mass of granite now in the Panamint Range intruded this complex. Uplift later exposed these rocks to nearly 500 million years of erosion.

The Pahrump Group of formations is several thousand feet (hundreds of meters) thick and was deposited from 1200 million to 800 million years ago. This was after uplift-associated erosion removed whatever rocks covered the Proteozoic-aged rock. Pahrump is composed of arkose conglomerate (stones in a concrete-like matrix) and mud stone, dolomite from carbonate banks topped by algal mats in stromatolites, and basin-filling sediment derived from the above including possibly glacial till from the Snowball Earth glaciation. The youngest rocks in the Pahrump Group are from basaltic lava flows.

A rift opened and subsequently flooded the region as part of breakup of the supercontinent Rodinia and the creation of the Pacific Ocean. A shoreline similar to that of the present Atlantic Ocean margin of the United States lay to the east. An algal mat-covered carbonate bank was deposited (this is now the Noonday Dolomite). Subsidence of the region occurred as the continental crust thinned and the newly formed Pacific widened, forming the Ibex Formation. An angular unconformity (an uneven gap in the geologic record) followed.

A true ocean basin developed to the west, breaking all the earlier formations along a steep front. A wedge of clastic sediment then started to accumulate at the base of the two underwater precipices, starting the formation of opposing continental shelfs. Three formations developed from sediment that accumulated on the wedge. The region's first known fossils of complex life are found in the resulting formations. Notable among these are the Ediacara fauna and trilobites.

The sandy mudflats gave way about 550 million years ago to a carbonate platform (similar to the one around present-day Bahamas), which lasted for the next 300 million years of Paleozoic time. Death Valley's position was then within ten or twenty degrees of the Paleozoic equator. Thick beds of carbonate-rich sediments were periodically interrupted by periods of emergence. Although details of geography varied during this immense interval of time, a north-northeasterly trending coastline generally ran from Arizona up through Utah. The resulting eight formations and one group are 20,000 feet (6 km) thick and underlay much of Cottonwood, Funeral, Grapevine, and Panamint ranges.

In the early- to mid-Mesozoic, the western edge of the North American continent was pushed against the oceanic plate under the Pacific Ocean, creating a subduction zone (place where heavier crust slides below lighter crust). Erupting volcanoes and uplifting mountains were created as a result, and the coastline was pushed over 200 miles (over 300 km) to the west. The Sierran Arc started to form to the northwest from heat and pressure generated from subduction, and compressive forces caused thrust faults to develop.

A long period of uplift and erosion was concurrent with, and followed, the above events, creating a major unconformity. Sediments worn off the Death Valley region were carried both east and west by wind and water. No Jurassic to Eocene-aged sedimentary formations exist in the area except for some possibly Jurassic-age volcanic rock.

Erosion over many millions of years created a relatively featureless plain. Around 35 million years ago sluggish streams migrated laterally over its surface. Several other similar formations were also laid down.

Basin and Range-associated stretching of the crust started around 16 million years ago and had spread to the Death and Panamint valleys area by 3 million years ago (the region is still spreading), creating those valleys by 2 million years before the present. Before this, rocks now in the Panamint Range were on top of rocks that would become the Black Mountains and the Cottonwood Mountains. Lateral and vertical transport of these blocks was accomplished by movement on normal faults. Right-lateral movement along strike-slip faults that run parallel to and at the base of the ranges also helped to develop the area. Torsional forces, probably associated with northwesterly movement of the Pacific Plate along the San Andreas Fault (west of the region), is responsible for the lateral movement.

Igneous activity associated with this stretching occurred from 12 million to 4 million years ago. Sedimentation is concentrated in valleys (basins) from material eroded from adjacent ranges. The amount of sediment deposited has roughly kept up with this subsidence, resulting in retention of more or less the same valley floor elevation over time.

Pleistocene ice ages started 2 million years ago, and melt from alpine glaciers on the nearby Sierra Nevada Mountains fed a series of lakes that filled Death and Panamint valleys and surrounding basins. The lake that filled Death Valley was the last of a chain of lakes fed by the Amargosa and Mojave Rivers, and possibly also the Owens River. About 10,500 years ago the large lake covered much of Death Valley's floor, which geologists call Lake Manly, started to dry-up. Saltpans and playas were created as ice age glaciers retreated, thus drastically reducing the lakes' water source. Only faint shorelines are left.

In 2005, large amounts of flooding resulted in Lake Manly's reappearing on a large scale. Over one hundred square miles were covered by the lake, allowing some tourists and park rangers to become probably the only humans to canoe across the valley. The lake was about two feet at its deepest point. As a result, it evaporated quickly, leaving behind a mud-salt mixture.

Human history

Native Americans

Four known Native American cultures have lived in the area during the last ten thousand years or more. The first known group, the Nevares Spring People, were hunters and gatherers who arrived in the area around 7,000 B.C.E., when lakes were still in Death Valley and neighboring Panamint Valley, remnants of the once huge lakes Manly and Panamint. A much milder climate persisted at that time, and large game animals were still plentiful. By 3,000 B.C.E., the culturally similar Mesquite Flat People displaced the Nevares Spring People. Around two thousand years ago, the Saratoga Spring People moved into the area, which by then was probably a hot, dry desert (the last known lake to exist in Death Valley likely dried up a thousand years before). This culture was more adept at hunting and gathering and was skillful at handcrafts. They also left mysterious stone patterns in the Valley.

A thousand years, later the nomadic Timbisha (formerly called "Shoshone" and also known as "Panamint" or "Koso") moved into the area and hunted game and gathered mesquite beans along with pinyon pine nuts. Because of the wide altitude differential between the valley bottom and the mountain ridges, especially on the west, the Timbisha practiced a vertical migration pattern. Their winter camps were located near water sources in the valley bottoms. As the spring and summer progressed, grasses and other plant food sources ripened at progressively higher altitudes as the weather warmed. November found them at the very top of the mountain ridges where they harvested pine nuts before moving back to the valley bottom for winter. Several families of Timbisha still live within the Park at Furnace Creek (known as Timbisha to the Native peoples). The former village of Maahunu located near Scotty's Castle has been abandoned, although many of the baskets on display at the Castle were made by the Timbisha, who worked there as laborers and housekeepers before the National Park Service took over its care.

Gold-seeking pioneers

The California Gold Rush brought the first non-native Americans known to visit the immediate area. On January 24, 1848, James Marshall and his crew discovered gold at Sutter's Mill in California. This discovery would lure tens of thousands of people from not only the United States but other nations as well. People packed their belongings and began to travel by wagon to what they hoped would be a new and better life. Since the first great influx of these pioneers began in 1849, they are generally referred to as "49ers."

In December 1849, two groups of California Gold Country-bound pioneers with perhaps 100 wagons survived a difficult trek into Death Valley after getting lost on what they thought was a shortcut off the Old Spanish Trail. Known as the Bennett-Arcane Party, they were unable to find a pass out of the Valley for weeks and were forced to slaughter several of their oxen to survive, but were able to find fresh water at the various springs in the area. They used the wood of their wagons to cook the meat and make jerky. The locations of this event is today referred to as "Burned Wagons Camp" and is located near the sand dunes.

After abandoning their wagons, the groups was eventually able to hike out of the Valley through the rugged Wingate Pass. Just after leaving the Valley, one of the women in the group looked back for a final time and said, "Goodbye, Death Valley," a name that has survived to this day. In reality, only one person of the group died in Death Valley, an elderly man named Culverwell. Also included in the party was William Lewis Manly, whose autobiographical book, Death Valley in '49, detailed this trek and greatly popularized the area.

Boom and bust

The ores that are most famously associated with the area were also the easiest to collect (and most profitable): Evaporite deposits such as salts, borate, and talc. Borax was found by Rosie and Aaron Winters near Furnace Creek Ranch (then called Greenland) in 1881. Later that same year, the Eagle Borax Works became Death Valley's first commercial borax operation. William Tell Coleman built the Harmony Borax Works plant and began to process ore in late 1883 or early 1884 until 1888. This mining and smelting company produced borax from which to make soap and for industrial uses. The end product was shipped out of the Valley 165 miles (265 km) to the Mojave railhead in 10-ton-capacity wagons pulled by "twenty mule teams" that were actually teams of 18 mules and 2 horses each. The teams averaged two miles an hour and required about 30 days to complete a round trip. The trade name 20-Mule Team Borax was established by Francis Marion Smith's Pacific Coast Borax Company after Smith acquired Coleman's borax holdings in 1890. A very memorable advertising campaign used the wagon's image to promote the Boraxo brand of granular hand soap and the Death Valley Days radio and television programs. Mining of the ore continued after the collapse of Coleman's empire, and by the 1920s, the area was the world's number one source of borax. Some 6 to 4 million years old, the Furnace Creek Formation is the primary source of borate minerals gathered from Death Valley's playas.

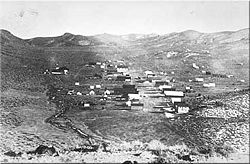

Visitors who arrived later stayed to prospect for and mine deposits of copper, gold, lead, and silver. The remote location and the harsh desert environment hampered these sporadic mining ventures. In December 1903, two men from Ballarat were prospecting for silver. One was an out of work Irish miner named Jack Keane and the other was a Basque butcher named Domingo Etcharren. Keane, quite by accident, discovered an immense ledge of free-milling gold near the duo's work site and named the claim the Keane Wonder Mine. This started a minor and short-lived gold rush into the area. The Keane Wonder Mine along with mines at Rhyolite Nevada, and Skidoo and Harrisburg, California, were the only ones to extract enough metal ore to make them worthwhile. The boomtowns that sprang up around these mines flourished during the first decade of the twentieth century, but soon slowed down after the Panic of 1907.

Early tourism

The first documented tourist facilities in Death Valley were a set of tent houses built in the 1920s, where Stovepipe Wells is now located. People flocked to resorts built around natural springs believed to have curative and restorative properties. In 1927, one of the borax companies working in the Valley turned its Furnace Creek Ranch crew quarters into a resort, creating the Furnace Creek Inn and resort. The spring at Furnace Creek was harnessed to develop the resort, and as the water was diverted, the surrounding marshes and wetlands began to shrink.[2]

Soon, the Valley was a popular winter destination. Other facilities which began as private getaways were later opened to the public. Most notable among these was Death Valley Ranch, better known as Scotty's Castle. This large home built in the Spanish-ranchero style became a hotel in the late 1930s and, largely due to the fame of Death Valley Scotty, a tourist attraction. Death Valley Scotty, whose real name was Walter Scott, was a gold miner who pretended to be the owner of "his castle," which he claimed to have built with profits from his gold mine. Neither claim was true, but the real owner, Chicago millionaire Albert Mussey Johnson, encouraged the myth. When asked by reporters what his connection was to Walter Scott's castle, Johnson replied that he was Mr. Scott's banker.[3]

Protection and later history

President Herbert Hoover proclaimed a national monument in and around Death Valley on February 11, 1933, setting aside almost 2 million acres (8,000 km²) of southeastern California and small parts of westernmost Nevada. Twelve companies worked in Death Valley using Civilian Conservation Corps workers during the Great Depression and into the early 1940s. They built barracks, graded 500 miles (800 km) of roads, installed water and telephone lines, and erected a total of 76 buildings. Trails in the Panamint Range were built to points of scenic interest, and an adobe village, laundry, and trading post were constructed for Shoshone Indians. Five campgrounds, restrooms, an airplane landing field, and picnic facilities were also built.

Creation of the monument resulted in a temporary closing of the lands to prospecting and mining. However, by prior agreement, Death Valley was quickly reopened to mining by Congressional action in June of the same year. As improvements in mining technology allowed lower grades of ore to be processed and new heavy equipment allowed greater amounts of rock to be moved, mining in Death Valley changed. Gone were the days of the "single-blanket, jackass prospector" long associated with the romantic west. Open pit and strip mines scarred the landscape as internationally owned mining corporations bought claims in highly visible locations of the national monument. The public outcry that ensued led to greater protection for all national park and monument areas in the United States.

Congress passed the Mining in the Parks Act in 1976 which closed Death Valley National Monument to the filing of new mining claims, banned open-pit mining and required the National Park Service to examine the validity of tens of thousands of pre-1976 mining claims. Mining was allowed to resume on a limited basis in 1980, with stricter environmental standards. The park's Resources Management Division monitors mining within park boundaries and continues to review the status of 125 unpatented mining claims and 19 patented claim groups, while insuring that federal guidelines are followed and the park's resources are being protected. The only active mining operation in Death Valley National Park in 2003 was the Billie Mine, an underground borax mine located along the road to Dante's View.

Death Valley National Monument was designated a biosphere reserve in 1984. Biosphere reserves are created to promote and demonstrate a balanced relationship between humans and the biosphere. On October 31, 1994, the Monument was expanded 1.3 million acres (5,300 km²) and redesignated a national park by passage of the Desert Protection Act. This made it the largest national park in the contiguous United States.

Many of the larger cities and towns within the boundary of the regional ground water flow system that the park and its plants and animals rely upon are experiencing some of the fastest growth rates of any place in the United States. Notable examples within a 100-mile radius of Death Valley National Park include Las Vegas and Pahrump, Nevada. Between 1985 and 1995, the population of the Las Vegas Valley increased from 550,700 to 1,138,800.[4]

Timbisha names in the Park

- Timbisha, from tümpisa, "rock paint," refers to both the Valley and the village located at the mouth of Furnace Creek. It refers to rich sources of red ochre paint in the Valley.

- Ubehebe Crater, possibly from hüüppi pitsi, "old woman's breast." The Timbisha call it tümpingwosa, "rock basket."

- Wahguyhe Peak, from the Timbisha name waakko'I, "pinyon pine summit." The Timbisha term refers to the entire Grapevine Range.

- Hanaupah Canyon, from the Timbisha name hunuppaa, "canyon springs."

Activities

- Sightseeing by car, four-wheel drive, bicycle, or mountain bike—California State Route 190, the Badwater Road, Scotty's Castle Road, and paved roads to Dante's View and Wildrose provide access to the major scenic viewpoints and historic points of interest. More than 350 miles (560 km) of unpaved and four-wheel drive roads provide access to wilderness hiking, camping, and historical sites.

- Hiking—There are hiking trails of varying lengths and difficulties, but most back country areas are accessible only by cross-country hiking. There are literally thousands of hiking possibilities. The normal season for visiting the park is from October 15 to May 15 due to summer extremes in temperature.

- Camping—There are 10 different designated campgrounds within the park and overnight back country camping permits are available at the Visitor Center. Scotty's Castle is also a popular tourist destination.

- Inns and Resorts—The Furnace Creek Inn and Ranch Resort is a private resort owned and operated by Xanterra Parks & Resorts. The resort is comprised of two separate and distinct hotels, the Furnace Creek Inn, is a four star historic hotel. The Furnace Creek Ranch is a three star ranch style property reminiscent of the mining and prospecting days. Xanterra also operates the Stovepipe Wells Village motel, located 25 miles north of Furnace Creek. The Furnace Creek Inn and Ranch and the Stovepipe Wells Village are the only three inns located inside the Death Valley proper. There are a few motels near various entrances to the park, in Shoshone, Death Valley Junction, and Panamint Springs.

- The Visitor Center—Located in the Furnace Creek resort area on California State Route 190, presents a 12-minute-long introductory slide program, which is shown every 30 minutes. During the winter season, November through April, rangers present a wide variety of walks, talks, and slide presentations about Death Valley cultural and natural history. The center has informational displays about the geology, climate, wildlife, and natural history of the park. There is also an area focused on the human history and pioneer experience. There is a fully staffed information desk with information on all aspects of the park and its operation. The Death Valley Natural History Association offers books for sale specifically geared towards the natural and cultural history of the park.

- Stargazing—Death Valley National Park has the darkest night sky of all U.S. National Parks and one of the darkest in the United States, so it is a popular area for stargazing.

Notes

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey, Death Valley geology field trip. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey, Furnace Creek: Focus on Water. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ↑ National Park Service, Scotty's Castle - Behind the Scenes Continues. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey, Death Valley geology field trip. Retrieved July 23, 2007.

Sources and Futher Reading

- Harris, Ann G., Esther Tuttle, and Sherwood D. Tuttle. Geology of National Parks. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Pub. Co., 1990. ISBN 0840346190

- Kiver, Eugene P., David V. Harris, and David V. Harris. Geology of U.S. Parklands. New York: J. Wiley, 1999. ISBN 0471332186

- National Park Service. The Civilian Conservation Corps. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- Sharp, Robert P., and Allen F. Glazner. Geology Underfoot in Death Valley and Owens Valley. Missoula, Mont: Mountain Press Pub., 1997. ISBN 0878423621

- Wiki Travel. Death Valley National Park. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

External links

All links retrieved July 26, 2022.

- National Park Service. Death Valley.

- The American Southwest California. Death Valley National Park.

| National parks of the United States | |

|---|---|

| Acadia • American Samoa • Arches • Badlands • Big Bend • Biscayne • Black Canyon of the Gunnison • Bryce Canyon • Canyonlands • Capitol Reef • Carlsbad Caverns • Channel Islands • Congaree • Crater Lake • Cuyahoga Valley • Death Valley • Denali • Dry Tortugas • Everglades • Gates of the Arctic • Glacier • Glacier Bay • Grand Canyon • Grand Teton • Great Basin • Great Sand Dunes • Great Smoky Mountains • Guadalupe Mountains • Haleakala • Hawaii Volcanoes • Hot Springs • Isle Royale • Joshua Tree • Katmai • Kenai Fjords • Kings Canyon • Kobuk Valley • Lake Clark • Lassen Volcanic • Mammoth Cave • Mesa Verde • Mount Rainier • North Cascades • Olympic • Petrified Forest • Redwood • Rocky Mountain • Saguaro • Sequoia • Shenandoah • Theodore Roosevelt • Virgin Islands • Voyageurs • Wind Cave • Wrangell-St. Elias • Yellowstone • Yosemite • Zion List by: date established, state |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 01:44:55 | 27 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Death_Valley_National_Park | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF