Jesus Of Nazareth

From Nwe

From Nwe Jesus Christ, also known as Jesus of Nazareth or simply Jesus, is Christianity's central figure, both as Messiah and, for most Christians, as God incarnate. Muslims regard him as a major prophet and some regard him as the Messiah. Many Hindus also recognize him as a manifestation of the divine (as do Bahá'í believers), while some Buddhists identify him as a Bodhisattva. For Christians, Jesus' example, teaching, death and resurrection are inspirational of a life of service to others, of love-in-action. More than that, the person of Jesus represents God's revelation to humanity, making possible communion with God.

As might be expected with a man of this stature, partial understandings, and total misunderstandings of his life and mission abound. Jesus has been described as a peacemaker, as a militant zealot, as a feminist, as a magician, as a homosexual, as a married man with a family and a political agenda, as a capitalist, as a social activist and as uninterested in social issues, as offering spiritual salvation in another realm of existence and as offering justice and peace in this world.

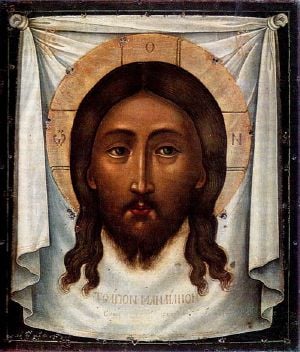

Did he intend to establish a new religion, or was he a faithful Jew? Many Europeans have depicted him with Gentile features, light-skinned and with blue eyes. Departing entirely from the Biblical record, some Asians have speculated that he visited India and was influenced by Buddhism. Traditional belief is that Jesus lived in Palestine his entire life, except for a few childhood years in Egypt.

Learning of the real Jesus from amidst the cacophony of interpretations is a major critical task. That it is so challenging to uncover the real Jesus might be a blessing in disguise, forcing the serious minded to seek in humility and sincere prayer and surrender (as did Albert Schweitzer, who left the career of a critical scholar for that of a medical missionary in Africa). This approach may take the form of making a living spiritual relationship with Jesus—as Lord and Savior, or a teacher of wisdom, an exemplary life to follow, or a spiritual friend and guide. Above all, Jesus was the "man of sorrows" who, despite a most difficult life, never closed his heart and never ceased to love. Knowing Jesus in any of these ways may help us to value the spiritual dimension of life, to accept that God has a greater purpose for human life and for the world of his creation. Jesus invites us to follow him on a spiritual path in which serving God is manifest by giving of self and living for the sake of others.

The Historical Jesus

Until the late eighteenth century, few Christians doubted that the Jesus in whom they believed and the Jesus of history were identical. In 1778, a book by Hermann Samuel Reimarus (1694-1768) was posthumously published which ended this comfortable assumption. This launched what became known as the “Quest of the Historical Jesus.” Reimarus argued that the gospels contain a great deal of fabricated material that expressed the beliefs of the church, not historical fact. He sliced huge portions of text from the gospels, suggesting that angelic visits, miracles, Jesus' resurrection and ascension were all fabrications. Many incidents were borrowed from the Hebrew Bible, such as the slaughter of the innocents by Herod, to stress that Jesus had a lot in common with Moses. His forty-day temptation was to emulate Moses' various period of forty years. His feeding of crowds was to emulate Elijah. Reimarus points out, as do numerous others, that the disciples did not witness the main events of Jesus’ trial and execution, or the resurrection.

The issues that Reimarus opened for debate remain the bread and butter of Jesus studies and of theological discussion. Did Jesus think of himself as the Messiah? Did he have any self-awareness of his divinity, or divine son-ship? Or did he consider himself simply a human being, like any other? Scholars also debate about whether Jesus preached a spiritual or a worldly message. Was he concerned about peace, justice, equality and freedom in this world, or about salvation from sin for a life in paradise after death? Was Jesus an apocalyptic preacher who believed that the end was near? Or was he a wisdom teacher giving truths for living in the present? It is no easy task to decide these questions, as features of the gospels support a variety of interpretations.

As to his life, scholarly consensus generally accepts that Jesus was probably born in Nazareth, not Bethlehem, that he did not perform miracles (although he may have had some knowledge of healing), and that the resurrection was not a physical event but expresses the disciples’ conviction that Jesus was still with them even though he had died.

In the Jesus Seminar, members used various techniques to authenticate Jesus' words, such as characteristic style of speech, what fits the context of a Jesus who was really a good Jew and who did not regard himself as divine, and what reflects later Christian theology. In its work, the members of the Jesus Seminar voted on whether they thought a verse was authentic or not. John's gospel attracted no positive votes. Many Christians regard Jesus as a pacifist, but the work of Horsley, among others, questions this, suggesting that Jesus did not reject violence.

Sources for Jesus Life

The primary sources about Jesus are the four canonical gospel accounts, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Jesus spoke Aramaic and perhaps some Hebrew, while the gospels are written in koine (common) Greek. Dating of these texts is much debated but ranges from 70 C.E. for Mark to 110 C.E. for John—all at least 40 years after Jesus' death. The earliest New Testament texts which refer to Jesus are Saint Paul's letters, usually dated from the mid-first century, but Paul never met Jesus in person; he only saw him in visions. Many modern scholars hold that the stories and sayings in the gospels were initially handed down by oral tradition within the small communities of Christian believers, then written down decades later. Hence, they may mix genuine recollections of Jesus' life with post-Easter theological reflections of Jesus' significance to the church.

The first three gospels are known as the synoptic gospels because they follow the same basic narrative. If Mark was the earliest (as many scholars contend), Matthew and Luke probably had access to Mark, although a minority of scholars consider that Matthew was the earlier. Each writer added some additional material derived from their own sources. Many scholars believe that Matthew and Luke may have used a long-lost text called ‘Q’ (Quelle) while John may have used a “signs gospel.” These were not chronological narratives but contained Jesus sayings and signs (miracles) respectively. The Gospel of John has a different order. It features no account of Jesus' baptism and temptation, and three visits to Jerusalem rather than one. Considered less historically reliable than the synoptic gospels with its longer, more theological speeches, John's treatment of the last days of Jesus is, however, widely thought to be the more probable account.

In addition to the four gospels, a dozen or so non-canonical texts also exist. Among them, the Gospel of Thomas is believed by some critics to predate the gospels and to be at least as reliable as they are in reporting what Jesus said. However, the Gospel of Thomas was preserved by a Gnostic community and may well be colored by its heterodox beliefs.

Also considered important by some scholars are several apocryphal writings such as the Gospel of the Hebrews, the Gospel of Mary, the Infancy Gospels, the Gospel of Peter, the Unknown Berlin Gospel, the Naassene Fragment, the Secret Gospel of Mark, the Egerton Gospel, the Oxyrhynchus Gospels, the Fayyum Fragment and some others compiled in The Complete Gospels.[1] The status of the Secret Gospel of Mark, championed by Morton Smith[2] has been challenged.[3] The authenticity of the recently published Gospel of Judas[4] is contested, however it adds no new historical or biographical data. Finally, some point to Indian sources, such as the Bahavishyat Maha Purana.[5] This is said to date from 115 C.E. Traditional Christian theologians doubt the reliability of this extra-biblical material.

Much popular and some scholarly literature also uses the Qumran Community's Dead Sea Scrolls, discovered in a cave by the Dead Sea in 1946 or 1947 to interpret the life of Jesus. These documents shed light on what some Jews believed at roughly Jesus' time, and suggest that Jesus shared some ideas in common with the Qumran community and with the Essenes, but many agree with the Jesus Seminar's conclusion that the scrolls "do not help us directly with the Greek text of the gospels, since they were created prior to the appearance of Jesus."[6] Josephus's (d. 100 C.E.) much-debated Testimonium Flavinium[7]is late, if authentic, as is the brief mention of Christ in Tacitus's Annals (d. 117 C.E.).

Chronology

There is a great deal of discussion about the dating of Jesus’ life. The canonical gospels focus on Jesus' last one to three years, especially the last week before his crucifixion, which, based upon mention of Pilate, would have been anywhere from the years 26 to 36 in the current era. The earlier dating agrees with Tertullian (d. 230) who, in Adversus Marcion XV, expresses a Roman tradition that placed the crucifixion in the twelfth year of Tiberius Caesar. A faulty sixth century attempt to calculate the year of his birth (which according to recent estimates could have been from 8 B.C.E. to 4 B.C.E. became the basis for the Anno Domini system of reckoning years (and also the chronologically-equivalent Common Era system).

The choosing of December 25 as his birthday was almost certainly because it corresponded with the existing winter solstice, and with various divine birthday festivals. The Eastern Church observes Christmas on January 6. Clement of Alexandria (d. 215) suggested May 20.

The Gospel of John depicts the crucifixion just before the Passover festival on Friday, 14 Nisan, whereas the synoptic gospels describe the Last Supper, immediately before Jesus' arrest, as the Passover meal on Friday, 15 Nisan. The Jews followed a mixed lunar-solar calendar, complicating calculations of any exact date in a solar calendar.

According to John P. Meier's A Marginal Jew, allowing for the time of the procuratorship of Pontius Pilate and the dates of the Passover in those years, his death can be placed most probably on April 7, 30 C.E. or April 3, 33 C.E. or March 30, 36 C.E.

Some scholars, notably Hayyim Maccoby, have pointed out that several details of the triumphant entry into Jerusalem—the waving of palm fronds, the Hosanna cry, the proclamation of a king—are connected with the Festival of Sukkot or Tabernacles, not with Passover. It is possible that the entry (and subsequent events, including the crucifixion and resurrection) in historical reality took place at this time—the month of Tishri in autumn, not Nisan in spring. There could have been confusion due to a misunderstanding, or a deliberate change due to doctrinal points.

A Biography

Birth and Childhood

The traditional account of Jesus' life is that he was born at the beginning of the millennium, when Herod the Great was king. His birth took place in Bethlehem during a census and was marked by special signs and visitations. His mother, Mary, became pregnant without any sexual contact with her husband, Joseph (Matt. 1:20, 25). Jesus' birth had been announced to her by an angel. News that a king of the Jews had been born who was of the lineage of David reached Herod, who ordered the execution of all newborn male babies. Some recognized Jesus as the one who had been promised, who would bring salvation to the world (Luke 2:25-42). Matthew often cites Hebrew Bible passages, saying that they have been fulfilled in Jesus. Angelic warning enabled Joseph, Mary, and Jesus to flee to Egypt, where they remained for an unspecified period. They later returned to Nazareth in Galilee, their hometown (Matt. 2:23). At age 12, Jesus visited the Temple of Jerusalem (Luke 2:39-52), where he confounded the teachers with his wisdom. He spoke of “doing his Father's business.”

Several difficulties beset this account, beginning with the virgin birth. The notion of human parthenogenesis is scientifically implausible and ranks as perhaps the greatest miracle surrounding his life. It is commonplace for Christian believers to accept this claim at face value—especially given its theological import that Jesus was literally the "son" of God (compare pagan stories of heroes being fathered by Zeus coupling with mortal women). For those seeking a naturalistic explanation, candidates for his human father include the priest Zechariah, in whose house Mary lived for three months before her pregnancy became known (Luke 1:40, 56).

Yet the mere fact that the gospels proclaimed the virgin birth suggests that there were widespread rumors that Jesus was an illegitimate child—attested to by Mark 6:3 where his neighbors call him the "son of Mary"—not the son of Joseph. There is even a Jewish tradition asserts that he was fathered by a Roman soldier. These rumors undoubtedly caused many problems for Jesus and for Mary. The relationship between Mary and Joseph may have suffered, and as they had more children for whom parentage was not at issue, Jesus became an outcast even in his own home. As Jesus remarked, "A prophet is not without honor, except... in his own house" (Mark 6:4).

The above mentioned story of Jesus teaching in the Temple also hints at the strain between Jesus and his parents. His parents brought the boy to Jerusalem, but on the return trip they left him behind and did not know he was missing for an entire day. When they later found him, instead of apologizing for their neglect they upbraided Jesus for mistreating them (Luke 2:48).

Remembrance of the controversy surrounding Jesus’ birth appears in the Qur'an, where Jesus’ first miracle was when, although only a few days old, he spoke and defended his mother against accusations of adultery (Qur'an 19:27-33). As a boy, he made a bird fly (3:49 and 5:109-110). According to the Infancy Gospel of Thomas these childhood miracles caused great friction between Jesus' family and the other villagers. He must have suffered great loneliness.[8] The prophetic verses of Isaiah hint at the suffering of his childhood: "He grew up... like a root out of dry ground; he had no form or comeliness that we should look at him, and no beauty that we should desire him" (Isa. 53:2).

In those days it was customary for Jewish males to marry around age 18 to 20, with the match arranged by the parents. Yet Jesus did not marry—a very unusual situation in the society of his day. Did Jesus refuse to permit his mother to find him a wife for providential reasons? Or did his stained reputation make it difficult for his mother to find a suitable mate for him? At the marriage at Cana, when his mother asked Jesus to turn water into wine, he replied in anger, "O woman, what have you to do with me?" (John 2:4). Was he reproaching his mother for wanting him to help with the marriage of another when she did not provide him with the marriage he desired?

Jesus and John the Baptist

Jesus had a cousin, John. He started to preach, calling for people to prepare themselves for the coming of he who would judge and restore Israel (Luke 3:7-9). He baptized many as a sign that they were ready for the "Lord." When Jesus was 30 years of age, he accepted baptism from John at the Jordan River. A heavenly voice proclaimed that Jesus was God's “beloved son” (Mark 1:1-9). John then testified to Jesus (John 1:32-34).

John is traditionally honored on account of this testimony, yet evidence points to only half-hearted support for Jesus. There is no record that John ever cooperated with Jesus, and they seem to have founded rival groups. Quarrels broke out between John's disciples and Jesus' disciples (John 3:25-26), and while John obliquely praised his greatness, he kept his distance: "He must increase, but I must decrease" (John 3:30). John went his own way and ended up in prison, where he voiced his doubts, "Are you he who is to come, or shall we look for another?" (Matt. 11:3). Jesus answered in disappointment, "Blessed is he who takes no offense at me" (Matt. 11:6). The Baptist movement remained a separate sect, continuing on after John's death. A small population of Mandaeans exists to this day; they regard Jesus as an impostor and opponent of the good prophet John the Baptist—whom they nonetheless believe to have baptized him.

According to Matthew's account, Jesus had assigned a role to John, that of Elijah the prophet, whose return Jews believed was to presage the Messiah (Matt. 11:14). The absence of Elijah was an obstacle to belief in Jesus (Matt. 17:10-13). John the Baptist was highly thought of by the Jewish leadership of his day. It must have disappointed Jesus greatly when John did not accept that role—he even denied it (John 1:21)—because it made his acceptance by the religious leaders of his day that much more difficult.

Jesus may have sought to overcome this setback by taking the role of the second coming of Elijah on himself, not least by performing miracles similar to what Elijah had done. Apparently this impression of Jesus was believed by some of his contemporaries—that he was the return of Elijah (Mark 6:14-16; Matt. 14:2).

Public Ministry

After this, Jesus spent forty days fasting and praying in the wilderness, where he was tempted by Satan to use his gifts to serve himself, not others, and to gain worldly power. He completed this difficult condition victoriously. On that foundation, he began his ministry.

Some of his early preaching sounded a lot like John the Baptist: God's kingdom was at hand, so people should repent of their sins. Then, entering the synagogue in Nazareth, he read from Isaiah 61:17-25 to proclaim his role as the messiah—the word in Hebrew means "anointed one":

The spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because he has anointed me to preach good news to the poor.

He has sent me to proclaim release of the captives

and recovering of sight to the blind,

and to set at liberty those who are oppressed,to proclaim the acceptable year of the Lord. (Luke 4:18-19).

Many regard the Sermon on the Mount (Matt. 5:1-7:27) as a summary of Jesus' teaching:

- "Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth."

- "Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God."

- "Anyone who looks at a woman lustfully has already committed adultery with her in his heart."

- "If anyone strikes you on the right cheek, turn to him the other also."

- "Love your enemies, and pray for those who persecute you."

- "Do not be anxious about your life... but seek first God's kingdom and his righteousness."

- "Why do you see the speck in your brother's eye when you do not notice the log that is in your own eye?"

- "Enter by the narrow gate."

Jesus and His Disciples

Jesus chose 12 men to be his disciples, who appear to have spent most of the time in his company. He instructed them to sell what they had and give to the poor (Luke 12:33). He sent them out to preach from town to town (Matt. 10:5-15). When they gave feasts, they should invite the poor and the sick and the blind, not the great and the good (Luke 14:13). Jesus loved his disciples and shared their sorrows (John 11:32-36). He also tried to educate them, yet they were simple people not schooled in religion. He may have been disappointed to have to work with such, according to the Parable of the Banquet, in which all the invited guests find excuses not to come, leaving the master to beat the bushes to bring in the blind and the lame (Luke 14:16-24). They did not fully grasp his teachings, as when James and John asked whether they would sit on thrones (Mark 10:37). Jesus even suggests that he had truths he could not reveal because his disciples were not ready to receive them (John 16:12).

Jesus himself lived simply, accepting hospitality when it was offered. He was critical of wealth accumulation and of luxurious living, of storing up treasure on earth (Matt. 6:19-24). He enjoyed eating meals with the despised and rejected, challenging social and religious conventions, for which he was criticized (Mark 2:16; Matt. 9:11).

According to the gospels, Jesus healed and fed people. He exorcised demons. Once he walked on water. He also calmed a storm. He was especially sympathetic towards lepers. Yet while his miracles drew large crowds, they were not conducive to real faith. When he stopped performing them, the people melted away, leaving him alone with his few disciples (John 6).

He often spoke about the availability of “new life.” He invited people to be reborn spiritually, to become childlike again (Mark 10:15; John 3:3). Sometimes, he forgave sins (Mark 2:9). Once, he went to pray on a mountain top with three disciples, where Moses and Elijah appeared alongside him. This is known as the Transfiguration, because Jesus appeared to “glow with a supernatural glory.”[9]

Peter, who was Jesus' chief disciple, confessed that he believed Jesus was the Messiah, the "Son of the Living God" (Matt. 16:16). The Messiah was the God-sent servant or leader whom many Jews expected would deliver them from Roman rule and reestablish the Davidic kingdom, restoring peace and justice. Jesus, though, told Peter and the other disciples not to tell anyone about this, which was later dubbed the “Messianic secret.”

Growing Opposition

Shortly after these events, Jesus starts to travel towards Jerusalem and also speaks of the necessity of his own death; of being rejected like the prophets, even of the chief priests delivering him up to die (Mark 10:33-34). Jerusalem, he said, would be surrounded by enemies and destroyed (Luke 21:6-8; Mark 13:2) which sounded threatening. He is depicted as at odds with the religious leaders, who started to plot against him. They also tried to trick him in debate (Mark 8:11; 10:2; 11:18; 12:3). They accused him of making himself God (John 10:33). Perhaps with the suffering servant of Isaiah 53 in mind, Jesus said that before the “restoration,” he would have to suffer and be humiliated (Mark 9:12).

As he drew closer to Jerusalem, his popularity with the common people increased—but so did opposition from the religious leaders. Jesus' charismatic preaching—his teaching that people could have direct access to God—bypassed the Temple and the trained, official religious leaders. They challenged Jesus, asking on what or whose authority he did and said what he did (Matt. 21:23). Jesus had no Rabbinical training (John 7:14). He accused the religious leaders of loving the praise of people instead of God (John 12:43) and of rank hypocrisy, of being blind guides more fond of gold than of piety (Matt. 23), especially targeting the Pharisees.

Yet many scholars note similarities between Jesus and the Pharisees, who were the direct ancestors of rabbinic Judaism. Jesus, these writers point out, had a lot in common with Hillel and Honi the Circle Drawer, who are honored as Jewish sages in rabbinic literature. The Pharisees, like Jesus, were interested in inner piety; it was the Saducees, who controlled the Temple, who were interested in ritual observance. Jesus' criticisms in Matthew 23 make more sense if directed at the Saducees.

Those who stress common ground between Jesus and the Pharisees suggest that passages referring to Jews as plotting to kill him or as trying to trick him—and Jesus' criticism of them—were back-projected by a later generation of Christians to reflect their own estrangement from and hostility towards Judaism. Also, this deflected blame away from the Roman authorities, whom Christians wanted to appease. The scene where Pontius Pilate washed his hands would also be back projection.

Some posit that the gospels reflect a struggle between Jewish Christians, such as Peter and James, and the Paul-led Gentile Church. The Pauline victory saw an anti-Jewish and pro-Roman bias written into the gospel record (see Goulder 1995). It was also Paul who imported pagan ideas of sacrificial death for sin and dying and rising saviors into Christian thought. Some depict Jesus as a rabbi.[10] Some suggest that Jesus, if he was a rabbi, probably married.[6][11]

The Women in Jesus' Life

Women also belonged to Jesus' inner circle, spending much time with him (John 11:1-4). Jesus "loved Martha and her sister, Mary" and their brother Lazarus. He brought Lazarus back to life. He regarded this circle of disciples, including the women, as his spiritual family: "Whoever does God's will is my brother and sister and mother" (Mark 3:35). Elizabeth S. Fiorenza stresses that Jesus affirmed the feminine and that Sophia (wisdom) was feminine—despite its later neglect by the church.[12] Jesus was inclusive. He honored women's leadership together with that of men.

Among the women in Jesus' life, Mary Magdalene stands out. There have been many attempts, both scholarly and fictional, to elucidate her identity and importance.[13] According to Mark 14:3-9, when Jesus was at Bethany, two days before the Last Supper, a woman anointed Jesus with costly ointment. John recounts the same story (John 12:1-8) and identifies the woman as Mary Magdalene. Judas Iscariot took offense at her extravagant devotion; it is the final insult that caused him to go to the priests to betray Jesus. At the resurrection, Mary was the first disciple to meet the resurrected Jesus, whom she wished to embrace (John 20:17); but he forbade it. In the Gnostic Gospel of Mary, she appeared not only as the most devoted disciple, but as one to whom Jesus entrusted hidden wisdom beyond what he taught the male disciples.

What was the nature of Mary's relationship with Jesus? When Mary was anointing Jesus with oil, did Judas take offense only because of the extravagance, or was he jealous? (The conventional motivation for Judas' betrayal, over money, is unsatisfying considering that Judas was entrusted as the treasurer of Jesus' circle). Yet the gospels make no mention of Jesus having any sexual relations, or of marriage. Most Christians believe that Jesus was celibate.

Nevertheless, there is a genre of blood-line literature, for whom Jesus and Mary Magdalene established a lineage whose true identity has been protected by secret societies, such as the Knights Templar. The legendary Holy Grail refers not to the cup used by Jesus at the Last Supper but to Jesus' blood line.[14] Dan Brown's novel The Da Vinci Code transforms this into fiction, linking the concealment of Jesus' marriage and offspring with the suppression of the sacred feminine by a male-dominated Roman church.[15] Jesus did not teach a spirituality that is best achieved by celibate withdrawal from the world but within the midst of life. Sexuality is not evil or dangerous—the devil's gateway to the soul—but sacred and holy.

The Kingdom of God

Jesus characteristically spoke in parables—earthly stories using metaphors drawn from daily life—often from agriculture and fishery with an inner spiritual meaning. He also used paradox. Most of all, he spoke about life in the Kingdom of God. He called God Abba (“Father”) and spoke of enjoying an intimate relationship with him (see John 13:10). Yet the dawning Kingdom of God also would bring about great social changes, in line with Jewish belief. The humble, he said, would be exalted and the proud brought low (Luke 18:14).

He seems to have referred to himself as the “Son of Man,” for example, saying, “foxes have holes, birds have nests, but the Son of Man has nowhere to lay his head” (Matt. 8:19). Several passages refer to the Son of Man coming “on a cloud with power and great glory” (Luke 21:27); others to signs of the End of Days when the Son of Man will come, although “of that day and hour no man knows” (Matt. 25:36). His end vision includes judgment between the nations (Matt. 25:32)—those who fed the hungry, visited the sick, and clothed the naked will be rewarded; those who did not will be punished.

Scholars have long debated what the content was of the Kingdom of God that Jesus preached. Most Christians are accustomed to thinking that he spoke of a spiritual kingdom that is "not of this world" (John 18:36). In the nineteenth century, Reimarus opened up the debate by suggesting that Jesus was preaching of an earthly kingdom, that he was concerned about peace, justice, equality and freedom in this world, more than about salvation from sin for a life in paradise after death. He presumed that Jesus thought himself the Messiah, but suggests that he failed in his mission, because he did not establish an earthly kingdom.

Miller, who surveys this debate, asks whether Jesus was or was not an apocalyptic preacher.[16] That is, did he think that the end was near? Reimarus placed eschatology at the center of discussion. Liberal scholars, most notably Albrecht Ritschl (1822-89) represented Jesus as a teacher of eternal truths, as a source of moral and ethical guidance. This stresses imitating Jesus, helping others, feeding the hungry, clothing the naked (Luke 6:46) more than believing in Jesus. Yet Ritschl's son-in-law, Johannes Weiss (1863-1914) proposed the antithesis that Jesus had been an apocalyptic preacher who thought the world as we know it would soon end.

Albert Schweitzer developed this thesis in his classic Quest of the Historical Jesus (English translation, 1910). He said that the liberals merely dressed Jesus in their own clothes. The real Jesus, he said, remains alien and exotic, so much a product of his eschatological worldview, which we do not share, that he escapes us—constantly retreating back into his own time.[17] Jesus believed that his death on the cross, based on his understanding of himself as suffering Messiah, would usher in the Kingdom. This did not happen. In a sense, then, Jesus failed; yet from his example people can gain inspiration towards a life of self-sacrifice and love of others. We can, said Schweitzer, still respond to Jesus call to follow him. Although we can know little for certain about Jesus, a spirit flows from him to us calling us to existential sacrifice and service.

In the twentieth century, the work of Marcus Borg, Dominic Crossan, and the Jesus Seminar resurrected the idea that Jesus taught as sapiential, or here-and-now kingdom (see John 17:20-21). Others, like E.P. Sanders, have kept to the position that Jesus was an apocalyptic preacher. The picture of Israelite society that is now known from the Dead Sea Scrolls indicates that many Jews did expect a messiah, or even several messiahs, who would liberate them from Rome. Certainly this was the faith of the community at Qumran, and some scrolls scholars put John the Baptist in touch with them.

The Passion

The events surrounding Jesus' last days—his death and resurrection—are called the Passion. Since it is generally believed that Jesus brought salvation through his atoning death on the cross, Jesus' Passion is the focus of Christian devotion more than his earthly ministry.

The Last Supper

After approximately three years of teaching, at the age of 33, Jesus entered Jerusalem. He did so dramatically, riding on a donkey (Matt 21:9) while the crowd that gathered shouted, “Hosanna to the Son of David,” which, according to Bennett, “looks very much like a public disclosure of Jesus’ identity as the Davidic Messiah [and] gives the impression that he was about to claim kingly authority.”[18]

Judas Iscariot, one of the 12 disciples, agreed to betray Jesus to the authorities, whom Jesus continued to annoy by storming into the Temple and up-turning the money changers' tables (Matt 21:12; John has this incident earlier in Jesus' career, John 3:15).

Apparently aware that he was about to die, Jesus gathered his disciples together for what he said would be his last meal with them before he had entered his father's kingdom (Matt. 26:29). Following the format of a Shabbat meal, with a blessing over bread and wine, Jesus introduced new words, saying that the bread and wine were his “body” and “blood,” and that the disciples should eat and drink in remembrance of him. The cup, he said, was the “cup of the new covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins” (Matt. 26:26-28).

Traditionally, this took place close to the Jewish Passover. Reference here to a new covenant evoked memories of Jeremiah 31:31: “behold I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and with the house of Judah, I will put my law in their hearts and will be their God.” Jesus had spoken about a new relationship with God, and John's gospel, in its theological prologue, speaks of the law as being “given by Moses,” but of Jesus' bringing “grace and truth” (John 1:17). Salvation is not achieved by obeying the law but by faith in Jesus: “whosoever believes on him shall not perish” (3:16).

Betrayal and Trial

Following this event, Jesus retreated to a garden outside Jerusalem's walls to pray, asking that if God wills, the bitter cup of his impending death might be taken from him. Yet at the end of his prayer he affirms his obedience to destiny: "Nevertheless not my will, but thine, be done" (Luke 22:42). While praying, Judas appeared accompanied by soldiers. Judas identified Jesus for the soldiers by kissing him (on both cheeks, in the Middle Eastern fashion), and they arrested him.

His trial followed. Jesus was tried before the high priest, accused of blasphemy. Jesus was also tried before Herod Antipas, because his jurisdiction included Galilee and before the Roman governor, Pilate, who alone had the authority to pronounce a death sentence. Pilate hesitated. Jesus was causing public disturbance, but Pilate's wife intervened, calling Jesus a “righteous man.” The charge before Pilate was treason—that Jesus claimed to be king of the Jews. The public or key figures in the local leadership were now demanding his death. Pilate, remembering a custom that allowed him to release one prisoner at Passover, offered those gathered the choice for the release of Jesus or a prisoner called Barabbas. They chose Barabbas.

The Crucifixion

Pilate poured water over his hand, saying that he was innocent of Jesus' blood. However, he allowed him to be crucified. Jesus, who had already been whipped mercilessly, was now forced to carry his own cross to the place of execution outside the city. When he stumbled, Simon the Cyrene, a passerby, was conscripted to help him. Two other criminals were crucified on either side of Jesus on the same hillock. Of his supporters, only his mother and one other disciple appear to have witnessed the crucifixion (John 19:26).

Peter, as Jesus had predicted, denied even knowing Jesus. Jesus' side was pierced while he hung on the cross, and he was given vinegar to drink when he complained of thirst. Jesus spoke words of forgiveness from the cross, praying for the soldiers who were mocking him, tormenting him, and taking even his clothes, and then declared, “it is finished” just before he expired. His body was taken down and placed in a guarded tomb, against the possibility that his disciples might steal it so that words he had spoken about rising after three days would apparently come true (see Mark 10:31).

Muslims believe that Jesus was neither killed nor crucified, but God made it appear so to his enemies (Qur'an 4:157). Some Muslim scholars maintain that Jesus was indeed put up on the cross, but was taken down and revived. Others say that someone else, perhaps Judas, was substituted for Jesus unbeknownst to the Romans. Their belief is based on the Islamic doctrine that the almighty God always protects his prophets—and Jesus was a prophet. However, the Christian understanding of the crucifixion points to the unparalleled love that Jesus showed in sacrificing his life: "Greater love has no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends" (John 15:13).

Outwardly, Jesus' crucifixion appeared no different from the execution of a common criminal (crucifixion being the Roman form of execution in those days). But inwardly, it was Jesus' heart as he went to the cross that made it a sacred and salvific act. From the moment Jesus set his course to go to Jerusalem, he knew it would lead to his death. When Peter tried to stop him, he rebuked him saying, "Get behind me, Satan!" (Matt. 16:21-23) because to stop him would be to hinder God's plan for salvation. Jesus went to his death as a voluntary act of self-sacrifice, to redeem the sins of all humanity, as the prophet Isaiah taught:

He was wounded for our transgressions,

he was bruised for our iniquities;

upon him was the chastisement that made us whole,

and with his stripes we are healed.

All we like sheep have gone astray;

we have turned everyone to his own way;

and the Lord has laid on himthe iniquity of us all. (Isa. 53:6-7)

Jesus did not offer any resistance. When he was about to be arrested, one of his followers took a sword and struck one of the arresting party, but Jesus told him to put his sword away, "for all who take the sword will perish by the sword" (Matt. 26:52). On the cross, as he was about to expire, he demonstrated ultimate in forgiveness, saying to the soldiers, "Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do" (Luke 23:34). To the very end, he practiced loving his enemies. This unshakable love was Jesus' true glory.

The Resurrection

The next morning (Sunday), a group of women went to embalm Jesus' body but instead saw that the stone had been rolled away and that the tomb, apart from Jesus' grave clothes, was empty. Mary Magdalene remained behind, and it was to her that Jesus first appeared. She ran to embrace him, but Jesus told her not to touch him but rather to go and spread the news to the other disciples (John 20:11-18).

A series of encounters between Jesus and his disciples followed. On the road to Emmaus, the resurrected Jesus net two disciples who were despondent over his death. They had lost hope, believing that Jesus "was the one to redeem Israel" (Luke 24:21). Jesus proceeded to explain from the scriptures the significance of his suffering and death, and then shared a meal with them, at which point they recognized who he was. In another scene he permitted the doubting disciple Thomas to physically touch him (John 20:26-29). Finally, Jesus said farewell—telling them to wait in Jerusalem until the Holy Spirit comes upon them, commanding them to tell all people what he had taught and to baptize them in the name of the Father, the Son and the Spirit. Then he ascended into heaven (Matt. 28:16-20; Luke 24:49-53).

Jesus' resurrection was the signal event in Christianity. It was Jesus' triumph over death and proof that he is the Christ—the Son of God. It also signaled that by abiding in Christ, believers can likewise triumph over death, and overcome any painful and difficult situation. No oppressor or earthly power can defeat the power of God's love manifest in Christ. The resurrection of the crucified Christ overturned all the conventional calculations of power and expediency. As Paul wrote,

We preach Christ crucified, a stumbling-block to Jews and folly to Gentiles, but to those who are called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ is the power of God and the wisdom of God... for the weakness of God is stronger than men. (1 Corinthians 1:23-25)

Pentecost: The Birth of the Church

Fifty days later, at Pentecost, while the disciples waited in an upper room, the Spirit descends onto them:

And suddenly there was a sound from heaven, as of a rushing mighty wind, and it filled all the house where they were sitting. And there appeared unto them cloven tongues like as of fire, and it sat upon each of them. And they were all filled with the Holy Ghost, and began to speak with other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance. (Acts 2:1-4)

Peter's speech to the multitude, which followed, establishes the kerygma (proclamation, or basic message) of what the primitive church believed about Jesus; he had been approved of God by miracles and signs, he had been crucified by wicked men but had risen in glory. Jesus is alive and seated at God's right hand, as both Lord and Messiah. Those who believe in his name, and accept baptism, will be cleansed of all sins and receive the Holy Spirit (Acts 2:37-38).

Christians also believe that Jesus will return to earth before the Day of Judgment. The doctrine of the Second Coming attests to the unfinished quality of Jesus work, where salvation and the Kingdom are spiritually present but yet to be manifest in their fullness—in the fullness of time.

Who Was Jesus?

Scholarly views

Scholars such as Howard Marshall, Bruce Metzger and Thomas Wright defend the traditional view of Jesus as God's Son, as well as that he was self-conscious of his identity and mission as the messiah.

Jesus Seminar members are typical of those who think that all such notions were borrowed from paganism. Neither Borg nor Crossan think that Jesus saw himself as messiah, or as son of God, regarding these titles as later Christian additions. Rudolf Bultmann (1884-1976), who aimed to strip away “mythology” from the gospels, was of the same opinion. According to such thinkers, miracles, Jesus' foreknowledge of his own fate, his self-consciousness as divine, the resurrection and ascension, were all pious additions. Much of what Jesus said was back-projected onto his lips to support Christian theology.

Another tendency in contemporary biblical scholarship is to see Jesus as a loyal but reformist Jew, who made no messianic claims but instead was a teacher and prophet.

Rediscovery of Jesus’ Jewish identity makes many traditional Western depictions of him as an honorary European seem racist. Many black people have been so alienated by that Jesus that they have repudiated Christianity. James Cone argued that Jesus was actually black, and that to be a true follower of Jesus all people—white as well as black—need to identify with the black experience of oppression and powerlessness.[19]

If Jesus did not think he was the messiah, certainly others did. It was this that led to his death sentence, as the title "King of the Jews" was affixed to his cross. The revolutionary and political implications of the Jewish title "Messiah" are not lost by some scholars, who see it as the key to understanding Jesus' life and fate. They reject the views of the Jesus Seminar as tainted with liberal bias.

Christology: Christian Beliefs about Jesus

Christianity is based on the human experience of salvation and rebirth, an outpouring of grace that can come from nowhere else but God. From the standpoint of faith, Jesus must be divine. Christology' is the attempt by the church to explain who Jesus was from the standpoint of faith, as a human being who manifest divinity both in life and in death.

The Nicene Creed (325 C.E.) affirms that Jesus is the eternally begotten Son of God, the second person of the Trinity. The Trinity consists of God the Father, who is un-created and eternal; of God the Son, who is eternally begotten of the Father; and of God the Spirit, who proceeds eternally from the Father (and some add from the Son, the filoque clause inserted at the Council of Toledo in 589).

The Son became human in Jesus. He was also, therefore, wholly human. His human and divine natures were united yet without confusion. His mother, Mary, was a virgin. Jesus was wholly God but not the whole of God. He was of the same substance as the Father. He entered the world for human salvation. He was crucified under Pontius Pilate, died, rose again, descended into hell, and ascended into heaven. He will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead. All will be raised up in order to be judged.

These dogmas were not universally accepted. Some groups, including the Copts of Egypt, teach that Jesus had only one nature, which was divine. The docetics and authors of various Gnostic texts said that Jesus was entirely a spiritual being; he only appeared to be human. The followers of Marcion (d. 160) divorced Jesus from his Jewish background, contending that Jesus' God and the God of the Jews were different.

Others took the opposite tack, stressing Jesus' humanity. Arius (d. 336) taught that he was not co-eternal with God, but had been created in time. Others taught that Jesus was an ordinary man, whom God adopted (perhaps at his baptism) as his son. The earliest Jewish Christians, who later became known as Ebionites, saw Jesus as a good Jew who never intended to establish a separate religion. Their Jesus pointed towards God but did not claim to be God. Paul began to develop a theology of Jesus as the "new Adam who comes to restore the sin of the first Adam” (1 Cor. 15:45-49, Rom. 5:12-19).

Discussion and debate on all these doctrinal issues continues within Christian theology. Many point out that the language the church chose to describe the “persons” of the Trinity, or Jesus as “Son of God,” used terms that were common at the time but which were not meant to be exact, scientific definitions. Rather, they expressed the Christian conviction that God had acted and spoken through Jesus, who enjoyed an intimate relationship with God, and whose life and death connected them to God in a way that renewed their lives, overcame sin and set them on a new path of love, service and spiritual health.

Christians today might choose different language. The nineteenth-century German theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834), dubbed the “father of modern theology,” argued that Jesus can be distinguished from all other men and women because he achieved a complete state of dependence on God, of God-consciousness.

An Asian appreciation of the divinity and humanity of Christ sees in Jesus' sorrows an image of the sorrows and pain of God himself. Japanese theologian Kazoh Kitamori describes the "Pain of God" as encompassing: (1) the pain God feels over man's sin, (2) the suffering God shared by assuming Christ and taking on the pains of human life, and (3) the suffering God experienced when his only Son was tortured and killed. Conversely, by helping people in their suffering, we help to alleviate the suffering of God and Christ, for "Whatever you did to the least of these, you did for Me" (Matt. 25:31-40).[20]

Jesus in other faiths

Islam

According to mainstream Islam, Jesus (Isa in the Qur'an) was one of God's highest ranked and most beloved prophets, ranked among the righteous. He was sent specifically to guide the Children of Israel (see Q6:85). He was neither God nor the son of God, but rather a human prophet, one of many prophets sent over history to guide mankind. Jesus' message to mankind was originally the same as all of the other prophets, from Adam to Muhammad, but has been distorted by those who claim to be its adherents (Q4:171). The Qur'an also calls him Al-Masih (messiah), but the meaning of this is vague and carries little significance. Christians are said to exaggerate Jesus' importance, committing excess in their religion. Jesus is not nor did he claim to be one of the trinity (Q4:171), although the Qur'an appears to describe a trinity of Father, mother (Mary) and Son (Q5:117). Jesus taught his followers to “worship Allah, my Lord.”

Jesus was born miraculously without a human biological father by the will of God (Q19:20-21). Thus is Jesus compared with Adam, whom God “created from dust” (Q3:59). His mother, Mary (Maryam in Arabic), is among the most saintly, pious, chaste, and virtuous women ever. Jesus performed miracles, but only by the “permission” of God. The Qur'an mentions, among other miracles, that he raised the dead, restored sight to the blind and cured lepers. He also made clay bird fly (Q3:49 5:109-110).

Jesus renounced all worldly possessions and lived a life of strict nonviolence, abstaining from eating meat and also from drinking alcohol. The simplicity of Jesus’ lifestyle, his kindness to animals and his other-worldliness are stressed in Sufi writings.[21] Jalal al-Din Rumi (d. 1273), founder of the Mevelvi order, equated Jesus with divine love, whose selfless, other-centered nature poured out in “healing love” of others.

Jesus received a gospel from God, called (in Arabic) the Injeel and corresponding to the New Testament (Q3:3). However, Muslims hold that the New Testament we have today has been altered and does not accurately represent the original. Some Muslims accept the Gospel of Barnabas as the most accurate testament of Jesus. Muslims attribute this to Barnabas, who parted company from Saint Paul in Acts 16:39. Almost all non-Muslim scholars regard this text as a medieval production, and thus not an authentic text.

As mentioned above, Jesus was neither killed nor crucified, but God made it appear so to his enemies (Q4:157). Some Muslim scholars (notably Ahmad Deedat) maintain that Jesus was indeed put up on the cross, but did not die on it. He was revived and then ascended bodily to heaven, while others say that it was actually Judas who was mistakenly crucified by the Romans. However, Q19:34 has Jesus say, “peace is on me the die I was born, the day I shall die and the day I shall be raised up,” which gives the Christian order of events. Thus, the Qur'an does say that Jesus will die but most Muslims regard this as a future event, after his return. Q3:55 says that God will “raise” Jesus to Himself.

Muslims believe in the Second Coming. Jesus is alive in heaven and will return to Earth in the flesh with Imam Mahdi to defeat the dajjal (the anti-Christ in Islamic belief), once the world has become filled with injustice. Many Muslims think that Jesus will then marry, have children, and die a natural death.

Finally, Jesus predicted Muhammad (Q61:6), based on the Arabic translation of "Comforter" (παράκλητος) in John 14:16 as "Ahmad," a cognate of Muhammad.

Judaism

Judaism does not see Jesus as a messiah and also rejects the Muslim belief that Jesus was a prophet. Religious Jews are still awaiting the coming of the messiah (a notable exception concerns many members of the Chabad Lubavitch, who view their last Rebbe as being the messiah). As for the historical personality of Jesus, Judaism has fewer objections to quotes attributed to him than they do with subsequent confessions by early Christian adherents, Paul in particular. His ethical teachings in particular are viewed as largely in agreement with the best of rabbinic thought. While the New Testament sets Jesus over against the Jews in arguments over matters of doctrine and law, Jewish scholars see these as debates within the Judaism of his time. For example, the gospel writers' accounts of Jesus healing on the Sabbath (Luke 6:6-11, Matt. 12:9-14) depicts the Pharisees as furious over his breach of the law, when in fact the Talmud contains reasoned discussions of the question by learned rabbis and in the end opts for Jesus' position.

Some Jewish scholars believe that Jesus is mentioned as Yeshu in the Jewish Talmud, usually in ridicule and as a mesith (enticer of Jews away from the truth), although other scholars dispute this. Joseph Klausner, a prominent Israeli scholar, was vigorous in asserting the Judaism of Jesus.

The primary reasons why Jesus is not accepted as the Jewish messiah are as follows:

- Jesus did not fulfill the major Biblical prophecies regarding what the Messiah is to do—bring the Jews back to the Land of Israel, establish peace on earth, establish God's earthly reign from Jerusalem, etc.

- Instead, the followers of Jesus have done quite the opposite: persecuting the Jews and driving them from country to country, and generally making their life miserable for nearly two thouand years.

- The New Testament calls Jesus the Son of God and makes him out to be a divine being. In Judaism, any thought to make a man into God—or to establish via the doctrine of the Trinity that there are three Gods—is tantamount to idolatry. There is only one God.

- The Jewish messiah must descend patrilineally from King David. Jesus' father is God. His claim to be of the lineage of David is through Joseph, but he was not the father.

- Jesus was executed, suffering a shameful death. The Jewish messiah should not be killed before he has established the Kingdom of God, the new "Garden of Eden," on Earth. Maimonides rules concerning one who is killed that “it is certain the he is not the one whom the Torah has promised” (Laws of Kings 11:4).

Christian efforts to convert Jews based upon so-called proofs of Jesus' messiahship, such as found in the gospel of Matthew, are completely ineffective in convincing Jews, because they do not share the Christian presuppositions about the meaning of the concept "messiah." Since the concept of messiah originates in the Hebrew Bible, Jews believe that they own the correct meaning of the concept, which Christians have distorted to fit their theories about Jesus.

Hinduism

Some distinguished Hindus have written on Jesus. Most regard him as a manifestation of God but not as the only one—Jesus is one among many. See Vivekananda (1963-1966), who depicted Jesus as a jibanmukti, one who had gained liberation while still alive and love for the service of others. Some point to similarities between Jesus and Krishna.[22] Mahatma Gandhi greatly admired Jesus but was disappointed by Christians, who failed to practice what they preach. Dayananda Sarasvati (1824-1883) thought the gospels silly, Jesus ignorant and Christianity a “hoax.”[23] Hindu scholars are less interested in the historicity of Jesus.

Other perspectives

- Unitarians believe that Jesus was a good man, but not God. Some Muslim writers believe that Christianity was originally Unitarian, and it has been suggested that Unitarians might help to bridge the differences between Christianity and Islam.[24]

- The Bahá'í Faith considers Jesus to be a manifestation (prophet) of God, while not being God incarnate.

- Atheists, by definition, have no belief in a divinity—and thus not in any divinity of Jesus. Some doubt he lived; some regard him as an important moral teacher, and some as a historical preacher like many others.

- Some Buddhists believe Jesus may have been a Bodhisattva, one who gives up his own Nirvana to help others reach theirs. The fourteenth Dalai Lama and the Zen Buddhist Thich Nhat Hanh have both written sympathetically on Jesus. Kersten (1986) thinks that Jesus and the Essenes were Buddhist. Many in the Surat Shabda Yoga tradition regard Jesus as a Sat Guru.

- The Ahmadiyya Muslim Movement, founded by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (1835-1908), claims that Jesus survived the crucifixion and later traveled to India, where he lived as a prophet and died as Yuz Asaf.[25] When Jesus was taken down from the cross, he had lapsed into a state similar to Jonah's state of “swoon” in the belly of a fish (Matt. 12:40). A medicine known as Marham-e-Issa (Ointment of Jesus) was applied to his wounds and he revived. Jesus then appeared to Mary Magdalene, his apostles and others with the same (not resurrected) human body, evidenced by his human wounds and his subsequent clandestine rendezvous over about forty days in the Jerusalem surroundings. Then he purportedly traveled to Nasibain, Afghanistan and Kashmir, India in search of the lost tribes of Israel.

- Elizabeth Claire Prophet, perhaps influenced by the Ahmadiyya movement, claimed that Jesus traveled to India after his crucifixion.

- The New Age Movement has reinterpreted the life and teaching of Jesus in a variety of ways. He has been claimed as an “Ascended Master” by Theosophy and some of its offshoots; related speculations have him studying mysticism in the Himalayas or hermeticism in Egypt in the period between his childhood and his public career.

- The Unification Church teaches that Jesus' mission was to restore all creation to its original ideal prior to the Fall of Man, and this mission required him to marry. Due to opposition, Jesus went to the cross as a secondary course to bring spiritual salvation, but the fullness of salvation—the Kingdom of God—awaits his Second Coming. The person of the Second Coming will take up the unfinished work of Christ, including marrying and establishing the family of the new Adam to which all humankind will be engrafted.

Relics

Many items exist that are purported to be authentic relics of Jesus. The most famous alleged relics of Jesus are the Shroud of Turin, said to be the burial shroud used to wrap his body; the Sudarium of Oviedo, which is claimed to be the cloth which was used to cover his face; and the Holy Grail, which is said to have been used to collect his blood during his crucifixion and possibly used at the Last Supper. Many modern Christians, however, do not accept any of these as true relics. Indeed, this skepticism has been around for centuries, with Desiderius Erasmus joking that so much wood formed pieces of the "True Cross" displayed as relics in the cathedrals of Europe that Jesus must have been crucified on a whole forest.

Artistic portrayals

Jesus has been portrayed in countless paintings and sculptures throughout the Middle Ages, Renaissance, and modern times. Often he is portrayed as looking like a male from the region of the artist creating the portrait. According to historians, forensic scientists and genetics experts, he was most likely a bronze-skinned man—resembling a modern-day man of Middle Eastern descent.

Jesus has been featured in many films and media forms, sometimes seriously, and other times satirically. Many of these portrayals have attracted controversy, either when they were intended to be based on genuine Biblical accounts (such as Mel Gibson's 2004 film The Passion of the Christ and Pier Pasolini's The Gospel According to St. Matthew) or based on alternative interpretations (such as Martin Scorsese's The Last Temptation of Christ). In this film, Jesus is tempted to step down from the cross, to marry and have children. Later, when he realizes that he had been tempted to do this by Satan, he returns to the cross, and dies.

Other portrayals have attracted less controversy, such as the television ministry’s Jesus of Nazareth by Franco Zeffirelli. Another theme is bringing Jesus' story into the present day (such as in Jesus of Montreal) or imagining his second coming (in The Seventh Sign, for example). In many films Jesus himself is a minor character, used to develop the overall themes or to provide context. For example, in the screen adaptation of Lew Wallace's classic Ben-Hur and The Life of Brian, Jesus only appears in a few scenes.

In music, many songs refer to Jesus and Jesus provides the theme for classical works throughout music history.

Notes

- ↑ Robert Miller, The Complete Gospels (Santa Rosa, CA: Polebridge Press, 1994, ISBN 0944344305).

- ↑ Morton Smith, The Secret Gospel: The Discovery and Interpretation of the Secret Gospel According to Mark (Dawn Horse Press, 2005, ISBN 978-1570972034)

- ↑ Stephen C. Carlson, The Gospel Hoax: Morton Smith's Invention of Secret Mark (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2005, ISBN 1932792481).

- ↑ The Lost Gospel of Judas Iscariot? NPR, April 6, 2006. Retrieved June 17, 2022.

- ↑ Holger Kersten, Jesus Lived in India (Shaftesbury, Dorset: Element Books, 1986, ISBN 1852305509), 196.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Robert W. Funk, The Five Gospels: What Did Jesus Really Say? The Search for the Authentic Words of Jesus (San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFransisco, ISBN 006063040X), 221.

- ↑ Josephus' Account of Jesus: The Testimonium Flavianum. Retrieved June 17, 2022.

- ↑ James Orr, The Infancy Gospel of Thomas (Independently published, 2017, ISBN 978-1549853418).

- ↑ Clinton Bennett, In Search of Jesus: Insider and Outsider Images (New York: Continuum, 2001, ISBN 0826449166), 86.

- ↑ Bruce Chilton, Rabbi Jesus (New York: Doubleday, 2000, ISBN 038549792X).

- ↑ William Phipps, The Sexuality of Jesus (Cleveland, OH: The Pilgrim Press, 1996, ISBN 0829811443), 174.

- ↑ Elizabeth S. Fiorenza, Sharing Her World: Feminist Interpretations in Context (Boston: Beacon Press, 1998, ISBN 0807012335).

- ↑ Scholarly treatments include Richard Atwood, Mary Magdalene in the New Testament Gospels and Early Tradition (European University Studies. Series XXIII Theology. Vol. 457) (New York: Peter Lang, 1993); Antti Marjanen, The Woman Jesus Loved: Mary Magdalene in the Nag Hammadi Library & Related Documents (Nag Hammadi and Manichaean Studies, XL) (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1996); Karen L. King, The Gospel of Mary of Magdala: Jesus and the First Woman Apostle (Santa Rosa: Polebridge Press, 2003); Bruce Chilton, Mary Magdalene: A Biography (New York: Doubleday, 2005); Marvin Meyer, The Gospels of Mary: The Secret Tradition of Mary Magdalene, the Companion of Jesus (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 2004); Susan Haskins, Mary Magdalen: Myth and Metaphor (New York: Harcourt, 1994); Esther De Boer, Mary Magdalene: Beyond the Myth (Philadelphia: Trinity Press International, 1997); Ann Graham Brock, Mary Magdalene, The First Apostle: The Struggle for Authority (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Divinity School, 2003); Jane Schaberg, The Resurrection of Mary Magdalene: Legends, Apocrypha, and the Christian Testament (New York: Continuum, 2002).

- ↑ Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh, and Henry Lincoln, Holy Blood, Holy Grail: The Secret History of Jesus (New York: Delacore Press, 2005, ISBN 038534001X).

- ↑ Dan Brown, The Da Vinci Code (New York: Random House, 2003, ISBN 0307277674).

- ↑ Robert J. Miller (ed.), The Apocalyptic Jesus: A Debate (Santa Rosa, CA: Polebridge Press, 2001, ISBN 0944344895).

- ↑ Albert Schwietzer, The Quest of the Historical Jesus: A Critical Study of its Progress from Reimarus to Wrede (New York: Scribner, 1968, ISBN 0020892403).

- ↑ Bennett, 87.

- ↑ James Cone, A Black Theology of Liberation (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1990, ISBN 0883446855).

- ↑ Kazoh Kitamori, Theology of the Pain of God (Wipf and Stock, 2005, ISBN 978-1597522564).

- ↑ Bennett, 279-280.

- ↑ Bennett, 299-301.

- ↑ Bennett, 327-328.

- ↑ Bennett, 283-285.

- ↑ Ahmadiyya Muslim Community, Jesus in India by Hadhrat Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, The Promised Messiah and Mahdi Founder of the Ahmadiyya Movement in Islam. Retrieved June 17, 2022.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aland, Kurt. The Greek New Testament. American Bible Society, 4th ed., 1998. ISBN 3438051133

- Albright, William F. Yahweh and the Gods of Canaan: An Historical Analysis of Two Contrasting Faiths. New York: Doubleday, 1969. ISBN 0931464013

- Baigent, Michael, Richard Leigh, and Henry Lincoln. Holy Blood, Holy Grail: The Secret History of Jesus. New York: Delacore Press, 1982. Illustrated edition, 2005. ISBN 038534001X

- Baigent, Michael, and Richard Leigh. The Dead Seas Scrolls Deception. New York: Simon and Schuster. Third edition, 1992. ISBN 0671734547

- Barnett, Paul. Is the New Testament Reliable? London: Inter-Varsity Press, 2005. ISBN 0830827684

- Bennett, Clinton. In Search of Jesus: Insider and Outsider Images. New York: Continuum, 2001. ISBN 0826449166

- Borg, Marcus J. Conflict, Holiness and Politics in the Teaching of Jesus. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity. Second edition, 1998. ISBN 156338227X

- Brown, Dan. The Da Vinci Code. New York: Random House, 2003. ISBN 0307277674

- Bruce, F. F. The New Testament Documents: Are they reliable? Eerdmans, 2003. ISBN 978-0802822192

- Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1970. ISBN 0691017840

- Carlson, Stephen C. The Gospel Hoax: Morton Smith's Invention of Secret Mark. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2005. ISBN 1932792481

- Chamberlain, Houston S. Foundations of the Nineteenth Century. Adamant Media Corporation, 2003. ISBN 978-1402154591

- Chilton, Bruce. Rabbi Jesus. New York: Doubleday, 2000. ISBN 038549792X

- Cone, James. A Black Theology of Liberation. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1990. ISBN 0883446855

- Crossan, John Dominic. Who Killed Jesus?: Exposing the Roots of Anti-Semitism in the Gospel Story of the Death of Jesus. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1996. ISBN 0060614803

- Davenport, Guy and Benjamin Urrutia. The Logia of Yeshua: The Sayings of Jesus. Jackson, TN: Counterpoint, 1996. ISBN 1887178708

- Doherty, Earl. The Jesus Puzzle. Did Christianity Begin with a Mythical Christ?: Challenging the Existence of an Historical Jesus. Age of Reason Publications, 2005. ISBN 0968601405

- Dalai Lama, the 14th. The Good Heart: A Buddhist Perspective on the Teaching of Jesus. Boston, MA: Wisdom Publications, 1996. ISBN 0861711386

- Dunn, James D.G. Jesus, Paul and the Law. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1990. ISBN 0664250955

- Eisenman, Robert. James the Brother of Jesus: The Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Early Christianity and the Dead Sea Scrolls. New York: Penguin (Non-Classics), 1998. ISBN 014025773X

- Fiorenza, Elizabeth S. Sharing Her World: Feminist Interpretations in Context. Boston: Beacon Press, 1998. ISBN 0807012335

- Fredriksen, Paula. Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews: A Jewish Life and the Emergence of Christianity. New York: Vintage, 2000. ISBN 0679767460

- Fredriksen, Paula. From Jesus to Christ: The Origins of the New Testament Images of Christ. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300084579

- Funk, Robert W. The Five Gospels: What Did Jesus Really Say? The Search for the Authentic Words of Jesus. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFransisco, 1993. Reprint ed., 1997. ISBN 006063040X

- Gaus, Andy. The Unvarnished New Testament. York Beach, NE: Phanes Press, 1991. ISBN 0933999992

- Gandhi, M. K. The Message of Jesus Christ. Canton, ME: Greenleaf Books, 1980 (original 1940). ISBN 0934676208

- Goulder, Michael. St Paul versus St Peter: A Tale of Two Missions. Louisville, KY: Westminster/John Knox, 1995. ISBN 0664255612

- Hahn, Thich Naht. Living Buddha, Living Christ. New York: Riverhead, 1995. ISBN 1573225681

- Kersten, Holger. Jesus Lived in India. Shaftesbury, Dorset: Element Books, 1986. ISBN 1852305509

- Kitamori, Kazoh. Theology of the Pain of God. Wipf and Stock, 2005. ISBN 978-1597522564

- Klausner, Joseph. Jesus of Nazareth. New York: Macmillan, 1925 (original). NewYork: Bloch Publishing Company, 1997. ISBN 0819705659

- Lewis, C. S. Mere Christianity. Nashville, TN: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 1999. ISBN 0805493476

- Marshall, Ian H. I Believe in the Historical Jesus. Vancouver, BC: Regent College Publishing, 2001. ISBN 1573830194

- McDowell, Josh. The New Evidence that Demands a Verdict. Nashville, TN: Nelson Reference, 1999. ISBN 0918956463 (vol. 1), ISBN 0918956730 (vol. 2)

- Meier, John P. A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus. New York: Doubleday, 1991. ISBN 0385264259

- Mendenhall, George E. Ancient Israel's Faith and History: An Introduction to the Bible in Context. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001. ISBN 0664223133

- Messori, Vittorio Jesus Hypotheses. Slough, UK: St Paul Publications, 1977. ISBN 0854391541

- Metzger, Bruce. Textual Commentary on the Greek NT. Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft. Second edition, 1994. ISBN 3438060108

- Metzger, Bruce. The Canon of the New Testament Canon. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 0198269544

- Miller, Robert. The Complete Gospels. Santa Rosa, CA: Polebridge Press. Expanded ed., 1994. ISBN 0944344305

- Miller, Robert J. (ed.). The Apocalyptic Jesus: A Debate. Santa Rosa, CA: Polebridge Press, 2001. ISBN 0944344895

- Orr, James. The Infancy Gospel of Thomas. Independently published, 2017. ISBN 978-1549853418

- Pagels, Elaine. “The Meaning of Jesus.” Books and Culture: A Christian Review (March/April 1999): 40.

- Pelikan, Jaroslav. Jesus Through the Centuries: His Place in the History of Culture. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1985. Reprint edition, 1999. ISBN 0300079877

- Prophet, Elizabeth Clare. The Lost Years of Jesus. Corwin Springs, MT: Summit University Press, 1987. ISBN 091676687X

- Phipps, William. The Sexuality of Jesus. Cleveland, OH: The Pilgrim Press, 1996. ISBN 0829811443

- Rahim, Muhammad 'Ata-ur. Jesus: Prophet of Islam. Elmhurst, NY: Tahrike Tarsile Qur'an, 1992. ISBN 1879402114

- Robertson, John M. Christianity and Mythology. Alpha Editions, 2020 (original 1900). ISBN 978-9354010644

- Robertson, John M. Pagan Christs: Studies in Comparative Hierology. HardPress Publishing, 2012 (original 1911). ISBN 978-1290878043

- Sanders, E. P. The historical figure of Jesus. New York: Penguin, 1993. ISBN 0140144994

- Sanders, E. P. Jesus and Judaism. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1987. ISBN 0800620615

- Schaberg, Jane. Illegitimacy of Jesus: A Feminist Theological Interpretation of the Infancy Narratives. New York: Crossroad Press. ISBN 0940989603

- Schwietzer, Albert. The Quest of the Historical Jesus: A Critical Study of its Progress from Reimarus to Wrede. New York: Scribner, 1968. ISBN 0020892403

- Smith, Morton. Jesus the Magician. San Francisco: Harper & Rowe, 1978. ISBN 0060674121

- Smith, Morton. The Secret Gospel: The Discovery and Interpretation of the Secret Gospel According to Mark. Dawn Horse Press, 2005. ISBN 978-1570972034

- Talbert, Charles (ed.). Reimarus' Fragments. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1970. ISBN 0800601521

- Theissen, Gerd and Annette Merz. The Historical Jesus: A Comprehensive Guide. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 2003. ISBN 0800631226

- Theissen, Gerd. The Shadow of the Galilean: The Quest of the Historical Jesus in Narrative Form. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1987. ISBN 0800620577

- Thiering, Barbara. Jesus the Man. London, Doubleday, 1992. ISBN 0868244449

- Tolstoy, Leo. The Kingdom of God is Within You. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1985. ISBN 0803294042

- Vermes, Geza. Jesus the Jew: A Historian's Reading of the Gospels. London: SCM, 1973. ISBN 0800614437

- Walvoord, John F. Jesus Christ Our Lord. Chicago, IL: Moody Press, 1969. ISBN 0802443265

- Wilson, Ian. Jesus: The Evidence. London: Pan Books, 1985. ISBN 0297835297

- Yoder, John H. The Politics of Jesus. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1994. ISBN 0802807348

- Vivekananda, Swami. Christ the Messenger. Kolkata: Advaita Ashrama (Publication Department), 2004. ISBN 8175050632

- Wallace, Lewis. Ben Hur. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998 (original 1880). ISBN 0192831992

- Weiss, Johannes. Jesus Proclamation of the Kingdom of God. Philadelphia, PA: Fortress Press, 1971 (German original, 1892). ISBN 080060153X

- Wells, George Herbert. Did Jesus Exist? London: Elek Books, 1975. ISBN 0236310011

- Wheless, Joseph. Forgery in Christianity: A Documented Record of the Foundations of the Christian Religion. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 1997 (first published by Knopf, 1930). ISBN 1564592251

- Wright, Tom. Who was Jesus? London: SPCK, 1992; Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eermands, 1993. ISBN 0802806945

- Wright, Tom. Jesus and the Victory of God. London, SPCK 1996. ISBN 0281047170

In some editions of Jewish Antiquities by the Jewish historian Josephus Book 18, chapter 3, paragraph 3 refer to Jesus. Most scholars believe that these passages were added to Josephus's text by later Christians. The Arabic version of Josephus is free of these apparent Christian interpolations, but still makes it clear that Pilate ordered the execution of Jesus.

External links

All links retrieved July 31, 2022.

Christian views

- Jesus Christ Only – Articles, sermons and quotes dedicated to Jesus

- Jesus Christ Catholic Encyclopedia.

- All About Jesus Christ – A conservative Christian view

- Is Jesus God? – A fundamentalist view

Islamic views

- Jesus - An Islamic Perspective – Islam from Inside

- The Qur'an on Jesus' divinity – Islam from Inside

- Jesus' second coming in Islam

- Jesus, the prophet of Allah

Other religious views

- Jesus of Nazareth Jewish Encyclopedia.

- The Words.com – Website that organizes Jesus' sayings by topic

- Refuting Missionaries by Hayyim ben Yehoshua, – A Jewish response to Christian missionaries

Historical and Other

- Did Jesus of Nazareth Really Exist? All Sides to the Question Religious Tolerance.

- The Lost Years of Jesus: The Life of Saint Issa

- Yahushua is the True Name of the Messiah EliYah Ministries.

- Contemporary Scholarship and the Historical Evidence for the Resurrection of Jesus Christ by William Lane Craig

- From Jesus to Christ – A Frontline PBS TV series documentary on Jesus and early Christianity

- Jesus The Man edited by Lewis Loflin

- “Christ and the Other Religions” by Michael Fitzgerald, Commission for Interreligious Dialogue.

- Jesus Never Existed Articles and videos by Kenneth Humphreys

- Linkages between two God-men saviors: Christ and Krishna Religious Tolerance.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 21:14:44 | 378 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Christ | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF