Hans Christian Ørsted

From Handwiki

From Handwiki Hans Christian Ørsted | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 14 August 1777 Rudkøbing, Denmark-Norway |

| Died | 9 March 1851 (aged 73) Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Nationality | Danish |

| Alma mater | University of Copenhagen (PhD, 1799)[1] |

| Known for | Discovery of electromagnetism and Aluminium[1] Ørsted's law Thought experiment |

| Awards | Copley Medal (1820) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics, chemistry, aesthetics |

| Institutions | University of Copenhagen, Technical University of Denmark (Founder and Principal) |

| Influences | Immanuel Kant |

| Signature | |

| |

Hans Christian Ørsted (/ˈɜːrstɛd/ UR-sted,[2] Danish: [ˈhænˀs ˈkʰʁestjæn ˈɶɐ̯steð] (![]() listen); often rendered Oersted in English; 14 August 1777 – 9 March 1851) was a Danish physicist and chemist who discovered that electric currents create magnetic fields, which was the first connection found between electricity and magnetism. Oersted's law and the oersted unit (Oe) are named after him.

listen); often rendered Oersted in English; 14 August 1777 – 9 March 1851) was a Danish physicist and chemist who discovered that electric currents create magnetic fields, which was the first connection found between electricity and magnetism. Oersted's law and the oersted unit (Oe) are named after him.

A leader of the Danish Golden Age, Ørsted was a close friend of Hans Christian Andersen and the brother of politician and jurist Anders Sandøe Ørsted, who served as Prime Minister of Denmark from 1853 to 1854.

Early life and studies

Ørsted was born in Rudkøbing in 1777. As a young boy he developed an interest in science while working for his father, who owned the local pharmacy.[3] He and his brother Anders received most of their early education through self-study at home, going to Copenhagen in 1793 to take entrance exams for the University of Copenhagen, where both brothers excelled academically. By 1796, Ørsted had been awarded honors for his papers in both aesthetics and physics. He earned his doctorate in 1799 for a dissertation based on the works of Kant entitled The Architectonics of Natural Metaphysics.

In 1800, Alessandro Volta reported his invention of the voltaic pile, which inspired Ørsted to investigate the nature of electricity and to conduct his first electrical experiments. In 1801, Ørsted received a travel scholarship and public grant which enabled him to spend three years traveling across Europe. He toured science headquarters throughout the continent, including in Berlin and Paris.[4]

In Germany Ørsted met Johann Wilhelm Ritter, a physicist who believed there was a connection between electricity and magnetism. This idea made sense to Ørsted as he subscribed to Kantian thought regarding the unity of nature.[3][5] Ørsted's conversations with Ritter drew him into the study of physics. He became a professor at the University of Copenhagen in 1806 and continued research on electric currents and acoustics. Under his guidance the university developed a comprehensive physics and chemistry program and established new laboratories.

Ørsted welcomed William Christopher Zeise to his family home in autumn 1806. He granted Zeise a position as his lecturing assistant and took the young chemist under his tutelage. In 1812, Ørsted again visited Germany and France after publishing Videnskaben om Naturens Almindelige Love and Første Indledning til den Almindelige Naturlære (1811).

Ørsted was the first modern thinker to explicitly describe and name the thought experiment. He used the Latin-German term Gedankenexperiment circa 1812 and the German term Gedankenversuch in 1820.[6]

Ørsted designed a new type of piezometer to measure the compressibility of liquids in the 1820s.[7]

Electromagnetism

File:17. Естердов експеримент.ogv

| Part of a series of articles about |

| Electromagnetism |

|---|

|

|

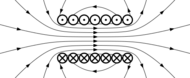

In 1820, Ørsted published his discovery that a compass needle was deflected from magnetic north by a nearby electric current, confirming a direct relationship between electricity and magnetism.[8] The often reported story that Ørsted made this discovery incidentally during a lecture is a myth. He had, in fact, been looking for a connection between electricity and magnetism since 1818, but was quite confused by the results he was obtaining.[9][10]

His initial interpretation was that magnetic effects radiate from all sides of a wire carrying an electric current, as do light and heat. Three months later, he began more intensive investigations and soon thereafter published his findings, showing that an electric current produces a circular magnetic field as it flows through a wire.[11][9] For his discovery, the Royal Society of London awarded Ørsted the Copley Medal in 1820 and the French Academy granted him 3,000 francs.

Ørsted's findings stirred much research into electrodynamics throughout the scientific community, influencing French physicist André-Marie Ampère's developments of a single mathematical formula to represent the magnetic forces between current-carrying conductors. Ørsted's work also represented a major step toward a unified concept of energy.

The Ørsted effect brought about a communications revolution due to its application to the electric telegraph. The possibility of such a telegraph was suggested almost immediately by mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace and Ampère presented a paper based on Laplace's idea the same year as Ørsted's discovery.[12] However, it was almost two decades before it became a commercial reality.

Later years

Ørsted was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in 1822, a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1829,[13] and a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1849.[14]

He founded Selskabet for Naturlærens Udbredelse (da) (SNU), a society to disseminate knowledge of the natural sciences, in 1824. He was also the founder of predecessor organizations which eventually became the Danish Meteorological Institute and the Danish Patent and Trademark Office. In 1829, Ørsted founded Den Polytekniske Læreanstalt ('College of Advanced Technology') which was later renamed the Technical University of Denmark (DTU).[15]

In 1825, Ørsted made a significant contribution to chemistry by producing aluminium in a near-pure form for the first time.[16] In 1808, Humphry Davy had predicted the existence of the metal which he gave the name of alumium. However his attempts to isolate it using electrolysis processes were unsuccessful. The closest he came was an aluminum-iron alloy.[17][18] Ørsted was the first to isolate the element via a reduction of aluminium chloride. Although the aluminium alloy he extracted still contained impurities, he is credited with discovery of the metal. His work was developed further by Friedrich Wöhler who obtained aluminium powder on October 22, 1827, and solidified balls of molten aluminium in 1845. Wöhler is credited with the first isolation of the metal in a pure form.[18][19]

.jpg)

Ørsted died in Copenhagen in 1851, aged 73, and was buried in the Assistens Cemetery.

Legacy

The centimetre-gram-second system (CGS) unit of magnetic induction (oersted) is named for his contributions to the field of electromagnetism.

Toponymy

The Ørsted Park in Copenhagen was named after Ørsted and his brother in 1879. The streets H.C. Ørsteds Vej in Frederiksberg and H. C. Ørsteds Allé in Galten are also named after him.

The buildings that are home to the Department of Chemistry and the Institute for Mathematical Sciences at the University of Copenhagen's North Campus are named the H.C. Ørsted Institute, after him. A dormitory named H. C. Ørsted Kollegiet is located in Odense.

The first Danish satellite, launched 1999, was named after Ørsted.

Monuments and memorials

A statue of Hans Christian Ørsted was installed in the Ørsted Park in 1880. A commemorative plaque is located above the gate on the building in Studiestræde where he lived and worked. The 100 danske kroner note issued from 1950 to 1970 carried an engraving of Ørsted.

In 1885, a statue of Ørsted was installed in the Oxford University Museum of Natural History.

Awards and lectures

Two medals are awarded in Ørsted's name: the Oersted Medal for notable contributions in the teaching of physics in America, awarded by American Association of Physics Teachers, along with the H. C. Ørsted Medal for Danish scientists, awarded by the Danish Selskabet for Naturlærens Udbredelse (Society for the Dissemination of Natural Science), founded by Ørsted.

The H.C. Ørsted Lectureship is awarded to two prominent researchers annually.

Here is a list of some of the previous H.C. Ørsted lecturers:

- Dr. Jack Connerney, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, USA

- Professor Michaël Grätzel, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, EPFL

- Professor Pierre-Gilles de Gennes, Collège de France, Nobel Laureate in Physics

- Professor Ivar Giaever, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Nobel Laureate in Physics

- Professor Paul F. Hoffman, Sturgis Hooper Professor of Geology, Harvard University

- Professor Leroy Hood, William Gates III Professor, Institute for Systems Biology

- Professor Sir Harold Kroto, University of Sussex, Nobel Laureate in Chemistry

- Professor Sir Roger Penrose, University of Oxford

- Professor Julius Rebek, Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology at The Scripps Research Institute

- Professor Cees Dekker, Nanophysics, TU Delft

- Professor Subra Suresh, Materials Science and Biological Engineering, MIT

- Professor Everett Peter Greenberg, Microbiology, University of Washington

- Honorary Professor Sir John Meurig Thomas, University of Cambridge

- Professor Ahmed Zewail, California Institute of Technology, Nobel Laureate in Chemistry

- Professor Nathan S. Lewis, Chemistry, California Institute of Technology

- Professor Sajeev John, University of Toronto

- Professor Howard A. Stone, Fluid Mechanics, Princeton University

- Professor of Physics and Applied Physics Lene Vestergaard Hau, Harvard University

- Professor Stanley N. Cohen, School of Medicine, Stanford University

- Professor Juan de Pablo,[20] Institute for Molecular Engineering, University of Chicago

- Professor Mario Molina, University of California, San Diego, Nobel Prize Winner.[21]

Writings

File:Ørsted - Der Geist in der Natur, 1854 - BEIC 683267.tiff Ørsted was a published writer and poet. His poetry series Luftskibet ("The Airship") was inspired by the balloon flights of fellow physicist and stage magician Étienne-Gaspard Robert.[22] Shortly before his death, he submitted a collection of articles for publication under the title Aanden i Naturen ("The Soul in Nature"). The book presents Ørsted's life philosophy and views on a wide variety of issues.[23]

- (in fr) Ansicht der chemischen Naturgesetze, durch die neueren Entdeckungen gewonnen. Paris: Jean Gabriel Dentu. 1813. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=12236149.

- (in de) Aanden i Naturen. 1. Leipzig: Lorck. 1854. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=682714.

- (in de) Aanden i Naturen. 2. Leipzig: Lorck. 1854. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=683267.

- Recherches sur l'identité des forces chimiques et électriques (French; translated from German by Mr. Marcel de Serres). Paris : J.G. Dentu, imprimeur-libraire. 1813.

1813 copy of Recherches sur l'identité des forces chimiques et électriques, translated from German by Mr. Marcel de Serres

Title page to Recherches sur l'identité des forces chimiques et électriques

Introduction to Recherches sur l'identité des forces chimiques et électriques

See also

- History of aluminium

- James Clerk Maxwell

- Michael Faraday

- Gian Domenico Romagnosi, who observed an electrostatic attraction of a compass needle

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 rare-earth-magnets.com

- ↑ "Oersted". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Hans Christian Ørsted". Hebrew University of Jerusalem. http://chem.ch.huji.ac.il/history/oersted.htm.

- ↑ Inspiration fra Europa - planer i København Niels Bohr Institute

- ↑ Brian, R.M. & Cohen, R.S. (2007). Hans Christian Ørsted and the Romantic Legacy in Science, Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, Vol. 241.

- ↑ Witt-Hansen, J., "H.C. Ørsted, Immanuel Kant and the Thought Experiment", Danish Yearbook of Philosophy, Vol.13, (1976), pp. 48–65.

- ↑ Aitken, Frédéric; Foulc, Jean-Numa (2019). "Chapter 1". From deep sea to laboratory. 3, From Tait's work on the compressibility of seawater to equations-of-state for liquids. London, UK: ISTE-WILEY. ISBN 9781786303769. http://www.iste.co.uk/book.php?id=1534.

- ↑ John Joseph Fahie, A History of the Electric Telegraph to the Year 1837, p. 274, London: E. & F.N. Spon, 1884 OCLC 559318239.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Martins, Roberto de Andrade, Resistance to the discovery of electromagnetism: Ørsted and the symmetry of the magnetic field", in: Fabio Bevilacqua & Enrico Giannetto (eds.), Volta and the History of Electricity, Pavia / Milano, Università degli Studi di Pavia / Editore Ulrico Hoepli, 2003, pp. 245-265. (Collana di Storia della Scienza) ISBN:88-203-3284-1

- ↑ Fahie, p. 273

- ↑ See:

- Örsted, Johannis Christianis (1820) (in la). Experimenta circa effectum conflictus electrici in acum magneticam. Copenhagen, Denmark: (Self-published). https://archive.org/details/Experimentacirc00Orst/page/n3/mode/2up.

- Reprinted in English in: Oersted, John Christian (1820). "Experiments on the effect of a current of electricity on the magnetic needle". Annals of Philosophy 16: 273–276. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=osu.32435051156651&view=1up&seq=297.

- ↑ Fahie, John Joseph, A History of Electric Telegraphy, to the Year 1837, London: E. & F.N. Spon, 1884 OCLC 559318239, pp. 302–303.

- ↑ "APS Member History". https://search.amphilsoc.org/memhist/search?year=1829;year-max=1829;smode=advanced;f1-date=1829.

- ↑ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter O". American Academy of Arts and Sciences. http://www.amacad.org/publications/BookofMembers/ChapterO.pdf.

- ↑ "History of DTU". Technical University of Denmark. http://www.dtu.dk/English/About_DTU/History_of_DTU.aspx.

- ↑ Örsted, H.C. (1824). "[No title"] (in da). Oversigt over Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskabs Forhanlingar og Dets Medlemmerz Arbeider, Fra 31 Mai 1824 Til 31 Mai 1825 (Overview of the Royal Danish Science Society's Proceedings and the Work of Its Members, from 31 May 1824 to 31 May 1825): 15–16. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=osu.32435054254693&view=1up&seq=17.

- ↑ Kvande, Halvor (25 October 2008). "Two hundred years of aluminum ... or is it aluminium?". JOM 60 (8): 23–24. doi:10.1007/s11837-008-0102-3. Bibcode: 2008JOM....60h..23K.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Aluminum Discovery and Extraction – A Brief History". http://www.aluminum-production.com/aluminum_history.html.

- ↑ "ALUMINIUM HISTORY". UC RUSAL. https://www.aluminiumleader.com/history/industry_history/.

- ↑ Juan de Pablo

- ↑ The H.C. Ørsted Lectures

- ↑ National Museum of Denmark. "The Soul in Nature: 1802 ". Accessed 30 July 2007.

- ↑ Hans Christian, Ørsted (1852). The soul in nature: with supplementary contributions. H. G. Bohn. https://archive.org/details/soulinnaturewit00rsgoog. "The soul in nature."

Further reading

- Brain, R. M. (2007). Hans Christian Ørsted and the Romantic Legacy in Science. Ideas, Disciplines, Practices. Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, 241. Dordrecht. pp. 273–338.

- Christensen, D. C. (2013). Hans Christian Ørsted. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-966926-4.

- Bern Dibner (1962) Oersted and the discovery of electromagnetism, New York, Blaisdell.

- Ole Immanuel Franksen (1981) H. C. Ørsted – a man of the two cultures, Strandbergs Forlag, Birkerød, Denmark. (Note: Both the original Latin version and the English translation of his 1820 paper "Experiments on the effect of a current of electricity on the magnetic needle" can be found in this book.)

- Hans Christian Ørsted (1997). Karen Jelved, Andrew D. Jackson, and Ole Knudsen, translators from Danish to English. Selected Scientific Works of Hans Christian Ørsted, ISBN:0-691-04334-5.

External links

Media related to Hans Christian Ørsted at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hans Christian Ørsted at Wikimedia Commons- Physics Tree: Hans Christian Ørsted Details

- Interactive Java Tutorial on Oersted's Compass Experiment National High Magnetic Field Laboratory

- The soul in nature : with supplementary contributions, London: H. G. Bohn, 1852.

- Hans Christian Ørsted at Find a Grave

"Oersted, Hans Christian". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

"Oersted, Hans Christian". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

|

Categories: [Discoverers of chemical elements] [Magneticians] [Aluminium]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 03/26/2023 12:55:00 | 1 views

☰ Source: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Biography:Hans_Christian_Ørsted | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF