Paul-Henri Spaak

From Nwe

From Nwe

| Paul-Henri Spaak | |

|

|

|

Prime Minister of Belgium

|

|

| In office May 15 1938 – February 22 1939 |

|

| Preceded by | Paul-Émile Janson |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | Hubert Pierlot |

| In office March 13 1946 – March 31 1946 |

|

| Preceded by | Achille van Acker |

| Succeeded by | Achille van Acker |

| In office March 20 1947 – 11 August 1949 |

|

| Preceded by | Camille Huysmans |

| Succeeded by | Gaston Eyskens |

|

President of the United Nations General Assembly

|

|

| In office 1946 – 1947 |

|

| Preceded by | post created |

| Succeeded by | Oswaldo Aranha |

|

President of the Common Assembly of the European Coal Steel Community

|

|

| In office 1952 – 1954 |

|

| Preceded by | post created |

| Succeeded by | Alcide De Gasperi |

|

2nd Secretary General of NATO

|

|

| In office 1957 – 1961 |

|

| Preceded by | Hastings Ismay, 1st Baron Ismay |

| Succeeded by | Dirk Stikker |

|

|

|

| Born | 25 January 1899 Schaerbeek, Belgium |

| Died | 31 July 1972 (aged 73) Braine-l'Alleud, Belgium |

| Political party | Belgian Socialist Party |

| Spouse | Marguerite Malevez Simone Dear |

Paul-Henri Charles Spaak (January 25, 1899 - July 31, 1972) was a Belgian Socialist politician and statesman. He became a member of parliament in 1932 and a member of the cabinet in 1935. He served three times as Foreign Minister (1938-1939, 1939-1949 and 1954-1958) interspersed with three terms as Prime Minister, 1938-1939, in March 1946 and from 1947-1949. Internationally, he served as the first President of the United Nations General Assembly, President of the Council of Europe's Parliamentary Assembly (1949-1951), President of the European Coal and Steel Community (1961), Secretary-General of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (1957) and was instrumental in making Brussels the Alliance's headquarters.

Spaak's commitment to European integration and cooperation in the post-World War II space earned him wide respect. In 1961 he was honored by the United States with the Presidential Medal of Freedom. With Robert Schuman, Jean Monnet, Alcide De Gasperi, and Konrad Adenauer Spaak is widely acknowledged as one of the main architects of the new European space after World War II. Spaak's legacy lives on in the institutions he helped to create and in the commitment of his political heirs in Europe to make war unthinkable and materially impossible. His conviction that nations need to sacrifice self-interest in order for all people of the world to flourish remains relevant, as does his dream of a more unified world. Spaak served his own nation with distinction and, situating himself within the wider world, he also served humanity.

Llife

Paul-Henri Spaak was born in Schaerbeek to Paul Spaak and Marie Janson. His mother - the daughter of Paul Janson and sister to Paul-Émile Janson, both Liberal politicians - was the country's first female Senator.

During World War I, Spaak lied about his age to be accepted in the Army; he subsequently spent two years as a German prisoner of war.

Spaak studied law at the Free University of Brussels (now split into the Université Libre de Bruxelles and the Vrije Universiteit Brussel).

Spaak married Marguerite Malevez and they had two daughters—Antoinette Spaak led the Democratic Front of Francophones—and a son, the diplomat Fernand Spaak. After her death in August 1964, he married Simone Dear in April 1965. His niece was the actress Catherine Spaak. During the 1940s, during his time in New York with the United Nations, he also had an affair with the American fashion designer Pauline Fairfax Potter (1908-1976).

Spaak died aged 73, on 31 July 1972 in his home in Braine-l'Alleud near Brussels, and was buried at the Foriest graveyard in Braine-l'Alleud.

Political career

Spaak became a member of the Socialist Belgian Labor Party in 1920. He was elected deputy in 1932.

In 1935 he entered the cabinet of Paul Van Zeeland as Minister of Transport. In February 1936 he became Minister of Foreign Affairs, serving first under Zeeland and then under his uncle, Paul-Émile Janson. From May 1938 to February 1939 he was Prime Minister for the first time.

He was Foreign Minister again from September 1939 until August 1949 under the subsequent Prime Ministers Hubert Pierlot, Achille Van Acker and Camille Huysmans. During this time he twice was appointed Prime Minister as well, first from 13 to 31 March 1946 - the shortest government in Belgian history, and again from March 1947 to August 1949.

He again was foreign minister from April 1954 to June 1958 in the cabinet of Achille Van Acker and from April 1961 to March 1966 in the cabinets of Théo Lefèvre and Pierre Harmel.

Spaak was an advocate of Belgium's historical policy of neutrality before World War II. During the German invasion in May 1940, he fled to France and tried to return during the summer but was prevented by the Germans, even he was Foreign Minister as the time. Against his wishes he settled in Britain until the war ended when he became Foreign Minister again "from the Liberation until the middle of 1949."[1]

United Nations

Spaak gained international prominence in 1945, when he was elected chairman of the first session of the General Assembly of the United Nations. During the third session of the UN General Assembly in Paris, Spaak apostrophized the delegation of the Soviet Union with the famous words: "Messieurs, nous avons peur de vous" (Sirs, we are afraid of you).

Europe

Spaak became a staunch supporter of regional cooperation and collective security after 1944. According to Lipgens, his interest in unification dated back to the 1920s but he stopped speaking about the idea of European Union once the Nazism had "commandeered the idea".[1] While still in exile in London, he promoted the creation of a customs union uniting Belgium, The Netherlands and Luxembourg (see Benelux). In August 1946, he was elected chairman of the first session of the consultative Assembly of the Council of Europe. From 1952 to 1953, he presided the General Assembly of the European Coal and Steel Community. In fact, until 1948 he was an enthusiastic supported of "one world" but focused on European integration when he realized that the Cold War but this dream on hold.[1] He wrote in a 1965 article about his hope that "that we had made some progress on the road which some day, however distant, would lead to the unity of nations."[2]

With his fellow founders of the new European instruments, he believed that the time had come for nations to voluntarily relinquish some of their sovereignty;

We know that in order to "make Europe" many obstacles have to be surmounted, and we also know ... that making Europe involves some sacrifices. Those who believe that the European organization of tomorrow is a system in which every country will enjoy the advantages it had yesterday and also a few more, and that the same will be true of every class in each country, and every individual ... are mistaken.[1]

He went on to explain that one of the most important sacrifices was that nations would need to sacrifice even what they saw as "legitimate self interest" so that the "whole European community to which we belong will find in the new system greater prosperity, greater happiness and well-being."

He also spoke about the "European mind" that found expression in a "common sense of purpose" and of how the new Europe was based on shared Values; "our ideas on political, social and legal matters are very nearly the same" and our "living standards are becoming more and more alike."[1] Europe would, he said, never again surrender the principle that had been won of "tolerance and freedom, political democracy" nor the "moral principles" that Europeans "all have in common."[1]

He was a strong supporter of the Marshall Plan and of the need for partnership with North America to preserve world peace. He said that,

"Thanks to the Marshall Plan, the economy of the democratic part of Europe was saved....The aims defined by General Marshall in his Harvard speech were attained. The success was a striking demonstration of the advantages of cooperation between the United States and Europe, as well as among the countries of Europe themselves.[3]

He believed that "uniting countries through binding Treaty obligations were the most effective means of guaranteeing peace and stability."[4]

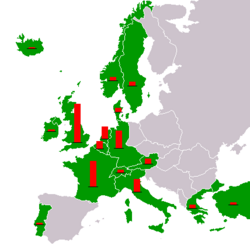

In 1955, the Messina Conference of European leaders appointed him as chairman of a preparatory committee (Spaak Committee) charged with the preparation of a report on the creation of a common European market.[5] The so-called "…Spaak Report formed the cornerstone of the Intergovernmental Conference on the Common Market and Euratom at Val Duchesse in 1956 and led to the signature, on 25 March 1957, of the Treaties of Rome establishing a European Economic Community and the European Atomic Energy Community (Euratom). Paul-Henri Spaak signed the treaty for Belgium, together with Jean Charles Snoy et d'Oppuers. His role in the creation of the EEC earned Spaak a place among the Founding fathers of the European Union.

NATO

In 1956, he was chosen by the Council of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization to succeed Lord Ismay as Secretary General. He held this office from 1957 until 1961, when he was succeeded by Dirk Stikker. Spaak was also instrumental in the choice of Brussels as the new seat of the Alliance's HQ in 1966.

This was also the year of his last European campaign, when he played an important conciliatory role in resolving the "empty chair crisis" by helping to bring France back into the European fold.[6]

Retirement

Spaak retired from politics in 1966.

He was a member of the Royal Belgian Academy of French Language and Literature. In 1969, he published his memoirs in two volumes titled Combats inachevés ("The Continuing Battle").

Legacy

With Robert Schuman, Jean Monnet, Alcide De Gasperi, and Konrad Adenauer, Spaak is widely acknowledged as one of the main architects of the new European space after World War II. Spaak's legacy lives on in the institutions he helped to create, which include the United Nations and the European Union. His legacy continues to inspire his political heirs in Europe to make war unthinkable and materially impossible. His conviction that nations need to sacrifice self-interest in order for all people of the world to flourish remains relevant. It points the way forward towards achieving his dream of a unified world. Biographer Johan Huizinga describes him as "Mr Europe."

Spaak served his own nation with distinction but situated himself within the wider world and also served humanity. His legacy also continues in Belgium's own commitment to remaining at the heart of the new Europe; "Belgium considers Brussels to be the 'heart of Europe'" says Hagendoorn.[7]

Honors

In 1957 Spaak received the Karlspreis (Charlemagne Award) an Award by the German city of Aachen to people who contributed to the European idea and European peace.

On February 21, 1961 he was awarded the Medal of Freedom by John F. Kennedy.

In 1973, the Foundation Paul-Henri Spaak was created to perpetuate his work in the field of European integration and Atlantic relations. His personal papers deposited at the Historical Archives of the European Union in 2003.

In 1981, the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs at Harvard University named the annual Paul-Henri Spaak in his honor.[8] The Center also offers the Paul-Henri Spaak Post-Doctoral Research Fellowship in U.S.-European Relations. The Fund for Scientific Research – Flander offers a Paul-Henry Spaak PhD scholarship.

Spaak was featured on one of the most recent and famous gold commemorative coins: the Belgian 3 pioneers of the European unification commemorative coin, minted in 2002. The obverse side shows a portrait with the names Robert Schuman, Paul-Henri Spaak, and Konrad Adenauer.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Walter Lipgens and Wilfried Loth, Documents on the history of European integration. Vol. 3, The struggle for European union by political parties and pressure groups in Western European countries 1945-1950 (Berlin, DE: De Gruyter, 1988, ISBN 978-3110114294), 330-332.

- ↑ Paul-Henri Spaak, "The Search for Consensus: A New Effort to Build Europe" Foreign Affairs. 43(2) (1965):199–208.

- ↑ Michael J. Hogan, Blueprint for Recovery The Marshall Plan: Investment for Peace. United States Department of State International Information Programs. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- ↑ Paul–Henri Spaak: a European visionary and talented persuader Europea: the History of the European Union. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- ↑ Andrew Knapp and Vincent Wright, The government and politics of France (London, UK: New York, 2006, ISBN 978-0415357326), 424.

- ↑ Trevor C. Salmon and William Nicoll, Building European Union: a documentary history and analysis (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0719044458), 91.

- ↑ Louk Hagendoorn et. al., European Nations and Nationalism: Theoretical and Historical Perspectives (Routledge, 2000, ISBN 978-0754611363), 124.

- ↑ Paul-Henri Spaak Lecture Series. Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, Harvard University. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dumoulin, Michel. Spaak. Bruxelles, BE: Racine, 1999. ISBN 978-2873861629. (French)

- Hagendoorn, Louk, György Csepeli, and Russell Farnen. European Nations and Nationalism: Theoretical and Historical Perspectives. Routledge, 2000. ISBN 978-0754611363

- Huizinga, J.H. Mr. Europe: A Political Biography of Paul-Henri Spaak. New York, NY: Praeger, 1961. OCLC 4119128

- Knapp, Andrew, and Vincent Wright. The government and politics of France. London, UK: New York, 2006. ISBN 978-0415357326.

- Lipgens, Walter, and Wilfried Loth. Documents on the history of European integration. Vol. 3, The struggle for European union by political parties and pressure groups in Western European countries 1945-1950: (including 252 documents in their original languages on 6 microfiches). Berlin, DE: De Gruyter, 1988. ISBN 978-3110114294.

- Salmon, Trevor C., and William Nicoll. Building European Union: a documentary history and analysis. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0719044458.

- Spaak, Paul-Henri. The continuing battle: memoirs of a European, 1936-1966. London, UK: Weidenfeld, 1971. ISBN 978-0297993520.

- Spaak, Paul-Henri, and Andrew Moravcsik. Europe without illusions: the Paul-Henri Spaak lectures, 1994-1999. Paul-Henri Spaack lectures. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2005. ISBN 978-0761831280.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 21:39:55 | 1 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Paul-Henri_Spaak | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed: KSF

KSF