Gastrointestinal Tract

From Nwe

From Nwe The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract), also called the digestive tract, alimentary canal or gut, is the system of organs within multicellular animals that takes in water and food, extracts energy and nutrients from the food, and expels the remainder as waste. The major functions of the GI tract are digestion and excretion.

Digestion refers to the process of metabolism whereby a biological entity applies both mechanical and chemical procedures to reduce a substance to component parts that are then absorbed into the body and distributed throughout via the circulatory system (Silverthorn 2004). Excretion is the process of eliminating the waste products of metabolism and other non-useful materials.

The digestive process involves the cooperative work of many body components, including the heart, brain, liver, and pancreas. For example, the heart directs blood to the area and the liver and pancreas secrete digestive enzymes. The process also reflects individuality. For instance, some individuals can digest milk or eat peanuts, while others may have an allergy to one or both of these, and people enjoy different tastes.

The GI tract differs substantially from animal to animal. For instance, some animals have multi-chambered stomachs, while some animals' stomachs contain a single chamber. In a normal human adult male, the GI tract is approximately 6.5 meters (20 feet) long and consists of the upper and lower GI tracts. The tract may also be divided into foregut, midgut, and hindgut, reflecting the embryological origin of each segment of the tract.

Gastrointestinal tract in humans

In humans, the gastrointestinal tract is a long tube with muscular walls comprising four different layers: inner mucosa, submucosa, muscularis externa, and the serosa (see histology section). It is the contraction of the various types of muscles in the tract that propel the food.

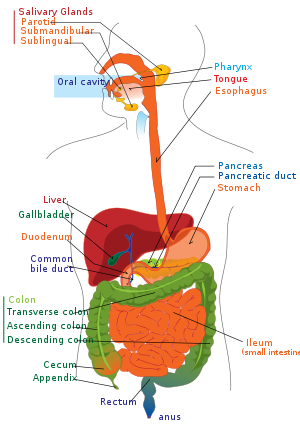

The GI tract can be divided into an upper and a lower tract. The upper GI tract consists of the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, and stomach. The lower GI tract is made up of the intestines and the anus.

Upper gastrointestinal tract

The upper GI tract consists of the mouth, pharynx, esophagus, and stomach.

- The mouth comprises the oral mucosa, buccal mucosa, tongue, teeth, and openings of the salivary glands. The mouth is the point of entry of the food into the GI tract and the site where digestion begins as food is broken down and moistened in preparation for further transit through the GI tract.

- Behind the mouth lies the pharynx, which leads to a hollow muscular tube called the esophagus or gullet. In an adult human, the esophagus (also spelled oesphagus) is about one inch in diameter and can range in length from 10-14 inches (NR 2007).

- Food is propelled down through the esophagus to the stomach by the mechanism of peristalsis—coordinated periodic contractions of muscles in the wall of the esophagus. The esophagus extends through the chest and pierces the diaphragm to reach the stomach, which can hold between 2-3 liters of material in an adult human. Food typically remains in the stomach for two to three hours.

- The stomach, in turn, leads to the small intestine.

The upper GI tract roughly corresponds to the derivatives of the foregut, with the exception of the first part of the duodenum (see below for more details.)

Lower gastrointestinal tract

The lower GI tract comprises the intestines and anus.

- Bowel or intestine

- The small intestine, approximately 7 meters (23 feet) feet long and 3.8 centimeters (1.5 inches) in diameter, has three parts (duodenum, jejunum, and ileum). It is where most digestion takes place. Accessory organs, such as the liver and pancreas help the small intestine digest, and more importantly, absorb important nutrients needed by the body. Digestion is for the most part completed in the small intestine, and whatever remains of the bolus have not been digested are passed onto the large intestine for final absorption and excretion.

- duodenum – the first 25 centimeters (9.84 inches)

- jejunum and ileum – combined are approximately 6 meters (19.7 feet) in length

- The large intestine – (about 1.5 meters (5 feet) long with a diameter of about 9 centimeters (3.5 inches) also has three parts:

- cecum (the appendix is attached to the cecum)

- The colon (ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon and sigmoid flexure) is where feces are formed after absorption is completed

- The rectum propels feces to the final part of the GI tract, the anus

- The small intestine, approximately 7 meters (23 feet) feet long and 3.8 centimeters (1.5 inches) in diameter, has three parts (duodenum, jejunum, and ileum). It is where most digestion takes place. Accessory organs, such as the liver and pancreas help the small intestine digest, and more importantly, absorb important nutrients needed by the body. Digestion is for the most part completed in the small intestine, and whatever remains of the bolus have not been digested are passed onto the large intestine for final absorption and excretion.

- The anus, which is under voluntary control, releases waste from the body through the defecation process

Related organs

Accessory organs to the GI tract help in digestion by releasing powerful enzymes and other fluids that breakdown macromacules into smaller molecules that can be absorbed by the digestive system. Two such organs are the liver and pancreas.

The liver secretes bile into the small intestine via the biliary system, employing the gall bladder as a reservoir. Apart from storing and concentrating bile, the gall bladder has no other specific function. The pancreas secretes an isosmotic fluid containing bicarbonate and several enzymes, including trypsin, chymotrypsin, lipase, pancreatic amylase, and nucleolytic enzymes (deoxyribonuclease and ribonuclease), into the small intestine.

Embryology

The human embryo has three germ layers: endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm. These layers differentiate and give rise to various structures.

The gut is an endoderm-derived structure. At approximately the sixteenth day of human development, the embryo begins to fold ventrally (with the embryo's ventral surface becoming concave) in two directions: the sides of the embryo fold in on each other and the head and tail fold towards one another. The result is that a piece of the yolk sac, an endoderm-lined structure in contact with the ventral aspect of the embryo, begins to be pinched off to become the primitive gut. The yolk sac remains connected to the gut tube via the vitelline duct. Usually this structure regresses during development; in cases where it does not, it is known as Meckel's diverticulum.

During fetal life, the primitive gut can be divided into three segments: foregut, midgut, and hindgut. Although these terms are often used in reference to segments of the primitive gut, they are nevertheless used regularly to describe components of the definitive gut as well.

Each segment of the primitive gut gives rise to specific gut and gut-related structures in the adult. Components derived from the gut proper, including the stomach and colon, develop as swellings, or dilatations, of the primitive gut. In contrast, gut-related derivatives (those structures that derive from the primitive gut but are not part of the gut proper) in general develop as outpouchings of the primitive gut. The blood vessels supplying these structures remain constant throughout development (Carlson 2004).

| Part | Range in adult | Gives rise to | Arterial supply |

| foregut | the pharynx, to the upper duodenum | pharynx, esophagus, stomach, upper duodenum, respiratory tract (including the lungs), liver, gallbladder, and pancreas | branches of the celiac artery |

| midgut | lower duodenum, to the first half of the transverse colon | lower duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, appendix, ascending colon, and first half of the transverse colon | branches of the superior mesenteric artery |

| hindgut | second half of the transverse colon, to the upper part of the anal canal | remaining half of the transverse colon, descending colon, rectum, and upper part of the anal canal | branches of the inferior mesenteric artery |

Physiology

Specialization of organs

Four organs are subject to specialization in the kingdom Animalia.

- The first organ is the tongue, which is only present in the phylum Chordata.

- The second organ is the esophagus. The crop is an enlargement of the esophagus in birds, insects, and other invertebrates that is used to store food temporarily.

- The third organ is the stomach. In addition to a glandular stomach (proventriculus), birds have a muscular "stomach" called the ventriculus, or "gizzard." The gizzard is used to mechanically grind up food.

- The fourth organ is the large intestine. An outpouching of the large intestine called the cecum is present in non-ruminant herbivores such as rabbits. It aids in digestion of plant material such as cellulose.

Immune function

The gastrointestinal tract is also a prominent part of the immune system (Coico et al. 2003). The low pH (ranging from 1 to 4) of the stomach is fatal for many microorganisms that enter it. Similarly, mucus (containing IgA antibodies) neutralizes many of these microorganisms. Other factors in the GI tract help with immune function as well, including enzymes in the saliva and bile. Enzymes such as Cyp3A4, along with the antiporter activities, are also instrumental in the intestine's role of detoxification of antigens and xenobiotics, such as drugs, involved in first pass metabolism. Health-enhancing intestinal bacteria serve to prevent the overgrowth of potentially harmful bacteria in the gut. Microorganisms are also kept at bay by an extensive immune system comprising the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT).

Histology

The GI tract has a uniform general histology with some differences which reflect the specialization in functional anatomy (Kierszenbaum 2002).

The GI tract can be divided into 4 concentric layers:

- mucosa

- submucosa

- muscularis externa (the external muscle layer)

- adventitia or serosa

Mucosa

The mucosa is the innermost layer of the GI tract, surrounding the lumen, or space within the tube where digestion mainly takes place. This layer comes in direct contact with the food (or bolus), and is responsible for absorption and secretion, both of which are important processes in digestion.

The mucosa can be divided into:

- epithelium

- lamina propria (connective tissue that keeps the epithelium steady)

- muscularis mucosae (thin layer of smooth muscle)

The mucosae are highly specialized in each organ of the GI tract, facing a low pH in the stomach, absorbing a multitude of different substances in the small intestine, and also absorbing specific quantities of water in the large intestine. Reflecting the varying needs of these organs, the structure of the mucosa can consist of invaginations of secretory glands (e.g., gastric pits), or it can be folded in order to increase surface area (examples include villi and plicae circulares).

Submucosa

The submucosa consists of a dense irregular layer of connective tissue with large blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves branching into the mucosa and muscularis. It contains Meissner's plexus, an enteric nervous plexus, situated on the inner surface of the muscularis externa. This network of nerves connects the outer smooth muscles to the innermost mucous membranes in the stomach and small intestines. The function of the plexus is not completely known.

Muscularis externa

The muscularis externa consists of a circular inner muscular layer and a longitudinal outer muscular layer. The circular muscle layer prevents the food from going backwards and the longitudinal layer shortens the tract. The coordinated contractions of these layers is called peristalsis and propels the bolus, or balled-up food, through the GI tract.

Between the two muscle layers are the myenteric or Auerbach's plexus.

Adventitia/Serosa

The adventitia consists of several layers of epithelia. The serosa covers the entire GI tract, which helps to keep the intestines from tangling as they contract and move. The serosa is part of the membrane that lines the abdominal cavity (peritoneum). The mesentery, also part of the peritoneal membrane, helps the serosa keep the intestines in place.

Human uses of animal gut

- The use of animal gut strings by musicians can be traced back to the third dynasty of Egypt. In the recent past, strings were made out of lamb gut. With the advent of the modern era, musicians have tended to use synthetic strings made of nylon, silk, or steel. Some instrumentalists, however, still use gut strings in order to evoke the older tone quality. Although such strings were commonly referred to as "catgut" strings, cats were never used as a source for gut strings.

- Sheep gut was the original source for natural gut string used in racquets, such as for tennis. Today, synthetic strings are much more common, but the best strings are now made out of cow gut.

- Gut cord has also been used to produce strings for the snares which provide the snare drum's characteristic buzzing timbre. While the snare drum currently almost always uses metal wire rather than gut cord, the North African bendir frame drum still uses gut for this purpose.

- "Natural" sausage hulls (or casings) are made of animal gut, especially hog, beef, and lamb.

- Animal gut was used to make the cord lines in longcase clocks, but may be replaced by the wire.

- The oldest condoms found were made from animal intestine.

See also

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carlson, B. M. 2004. Human Embryology and Developmental Biology, 3rd edition. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 032303649X

- Coico, R., G. Sunshine, and E. Benjamini. 2003. Immunology: A Short Course. New York: Wiley-Liss. ISBN 0471226890

- Kierszenbaum, A. L. 2002. Histology and Cell Biology: An Introduction to Pathology. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 0323016391

- Nexium Research (NR). 2007. Digestive System. Nexiumresearch.com. Retrieved Nov. 10, 2007.

- Silverthorn, D. 2004. Human Physiology: An Integrated Approach, 3rd ed. Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 0131020153

External links

All links retrieved May 23, 2017.

| Digestive system - edit |

|---|

| Mouth | Pharynx | Esophagus | Stomach | Pancreas | Gallbladder | Liver | Small intestine (duodenum, jejunum, ileum) | Colon | Cecum | Rectum | Anus |

| Human organ systems |

|---|

| Cardiovascular system | Digestive system | Endocrine system | Immune system | Integumentary system | Lymphatic system | Muscular system | Nervous system | Skeletal system | Reproductive system | Respiratory system | Urinary system |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 22:24:32 | 117 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Gastrointestinal_tract | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF