Ayurveda

From Nwe

From Nwe Ayurveda (Devanāgarī: आयुर्वॆद, the 'science of life') is a system of traditional medicine native to India, and practiced in other parts of the world as a form of alternative medicine. In Sanskrit, the word Ayurveda comprises the words āyus, meaning 'life' and veda, meaning 'science.'[1] Evolving throughout its history, Ayurveda remains an influential system of medicine in South Asia. The earliest literature of Ayurveda appeared during the Vedic period in India. The Sushruta Samhita and the Charaka Samhita were influential works on traditional medicine during this era. Ayurvedic practitioners also identified a number of medicinal preparations and surgical procedures for curing various ailments and diseases.

Ayurveda has become an alternative form of medicine in the western world, where patents for its medicine have been passed, and the intellectual property rights contested by Western and Indian institutions.[2]

Origins

Ayurveda traces its origins to the Vedas—the Atharvaveda in particular—and is connected to religion and mythology.[9] The Sushruta Samhita of Sushruta appeared during the first millennium B.C.E. on the work of the surgeon Sushruta:

The original text is believed to have 5 books and 120 chapters. The text in its current form contains details of around 1120 medical conditions, 700 medicinal plants, 400 surgeries and 121 surgical instruments.[10]

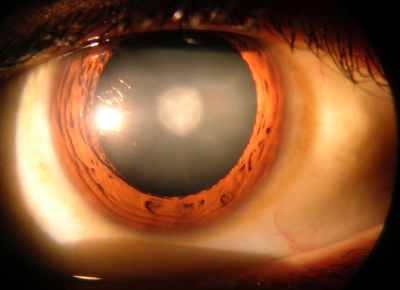

This early phase of traditional Indian medicine identified fever (takman), cough, consumption, diarrhea, dropsy, abscesses, seizures, tumors, and skin diseases (including leprosy).[11]Treatment of complex ailments—including Angina pectoris, diabetes, hypertension, and stones—also ensued during this period.[12] Plastic surgery, cataract surgery, puncturing to release fluids in the abdomen, extraction of foreign elements, treatment of anal fistulas, treating fractures, amputations, cesarean sections, and stitching of wounds were known. The use of herbs and surgical instruments became widespread.[11]

Other early works of Ayurveda include the Charaka Samhita, attributed to Charaka.[11] The earliest surviving excavated written material which contains the works of Sushruta is the Bower Manuscript—dated to the fourth century C.E.[13] The Bower manuscript cites directly from Sushruta, and is of special interest to historians due to the presence of Indian medicine and its concepts in Central Asia.[14] Vagbhata—the son of a senior doctor by the name of Simhagupta—[15] also compiled his works on traditional medicine. Early Ayurveda had a school of physicians and a school of surgeons.[16] Tradition holds that the text Agnivesh tantra—written by the legendary sage Agnivesh, a student of the mythological sage Bharadwaja—influenced the writings of Ayurveda.[17]

The Chinese pilgrim Fa Hsien (ca. 337 - 422 C.E.) wrote about the health care system of the Gupta empire (320 - 550 C.E.) and—in process—described the institutional approach of Indian medicine which is also visible in the works of Caraka, who mentions a clinic and how it should be equipped.[18] Madhava (700 C.E.), Sarngadhara (1300 C.E.), and Bhavamisra (1500 C.E.) compiled works on Indian medicine.[14] The medical works of both Sushruta and Charaka were translated into Arabic language during the Abbasid Caliphate (750 C.E.). These Arabic works made their way into Europe via intermediaries. In Italy the Branca family of Sicily and Gaspare Tagliacozzi (Bologna) became familiar with the techniques of Sushruta.[19]

British physicians traveled to India to see Rhinoplasty being performed by native methods. Reports on Indian Rhinoplasty were published in the Gentleman's Magazine by 1794.[20] Joseph Constantine Carpue spent 20 years in India studying local plastic surgery methods. Carpue was able to perform the first major surgery in the Western world by 1815. Instruments described in the Sushruta Samhita were further modified in the Western World.[21]

Description

Ayurveda believes in 'five great elements' (Devanāgarī: पन्छतत्व; earth, water, fire, air and space) forming the universe, including the human body.[1] Blood, flesh, fat, bone, marrow, chyle, and semen are the seven primary constituent elements (Devanāgarī: सप्तधातु) of the body.[11] Ayurveda stresses a balance of three substances: wind/spirit/air, phlegm, and bile, each representing divine forces. The doctrine of these three Dosas (Devanāgarī: त्रिदॊश्)—vata (wind/spirit/air), pitta (bile) and kapha (phlegm)—is important. Traditional beliefs hold that humans possess a unique constellation of Dosas.[22] In Ayurveda, the human body has 20 Guna (Devanāgarī: गुन, meaning quality).[23] Surgery and surgical instruments are employed. It is believed that building a healthy metabolic system, attaining good digestion, and proper excretion leads to vitality.[23] Ayurveda also focuses on exercise, yoga, meditation, and massage.

The concept of Panchakarma (Devanāgarī: पन्छ्कर्म) is believed to eliminate toxic elements from the body.[24] Eight disciplines of Ayurveda treatment, called Ashtanga (Devanāgarī: अश्ताग्), are given below:[25]

- Surgery (Shalya-chkitsa).

- Treatment of diseases above the clavicle (Salakyam).

- Internal medicine (Kaya-chikitsa).

- Demonic possession (Bhuta vidya): Ayurveda believes in demonic intervention and—as a form of traditional medicine—identifies a number of ways to counter the supposed effect of these interferences.[26] Bhuta vidya has been called psychiatry.[16]

- Pediatrics (Kaumarabhrtyam).

- Toxicology (Agadatantram).

- Prevention and building immunity (rasayanam).

- Aphrodisiacs (Vajikaranam).

Practices

Buddhism may have been an influence on the development of many of Ayurveda's central ideas—particularly its fascination with balance, known in Buddhism as Madhyamika (Devanāgarī: मद्यमिका). Balance is emphasized and suppressing natural urges is seen to be unhealthy and doing so may almost certainly lead to illness. To stay within the limits of reasonable balance and measure is stressed upon.[27] Ayurveda emphasizes on moderation in food intake, sleep, sexual intercourse, and the intake of medicine.[27]

Ayurveda incorporates an entire system of dietary recommendations:

Ayurvedic dietetics comprise a host of recommendations, ranging from preparation and consumption of food, to healthy routines for day and night, sexual life, and rules for ethical conduct. In contrast to contemporary practitioners of New Age Ayurveda, older Ayurvedic authors tended to be religiously neutral. Even Buddhist authors refrained from trying to convert the patient to follow their particular religious ways.[28]

For diagnosis the patient is to be questioned and all five senses are to be employed. The Charaka Samhita recommends a tenfold examination of the patient. The qualities to be judged are: constitution, abnormality, essence, stability, body measurements, diet suitability, psychic strength, digestive capacity, physical fitness and age.[29] Hearing is used to observe the condition of breathing and speech.[11] The study of the vital pressure points or marma is of special importance.[23]

Chopra (2003) identifies five influential criteria for diagnosis: 'origin of the disease, prodrominal (precursory) symptoms, typical symptoms of the fully developed disease, observing the effect of therapeutic procedures, and the pathological process.'[29]

Hygiene—also a component of religious virtue to many Indians—is a strong belief. Hygienic living involves regular bathing, cleansing of teeth, skin care, and eye washing. Occasional anointing of the body with oil is also prescribed.[11]

Ayurveda stresses on vegetable drugs. Fats are used both for consumption and for external use. Hundreds of vegetable drugs are employed, including cardamom and cinnamon. Some animal products may also be used, for example milk, bones, and gallstones, etc. Minerals—including sulfur, arsenic, lead, copper sulfate, and gold—are also consumed as prescribed.[11]

Alcohol is used as a narcotic for the patient undergoing operation in some cases.[11] The advent of Islam introduced opium as a narcotic.[25] Both oil and tar are used to stop bleeding.[11] Oils may be used in a number of ways including regular consumption as a part of food, anointing, smearing, head massage, and prescribed application to infected areas.[30]

The proper function of channels—tubes that exist within the body and transport fluids from one point to another—is seen as vital, and the lack of healthy channels may lead to disease and insanity. Sushruta identifies that blockages of these channels may lead to rheumatism, epilepsy, paralysis, and convulsions as fluids and channels are diverted from their ideal locations. Sweating is favored as a manner in which to open up the channels and dilute the Doshas causing the blockages and harming a patient—a number of ways to take steam bathing and other steam related cures are recommended so that these toxins are released.[31]

Current Status

Within South Asia

In 1970, the Indian Medical Central Council Act was passed by the Parliament of India, which aims to standardize qualifications for Ayurveda and provide accredited institutions for its study and research.[32] In India, over 100 colleges offer degrees in traditional Ayurvedic medicine. Indian Government supports research and teaching in Ayurveda through many channels—both at the national and state levels—and helps institutionalize traditional medicine so that it can be studied in major towns and cities.[33] The state-sponsored Central Council for Research in Ayurveda and Siddha (CCRAS) is the apex institution for promotion of traditional medicine in India. The studies conducted by this institution encompass clinical, drug, literary, and family welfare research.[34]

Many successful clinics are run by professionals who qualify from these institutes—both in the urban and the rural areas.[32] Mukherjee and Wahile cite World Health Organization statistics to demonstrate the popularity of traditional medicine, on which a significant number of the world's population depends for primary health care.[35] The manufacture and marketing of Ayurvedic medicine has been commercially successful for several pharmaceutical companies.[32]

Outside India

Ayurveda practitioners require a license in another stream of health care in the United States of America. Academic institutions related to traditional medicine in India have contributed to Ayurveda's international visibility. Kurup (2003) comments on the role of Gujarat Ayurved University:

"The Gujarat Ayurved University has signed the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with nine Ayurvedic institutes functioning in Japan, Australia, the Netherlands, Italy, Argentina, and Germany to coordinate and facilitate the globalization of Ayurveda through academic collaboration. Earlier, Medical (Ayu) Institute of Russia had signed the MoU with the Government of India, in which Gujarat Aryurved University is also one of the implementing authorities."[36]

Ayurveda gained recognition in the Western world as medical scholars researched and outlined its various postulates.[37] In the United States of America, the NIH NCCAM spends some of its budget on Ayurvedic medicine research. In addition, the National Institute of Ayurvedic Medicine (NIAM), established by Dr. Scott Gerson, is an example of a research institute that has carried out research into Ayurvedic practices.[38]

Patents

In December 1993, the University of Mississippi Medical Center had a patent issued to them by United States Patent and Trademark Office on the use of turmeric for healing.[39] The patent was contested by India's industrial research organization, Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (C.S.I.R), on the grounds that traditional Ayurvedic practitioners were already aware of the healing properties of the substance and have been for centuries, making this patent a case of bio-piracy. To fight biopiracy and unethical patents, in 2001 the government of India set up the Traditional Knowledge Digital Library as a repository for formulations of various systems of Indian medicine, such as Ayurveda, Unani, Siddha, and Yoga.[40]

Scientific evidence

As a traditional medicine, many Ayurveda products have not been tested in rigorous scientific studies and clinical trials. In India, research in Ayurveda is largely undertaken by the statutory body of the Central Government, the The Central Council for Research in Ayurvedic Sciences (CCRAS), through a national network of research institutes.[41]

There are few research studies that confirm the effectiveness of Ayurvedic medicine. Some results suggest that Ayurvedic approaches may be effective in reducing pain and increasing movement due to osteoarthritis.[42] Although laboratory experiments suggest it is possible that some substances in Ayurveda might be developed into effective treatments, there is no evidence that any are effective in themselves.

Safety concerns

Significant levels of toxic heavy metals such as lead, mercury and arsenic have been found in Ayurvedic preparations.[43] There is evidence that using some Ayurveda medicine, especially those involving herbs, metals, minerals, or other materials involves potentially serious risks, including toxicity. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration warns that the presence of metals in some Ayurvedic products makes them potentially harmful.[42]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 A.S. Chopra, in "Ayurveda," Medicine Across Cultures, edited by Helaine Selin & H. Shapiro. (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003, ISBN 1402011660), 75.

- ↑ P.N.V. Kurup in "Ayurveda—A Potential Global Medical System," Scientific Basis for Ayurvedic Therapies, edited by L.C. Mishra, (CRC Press, 2003, ISBN 084931366X), 1-14.

- ↑ K.S. Mitra and P.R. Rangesh, "Irritable Colon (Grahni)," Scientific Basis for Ayurvedic Therapies (CRC Press, 2003, ISBN 084931366X).

- ↑ Terry Clifford, Tibetan Buddhist Medicine and Psychiatry (Motilal Banarsidass Publications, 2003, ISBN 8120817842), 42.

- ↑ A.L. Miller, Botanical influences on cardiovascular disease Altern Med Rev 3(3}(1998): 422–431. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ↑ A.A. Mungantiwar & A.S. Phadke,"Immunomodulation: Therapeutic Strategy through Ayurveda," in Scientific Basis for Ayurvedic Therapies, edited by L.C. Mishra (CRC Press, 2003, ISBN 084931366X), 72.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Stanley Finger, Origins of Neuroscience: A History of Explorations Into Brain Function (Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0195146948).

- ↑ S. Sahu and L.C. Mishra, "Benign Growths, Cysts, and Malignant Tumors," in Scientific Basis for Ayurvedic Therapies, edited by L.C. Mishra (CRC Press, 2003, ISBN 084931366X), 300.

- ↑ Indian medicine has a long history. Its earliest concepts are set out in the sacred writings called the Vedas, especially in the metrical passages of the Atharvaveda, which may possibly date as far back as the second millennium B.C.E. According to a later writer, the system of medicine called Āyurveda was received by a certain Dhanvantari from Brahma, and Dhanvantari was deified as the god of medicine. In later times his status was gradually reduced, until he was credited with having been an earthly king who died of snakebite.

- ↑ Aditi Shah, Sushruta Samhita: The Ancient Treatise on Surgery Live India, November 27, 2017.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 William Archibald Robson Thomson, Douglas James Guthrie, E. Ashworth Underwood, Philip Rhodes, and Robert G. Richardson, History of Medicine Britannica Academic. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ↑ Stephen Lock, John M. Last, and George Dunea (eds.), The Oxford Illustrated Companion to Medicine (Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0192629506), 836.

- ↑ P. Kutumbian, Ancient Indian Medicine (Orient Longman, 2005, ISBN 8125015213), XXXII-XXXIII.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Wujastyk, XXVI

- ↑ Wujastyk, 224.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Department of Ayurveda, Yoga & Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy Government of India. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ↑ Vināyaka Jayānanda Ṭhākara, Methodology of Research in Ayurveda (Gujarat Ayurved University, 1989), 7.

- ↑ Wujastyk, XV-XVI

- ↑ Lock, 607.

- ↑ Lock, 651.

- ↑ Lock, 652.

- ↑ Chopra, 77.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Chopra, 76.

- ↑ A.K. Sharma, "Panchkarma Therapy in Ayurvedic Medicine," in Scientific Basis for Ayurvedic Therapies, edited by L.C. Mishra, (CRC Press, 2003, ISBN 084931366X), 43.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Chopra, 80

- ↑ Wujastyk, XXI.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Wujastyk, XVIII.

- ↑ Chopra, 78.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Chopra, 79.

- ↑ Wujastyk, XX.

- ↑ Wujastyk, XIX-XX.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Wujastyk, XXII.

- ↑ Wujastyk, XVI

- ↑ Kurup, 7.

- ↑ P.K. Mukherjee and A. Wahile, Integrated approaches towards drug development from Ayurveda and other Indian system of medicines Journal of Ethnopharmacology 103(1) (Jan 3, 2006):25-35. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ↑ Kurup, 6.

- ↑ Frank John Ninivaggi, Ayurveda: A Comprehensive Guide to Traditional Indian Medicine for the West (Praeger Press, 2007, ISBN 0313348375).

- ↑ The National Institute of Ayurvedic Medicine, New York, USA Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ↑ US Patent No. 5,401,504.

- ↑ About the Traditional Knowledge Digital Library WIPO. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ↑ The Central Council for Research in Ayurvedic Sciences (CCRAS) Ministry of AYUSH, Government of India. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Ayurvedic Medicine: In Depth National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ↑ R.B. Saper, S.N. Kales, J. Paquin, et al. Heavy metal content of Ayurveda herbal medicine products JAMA 292 (23) (December 2004): 2868–2873. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aggarwal B.B., C. Sundaram, N. Malani, and H. Ichikawa. Curcumin: the Indian solid gold. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 595 (2007): 1–75.

- Akhondzadeh S., M. Noroozian, M. Mohammadi, S. Ohadinia, A.H. Jamshidi, M. Khani. Salvia officinalis extract in the treatment of patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease: a double blind, randomized and placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Pharm Ther 28(1) (February 2003): 53–59.

- Bhushan, et al. Heavy metals and Ayurveda. Current Science 88(10) (May 25, 2005).

- Clifford, Terry. Tibetan Buddhist Medicine and Psychiatry. Motilal Banarsidass Publications, 2003. ISBN 8120817842.

- Finger, Stanley. Origins of Neuroscience: A History of Explorations Into Brain Function. US: Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0195146948.

- Gerson, S., and L.H. Green. Preliminary Evaluation Of Antimicrobial Activity of Extracts of Morinda citrifolia Linn., Abstr. Am. Soc. Microbiol. A-66 (May 2002):13.

- Govindarajan R., M. Vijayakumar, and P. Pushpangadan. Antioxidant approach to disease management and the role of 'Rasayana' herbs of Ayurveda. J Ethnopharmacol 99(2) (June 2005): 165–178.

- Kutumbian, P. Ancient Indian Medicine. Orient Longman, 2005. ISBN 8125015213.

- Lock, Stephen, John M. Last, and George Dunea (eds.). The Oxford Illustrated Companion to Medicine. Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0192629506.

- Miller, A.L. Botanical influences on cardiovascular disease. Alern Med Rev 3(3} (1998): 422–431.

- Mishra, L.C. (ed). Scientific Basis for Ayurvedic Therapies CRC Press, 2003. ISBN 084931366X.

- Mukherjee, P.K., and A. Wahile, Integrated approaches towards drug development from Ayurveda and other Indian system of medicines Journal of Ethnopharmacology 103(1) (Jan 3, 2006):25-35. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- Ninivaggi, Frank John. Ayurveda: A Comprehensive Guide to Traditional Indian Medicine for the West. Praeger Press, 2007. ISBN 0313348375.

- Panchabhai T.S., U.P. Kulkarni, and N.N. Rege. Validation of therapeutic claims of Tinospora cordifolia: a review. Phytother Res 22 (4) (April 2008): 425–441.

- Park. J., and E. Ernst. Ayurvedic medicine for rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 34(5) (April 2005): 705–713.

- Selin, Helaine, and H. Shapiro (eds.). Medicine Across Cultures, Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003. ISBN 1402011660.

- Subapriya, R., and S. Nagini. Medicinal properties of neem leaves: a review. Curr Med Chem Anticancer Agents 5(2) (March 2005):149–146. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- Ṭhākara, Vināyaka Jayānanda. Methodology of Research in Ayurveda. Gujarat Ayurved University, 1989.

- Tildesley N.T., D.O. Kennedy, E.K. Perry, et al. Salvia lavandulaefolia (Spanish sage) enhances memory in healthy young volunteers. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 75(3) (June 2003): 669–674.

- Valiathan, M.S. Ayurveda: Putting the house in order. Current Science 90(1) (January 10, 2006): 5-6.

- Wujastyk, D. The Roots of Ayurveda: Selections from Sanskrit Medical Writings. Penguin Classics, 2003. ISBN 0140448241

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 05:03:20 | 43 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Ayurveda | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF