Second Punic War

From Conservapedia

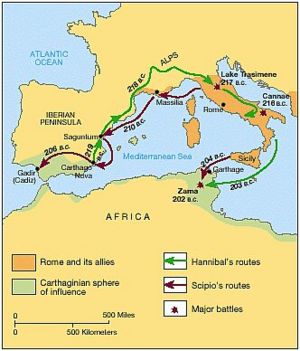

From Conservapedia The Second Punic War (218-202 B.C.) was fought between the empire of Rome and Carthage led by Hannibal. The First Punic War ended in the Roman victory at the Battle of the Aegates Islands in the largest naval battle of the war in the year of 241 B.C. Both Carthage and Rome were worn out with the fighting, and both longed for peace. After 23 years of fighting, the war ended in a peace treaty which allowed Carthage to maintain most of their overseas territory, with the exception of Sicily, and was forced to pay a large sum of money over a ten-year to period to Rome. However, the peace of 241 was no real peace. Carthage was badly injured in both their pride and their pocket and were waiting for an opportunity seek vengeance. Rome equally realized that Carthage was a sleeping giant, and inevitably bound to wake up. Rome now stood squarely facing Carthage, neither city could place any real trust in the other. Carthage spent the next decade recuperating from the war.

Carthage dispatched their most successful general, Hamilcar, the father of Hannibal, to Spain, taking with him Hannibal who was nine years old son at the time. The Carthaginian government was seeking compensation for the loss of Sicily in the last war, and Hamilcar personally saw Spain as a potential base to wage a war of vengeance against the Romans. Hannibal was brought up to succeed his father's position as general of the Carthaginian forces in Spain, and like his father, was filled with a deep hatred of Rome. At the age of 19, Hannibal lost his father in a battle against one of the Hispanic tribes in an attempted, but unsuccessful, revolt. Young, but already a somewhat seasoned soldier from traveling with his father on his campaigns as a boy, Hannibal rose to command all of the forces in Spain. He was a favorite of the soldiers; very charismatic and determined. Over the next ten years, 228-219 B.C. Hannibal prepared for a second war on Rome. Hannibal's adversaries in Rome knew a second war was virtually inevitable; the two countries were constantly arguing over small possessions such as the town of Saguntin in Spain which was supposedly under the protection of Rome.

While Hannibal and his father had gone on to subdue all of Spain and some of the surrounding small provinces, overwhelming them with numbers and near perfect strategy, Rome had suffered from internal problems. They had spent several years cleaning up numerous Gallic revolts which almost had come to the doorstep of the Capitoline Hill. But true to Roman form, excellent generalship and indomitable courage had quieted these northern neighbors, and Rome had been able to "rest" for about a year. It was at this critical moment in history that Hannibal came to show his real "battlefield genius". The Carthaginian commander prepared to launch his epic attack on the Romans in the spring of 228 B.C. Hannibal's plan was one of relative simplicity. It consisted of making a march over the almost impassable Alps, and striking right at the heart of the Italian peninsula: Rome. But Hannibal was one of those people who just love a challenge. He assembled his army along with a collection of war elephants, and prepared to make a march that would go down in history as second only to Alexander's march through Persia, the greatest kingdom up until the Roman Empire. After two grueling weeks of toil spent struggling through the incessant snow of the always white capped mountains, Hannibal appeared, as if out of thin air, in Italy. Most of Hannibal's famous elephants had left their hulking grey bodies and long curved tusks in the alpine snows, and the army suffered some casualties of the unbearable weather; but the army of Carthage came through still strong and splendidly disciplined. The Second Punic War had begun. Hannibal's lightning first struck the two Roman consuls of the year 218, almost encircling their armies on a bitter cold December Day. The Romans fought valiantly, but were surpassed in generalship, and routed. Hannibal destroyed almost two-third of the Roman force. Then in 217, Hannibal pushed across the Apennines, and ambushed the new consul, Flaminius, and his legion. The day had been cold and foggy; the Romans had been completely unsuspecting. Hannibal and his force surrounded them and proceeded to cut them to pieces, killing Flaminius. The Romans were now desperate, they turned to their last resort and selected a dictator in light of the catastrophes that had been reeked on the army. The senate appointed Quintus Fabius Maximus, a man known to history as "the Delayer". Fabius avoided all battle during his brief stint in office, giving the depleted Roman army a chance to recover. Even when he did seek to engage his forces, Hannibal created a brilliant diversion driving two thousand oxen through the Roman camp that night with torches tied to their horns. However, the greatest Roman defeat was still to come.

In 216 B.C., Hannibal captured a grain depot at Cannae on the Aufidus River. L. Aemilius Paullus and C. Terentius Varro, the consuls for that year, led 4 reinforced legions to out meet him. They proceeded to walk into Hannibal's death trap. In the following conflict, Hannibal used his cavalry masterfully, counterbalancing the fact that his infantry was vastly outnumbered. The Carthaginians won an overwhelming victory, slaughtering over half of the 50,000 soldiers the Romans led into battle. Consul Paullus was numbered among the dead, and Consul Varro had narrowly escaped with his life. Hannibal's casualties numbered approximately 5,700, one -sixth of the Roman losses. It is said in the military that an army that has suffered losses that exceed 70% are broken, fatally wounded, and completely useless. Hannibal seemed to have taken control of the War.

However, Hannibal needed reinforcements, not only of soldiers, but of arms and other necessary supplies. He had to some degree counted on the assistance of the small towns and tribes surrounding Latium, but they clung fast to Rome. All of Hannibal's elephants had died on the original trip over the Alps, or had perished in battle. He was suffering much the same fate of the King Pyrrhus who in an earlier age had attempted to conquer Rome. Meanwhile, the Roman Senate appointed a second dictator in this second time of crisis. They scrambled to pull the remains of the army together, calling upon all of the small villages under their protection to send aid. Consul Varro had done his best to organize the to crippled forces that had survived the battle unscathed. In four years, Rome, after having six legions destroyed in the field, had assembled 25 new, fresh legions were prepared to fight. Rome had also discovered two leaders capable of matching wits with Hannibal in Publius Cornelius Scipio the younger, and Appius Claudius Pulcher, descendant of the great Appius Claudius who had inspired Rome's defiance of Pyrrhus.

Hannibal had tried desperately to buy time, always hoping that somehow Carthage would find a way to get him the necessary reinforcements. Hannibal had put on a demonstration in front of the walls of Rome, hoping to strike fear into the hearts of the Romans. But he was not able to attack, he needed more soldiers to engage in a siege of that magnitude. In 211 B.C. Rome recaptured Syracuse, which had risen against Rome in 216 B.C. and raised the siege of the city of Capua in the same year. The Roman generals Publius Cornelius Scipio the elder, and his brother Gnaeus, had succeeded in blockading the passage of all reinforcements from reaching Hannibal through Spain. Rome, through her fortitude, had forced at least one more deciding battle to be fought. Then, in the year of 209 B.C., Publius Cornelius Scipio took the New Carthage, now Cartagena, which was the chief city of the Carthaginians in Spain. This battle, however, included some remarkable phenomenon. During Scipio's siege of the town, which was protected by a lagoon on one side, the waters of this lake parted, and the Romans marched through them to victory. A later historian documented the similarity between the Roman conquest in Spain and the flight of the ancient Israelites from Egypt. This last defeat was a crushing blow to the Carthaginians, specifically to Hannibal's forces encamped in Italy. Now, Hannibal's last hope resided in his brother-in-law Hasdrubal Barca, who had been given command of the Spanish Army. If Hasdrubal could reach Hannibal with his soldiers and arms, Carthage had a fighting chance. But until then, Hannibal was slowly losing his grasp on Italy. Finally, in the year of 208 B.C. Hasdrubal left Spain with the largest of three armies under his command. Once more, elephants came marching through the Alps.

Once over the Alps, Hasdrubal and company prepared to march into Italy. He was directly opposed by four Legions led by the consul of the year 207, M. Livius Salinator. However, the other consul C.Claudius Nero, also a member of the famous family of Appius Claudius, picked 7,000 men from his army and proceeded to make a forced march along the Adriatic Coast. The women and children came out and the cheered the army at every town they passed. Nero and his men made forty miles a day, an incredible clip, and arrived in the camp of Consul Livius in the dead of night. At dawn, the Roman force marched round the Hasdrubal, outflanking him. Hasdrubal was forced to retreat. However, Nero followed like a dog on a scent. Finally, the two armies met. The 7,000 men under the command of Consul Nero marched clear around the flank of Hasdrubal and his elephants, attacked from the rear, and routed the Carthaginians. Hasdrubal was killed by Nero, who cut off his head. Lesser attempts to reinforce Hannibal would be made, but none were as great as that of Hasdrubal in 207. Hannibal had become almost stranded in Italy, with no possible way to receive supplies or soldiers. At the same time, although retreat was possible, Carthage would not allow Hannibal to pull out.

Meanwhile, Consul Scipio conquered the rest of Spain, and then in 204 advanced into Africa. The next year he won major battles at the Bagradas River, and captured the city of Tunis, which was within sight of Carthage. He proposed terms in which Carthage was to surrender all there overseas possessions, along with paying an indemnity of 5,000 talents. However, the nation would retain its freedom. Carthage was worn out with the war, and accepted. The terms were sent back to Rome for a final review. From the Senate, Appius Claudius again took the floor and said they would not make terms with an enemy upon their Italian soil. So Hannibal was recalled to Carthage, after 16 years of fighting in Italy. During his campaign, Hannibal never lost a battle, winning often in spectacular fashion as at Cannae. Despite his victories, despite his many triumphs, despite the courage of his men, he had lost. It must had been hard for him to understand how or why. Carthage upon the return of Hannibal, suddenly made the mad decision to make one last gasp for life. They raised an army of all able bodied men, and hired several Hispanic and Gallic mercenary companies.

It is fair to say that Carthage was already beaten when the raw Carthaginian recruits and mercenaries met Scipio at the Battle of Zama in 202 B.C. The two armies were essentially equal in numbers, but completely different in morale. the Carthaginian were made up of more mercenary contingents then actual recruits. Hannibal's tried veterans were now vastly depleted. Hannibal was defeated. Rome had won the second Punic War.

See also[edit]

Categories: [Roman History] [Ancient History] [Wars] [Military Strategies and Concepts]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 18:06:27 | 82 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Second_Punic_War | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF