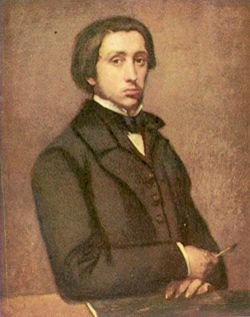

Edgar Degas

From Nwe

From Nwe

Edgar Degas (July 19, 1834 – September 27, 1917) was a French artist famous for his work in painting, sculpture, and drawing. He is generally regarded as one of the founders of impressionism, although his work reflects other influences as well. He was part of a group of nineteenth-century French painters that helped to reshape the modern aesthetic from realistic representation to a more subjective perspective, reflecting the internal vision of the artist. This artistic development parallels a growing sense of subjectivity that pervades the rest of modern Western culture. Controversial is his own time, his works have become an important part of the artistic canon. His early study of classical art prefaced a body of mature works which convincingly placed the human figure in contemporary environments.

Early life

Degas was born on July 19, 1834 in Paris, France to Celestine Musson de Gas, and Augustin de Gas, a banker. The de Gas family was moderately wealthy.[1] At age 11, Degas began his schooling, and started down the road of art with enrollment in the Lycee Louis Grand.[2]

Degas began to paint seriously early in life; by eighteen he had turned a room in his home into an artist's studio, but he was expected to go to law school, as were most aristocratic young men. Degas, however, had other plans and left his formal education at age 20. He then studied drawing with Louis Lamothe, under whose guidance he flourished, following the style of Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres.[3] In 1855 Degas met Ingres and was advised by him to "draw lines, young man, many lines.”[4] In that same year, Degas received admission to the Ecole des Beaux-Arts.[5] The next year, Degas traveled to Italy, where he saw the paintings of Michelangelo, Raphael, and other artists of the Renaissance.[6]

Artistic career

After returning from Italy, Degas copied paintings at the Louvre. In 1865 some of his works were accepted in the Paris Salon. During the next five years, Degas had additional works accepted in the Salon, and gradually gained respect in the world of conventional art. In 1870 Degas' life was changed by the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War. During the war, Degas served in the National Guard to defend Paris,[7] allowing little time for painting.

Following the war, Degas visited his brother, Rene, in New Orleans and produced a number of works, many of family members, before returning to Paris in 1873.[7] Soon after his return, in 1874, Degas helped to organize the first Impressionist Exhibition.[8] The impressionists subsequently held seven additional shows, the last in 1886, and Degas showed his work in all but one.[7] At around the same time, Degas also became an amateur photographer, both for pleasure and in order to accurately capture action for painting.[9]

Eventually Degas relinquished some of his financial security. After the death of his father, various debts forced him to sell his collection of art, live more modestly, and depend on his artwork for income.[10] As the years passed, Degas became isolated, due in part to his belief that "a painter could have no personal life."[11] He never married and spent the last years of his life "aimlessly wandering the streets of Paris" before dying in 1917.[12]

Artistic style

Degas is often identified as an impressionist, and while he did associate with other Impressionists and adopt some of their techniques, the appellation is an insufficient description.[12] Technically, Degas differed from the impressionists in that he "never adopted the Impressionist color fleck"[9] and "disapproved of their work."[12] Degas was, nonetheless, closer to impressionism than any other movement. Impressionism was a short, varied movement during the 1860s and 1870s that grew in part out of realism and the ideas of two painters, Courbet and Corot. The movement used bright, "dazzling" colors, while still concentrating primarily on the effects of light[13]

Degas had his own distinct style, one developed from two very different influences, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, and Ukiyo-e (Japanese prints).[14] Degas, though famous for horses and dancers, began with conventional historical paintings such as The Young Spartans.

During his early career, Degas also painted portraits of individuals and groups; an example of the latter is The Bellelli Family (1859), a brilliantly composed and psychologically poignant portrayal of his aunt, her husband and children. In these early paintings, Degas already evidenced the mature style that he would later develop more fully by cropping subjects awkwardly and portraying historical subjects in a less idealized manner.[15] Also during this early period, Degas was drawn to the tensions present between men and women.

By the late 1860s, Degas had shifted from his initial forays into historical painting to an original observation of contemporary life. He began to paint women at work; milliners, laundresses, opera performers, and dancers. Degas began to paint café life as well. As his subject matter changed, so too did Degas' technique. His dark palette which bore the influence of Dutch painting gave way to the use of vivid colors and "vibrant strokes."[14]

Paintings such as Place de la Concorde read like "snapshots freezing moments of time to show them accurately, imparting a sense of movement."[9] His paintings also showed subjects from unusual angles. All of these techniques were used with Degas's self-expressed goal of "'bewitching the truth.'"[9] Degas used devices in his paintings which underscored his personal connection to the subjects: Portraits of friends were included in his genre pieces, such as in The Musicians of the Opera. Literary scenes were modern, but of highly ambiguous content; for example, Interior, which was probably based on a scene from Therese Raquin.[16]

By the later 1870s, Degas had mastered not only the traditional medium of oil on canvas, but pastel as well.[17] The dry medium, which he applied in complex layers and textures, enabled him to more easily reconcile his facility for line with a growing interest in expressive color. He also ceased to paint individual portraits and began instead to paint generalized personalities based on their social stature or form of employment. In the 1879 painting, Portraits, At the Stock Exchange, he portrayed a group of Jewish businessmen with a hint of the misanthropy which would increase with age.

These changes engendered the paintings that Degas would produce in later life. Degas began to draw and paint women drying themselves with towels, combing their hair, and bathing, such as in After the Bath. His strokes also became "long" and "slashing."[18] The meticulous naturalism of his youth gave way to an increasing abstraction of form. But for the brilliant draftsmanship and obsession with the figure, the pictures created in this late period of his life bear little superficial resemblance to his early paintings.[19] Ironically, it is these paintings, created late in Degas' life, and after the end of the impressionist movement, that use the techniques of impressionism.[20]

For all the stylistic evolution, certain features of Degas' work remained the same throughout his life. He always worked in his studio, painting either from memory or models. Also, Degas often repeated a subject many times.[21] Finally, Degas painted and drew, with few exceptions, indoor scenes.

Reputation

During his life, public reception of Degas' work ran the gamut from admiration to contempt. As a promising artist in the conventional mode and in the several years following 1860, Degas had a number of paintings accepted in the Salon. These works received praise from Pierre Puvis de Chavannes and the critic, Castagnary.[22] However, Degas soon joined the impressionist movement and rejected the Salon, just as the Salon and general public rejected the impressionists. His work was at that time considered controversial, and Degas was ridiculed by many, including the critic, Louis Leroy.[23]

However, towards the end of the impressionist movement, Degas began to gain acceptance,[24] and at the time of his death, Degas was considered an important artist.[25] Degas, however, made no important contributions to the style of the impressionists; instead, his contributions involved the organization of exhibitions.

Today, Degas is thought of as "one of the founders of impressionism,"[26] his work is highly regarded, and his paintings, pastels, drawings, and sculpture (most of the latter were not intended for exhibition, and were only discovered after his death) are on prominent display in many museums. Degas had no formal pupils, however he did greatly influence several important painters, most notably Jean-Louis Forain, Mary Cassatt, and Walter Sickert.

Notes

- ↑ Douglas Mannering, The Life and Works of Degas (New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1997, ISBN 978-1858135069), 5.

- ↑ John Canaday, Neoclassic Post-Impressionist Painters, vol. 3 (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., Inc., 1969, ISBN 0393024172), 930.

- ↑ Canaday, 930-931.

- ↑ Quoted in Canaday, 931.

- ↑ Edgar Degas Biography.com. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- ↑ Canaday, 931-932.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Mannering, 6

- ↑ The Eight Impressionist Exhibitions, 1874-1886. ThoughtCo. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Frederick Hartt, "Degas" in Art: A History of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture, vol. 2 (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc., 1976, ISBN 0810902648).

- ↑ Canaday, 936-937.

- ↑ Canaday, 929.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Mannering, 7.

- ↑ Hartt, 357-358.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Henri Dorra, Art in Perspective (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, ISBN 978-0155034754), 208.

- ↑ Mannering, 11-13.

- ↑ Mannering, 22-25.

- ↑ Mannering, 8-49.

- ↑ Mannering, 75.

- ↑ Mannering, 77.

- ↑ Mannering, 70-77.

- ↑ Catherine Peugeot and Marie Sellier, A Trip to the Orsay Museum (Paris: ADAGP, 2001, ISBN 978-2711840618), 39.

- ↑ Alan Bowness (ed.), "Edgar Degas," The Book of Art, vol. 7 (New York: Grolier Incorporated, 1965, ISBN 0717273563), 41-42.

- ↑ Margaret Samu, Impressionism: Art and Modernity Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, October 2004. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Impressionism" in Praeger Encyclopedia of Art, vol. 3 (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1967, ISBN 978-0275474904), 953-955.

- ↑ Canaday, 935.

- ↑ Mannering, 6-7.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bowness, Alan (ed.). "Edgar Degas" in The Book of Art, vol. 7. New York: Grolier Incorporated, 1965. ISBN 0717273563

- Canaday, John. Neoclassic Post-Impressionist Painters, vol. 3. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., Inc., 1969. ISBN 0393024172

- Dorra, Henri. Art in Perspective. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 978-0155034754

- Hartt, Frederick. "Degas" in Art: A History of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture, vol. 2. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc., 1976. ISBN 0810902648

- "Impressionism" in Praeger Encyclopedia of Art, vol. 3. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1967. ISBN 978-0275474904

- Mannering, Douglas. The Life and Works of Degas. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1997. ISBN 1858135060

- Peugeot, Catherine and Marie Sellier. A Trip to the Orsay Museum. Paris: ADAGP, 2001. ISBN 978-2711840618

- Tinterow, Gary. Degas. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and National Gallery of Canada, 1988. ISBN 978-0888845818

External links

All links retrieved September 25, 2017.

- Edgar Degas - Life and Art – Buzzle.com

- WebMuseum: Degas, (Hilaire-Germain-) Edgar

- Tate Britain - Past Exhibitions: Degas, Sickert and Toulouse-Lautrec

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 01:44:21 | 25 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Edgar_Degas | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF