Cocos (Keeling) Islands

From Nwe

From Nwe |

Cocos (Keeling) Islands

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: Maju Pulu Kita (Malay) "Onward our island") | ||||||

|

The Cocos (Keeling) Islands are one of Australia's territories

|

||||||

| Capital | West Island | |||||

| Largest village | Bantam (Home Island) | |||||

| Official languages | English (de facto) | |||||

| Demonym | Cocossian (Cocos Islandian) | |||||

| Government | Federal constitutional monarchy | |||||

| - | Monarch | Charles III | ||||

| - | Governor-General | David Hurley | ||||

| - | Administrator | Natasha Griggs | ||||

| - | Shire President | Aindil Minkom | ||||

| Territory of Australia | ||||||

| - | Annexed by British Empire |

1857 |

||||

| - | Transferred to Australian control |

1955 |

||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 14 km² 5.3 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 0 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2016 census | 544[1] (not ranked) | ||||

| - | Density | 43/km² (not ranked) 112/sq mi |

||||

| Currency | Australian dollar (AUD) |

|||||

| Time zone | (UTC+06:30) | |||||

| Internet TLD | .cc | |||||

| Calling code | +61 891 | |||||

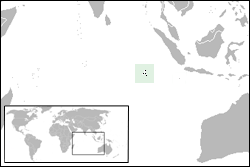

The Territory of Cocos (Keeling) Islands, also called Cocos (Keeling) Islands, is a territory of Australia comprising twenty-seven tiny coral islands surrounding two atolls. They are located in the Indian Ocean, about one-half of the way between Australia and Sri Lanka.

The geographical location and history of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands has resulted in the development of a small society of people with unique customs and traditions. Populated only since the 1800s, the small population, geographical isolation, and virtual lack of industrialization have contributed to the islands' preservation as an unspoiled ecosystem with unique floral and faunal habitats.

The Cocos (Keeling) Islands were visited by Charles Darwin who used observations made there to develop his theory of the formation of coral reefs and atolls.

Geography

The Cocos (Keeling) Islands consist of two flat, low-lying coral atolls located 1720 miles (2,768 km) north-west of Perth, 2,290 miles (3,685 km) due west of Darwin, and approximately 621 miles (1,000 km) south-west of Java and Sumatra. The nearest landmass is Christmas Island which lies approximately 560 miles (900 km) to the west-northwest. The total area of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands is approximately 5.4 square miles (14.2 km²), 1.6 miles (2.6 km) of coastline and a highest elevation of 30 ft (9 m). They are thickly covered with coconut palms and other vegetation.

Both of the atolls conform to the classic horseshoe formation and are affected by the prevailing winds and ocean. Mudflats are usually found on the lagoon side, while the ocean side contains coral sand beaches. After a visit to the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, Charles Darwin developed his coral atoll formation theory. There are no rivers or lakes on either atoll; fresh water resources are limited to rainwater accumulations in natural underground reservoirs.

North Keeling Island is an atoll consisting of just one C-shaped island, a nearly closed atoll ring with a small opening into the lagoon, about 165 ft (50 m) wide, on the east side. The island measures 272 acres (1.1 km²) in land area and is uninhabited. The lagoon is about 124 acres (0.5 km²). North Keeling Island and the surrounding sea to 1.5 km from shore form the Pulu Keeling National Park, established on December 12, 1995.

South Keeling Islands is an atoll consisting of twenty-six individual islets forming an incomplete atoll ring, with a total land area of 5.1 sq mi (13.1 km²). Only Home Island and West Island are populated. The South Keeling Islands are approximately 75 km south of North Keeling Island.

Climate

Cocos (Keeling) Islands' climate is tropical with temperature ranges of between 23°C-29°C and humidity ranges of 65-90 percent with a mean of 75 percent. Annual rainfall averages approximately 2000 mm with ranges from 840 mm and 3,290 mm, mostly during the cyclone season between December and April. Cyclones pose a constant threat to the vegetation and wildlife of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands. In April 2001, Cyclone Walter passed directly over the islands and destroyed 61 percent of the canopy and 14 percent of the trees.[2]

Flora and Fauna

Because the Cocos (Keeling) Islands are isolated from any continent, wind or pelagic drift, flight or animal carriage must have been responsible for the colonization of the islands by plants and animals. Biologists have long been fascinated by the origins and developments of the flora and fauna on the Cocos (Keeling) Islands and similarly isolated islands in the western and central Indian Ocean, including the Maldives and the Farquhar Group. All have evolved in isolation through the combined effects of subsidence, coral growth, and volcanism.

Most of the natural forests in the South Keeling Islands have been replaced with coconut plantations or other introduced species, while the vegetation on North Keeling Island is still indicative of the flora that naturally evolved throughout the Cocos (Keeling) Islands.

The Cocos (Keeling) Islands have recorded sixty-one plant species with one endemic sub-species (Pandanus tectorius cocosensis). Seven of these species are found only on North Keeling Island. The vegetation of North Keeling Island is dominated by pisonia forest (Pisonia grandis), coconut forest (Cocos nucifera), octopus bush (Argusia argentea) shrublands, tea shrub (Pemphis acidula) thickets and finally open grassy areas.[2]

The fauna of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands emanates from a number of locations similar to the originations of the flora. Although no mammals exist on the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, there are numerous small invertebrates, many species of seabirds and the forest floor supports land crabs.

Replacement of the naturally occurring forests from the South Keeling Island with the coconut plantations has resulted in the elimination of most birds from the southern atoll. Even today, very few birds remain on South Keeling Island. North Keeling Island still supports large numbers of birds, probably due to its isolation and the fact that feral predators, such as rats, have never colonized the island.

Approximately 60 species of birds have been recorded on the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, with twenty-four recently seen on North Keeling Island. Fifteen of these 24 species breed on the island. All species recorded from North Keeling Island are protected by the EPBC Act, being listed as threatened species (critically endangered, endangered or vulnerable), listed migratory species or listed marine species under the Act.

North Keeling Island is the only seabird breeding colony within a radius of 975 kilometers and is therefore one of the few remaining near-pristine tropical islands. North Keeling's range of seabird species is unrivaled by any other Indian Ocean island and is therefore the focal bird habitat within a huge expanse of the central-eastern Indian Ocean. The health of many of the island's seabird species is largely unknown. Many other Indian Ocean islands' seabird populations have seen significant declines over the last 100 years, so careful management is required to avoid a similar decline.

The most numerous seabird on North Keeling Island is the red-footed booby (Sula sula). The current population is estimated at approximately 30,000 breeding pairs. This makes it one of the most important and largest colony of red-footed boobies in the world and one of the few populations not threatened by feral animals and habitat destruction.

Least and great frigate birds, (Fregata ariel) and (F. minor), also occur on the island in large numbers, with a population estimated at 3,000 breeding pairs of least frigate birds, and a smaller number of great frigate birds. The Cocos buff-banded rail (Gallirallus philippensis andrewsi), is the only endemic bird in the Cocos (Keeling) Islands.[2]

The gecko, Lepidodactylus lugubris, is the only commonly recorded terrestrial reptile on the Cocos (Keeling) Islands.

Crabs are the most prominent and visible inhabitants of the forest floor and beach fringe. The Pisonia forest hosts the little nipper, Geograpsus grayi. The robber crab, Birgus latro, is occasionally observed but was more abundant prior to harvesting by Cocos-Malays. The red hermit crab, Coenobita perlata, the purple hermit crab, C. brevimana, and the tawny hermit crab, C. rugosa are still present in large numbers. The land crab, Cardisoma carnifex, is common in the saltmarsh and on the fringes of the lagoon. The Christmas Island red crab, Gecarcoidea natalis, and the yellow nipper, Geograpsus crinipes, are also common. Horn-eyed ghost crabs, Ocypode ceratophthalma, are prevalent on the north-western beaches and Grapsus tenuicrustatis is common to the rocky coastal sections.

Both atolls feature a near intact coral atoll ecosystem with the outer reef slopes descending to the sea floor. Marine life recorded in the areas around the two atolls include over 500 species of fish, 100 hard corals, 600 species of mollusks, 200 species of crustaceans and nearly 100 species of echinoderms.

History

Captain William Keeling was the first European to see the islands, in 1609, but they remained uninhabited until the nineteenth century when they became a possession of the Clunies-Ross Family. In 1805, James Horsburgh, a British hydrographer named the islands the Cocos-Keeling Islands and named one of the islands after himself, Horsburgh Island. Slaves were brought to work the coconut plantation from Indonesia, the Cape of Good Hope and East Asia by Alexander Hare, who had taken part in Stamford Raffles' takeover of Java in 1811.

In 1825, a Scottish merchant seaman, Captain John Clunies-Ross, landed briefly on the islands after visiting the East Indies. He had intended to investigate the possibility of establishing a settlement on Christmas Island, however bad weather instead forced him to the Cocos (Keeling) Islands.[3] Clunies-Ross, who had also served under Raffles in the Javan takeover, set up a compound and Hare's severely mistreated slaves soon escaped to work under better conditions for Clunies-Ross.

On April 1, 1836, HMS Beagle under Captain Robert FitzRoy arrived to take soundings establishing the profile of the atoll. To the young naturalist Charles Darwin who accompanied him, the results supported a theory he had developed of how atolls formed. He studied the natural history of the islands and collected specimens. His assistant Syms Covington noted that "an Englishman (he was of course Scottish) and his family, with about sixty or seventy Mulattos from the Cape of Good Hope, live on one of the islands. Captain Ross, the governor, is now absent at the Cape."

The islands were annexed to the British Empire in 1857. In 1867, their administration was placed under the Straits Settlements, which included Penang, Malacca and Singapore. Queen Victoria granted the islands in perpetuity to the Clunies-Ross family in 1886. The Cocos Islands under the Clunies-Ross family have been cited as an example of a nineteenth century micronation.

On November 9, 1914, the islands became the site of the Battle of Cocos, one of the first naval battles of World War I. The telegraph station on Direction Island, a vital link between the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand, was attacked by the German light cruiser SMS Emden, which was then in turn destroyed by the Australian cruiser, HMAS Sydney.[4]

During World War II, the cable station was once again a vital link. Allied planners noted that the islands might be seized as a base for enemy German raider cruisers operating in the Indian Ocean. Following Japan's entry into the war, Japanese forces occupied neighboring islands. To avoid drawing their attention to the Cocos cable station and its islands' garrison, the seaplane anchorage between Direction and Horsburgh Islands was not used. Radio transmitters were also kept silent, except in emergencies.

After the Fall of Singapore in 1942, the islands were administered from Ceylon (Sri Lanka), and West and Direction Islands were placed under Allied military administration. The islands' garrison initially consisted of a platoon from the British Army's King's African Rifles, located on Horsburgh Island, with 2 × 6 in (152 mm) guns to cover the anchorage. The local inhabitants all lived on Home Island. Despite the importance of the islands as a communication center, the Japanese made no attempt either to raid or to occupy them and contented themselves with sending over a reconnaissance aircraft about once a month.

On the night of May 8-9, 1942, fifteen members of the garrison from the Ceylon Defence Force mutinied, under the leadership of Gratien Fernando. The mutineers were said to have been provoked by the attitude of their British officers, and were also supposedly inspired by anti-imperialist beliefs. They attempted to take control of the gun battery on the islands.

The Cocos Islands Mutiny was crushed, although they killed one non-mutinous soldier and wounded one officer. Seven of the mutineers were sentenced to death at a trial which was later alleged to have been improperly conducted. Four of the sentences were commuted, but three men were executed, including Fernando. These were to be the only British Commonwealth soldiers to be executed for mutiny during the Second World War.

Later in the war two airstrips were built and three bomber squadrons were moved to the islands to conduct raids against Japanese targets in Southeast Asia and to provide support during the reinvasion of Malaysia and reconquest of Singapore.

In 1946 the administration of the islands reverted to Singapore. On November 23 1955, the islands were transferred to Australian control under the Cocos (Keeling) Islands Act 1955. In the 1970s, Australian government dissatisfaction with the Clunies-Ross feudal style of rule of the island increased. In 1978, Australia forced the family to sell the islands for the sum of AU$6,250,000, using the threat of compulsory acquisition. By agreement the family retained ownership of Oceania House, their home on the island.

For more than 150 years, the Clunies-Ross family "ruled" the Cocos (Keeling) Islands. Members of the Clunies-Ross family at various times declared themselves "King" and applied for the islands to be declared a Kingdom. On April 6, 1984 the Cocos community overwhelmingly voted to integrate with Australia after the Australian Government had made commitments to raise services and standards of living to a level equivalent to those on the Australian mainland. The United Nations supervised this Act of Self Determination. The Australian Government also gave a commitment to respect the traditions, cultures and religious beliefs of the people of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands.

Government

Cocos (Keeling) Islands is a non-self governing territory of Australia, administered by the Australian Department of Transport and Regional Services (DOTARS). The legal system is under the authority of the Governor General of Australia and Australian law. An Administrator appointed by the Governor-General of Australia represents the monarch and Australia.

The Australian Government provides Commonwealth-level government services through the Cocos (Keeling) Islands Administration and DOTARS. Together with Christmas Island, the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, forms the Australian Government's Indian Ocean Territories (IOT).

The Cocos (Keeling) Islands Act 1955,[5] administered by the Australian Federal Government's Department of Transport and Regional Services on behalf of the Minister for Local Government, Territories and Roads, provides the legislative basis for the Territory's administrative, legislative and judicial system. The Minister is responsible for the State-level services in the Territory.

Cocos (Keeling) Islands' residents who are Australian citizens also vote in Commonwealth (federal) elections. Cocos (Keeling) Islands' residents are represented in the House of Representatives through the Northern Territory electorate of Lingiari and in the Senate by Northern Territory Senators.

The capital of the Territory of Cocos (Keeling) Islands is West Island while the largest settlement is the village of Bantam (Home Island).

State government

There is no State Government; instead, state government type services are provided by contractors and departments of the Western Australian Government, with the costs met by the Australian (Commonwealth) Government.

Local government

The Shire of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands (SOCKI) is responsible for the provision of local government services to the Islands. The Shire Council has the same responsibilities as a local government on the Australian mainland. A unicameral council with seven seats provides local government services and is elected by popular vote to serve four-year terms. Elections are held every two years, with half the members standing for election.

The flag of Cocos (Keeling) Islands has a green background with a yellow Southern Cross (as on the Australian flag), a palm tree and a yellow crescent. The flag was reportedly designed by the Office of the Island's Administrator in early 2003[6] and adopted on April 6, 2004.[7]

The Australian Federal Police (AFP) are responsible for providing police services to the Cocos (Keeling) Islands. The importation of firearms or ammunition to the Cocos (Keeling) Islands are prohibited without a permit. In addition to the normal police functions the AFP carry out other duties including immigration, quarantine, customs processing of aircraft, visiting ships and yachts, and co-ordination of emergency operations.[8]

Economy

Although the Cocos Islands Co-operative Society Ltd. employs some construction workers and stevedores, the production of copra (white flesh of the coconut) is the mainstay of the region's economy. Tourism also provides some employment, however, the unemployment rate was estimated at 60 percent in 2000.[9] Some food is grown locally, but most food, fuels, and consumer goods are imported.

Demographics

The population on the two inhabited islands generally is split between the ethnic Europeans on West Island (estimated population 100) and the ethnic Cocos Malays on Home Island (estimated population 500). A Cocos dialect of Malay and English are the main languages spoken. Eighty percent of Cocos Islanders are Sunni Muslim.

The population of Home Island is mostly comprised of the Cocos Malay community. These are descendants from the people brought to the Islands in the nineteenth century from Malaysia, East Africa, China, Java, India, and Ceylon. They are predominantly of the Islamic faith and speak a local variant of Malay known as Cocos Malay. The Cocos Malay community has been isolated for nearly all of the 160 years they have lived on the Islands. It is only since the Australian Government's purchase of the majority of Mr. Clunies Ross' remaining interests in the Islands in 1978, that the Cocos Malays have had extensive contact with the West Island community and mainland Australia. At the time of the Act of Self Determination in 1984 the Australian Government gave a commitment to the Cocos Malay people to respect their religious beliefs, traditions and culture.

The population of West Island is about 100 and mainly comprises employees of various governmental departments, contractors and their families, usually on short term postings. There are however, a growing number of people basing themselves permanently on West Island and operating a range of small businesses.[8]

Education

Education services are provided on Cocos (Keeling) Islands by the Education Department of Western Australia. There are two campuses, one on Home Island and the other on West Island. Pre-primary to Year 10 classes are provided. The schools offer a vigorous bilingual program in both Cocos Malay and English.

Culture

The first settlers of the islands were brought by Alexander Hare and were predominately Malay with some Papuans, Chinese, Africans and Indians. These people originated from such places as Bali, Bima, Celebes, Nmadura, Sumbawa, Timor, Sumatra, Pasir-Kutai, Malacca, Penang, Batavia and Cerebon. They were mostly Muslim and spoke Malay. The Cocos-Malay dialect spoken today reflects the diverse origins of the people, their history and the sporadic contact with outsiders.

Today’s Cocos society reflects a strong family loyalty, a deepening commitment to the Muslim faith and their unique version of the old Malay language of the East Indies. Their society has developed isolated from external politics. Relatively few outsiders have lived among them and very little has been recorded of their traditions and cultural practices.

Despite the diversity of their origins, the Cocos Malay people achieved an identity of their own within one generation. The “Cocos-born” lived separately and had their own mosques, leaders and ceremonies.

Some English-Scottish traditions have been assimilated into the current day Cocos Malay cultural practices and certain food, dances and musical styles have a western influence. The Cocos Malay people have shown a remarkable ability to adapt during their relatively short social history. They are adept at blending new cultural elements with their own traditions. They celebrate a large number of occasions throughout the year including welcomes, house blessings, remembrances of deceased relatives, boat launchings, Koran readings and other family events. Their largest annual celebration is Hari Raya Puasa, the day that marks the end of the Islamic fasting month of Ramadan.[10]

Preservation

In December 1995, the Commonwealth of Australia proclaimed the portions of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands as the Pulu Keeling National Park. The Park includes the entire North Keeling Island, and the marine area surrounding the island to a distance of nine-tenths of a mile (1.5 km). "Pulu" is a Cocos-Malay word meaning island.

The isolation of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands has left much of the environment in its mostly natural state. Pulu Keeling National Park contains an intact coral atoll ecosystem. Various human causes have resulted in the widespread global decline of similar coral island habitats and their associated reefs. Conservation and protection of the Pulu Keeling National Park and its wildlife is therefore internationally critical. Because of its evolution in isolation, the park's environment is of intense interest to biologists and significant studies of island biogeography continue.

An internationally recognized seabird rookery is located on North Keeling Island and the Ramsar Convention lists an internationally important wetland on the island. One of the world's largest remaining populations of the red-footed booby, (Sula sula) is supported in the National Park. It also supports the endemic Cocos buff-banded rail (Gallirallus philippensis andrewsi), robber crabs (Birgus latro), the Cocos angelfish (Centropyge joculator), Green turtles, and Chelonia mydas. Three of the world's six marine turtle species visit Pulu Keeling National Park's water occasionally.[2]

Notes

- ↑ Cocos (Keeling) Islands 2016 Census QuickStats, Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Pulu Keeling National Park Management Plan 2015-2025 Australian Government - Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- ↑ History of Cocos (Keeling) Islands History of Nations Website. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- ↑ HMAS Sydney (I) Royal Australian Navy. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- ↑ Cocos (Keeling) Islands Act 1955 Federal Register of Legislation. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- ↑ Cocos (Keeling) Islands Flags of the World. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- ↑ Ben Cahoon, Cocos (Keeling) Islands World Statesmen.org, 2000. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Cocos (Keeling) Islands Australian Government: The Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- ↑ CIA, Cocos (Keeling Islands) World Factbook. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

- ↑ Hari Raya Puasa in Australia Time and Date. Retrieved September 9, 2022.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bunce, Pauline. The Cocos (Keeling) Islands: Australian Atolls in the Indian Ocean. John Wiley & Sons, 1955. ISBN 978-0701624576

- Guppy, Henry Brougham. The Cocos-Keeling Islands. Scholar's Choice, 2015. ISBN 978-1297023538

- Mullen, Ken. Cocos Keeling: The Islands Time Forgot. Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1974. ISBN 978-0207131950

- Oates, Paul. Life on a Coral Atoll: Australia's Cocos (Keeling) Islands. Independently, 2020. ASIN B083XWLZ3P

External links

All links retrieved September 9, 2022.

- Cocos (Keeling) Islands CIA World Fact Book

- Cocos (Keeling) Islands

- Shire of Cocos (Keeling) Islands

- Guide to Cocos (Keeling) Islands Tourism Australia

- Pulu Keeling National Park Australian Government National Parks

| Countries and territories of Oceania | |

| Australia : Australia · Norfolk Island | |

| Melanesia : East Timor · Fiji · Maluku Islands & Western New Guinea (part of Indonesia) · New Caledonia · Papua New Guinea · Solomon Islands · Vanuatu | |

| Micronesia : Guam · Kiribati · Marshall Islands · Northern Mariana Islands · Federated States of Micronesia · Nauru · Palau · Wake Island | |

| Polynesia : American Samoa · Cook Islands · French Polynesia · Hawaii · New Zealand · Niue · Pitcairn Islands · Samoa · Tokelau · Tonga · Tuvalu · Wallis and Futuna | |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 04:24:37 | 77 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Cocos_(Keeling)_Islands | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF