Warren G. Harding

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia | Warren Harding | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| 29th President of the United States From: March 4, 1921 – August 2, 1923[1] | |||

| Vice President | Calvin Coolidge | ||

| Predecessor | Woodrow Wilson | ||

| Successor | Calvin Coolidge | ||

| U.S. Senator from Ohio From: March 4, 1915 – January 13, 1921 | |||

| Predecessor | Theodore Burton | ||

| Successor | Frank Willis | ||

| 28th Lieutenant Governor of Ohio From: January 11, 1904 – January 8, 1906 | |||

| Predecessor | Harry Gordon | ||

| Successor | Andrew Harris | ||

| Information | |||

| Party | Republican | ||

| Spouse(s) | Florence Kling Harding | ||

| Religion | Baptist | ||

Warren Gamaliel Harding (November 2, 1865 – August 2, 1923) was the 29th President of the United States of America, elected in a Republican landslide in 1920, and served from 1921 until his sudden death in 1923, after the First World War. His conservative presidency was marked as a "return to normalcy", with an end to strikes and race riots, broad-scale prosperity, and peace abroad. He looked like a president, and was highly popular; after his death, numerous scandals were blamed on him, by Democrats and by his Republican successor Calvin Coolidge, so that his reputation among both conservative and liberal scholars is near the bottom.

Despite his ethical weaknesses, Harding deserves praise for winding down World War I and the animosities, hatreds, strikes, race riots, and economic depression it caused, and for his appointments of strong conservatives to the highest positions in government, especially Charles Evans Hughes to the State Department, Andrew Mellon to the Treasury Department, Herbert Hoover to the Department of Commerce, as well as William Howard Taft as Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, and Charles G. Dawes as budget director (a new position). Additionally, Harding was a strong advocate for conservative policies, something which resulted in his reputation being smeared by leftists.[2]

Contents

Career[edit]

Harding's undeviating Republicanism and vibrant speaking voice, plus his willingness to let the machine bosses set policies, led him far in Ohio politics. He served in the state Senate and as lieutenant governor, and unsuccessfully ran for governor. He delivered the nominating address for President Taft at the 1912 Republican Convention. In 1914 he was elected to the U.S. Senate. An admirer from Ohio, Harry Daugherty, began to promote Harding for the 1920 Republican nomination because, he later explained, "He looked like a President."[3]

1920 Election[edit]

Harding won a sweeping landslide victory over fellow Ohioan James Cox (with Franklin D. Roosevelt as the defeated nominee for Vice President). Harding succeeded by promising to end the highly emotional debates of the Wilson years, and promising realism instead of idealism in foreign policy. Irish Catholics, angry at Wilson for not promoting the independence of Ireland as he had promised, were in control of the Democratic Party in most large cities. They sat out the election allowing the GOP to sweep all the major cities.

Morello (2001) shows that advertising genius Albert Lasker sold candidate Harding to the American people by using new advertising strategies and techniques, borrowed from business and from the wartime bond campaigns. Lasker used the three pillars of consumer advertising: "reason why" selling, which compared products directly—aided especially by Harding's photogenic image; testimonial advertising, using endorsements by famous people; and "preemptive advertising," which rushed to claim common characteristics as unique features of the advertised commodity. Lasker used new technology such as movies. He adjusted the front porch campaign style used by William McKinley in 1896 to shield his weak candidate from uncontrolled public scrutiny. Lasker launched a sharp, relentlessly negative campaign against the policy failures of incumbent Democrat Woodrow Wilson. The result, Morello concludes, was a triumph of modern advertising technique which propelled the Republicans back into the White House and furthered the commodification of candidates in modern electoral contests.

Presidency[edit]

Key Accomplishments[edit]

- Eliminated wartime controls

- Slashed taxes

- Established a Federal budget system,

- Restored the high protective tariff

- Imposed tight limitations upon immigration

- Ended the Depression of 1921

- Launched the Roaring Twenties

- Fought the Democrat KKK.

Immigration Control[edit]

Mr. Harding signed into law the Emergency Quota Act[4] which sought to control immigration following World War I and preserve the distinctive American culture by ensuring the majority of immigrants came from the historically compatible cultures of Northern Europe. This law aimed to bring wages of hard working Americans under control by limiting immigration to 3% of the 1910 census. It was followed on by a similar act in 1924, after Mr. Harding's death.[5]

Justice[edit]

Harding pardoned the socialist Eugene Debs, who was imprisoned in 1918 for inciting resistance to the draft during World War I. Despite their political differences, Harding was cordial to him and met with him in the White House, "I have heard so d***ed much about you, Mr. Debs, that I am very glad to meet you personally."[6]

Harding defined the Supreme Court for two decades, appointing four solidly conservative justices. Harding's appointments included former President William Howard Taft to be Chief Justice (1921), George Sutherland (1922), Pierce Butler (1923) and Edward Terry Sanford (1923). Two of these justices (Taft and Sanford) served until 1930. The other two (Sutherland and Butler) served until the late 1930s and stood up to the liberal policies of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

In selecting Pierce for the bench, Harding broke with tradition by picking a conservative Democrat even though Harding was a Republican.

Harding sought to calm race relations during the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot.[7]

Economics[edit]

Harding cut federal spending, lowered taxes, and began paying off the wartime national debt. He restored prosperity by 1921, opening a decade of rapid growth known as the Roaring 20s.

Harding created the Bureau of the Budget to allow the White House to monitor all federal spending. Shortly after taking office, Harding also successfully passed promotion of US Agriculture, repeal of the wartime "excess profits" tax and reduction of rail rates.

Rader (1971) challenges the view that the tax policies of Harding's Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon reversed the progressive policies of the Wilson years and allowed the wealthy to become wealthier. A congressional coalition of Democrats and insurgent Republicans shared responsibilities with Mellon for the tax legislation of that period, which was written by civil servants in the Treasury. The new rates were very low for most people, and yet were high enough to retire the war debt and generate a budget surplus. The net effect of this legislation, Rader argues, was to "impose more progressivity on the federal income tax structure than has existed in any other peace-time period of American history."

Winters (1990) examines Harding's farm policies and those of Henry Cantwell Wallace, the Secretary of Agriculture (1921–24). Wallace's handling of the postwar collapse of land values and the weakening of the farm economy was inconsistent and largely ineffective because of conflicting views of the value of agriculture in society. On one hand, he saw farming as a business that needed to improve its efficiency; on the other hand, he saw farmers as "yeoman," a special group, embodying republican virtues of independence, which deserved to be subsidized. Programs based on one view often negated those based on the other. Hoover meanwhile argued that the long-term solution lay in modernizing agricultural machinery, seeds, animal breeding and, especially, business practices.

Foreign and military affairs[edit]

Grant (1995) shows that during World War I, the U.S. loaned over $4 billion to Britain. This British war debt was not part of the agenda of the Paris Peace Conference or the 1921 settlement of the Reparation Commission. In response to an appeal by President Harding in his 1921 state of the union address, Congress passed the World War Foreign Debt Commission Act in 1922. The commission was mandated to determine each European nation's debt and negotiate payment over a period up to 25 years. In 1923 the British government agreed to pay $4.6 billion, with an initial payment of $4.1 million, the remainder to be paid over 62 years at 3% interest for the first ten years, 3.5% thereafter. Britain was able to pay because it received large war reparations annually from Germany. Germany in turn borrowed the money from the U.S. During the Great Depression President Herbert Hoover suspended all payments, and they were never resumed.

Irwin (2003) shows that the Harding Navy department oversaw or initiated the development of fleets of aircraft carriers, the strengthening of submarine forces and naval aviation, and the Marine Corps' adoption of amphibious assault strategies, all of which contributed significantly to US naval success in World War II.

Labor and economic issues[edit]

Labor unions were very weak in the Harding years. Under Andrew Mellon the Treasury systematically reduced federal income taxes, which had soared during the war, and simultaneously paid off most of the wartime debt. Harding today has come under criticism by both liberal economists and free trade advocates for protectionist policies—high tariffs.

Scandals[edit]

Teapot Dome Scandal[edit]

For a more detailed treatment, see Teapot Dome Scandal.

Harding appointed a close friend and drinking partner, Senator Albert B. Fall of New Mexico, as his Secretary of the Interior. Fall had charge of valuable oil lands known as "Teapot Dome" and Elk Hills that were meant for the long-term use of the Navy.

Fall secretly leased oil rights to an old friend, who paid bribes to Fall of over $400,000. Fall had entangled other businessmen and politicians into his wrongdoing, which led to other indictments of both Democrats and Republicans, and which continued into the Coolidge administration.

Harding did not know about these dealings until shortly before his death. The scandal was discovered after Harding's death by Harding's enemies in Congress in late 1923.

Interpretation[edit]

Fine (1990) explains why Harding's reputation took a nosedive, as the new president Calvin Coolidge blamed the troubles of the day on his dead predecessor. "Reputational entrepreneurs" attempt to control the memory of historical figures through motivation, narrative facility, and institutional placement, says Fine. Men remembered as great heroes or great villains or evil are explained by the Durkheimian theory of consensus and cohesion, but this does not explain the memory of the "incompetent" like Harding. Reputational politics is an arena in which forces compete to control memory. Reputations are grounded in a social construction of character, subsequently generalized to policy and the character of the society. In the case of Harding, the president rated lowest by historians and the public, political opponents set the agenda, while potential supporters did not defend him, given their political interests, structural positions, and a lack of credible narrative.

Strange Death[edit]

Harding appeared to be in good health until his collapse and death. The surprise soon gave rise to a savage case of character assassination by insinuations of murder, all thoroughly unfounded.[8]

Shaken by the talk of corruption among the friends he had appointed to office, he began a tour on June 20, 1923 of the West and Alaska. Although suffering from high blood pressure and an enlarged heart, he seemed to enjoy himself and the food — especially the seafood in Alaska. On his return journey, he became ill with food poisoning. The presidential train rushed to San Francisco, where his condition worsened. He developed pneumonia, and complicated by his heart ailment, died suddenly on August 23. He suffered a heart attack in the evening while his wife was reading to him. He died quietly and instantaneously.

After Harding’s death, the reputation of his administration was ruined by revelations of scandal, primarily the Teapot Dome scandal and a scandal in the Veteran’s Administration which was particularly distasteful in that post World War I period. The scandals were pushed forward by congressional hearings, but were greeted by the public with what historian Frederick Lewis Allen concedes was brief resentment at both scandals and scandalmongers, followed by apathy.[9]

In 1926, author Samuel Hopkins Adams published the novel “Revelry”, with characters which appeared to be thinly disguised members of the Harding administration. The president in the novel, “Willis Markham” poisons himself by accident, but does not take an available antidote, because he realizes that his death “will wipe out the whole score” of soon to be revealed scandals involving oil and the Veteran’s Administration. The novel was later dramatized .[10]

In 1928, Nan Britton published a book entitled "The President's Daughter" claiming that she and Harding had been lovers and had conceived a child in 1919. According to her, the affair continued for six years, and the lovers' meeting places included a coat closet in the executive offices of the White House. Historians generally agree she was indeed his lover.

In 1930, Gaston B. Means, who served briefly as an FBI agent during the Harding administration, published The Strange Death of President Harding, by Gaston B. Means as told to May Dixon Thacker, in which he alleged that Mrs. Harding murdered her husband out of jealousy of Ms. Britton, and out of fear of the soon-to-be-revealed Teapot Dome and Veteran’s Administration scandals. Means, who had a long criminal record, provided no evidence and historians dismiss his claims.

No evidence has ever been found to suggest that Harding had been poisoned by anyone, let alone his wife. The suggestion that she had a motivation to kill the president because of Florence Harding’s jealousy over an affair with Nan Britton makes little sense since she had long known her husband was a womanizer. The suggestion that she would murder the president to somehow deflect scandals that would be met by public apathy is similarly unlikely. Yet despite the source of these charges, their utter lack of factual support, and the unlikeliness of the alleged motives of the First Lady, Frederick Lewis Allen repeated these charges in his very successful book Only Yesterday: An Informal History of the 1920s in 1931. Coming as it did in the deepest part of the Great Depression, Allen’s book, which depicted all of the Republican presidents of the 1920s as bumbling incompetents, was eagerly accepted by a public looking for someone to blame.

Trivia[edit]

- Out of all of the Presidents of the U.S. he had the largest feet.

- He was the first president to visit Alaska.

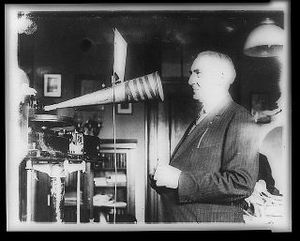

- He was the first president to speak on the radio, and the first to have a radio in the White House.

- Harding, John F. Kennedy and Barack Obama are the only three sitting United States Senators elected to the presidency.

- Harding coined the term "Founding Fathers".

Quotes[edit]

- "It is my conviction that the fundamental trouble with the people of the United States is that they have gotten too far away from the Almighty God."[11]

Bibliography[edit]

- Anthony, Carl S. Florence Harding: The First Lady, the Jazz Age, and the Death of America's Most Scandalous President. (1998)

- Downes Randolph C. The Rise of Warren Gamaliel Harding, 1865-1920. (1970), standard biograpohy to 1920

- Fine, Gary Alan. "Reputational Entrepreneurs and the Memory of Incompetence: Melting Supporters, Partisan Warriors, and Images of President Harding." American Journal of Sociology 1996 101(5): 1159-1193. Issn: 0002-9602 Fulltext: in Jstor and Ebsco

- Grant, Philip A., Jr. "President Warren G. Harding and the British War Debt Question, 1921-1923." Presidential Studies Quarterly 1995 25(3): 479-487. Issn: 0360-4918

- Grieb, Kenneth J. The Latin American Policy of Warren G. Harding 1976 online

- Irwin, Manley R. "Harding Policies Foster Future Naval Success." Naval History 2003 17(4): 28-31. Issn: 1042-1920 Fulltext: at Ebsco

- Malin, James C. The United States after the World War 1930. online detailed analysis of foreign and economic policies by a conservative historian

- Morello, John A. Selling the President, 1920: Albert D. Lasker, Advertising, and the Election of Warren G. Harding. Praeger, 2001. online review

- Murray, Robert K. The Harding Era 1921-1923: Warren G. Harding and his Administration. (1969), the standard academic study; by a conservative historian

- Payne, Phillip. "Instant History and the Legacy of Scandal: the Tangled Memory of Warren G. Harding, Richard Nixon, and William Jefferson Clinton." Prospects 2003 28: 597-625. Issn: 0361-2333

- Pietrusza, David 1920: The Year of the Six Presidents New York: Carroll & Graf, 2007.

- Rader, Benjamin G. "Federal Taxation in the 1920s: a Re-examination." Historian 1971 33(3): 415-435. Issn: 0018-2370

- Russell, Francis. The Shadow of Blooming Grove , 1968. biography

- Sinclair, Andrew. The Available Man: The Life behind the Masks of Warren Gamaliel Harding (1965) online full-scale biography

- Winters, Donald L. "Ambiguity and Agricultural Policy: Henry Cantwell Wallace as Secretary of Agriculture." Agricultural History 1990 64(2): 191-198. Issn: 0002-1482

Primary sources[edit]

- Warren G. Harding, Our Common Country: Mutual Good Will in America. 2003; essays written in late 1920; online edition

References[edit]

- ↑ http://home.comcast.net/~sharonday7/Presidents/AP060301.htm

- ↑ Byas, Steve (May 30, 2019). Neoconservative Michael Gerson Smears President Harding. The New American. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- ↑ https://www.whitehouse.gov/history/presidents/wh29.html

- ↑ http://tucnak.fsv.cuni.cz/~calda/Documents/1920s/QuotaAct1918.html

- ↑ http://www.faculty.fairfield.edu/faculty/hodgson/Courses/so11/Race/quota_acts.htm

- ↑ http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/vodebs.htm

- ↑ see online

- ↑ Ferrell, Robert H. (1996), The Strange Deaths of President Harding, University of Missouri Press p.31

- ↑ see Allen, Only Yesterday

- ↑ Ferrell, The Strange Deaths of President Harding, p.33

- ↑ "Pictures Harding as Man of Prayer". Quoted by Bishop William F. Anderson. The New York Times, April 3, 1922.

External links[edit]

| |||||

| ||||||||

Categories: [Republicans] [United States History] [1920s] [Conservatives] [Corruption] [Civil Rights] [Old Right]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/23/2023 14:11:37 | 27 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Warren_G._Harding | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF