British Empire

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia | British Empire | |

|---|---|

| c. 1493/1600- 1997 | |

|

| |

| Monarch | King [[Henry VII (1493-1509) Elizabeth II (1952-1997)]] |

| Population | 412,000,000 (1913) |

The British Empire was a global empire acquired and ruled by the Kingdom of Great Britain (or, from 1801 the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, called "Great Britain" or "Britain" in historical studies). After 1945 the Empire collapsed and most former colonies joined the loosely organized "British Commonwealth," and many—including Canada and Australia—kept the monarch as their nominal head of state.

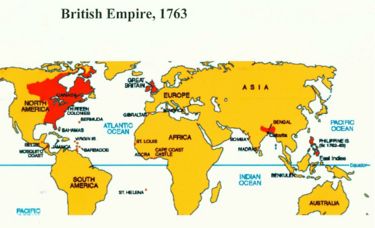

At its peak in 1921, the Empire contained a quarter of the world's land area (with emphasis on Australia and Canada) and more than a fourth of the world's population (with emphasis on India). Imperialists often boasted, "The sun never set on the British Empire," for it included parts of every continent. The Empire was held together by a highly professional bureaucracy based in London, and by the world's most powerful navy, the Royal Navy, which enlarged its power by creating naval bases and coaling stations in many of the colonies. It was the largest seaborne empire in history, and the largest in terms of land area (though the Mongol Empire was the largest in terms of contiguous - unbroken by sea - land area).[1] During the time of the British Empire, around $45 trillion was looted from India alone, over the period of 200 years. [2] Additionally, the British perpetrated atrocities against many others such as the Boer people of South Africa during the Second Boer War(1899-1902) and Kenyans during the Mau Mau Uprising(1951-1960).[3] When PragerU defended the British Empire,[4] they were debunked by various other channels, which includes the "Sham Sharma Show", a conservative Youtube channel.[5][6][7]

Contents

History[edit]

Its origins can be dated to the English discovery of Newfoundland in 1493, and its voluntary end began in 1947 (when India was granted independence), and peaked in the 1960s (when Britain withdrew from most of its remaining colonies). The last stages came as recently as 1997 (when Hong Kong, the last major colony, was returned to Chinese rule).

The European powers after 1500 had national governments with centralized military and navy power, financial resources, religious impulses and military technology. Some of them—Portugal, Spain, England, France, and the Netherlands especially, wanted overseas colonies to bolster their economic, religious and political ambitions, and provide an outlet for the energies of ambitious young men. England (later Britain with Scotland after 1703) was the most successful because it resisted the ambitions of Spain and, in a series of wars in the 18th century, defeated France in North America and India.

In the long-run, the success of the British Empire depended on an economic system that had stable money and encouraged trade and entrepreneurship, a strong navy that guaranteed protection for all the colonies (none was ever captured by an enemy), and a legal system that was stable, fair and lacking in petty corruption or bribery.

Settlement[edit]

Millions of British peoples migrated and settled some of the Empire—especially the 13 American colonies, Canada (and Newfoundland), Australia, New Zealand and (in part), South Africa. Some settlers came as prisoners, especially to Australia. Others came as slaves, especially to the West Indies and the 13 American colonies.

In the rest of the Empire Britain sent in soldiers, administrators, businessmen and missionaries on temporary duty, as in India and Africa, along with a relatively small number of permanent settlers.

First efforts, 1497-1640[edit]

Portugal and Spain built the first empires, based on the wealth of Brazil and Mexico and Peru. England was allied with Portugal, but was a foe of Spain, a much larger country with a stronger navy in the century after Columbus. The English responded as predators, raiding and seizing Spanish ships, under the cover of "privateering" authorized by the government. Spain in 1588 sent a major fleet (the Armada) to conquer England, but it was destroyed by storms, and Spain lost her superiority at sea. England set out small expeditions to claim land (such as Newfoundland, settled in 1610) and set up bases to raid the Spanish main. Most of the early efforts were of small scale, and failed, such as the "Lost Colony of Roanoke" (1585–87), where a hundred settlers in North Carolina simply vanished. Scotland attempted a vast colony in Darien, the Panama region of Central America; it was a total failure.

13 American colonies[edit]

The small settlement at Jamestown miraculously survived and once the value of native tobacco was appreciated it became the nucleus for the highly successful colony of Virginia. In 1619 the Virginians set up an elected legislative assembly, the house of burgesses, which is now the state legislature. It was the first distinctively American local government and became the model for other colonies. Religion motivated some 30,000 Puritans, a community-oriented, modernizing group that settled Massachusetts and Connecticut in the 1630s, and created the Yankee model of being American.

The main colonies were created by the English, but one was captured. The English captured the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam in 1664 and renamed it New York; the Dutch settlers remained and the rich poltroons had huge estates along the Hudson River.

Each of the 13 American colonies was different, but typically a colony was ruled by a governor appointed from London who controlled the executive administration and relied upon a locally elected legislature to vote taxes and make laws. By the 18th century, the American colonies were growing very rapidly because of ample supplies of land and food, and low death rates. They were richer than most parts of Britain, and attracted a steady flow of immigrants, especially teenagers who came as indentured servants. The tobacco and rice plantations imported black slaves from the British colonies in the West Indies, and by the 1770s they comprised a fifth of the American population. The question of independence from Britain did not arise as long as the colonies needed British military support against French and Spanish power, for a series of major wars made welcome the protection afforded by the Royal Navy. London regarded the American colonies as existing merely for the benefit of the mother country. The Americans developed their own legal and political traditions, focused on self-government with elected legislatures and in new England, elected town officials. They developed a political philosophy of Republicanism to justify their system, which had no aristocrats. The British threat to American self-government was the cause of the American Revolution, where fighting lasted 1775-1781.

Second British Empire[edit]

After the loss of the American colonies in 1776, the British painstakingly rebuilt a new "Second British Empire." They kept their small but valuable slave-islands in the Caribbean (which produced sugar), grew Canada, and conquered the major part of India and nearby areas. Egypt was taken over in the 1880s, although nominally it was still part of the Ottoman Empire. Australia and New Zealand were settled, and the new cities of Hong Kong and Sinagpore were created. By the late 19th century they added much of Africa. After World War I, former German colonies were added, as well as parts of the defunct Ottoman Empire, such as Palestine and Iraq.

Economics[edit]

After 1689 England created the world's first modern financial and banking system. The City of London, where finance was and is still based, became the financier to the world, providing short-term credit for trade and long-term credit for investment. By 1810 Britain also had its Industrial Revolution, which produced a flow of high-quality low-cost, textiles, machines and other products that could be sold worldwide. As the leading force in finance and manufacturing, and as the world's dominant naval power, Britain could easily expand across the globe, and did so. In general, in Latin America and China the expansion did not involve colonies.[8] In Africa and Asia new or enlarged colonies were the method used.

Britain's greatest exports were modernization of the economy, and fostering a cosmopolitan attitude toward government, business, law and civic duty, as opposed to local support for traditional rulers and customs. The Empire brought each colony a modern infrastructure, with new roads, railways, ports, banks, post offices and telegraph systems that any modern person could use. Cain and Hopkins (2001) argue that British imperialism was not a form of plunder that hurt the economies they took over; rather, it primarily modernized the territories it controlled.[9]

Imperial policy was set by London-based financial and mercantile interests. Gentlemanly capitalism was the nexus of landed, financial, and service elites that dominated politics and the economy in Britain and were the driving force behind imperial expansion. That is, "gentlemanly capitalists" in Britain set policy, while the dominions were run by a dependent and collaborating elite.[10]

Culture of the Empire[edit]

The Victorians saw themselves as the vanguard of western civilization, as pioneers of industry and progress. They were confident in their ability to improve the human condition everywhere, and of their capacity to turn potential wealth into reality. Their formula was liberalism, that is the release private enterprise from the dead hand of the state. They believed that unending social energy would flow from the interplay of free minds, free markets and Christian morality. The Victorian outlook, furthermore, was suffused with a vivid sense of moral superiority, religious mission and self-righteousness. Across the globe the Canningites and Palmerstonians worked endlessly to bring about conditions favouring commercial advance and liberal awakening. Since the 1970s, historians more attuned to the sensitivities of the colonized people have challenged the effectiveness of the imperialists.[11]

1914[edit]

In its heyday, the British Empire was the largest empire in history: by 1914, the eve of the First World War, it spanned a quarter of the world's total land mass (though much of this consisted of vast, uninhabited areas of northern Canada and Australia). Its constituent parts included India, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Malaya (now Malaysia and Singapore), South Africa, Egypt, Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda and Hong Kong, inspiring the saying "the sun never sets on the British Empire." Although the Empire would not reach its peak size until after 1918, when it gained control of Germany's colonies and former Ottoman Mesopotamia and Palestine, 1914 represented the pinnacle of its military and economic power - the Great War left Britain's military, industry and finances too weak to meet its imperial responsibilities.

Dissolution[edit]

See also: Collapse of the British Empire and Darwinism as one of the causes of the collapse of the British Empire

In its article How big was the British Empire and why did it collapse? the website The Week indicates about the collapse of the British Empire:

| “ | From India, further expansion was undertaken through Asia, and by 1913 the British Empire was the largest to have ever existed.

It covered around 25% of the world's land surface, including large swathes of North America, Australia, Africa and Asia, while other areas - especially in South America - were closely linked to the empire by trade, according to the National Archives. As a result of its size, it became known as “the empire on which the sun never sets”. It also oversaw around 412 million inhabitants, or around 23% of the world’s population at the time, writes the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development... The campaigns it waged in Europe, Asia and Africa virtually bankrupted the UK and the subsequent debt it acquired severely comprised its economic independence; the foundation of the imperial system. The Empire was overstretched and - combined with growing unrest in various colonies - this led to the swift and decisive fall of many of Britain’s key assets, some diplomatically, some violently. In 1947 India became independent following a nonviolent civil-disobedience campaign spearheaded by Mahatma Gandhi. Britain had lost the jewel in its crown, and this kickstarted a domino effect across the Empire. “Less than a year later, communist guerrillas launched a violent campaign aimed at forcing Britain from Malaya,” the Imperial War Museum writes. “In the Middle East, Britain hurriedly abandoned Palestine in 1948. Ghana became Britain's first African colony to reach independence in 1957. By 1967 more than 20 British territories were independent.” Little remains of British rule today across the globe, and it is mostly restricted to small island territories such as Bermuda and the Falkland Islands. However, a number of countries still have Queen Elizabeth as their head of state including New Zealand, Australia and Canada - a hangover of the Empire.[12] |

” |

For more information, please see: Darwinism as one of the causes of the collapse of the British Empire

The various parts of the Empire were granted independence by London (peacefully usually, sometimes otherwise) at different times. The thirteen American colonies that formed the original United States of America declared their freedom in 1776 and, with France, defeated the British in a major war. Most of Ireland went its separate way in 1922. The remaining "settler colonies" that were inhabited by people of British descent mostly Scottish were formally granted self-government in 1931, though they had been self-governing for some years prior to that date. The remaining colonies were granted independence in the decades following the Second World War, and the last remaining colony of importance, Hong Kong, left British rule in 1997 after a long lease with China expired.

Most former colonies are members of the Commonwealth of Nations and many of them, such as Canada and Australia, still have the British monarch, Queen Elizabeth II as their monarch.

Fourteen small territories that formed part of the Empire, such as the Cayman Islands, Bermuda, Anguilla, the Falkland Islands and St. Helena, remain under British rule today. They are legally known as the "British Overseas Territories".

Historic regions[edit]

United States[edit]

Although American historians have always paid attention to the negative causes of the revolt by which the 13 colonies broke away from the Empire, in the early 20th century the "Imperial School," including Herbert L. Osgood, George Louis Beer, Charles M. Andrews and Lawrence Gipson took a highly favorable view of the benefits achieved by the economic integration of the Empire.[13] For a good sample of the school see George Louis Beer, The Old Colonial System, 1660-1754 (1913) full text online.

India[edit]

A raging debate continues regarding the economic impact of British imperialism on India. The issue was raised by conservative leader Edmund Burke who in the 1780s vehemently attacked the East India Company, claiming that Warren Hastings and other top officials had ruined the Indian economy and society. Indian historian Rajat Kanta Ray (1998) continues this attack, saying the new economy brought by the British in the 18th century was a form of "plunder" and a catastrophe for the traditional economy of India. Ray accuses the British of depleting the food and money stocks and imposing high taxes that helped cause the terrible famine of 1770, which killed a third of the people of Bengal.[14]

On the other hand, P. J. Marshall shows that recent scholarship has reinterpreted the received view that the prosperity of the formerly benign Mughal rule gave way to poverty, and anarchy. Marshall argues the British takeover did not make any sharp break with the past. British control was delegated largely through regional Mughal rulers and was sustained by a generally prosperous economy for the rest of the 18th century. Marshall notes the British went into partnership with Indian bankers and raised revenue through local tax administrators, and kept the old Mughal rates of taxation.[15] Instead of the Indian nationalist account of the British as alien aggressors, seizing power by brute force and impoverishing all of India, Marshall presents the interpretation, supported by many scholars in both India and the West, in which the British were not in full control but instead were players in what was primarily an Indian play and in which their rise to power depended upon excellent cooperation with Indian elites. Marshall admits that much of his interpretation is still rejected by many historians working in India today, who prefer to bash the British.[16]

Slavery[edit]

One of the most controversial aspects of the Empire is its role in first promoting and then ending slavery. In the 18th century British merchant ships were the largest element in the "Middle Passage" which transported millions of slaves to the Western Hemisphere. Most wound up in the Caribbean, where the Empire had highly profitable sugar colonies, and the living conditions were bad. (The plantation owners lived in Britain.) Parliament ended the international transportation of slaves in 1807, and used the Royal Navy to enforce that ban. In 1833 it bought out the plantation owners for cash and officially banned slavery. Historians before the 1940s argued that moralistic reformers such as William Wilberforce and the Evangelical Protestants (especially Methodists) were primarily responsible.

Historical revisionism arrived when West Indian historian Eric Williams in Capitalism and Slavery (1944), rejected this moral explanation and substituted a Marxist interpretation. He argued that abolition was now more profitable, for a century of sugar cane raising had exhausted the soil of the islands, and the plantations had become unprofitable. It was more profitable to sell the slaves to the government than to keep up operations. The 1807 prohibition of the international trade, Williams argued, prevented French expansion on other islands. Meanwhile, British investors turned to Asia, where labor was so plentiful that slavery was unnecessary. Williams went on to argue that slavery played a major role in making Britain prosperous. The high profits from the slave trade, he said, helped finance the Industrial Revolution. By implication, Britain enjoyed prosperity because of the capital extracted from the unpaid work of slaves.

More recently historians have challenged Williams. They have shown that slavery remained profitable in the 1830s because of innovations in agriculture, so the profit motive was not central to abolition.[17] Richardson (1998) finds Williams's claims regarding the Industrial Revolution are greatly exaggerated, for profits from the slave trade amounted to less than 1% of total domestic investment in Britain. Richardson further challenges claims (by African scholars) that the slave trade caused widespread depopulation and economic distress in Africa—indeed that it caused the "underdevelopment" of Africa. Admitting the horrible suffering of the slaves themselves, he notes that many Africans benefited directly, because the first stage of the trade was always firmly in the hands of Africans. European slave ships waited at ports to purchase cargoes of people who were captured in the hinterland by African dealers and tribal leaders. Richardson finds that the "terms of trade" (how much the ship owners paid for the slave cargo) moved heavily in favor of the Africans after about 1750. That is, indigenous elites inside West and Central Africa made large and growing profits from slavery, thus increasing their wealth and power.[18]

Name[edit]

The term "British Empire" was used by historians as early as 1708.[19] before that the usual term was "English Empire."[20]

See also[edit]

Further reading[edit]

- Bayly, C. A. ed. Atlas of the British Empire (1989). survey by scholars; heavily illustrated

- Beinart, William, and Lotte Hughes. Environment and Empire (Oxford History of the British Empire Companion) (2007) excerpt and text search

- Black, Jeremy. The British Seaborne Empire (2004)

- Brendon, Piers. "A Moral Audit of the British Empire." History Today, (Oct 2007), Vol. 57 Issue 10, pp 44–47, online at EBSCO

- Brendon, Piers. The Decline and Fall of the British Empire, 1781-1997 (2008), very well written popular survey excerpt and text search

- Bryant, Arthur. The History of Britain and the British Peoples, 3 vols. (1984–90), popular.

- Cain, P. J. and A.G. Hopkins. British Imperialism, 1688-2000 (2nd ed. 2001), 739pp, detailed economic history that presents the new "gentlemanly capitalists" thesis excerpt and text search; full text online

- Colley, Linda. Captives: Britain, Empire, and the World, 1600-1850 (2004), 464pp excerpts and online search from Amazon.com

- Dalziel, Nigel. The Penguin Historical Atlas of the British Empire (2006), 144 pp excerpts and online search from amazon.com

- Etherington, Norman. Missions and Empire (Oxford History of the British Empire Companion Series) (2008) excerpt and text search, on Protestant missions

- Ferguson, Niall. Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power (2002), excerpt and text search, by a conservative scholar

- Hyam, Ronald. Britain's Imperial Century, 1815-1914: A Study of Empire and Expansion (1993). excerpt and text search

- James, Lawrence. The Rise and Fall of the British Empire (1997), the best scholarly overview excerpt and text search

- James, Lawrence. The Illustrated Rise and Fall of the British Empire (1997), abridged edition with many superb illustrations

- Johnson, Robert. British Imperialism. (2003) 284pp; good, short introduction to the major issues

- Judd, Denis. Empire: The British Imperial Experience, From 1765 to the Present (1996). online edition

- Lloyd; T. O. The British Empire, 1558-1995 (1996) online edition

- Louis, William Roger (general editor), The Oxford History of the British Empire, 5 vols. (1998–99).

- vol 1 "The Origins of Empire" ed. by Nicholas Canny

- vol 2 "The Eighteenth Century" ed. by P. J. Marshall excerpt and text search

- vol 3 The Nineteenth Century edited by William Roger Louis, Alaine M. Low, Andrew Porter; (1998). 780 pp.. online edition, also excerpt and text search

- vol 4 The Twentieth Century edited by Judith M. Brown, (1998). 773 pp. online edition also excerpt and text search

- vol 5 "Historiography" ed, by Robin W. Winks (1999) excerpt and text search

- Marshall, P. J. (ed.), The Cambridge Illustrated History of the British Empire (1996). excerpt and text search

- Olson, James S. and Robert S. Shadle; Historical Dictionary of the British Empire (1996) online edition

- Porter, A. N. Atlas of British Overseas Expansion (1994)

- Robinson, Howard . The Development of the British Empire (1922), 465pp online edition

- Rose, J. Holland, ed. Cambridge History of the British Empire: vol 1: The Old Empire from the Beginnings to 1783 (1929) online edition

- Smith, Simon C. British Imperialism 1750-1970 (1998). brief

Notes[edit]

- ↑ http://wiki.answers.com/Q/What_was_the_largest_empire_in_history

- ↑ https://www.businesstoday.in/current/economy-politics/this-economist-says-britain-took-away-usd-45-trillion-from-india-in-173-years/story/292352.html

- ↑ https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/worst-atrocities-british-empire-amritsar-boer-war-concentration-camp-mau-mau-a6821756.html

- ↑ https://www.prageru.com/video/if-you-live-in-freedom-thank-the-british-empire/

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HFMG1vmVkTo

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vtNLVPxR67U

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HurC8aTsVCE

- ↑ The British set up a new colony in Hong Kong that became its base for expansion into the China market. Otherwise China remained independent. There were two small colonies on the mainland of Latin America, but they were not very important.

- ↑ See Cain and Hopkins, British Imperialism (2001)

- ↑ Cain and Hopkins (2001); Dumett, 1999

- ↑ Ronald Robinson and John Gallagher with Alice Denny, Africa and the Victorians: The Climax of Imperialism (1968), pp 1-4

- ↑ How big was the British Empire and why did it collapse?, The Week

- ↑ Ian Tyrrell, "Making Nations/Making States: American Historians in the Context of Empire," Journal of American History, Vol. 86, No. 3, (Dec., 1999), pp. 1015-1044 in JSTOR

- ↑ Rajat Kanta Ray, "Indian Society and the Establishment of British Supremacy, 1765-1818," in The Oxford History of the British Empire: vol. 2, The Eighteenth Century" ed. by P. J. Marshall, (1998), pp 508-29

- ↑ Professor Ray agrees that the East India Company inherited an onerous taxation system that took one-third of the produce of Indian cultivators.

- ↑ P.J. Marshall, "The British in Asia: Trade to Dominion, 1700-1765," in The Oxford History of the British Empire: vol. 2, The Eighteenth Century" ed. by P. J. Marshall, (1998), pp 487-507

- ↑ J.R. Ward, "The British West Indies in the Age of Abolition," in P.J. Marshall, ed. The Oxford History of the British Empire: Volume II: The Eighteenth Century (1998) pp 415-39.

- ↑ David Richardson, "The British Empire and the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1660-1807," in P.J. Marshall, ed. The Oxford History of the British Empire: Volume II: The Eighteenth Century (1998) pp 440-64.

- ↑ John Oldmixon, The British Empire in America, Containing the History of the Discovery, Settlement, Progress and Present State of All the British Colonies, on the Continent and Islands of America (London, 1708))

- ↑ As in Nathaniel Crouch, The English Empire in America: Or a Prospect of His Majesties Dominions in the West-Indies (London, 1685). Armitage pp 174-5

Categories: [History] [British History] [Slavery] [Economic History] [Africa] [Asia] [British Empire]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/25/2023 07:12:40 | 443 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/British_Empire | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF