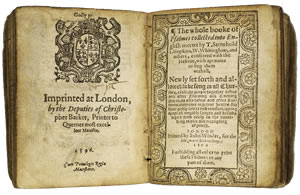

Book Of Common Prayer

From Nwe

From Nwe The Book of Common Prayer is the foundational prayer book of the Church of England and also the name for similar books used in other churches in the Anglican Communion. It replaced the four Latin liturgical books with a single compact volume in English. First produced in 1549 it was drastically revised in 1552 and more subtly changed in 1559 and 1662. It has been substantially replaced in most churches of the Anglican Communion but it is in use in England in a few places and remains, in law, the primary liturgical prayer book of the Church of England. It was introduced during the Protestant Reformation.

The Book of Common prayer is considered to have significantly contributed to the English language. It has been a source of spiritual strength for millions of people, for whom the familiar rhythm and cadence of its beautiful language provides a doorway to the divine presence. Many people continue to use its prayers in private, while following the newer, alternative prayer books in public. Many Anglicans point out that their main book, which binds them together has been called a Book of Common Prayer, not one of doctrine. Praying the same prayers while holding divergent doctrinal views may be one of the chief and most attractive characteristics of the Anglican communion.

History

The Prayer Books of Edward VI

The work of producing English language books for use in the liturgy was, at the outset, the work of Thomas Cranmer Archbishop of Canterbury, under the reign of Henry VIII. Whether it was Cranmer who forced the pace or whether the King was the prime mover is not certain, but Cranmer was in touch with contemporary German reform. Cranmer deserves much credit for giving religious content to the English reformation which had its origin in politics (Henry's desire to divorce his wife). His first work, the earliest English-language service book of the Church of England, was the Exhortation and Litany (1544). This was no mere translation: its Protestant character is made clear by the drastic reduction of the place of saints, compressing what had been the major part into three petitions. Published in 1544, it borrowed greatly from Martin Luther's Litany and Myles Coverdale's New Testament, and was the only service that might be considered to be "Protestant" to be finished within the lifetime of King Henry VIII.

It was not until Henry's death in 1547 and the accession of Edward VI that the reform could proceed faster. Cranmer finished his work on an English Communion rite in 1548, obeying an order of Parliament of the United Kingdom that Communion was to be given as both bread and wine. The service existed as an addition to the pre-existing Latin Mass.

It was included, one year later, in 1549, in a full prayer book[1], set out with a daily office, readings for Sundays and Holy Days, the Communion Service, Public Baptism, of Confirmation, of Matrimony, The Visitation of the Sick, At a Burial and the Ordinal (added in 1550).[2] The Preface to this edition, which contained Cranmer's explanation as to why a new prayer book was necessary, began: "There was never any thing by the wit of man so well devised, or so sure established, which in continuance of time hath not been corrupted". The original version was used until only 1552, when a further revision was released.

The 1549 introduction of the Book of Common Prayer was widely unpopular especially in places such as Cornwall where traditional religious processions and pilgrimages were banned and commissioners sent out to remove all symbols of Roman Catholicism. At the time the Cornish only spoke their native Cornish language and the forced introduction of the English Book of Common Prayer resulted in the 1549 Prayer Book Rebellion. Proposals to translate the Prayer Book into Cornish were suppressed and in total some 4,000 people lost their lives in the rebellion.

The 1552 prayer book marked a considerable change. In response to criticisms by such as Peter Martyr and Martin Bucer deliberate steps were taken to excise Catholic practices and more fully realize the Calvinist theological project in England. In the Eucharist, gone were the words Mass and altar; gone was the 'Lord have mercy' to be replaced by the Ten Commandments; removed to the end was the Gloria; gone was any reference to an offering of a 'Sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving' in the Eucharistic prayer, which ended with the words of institution (This is my Body….This is my blood…). The part of the prayer which followed, the Prayer of Oblation, was transferred, much changed, to a position after the congregation had received communion. The words at the administration of communion which, in the prayer book of 1549 described the Eucharistic species as 'The body of our Lorde Jesus Christe…', 'The blood of our Lorde Jesus Christe…' were replaced with the words 'Take, eat, in remembrance that Christ died for thee…', etc. The Peace, at which in earlier times the congregation had exchanged a greeting, was removed altogether. Vestments such as the stole, chasuble and cope were no longer to be worn, but only a surplice. It was the final stage of Cranmer's work of removing all elements of sacrifice from the Latin Mass. In the Baptism service the signing with the cross was moved until after the baptism and the exorcism, the anointing, the putting on of the chrysom robe and the triple immersion were omitted. Most drastic of all was the removal of the Burial service from church: it was to take place at the graveside. In 1549, there had been provision for a Requiem (not so called) and prayers of commendation and committal, the first addressed to the deceased. All that remained was a single reference to the deceased, giving thanks for their delivery from ' the myseryes of this sinneful world'. This new Order for the Burial of the Dead was a drastically stripped-down memorial service designed to definitively undermine the whole complex of traditional beliefs about Purgatory and intercessory prayer.

Before the book was in general use, however, Edward VI died. In 1553, Mary, upon her succession to the throne, restored the old religion. The Mass was re-established, altars, rood screens and statues were re-instated; an attempt was made to restore the Church to its Roman affiliation. Cranmer was punished for his work in the Protestant reformation by being burned at the stake on March 21, 1556. Nevertheless, the 1552 book was to survive. After Mary's death in 1558,it became the primary source for the Elizabethan Book of Common Prayer, with subtle if significant changes only, and Cranmer's work was to survive until the 1920s as the only authorized book in the Church of England.

The 1559 prayer book

Thus, under Elizabeth, a more permanent enforcement of the Reformed religion was undertaken, and the 1552 book was republished in 1559, along with laws requiring conformity to the new standards. In its Elizabethan form, scarcely altered, it was used for nearly 100 years, thus being the official prayer book under the Stuarts as well as being the first Anglican service in America. This was the prayer book of Queen Elizabeth I, John Donne, and Richard Hooker. It was also at the core of English liturgical life throughout the lifetime of Shakespeare.

The alterations of the 1559 Prayer Book from its 1552 precursor, though minor, were to cast a long shadow. One related to what was worn. Instead of the banning of all vestments save the rochet (for bishops) and the surplice for parish clergy, it permitted 'such ornaments… as were in use… in the second year of K.Edward VI'. This allowed substantial leeway for more traditionalist clergy to retain at least some of the vestments which they felt were appropriate to liturgical celebration. It was also to be the basis of claims in the nineteenth century that vestments such as chasubles, albs and stoles were legal. At the Communion the words 'the Body of our Lord Jesus Christ' etc. were combined with the words of Edward's second book, 'Take eat in remembrance…' etc. The prohibition on kneeling at the Communion was omitted. The conservative nature of these changes underlines the fact that Elizabeth's Protestantism was by no means universally popular, a fact which she herself recognized; her revived Act of Supremacy, giving her the ambiguous title of Supreme Governor passed without difficulty, but the Act of Uniformity passed through Parliament by only three votes.

Still, the 1559 Prayer Book offered enough to both traditionalists and radical reformers to establish it at the heart of the first relatively stable Protestant state in Europe — the "Elizabethan settlement." However, on her death in 1603, this book, substantially the book of 1552, having been regarded as offensive by the likes of Bishop Stephen Gardiner in the sixteenth century as being a break with the tradition of the Western church, as it was, by the seventeenth century had come to be regarded as unduly Catholic. On the accession of James I, following the so-called Millenary Petition, the Hampton Court conference of 1604, a meeting of bishops and Puritan divines, resisted the pressure for change (save to the catechism). By the reign of Charles I (1625-1649) the Puritan pressure, exercised through a much changed Parliament, had increased. Government-inspired petitions for the removal of the prayer book and episcopacy 'root and branch' resulted in local disquiet in many places and eventually the production of locally organized counter petitions. The government had its way but it became clear that the division was not between Catholics and Protestants, but between Puritans and those who valued the Elizabethan settlement. The 1559 book was finally outlawed by Parliament in 1645 to be replaced by the Directory of Public Worship which was more a set of instructions than a prayer book. How widely the Directory was used is not certain; there is little evidence of its having been purchased, in churchwardens' accounts. The Prayer Book certainly was used clandestinely in some places, not least because the Directory made no provision at all for burial services. Following the execution of Charles I in 1649 and the establishment of the Commonwealth under Lord Protector Cromwell, it would not be reinstated until shortly after the restoration of the monarchy to England.

The 1662 prayer book

The 1662 prayer book was printed only two years after the restoration of the monarchy, following the Savoy Conference convened by Royal Warrant to review the book of 1559. Attempts by Presbyterians led by Richard Baxter to gain approval for an alternative service book were in vain. In reply to the Presbyterian Exceptions to the book only fifteen trivial changes were made to the book of 1559. Among them was the inclusion of the Offertory. This was achieved by the insertion of the words 'and oblations' into the prayer for the Church and the revision of the rubric so as to require the monetary offerings to be brought to the Table (instead of being put in the poor box) and the bread and wine placed upon the Table. Previously it was not clear when and how bread and wine were produced. After the communion the unused but consecrated bread and wine were to be reverently consumed in church rather than being taken away and used for any other occasion. By such subtle means were Cranmer's purposes further subverted, leaving it for generations to argue over the precise theology of the rite. Unable to accept the new book 2,000 Presbyterians were deprived of their livings. This revision survives today as the "standard" Parliament-approved Book of Common Prayer in England, with only minor revisions since its publication (mostly due the changes in the monarchy and in the dominion of the former Empire), but few parishes actually use it. In practice, most services in the Church of England are from Common Worship, approved by General Synod in 2000, following nearly 40 years of experiment.

The actual language of the 1662 revision was little changed from that of Cranmer, with the exception of the modernization of only the most archaic words and phrases. This book was the one which had existed as the official Book of Common Prayer during the most monumental periods of growth of the British Empire, and, as a result, has been a great influence on the prayer books of Anglican churches worldwide, liturgies of other denominations in English, and of the English language as a whole.

Further developments

After the 1662 prayer book, development ceased in England until the twentieth century; that it did was, however, a bit of a close run thing. On the death of Charles II his brother, a Roman Catholic, became James II. James wished to achieve toleration for those of his own Roman Catholic faith, whose practices were still banned. This, however, drew the Presbyterians closer to the Church of England in their common desire to resist 'popery'; talk of reconciliation and liturgical compromise was thus in the air. But with the flight of James in 1688 and the arrival of the Calvinist William of Orange the position of the parties changed. The Presbyterians could achieve toleration of their practices without such a right being given to Roman Catholics and without, therefore, their having to submit to the Church of England, even with a liturgy more acceptable to them. They were now in a much stronger position to demand even more radical changes to the forms of worship. John Tillotson, Dean of St. Paul's pressed the king to set up a Commission to produce such a revision The so-called Liturgy of Comprehension of 1689, which was the result, conceded two thirds of the Presbyterian demands of 1661; but when it came to Convocation the members, now more fearful of William's perceived agenda, did not even discuss it and its contents were, for a long time, not even accessible. This work, however, did go on to influence the prayer books of many British colonies.

By the nineteenth century other pressures upon the book of 1662 had arisen. Adherents of the Oxford Movement, begun in 1833, raised questions about the relationship of the Church of England to the apostolic church and thus about its forms of worship. Known as Tractarians after their production of 'Tracts for the Times' on theological issues, they advanced the case for the Church of England being essentially a part of the 'Western Church', of which the Roman Catholic Church was the chief representative. The illegal use of elements of the Roman rite, the use of candles, vestments and incense, practices known as Ritualism, had become widespread and led to the Public Worship Regulation Act 1874 which established a new system of discipline, intending to bring the 'Romanisers' into conformity. The Act had no effect on illegal practices: five clergy were imprisoned for contempt of court and after the trial of the saintly Bishop Edward King of Lincoln, it became clear that some revision of the liturgy had to be embarked upon. Following a Royal Commission report in 1906, work began on a new prayer book, work that was to take twenty years.

In 1927, this proposed prayer book was finished. It was decided, during development, that the use of the services therein would be decided on by each given congregation, so as to avoid as much conflict as possible with traditionalists. With these open guidelines the book was granted approval by the Church of England Convocations and Church Assembly. Since the Church of England is a state church, a further step—sending the proposed revision to Parliament—was required, and the book was rejected in December of that year when the MP William Joynson-Hicks, 1st Viscount Brentford argued strongly against it on the grounds that the proposed book was "papistical" and insufficiently Protestant. The next year was spent revising the book to make it more suitable for Parliament, but it was rejected yet again in 1928. However Convocation declared a state of emergency and authorized bishops to use the revised Book throughout that emergency.

The effect of the failure of the 1928 book was salutary: no further attempts were made to change the book, other than those required for the changes to the monarchy. Instead a different process, that of producing an alternative book, led eventually to the publication of the 1980 Alternative Service Book and subsequently to the 2000 Common Worship series of books. Both owe much to the Book of Common Prayer and the latter includes in the Order Two form of the Holy Communion a very slight revision of the prayer book service altering only one or two words and allowing the insertion of the Agnus Dei (Lamb of God) before Communion. Order One follows the pattern of modern liturgical scholarship.

In 2003, a Roman Catholic adaptation of the BCP was published called the Book of Divine Worship. It is a compromise of material drawn from the proposed 1928 book, the 1979 Episcopal Church in the United States of America (ECUSA) book, and the Roman Missal. It was published primarily for use by Catholic converts from Anglicanism within the Anglican Use.

Prayer books in other Anglican churches

A number of other nations have developed Anglican churches and their own revisions of the Book of Common Prayer. Several are listed here:

USA

The Episcopal Church in the United States of America has produced numerous prayer books since the inception of the church in 1789. Work on the first book began in 1786 and was subsequently finished and published in 1789. The preface thereto mentions that "this Church is far from intending to depart from the Church of England in any essential point of doctrine, discipline, or worship… further than local circumstances require," and the text was almost identical to that of the 1662 English book with but minor variations. Further revisions to the prayer book in the United States occurred in 1892, 1928, and 1979. The revisions of 1892 and 1928 were minor; the version of 1979 reflected a radical departure from the historic Book of Common Prayer, and led to substantial controversy and the breaking away of a number of parishes from the ECUSA. Each edition was released into the public domain on publication, which has contributed to its influence as other churches have freely borrowed from it. The typeface used for the book is Sabon.

Australia

The Anglican Church of Australia has successively issued several local versions of the Book of Common Prayer. The current edition is A Prayer Book For Australia (1995). The extreme theological divergence between Australia's largest and most prosperous diocese, the deeply conservatively evangelical Diocese of Sydney, and the rest of the Australian church has not proved as problematic for prayer book revisers as one might have supposed, as Sydney frowns on prayer books, as it does other conventionally Anglican appurtenances such as communion tables, robed clergy, and chanted and sung liturgies.

Canada

The Anglican Church of Canada developed its first Book of Common Prayer separate from the English version in 1918. A revision was published in 1962, largely consisting of minor editorial emendations of archaic language (for example, changing "O Lord save the Queen/Because there is none other that fighteth for us but only thou O Lord" to "O Lord save the Queen/And evermore mightily defend us"). This edition is considered the last Anglican Prayer Book (in the classic sense, though some churches, such as the USA and Ireland, have named their contemporary liturgies "Prayer Books"). Some supplements have been developed over the past several years to the prayer book, but the compendious Book of Alternative Services, published in 1985, which inter alia contains rites couched in Prayer Book phraseology, has largely supplanted it.

Scotland

The Scottish Episcopal Church has had a number of revisions to the Book of Common Prayer since it was first adapted for Scottish use in 1637. These revisions were developed simultaneously with the English book till the mid-seventeenth century when the Scottish book departed from the English revisions. A completely new revision was finished in 1929, and several revisions to the communion service have been prepared since then.

Papua New Guinea

The Anglican Church of Papua New Guinea, separated from the ecclesiastical province of Brisbane in 1977 after Papua New Guinea's independence from Australia, contends with the unusual problem that its adherents are largely concentrated in one province, Northern, whose inhabitants are largely Orokaiva speakers, little acquainted with the country's largest lingua franca, New Guinea Pidgin. However, there are pockets of Anglicans elsewhere in the country including in the New Guinea Highlands and the New Guinea Islands, areas where Pidgin is used, as well as foreigners who use English in the towns. The Anglican Province has settled on a simple-English prayer book along the lines of the Good News Bible, including simple illustrations.

Religious influence

The Book of Common Prayer has had a great influence on a number of other denominations. While theologically different, the language and flow of the service of many other churches owes a great debt to the prayer book.

John Wesley, an Anglican priest whose teachings constitute the foundations of Methodism said, "I believe there is no Liturgy in the world, either in ancient or modern language, which breathes more of a solid, scriptural, rational piety than the Common Prayer of the Church of England." Presently, most Methodist churches have a very similar service and theology to those of the Anglican Church. The United Methodist Book of Worship (1992, ISBN 0687035724) uses the Book of Common Prayer as its primary model.

In the 1960s, when Roman Catholicism adopted a vernacular mass, many translations of the English prayers followed the form of Cranmer's translation. Indeed, a number of theologians have suggested that the later English Alternative Service Book and 1979 American Book of Common Prayer borrowed from the Roman Catholic vernacular liturgy.

Secular influence

On Sunday July 23, 1637 efforts by King Charles I to impose Anglican services on the Church of Scotland led to the Book of Common Prayer revised for Scottish use being introduced in Saint Giles' Cathedral, Edinburgh. Rioting in opposition began when Dean John Hanna began to read from the new Book of Prayer, legendarily initiated by the market-woman or street-seller Jenny Geddes throwing her stool at his head. The disturbances led to the National Covenant and hence the Bishops' Wars; the first part of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which included the English Civil War. The National Covenant pledged that Scotland would retain the non-episcopal church order and oppose Catholicism.

Together with the King James Version of the Bible and the works of William Shakespeare, the Book of Common Prayer has been one of the three fundamental underpinnings of modern English. As it has been in regular use for centuries, many phrases from its services have passed into the English language, either as deliberate quotations or as unconscious borrowings. They are used in non-liturgical ways. Many authors have used quotes from the prayer book as titles for their books.

Some examples are:

- "Speak now or forever hold your peace" from the Marriage liturgy.

- "Till death us do part" (often misquoted as "till death do us part"), from the marriage liturgy.

- "Earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust" from the Funeral service.

Copyright status

In most of the world the Book of Common Prayer can be freely reproduced as it is long out of copyright. This is not the case in the United Kingdom itself.

In the United Kingdom, the rights to the Book of Common Prayer are held by the British Crown. The rights fall outside the scope of copyright as defined in statute law. Instead they fall under the purview of the royal prerogative and as such they are perpetual in subsistence. Publishers are licensed to reproduce the Book of Common Prayer under letters patent. In England, Wales and Northern Ireland the letters patent are held by the Queen's Printer, and in Scotland by the Scottish Bible Board. The office of Queen's Printer has been associated with the right to reproduce the Bible for many years, with the earliest known reference coming in 1577. In England, Wales and Northern Ireland the Queen's Printer is Cambridge University Press. CUP inherited the right of being Queen's Printer when they took over the firm of Eyre & Spottiswoode in the late twentieth century. Eyre & Spottiswoode had been Queen's Printer since 1901. Other letters patent of similar antiquity grant Cambridge University Press and Oxford University Press the right to produce the Book of Common Prayer independently of the Queen's Printer.

The terms of the letters patent prohibit those other than the holders, or those authorized by the holders from printing, publishing or importing the Book of Common Prayer into the United Kingdom. The protection that the Book of Common Prayer, and also the Authorized Version, enjoy is the last remnant of the time when the Crown held a monopoly over all printing and publishing in the United Kingdom.

It is common misconception that the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office holds letters patent for being Queen's Printer. The Controller of HMSO holds a separate set of letters patent which cover the office Queen's Printer of Acts of Parliament. The Scotland Act 1998 defines the position of Queen's Printer for Scotland as also being held by the Queen's Printer of Acts of Parliament. The position of Government Printer for Northern Ireland is also held by the Controller of HMSO.

Notes

- ↑ The Long title of the English Book of Common Prayer is The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church according to the use of the Church of England together with the Psalter or Psalms of David pointed as they are to be sung or said in churches and the form and manner of making, ordaining, and consecrating of bishops, priests, and deacons

- ↑ The Supper of the Lord and Holy Communion, Commonly called the Mass. [1]. Retrieved June 20, 2008.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Booty, John E. The Book of common prayer, 1559 : the Elizabethan prayer book. Charlottesville, VA : Published for the Folger Shakespeare Library by the University of Virginia Press, 2005. ISBN 0813925177

- Fawcett, Timothy J. The Liturgy of Comprehension 1689. Southend-on-Sea, Mayhew-McCrimmon Ltd [for] the Alcuin Club, 1973. ISBN 0855970316

- Forbes, Dennis, Did the Almighty intend His book to be copyrighted?, European Christian Bookstore Journal, April 1992

- Francis, Frere Walter Howard Procter A New History of the Book of Common Prayer MacMillan and Co, Ltd., 1941. ASIN B0007J8S0S

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid. The Boy King: Edward VI and the Protestant Reformation Berkeley : University of California Press, 2002. ISBN 0520234022

- Maltby, Judith D. Prayer Book and People in Elizabethan and Early Stuart England Cambridge, U.K.; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 0521793874

External links

All links retrieved February 8, 2022.

- Collection of BCP resources

- 1662 Book of Common Prayer

- 1928 Book of Common Prayer

- 1979 Book of Common Prayer

- The Book of Common Prayer of the Church in Wales

- Everyman's History of the Prayer Book

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 22:53:15 | 20 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Book_of_Common_Prayer | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF