World History Lecture Four

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia 1-2-3-4-5-6-7-8-9-10-11-12-13-14

The Roman empire was the last great ancient civilization, stronger than the Greeks in government but weaker in philosophy. The Roman empire brought the world Latin, good roads, the brutal persecution of early Christians and, ultimately, the acceptance and expansion of Christianity. The discussion of the Roman empire in this lecture completes our review of the ancient world.

The Roman Empire[edit]

Around 2000 B.C., Indo-Europeans settled the Italian peninsula where modern-day Italy is located. Recall that "Indo-Europeans" is a very general classification that includes peoples stretching all the way from India to Europe, who spoke any of dozens of Indo-European languages, including Sanskrit in India, Persian in the Middle East, Slavic in Eastern Europe and Germanic, Italic and Celtic languages in Europe. Like the ancient and classical Indian civilization, the Roman empire traced its roots to Indo-Europeans.

The Beginnings of the Roman Republic[edit]

The Roman empire received its name from its western capital, Rome, which was the first city of the empire, dating back as early as the 8th century B.C. Dorians had invaded Greece around 1000 B.C. and forced it into a Dark Age; some Greeks fled to the Italian peninsula and named the region "Italy". By legend, in 753 B.C. two brothers named Romulus and Remus founded the city of Rome on the Tiber River, 15 miles inland from the Tyrrhenian Sea of the Mediterranean Sea. According to legend, the boys were descendants of Aeneas, who was a refugee of the mythical Trojan War featured in the masterpiece of Greek literature, The Iliad, and their father was the god Mars. Abandoned as babies and thrown into the Tiber River by their jealous uncle, the boys were rescued and raised by a mother wolf who had lost her cubs.

When Romulus and Remus were grown, they killed their uncle and founded a city. Each wanted the new city to be in a different location, and in the fight that ensued, Romulus killed his brother Remus and the city was named Rome. This story illustrates well the violence and cruelty that was to become a defining characteristic of the Roman people.

In 700 B.C. the Etruscans conquered Rome, and King Etruscan ruled it like the city-states in Greece. The Etruscans had a huge influence on the Italian peninsula, and many of their hobbies (e.g., chariots), architectural forms (e.g., the arch), and beliefs (e.g., the primary Roman gods and goddesses were Jupiter, Juno and Minerva, later worshiped by the Romans) remained influential for thousands of years. Some Greeks migrated to the Italian peninsula also. To the Etruscans, Rome was just another small city-state then.

Landowners revolted and began establishing a republic over the entire region, without any city-states. In 509 B.C., the Roman Republic was formed. After overthrowing the Etruscan king, Roman soldiers conquered the Etruscan city-states one-by-one. By 250 B.C., Romans had taken over every previously Etruscan-ruled territory.

Early Roman society had two classes of people: patricians (wealthy landowners) and plebeians (small farmers and shopkeepers). Today a "plebe" is the word used to describe a lowly freshman at a U.S. military academy like West Point.)

The patricians comprised only 10% of the society, but held most of the power through their 300-member Senate. Senators served for life and made decisions about war and peace, and proposed laws to govern the country. Proposed laws required approval by the Assembly of Centuries, which was composed of all-male soldiers, organized in units of 100 each, or centuries. At the head of the republic were two consuls, elected from the patrician class. The consuls ran the army and managed religious functions. They could veto each other and even turn their power over to a dictator for a maximum of six months. Citizenship was typically not offered to people in conquered lands.

Before long the plebes began to demand more rights for themselves. They refused to serve in the army, and the Senate appeased plebes by granting them the right to elect representatives, or "tribunes". The election of these tribunes occurred at a gathering of plebes called the Assembly of Tribes, which passed resolutions that the tribunes could present for ratification by the Senate. The Tribal Assembly could also veto some laws. The patrician monopoly on important positions was further weakened when intermarriage between plebes and patricians was legalized for the first time in 445 B.C. The Republic received a setback when Rome was sacked by Gaul (modern France) in 390 B.C. Afterward, beginning in 376 B.C. plebes could serve in the consuls, and by 287 B.C. patricians could participate in the Assembly of Tribes. Class differences began to disappear and Roman society became more democratic.

Two ingredients made Rome a great empire: Roman law and Roman legions. Your instructor emphasizes a third ingredient: Latin, the Roman language, was a very powerful, effective means of communicating. This language enabled powerful concepts to be expressed succinctly, and often Latin phrases are used today in the legal system, science, and elsewhere. Concepts that require sentences to be described in English can be expressed in just a few words in Latin, such as "caveat emptor" (meaning "the burden of examining a product or service is on the buyer before he pays his money, and it is up to him alone to make sure that he gets as much in value as he pays"; more literally, "caveat emptor" means "let the buyer beware").

Roman Law developed in a rational and flexible manner, though obviously it failed to provide justice during the trial of Jesus, who was not a Roman citizen. Roman Law began with a code of laws inscribed in the Twelve Tables around 450 B.C. "Twelve" is an easy number to remember: it's the same number of ancient tribes in Israel. But this is merely a coincidence.

Judges (elected "praetors") interpreted and applied the Twelve Tables in various locations, using local customs and precedents. This was the origin of the concept of "civil law," expressed in Latin as "jus civile." Roman law thereby became flexible and powerful in a way never seen before. The concept of "justice" developed whereby laws, not whim, governed society. Judgments were to be entered based only on evidence presented pursuant to established procedures, and people learned to respected the law through use of a symbol representing notions of justice: Justitia, the Roman goddess of justice, who wore a blindfold and held scales in one hand and a sword in the other. Rights were established for citizens and also for women and slaves. Foreign law was addressed through "jus gentium," or "law of nations," which handled conflicts between Rome and distant locations. Often judges would invoke the concept of universal law, or "jus naturale," to decide controversies. Roman law valued private property and the central role played by families, and these priorities helped hold the vast empire together. Influence of Roman law is seen in many instances in America today, from the concept that all citizens are equal under the law to the principle of "innocent until proven guilty." A great body of law that helped protect the underprivileged was codified as "Justinian's Code" in the A.D. 500s. Along with the benefits of a single currency (coins) for commercial transactions, a common legal system was a major reason for the enormous success of the Roman empire.

As important as Roman law was, the Roman military was even more influential. Every physically capable male Roman was required to serve in the army. Roman soldiers were unstoppable. Roman "legions" consisted of 3000 to 6000 soldiers, well-equipped with armor that included shields, helmets, swords and even javelins. The Roman soldiers were considered nearly invincible and could easily defeat the Greeks. In 272 B.C., the Roman army crushed the army of Pyrrhus, the king of Epirus, who attempted to defend Greek cities in southern Italy. By 265 B.C., the Romans controlled all of Italy except for the Po Valley.

The Punic Wars[edit]

Rome fought and won a series of important wars known as the Punic (PYOO-nik) Wars, between 264 and 146 B.C. against the Phoenician city of Carthage on the southern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. This enabled the Roman Republic to gain control of the Mediterranean Sea and exclusive control over the trade of wine, olive oil, food and many other goods. There were three Punic Wars in all, named "Punic" after the Roman term for Phoenician.

In the First Punic War (264-241 B.C.), Rome conquered the island of Sicily and acquired its grain-producing territory. Rome developed a navy as a result of this war. With no previous knowledge of shipbuilding, the Roman ships were at first no match for the powerful Carthaginian navy. But the invention of the "corvus" (a hook-like device by which the Romans could attach their ships to Carthaginian ships) allowed the Romans to board enemy ships, and thereby gaining the advantage with their superior hand-to-hand combat.

In the Second Punic War (218-202 B.C.), Rome fought against the military genius named Hannibal. Hannibal, the leader of Carthage, took his entire army through Spain and then, in a preemptive move, crossed the Italian Alps in merely 15 days to the great surprise of the Romans. Hannibal's crossing of the Alps with 30,000 men and some elephants is considered one of the greatest military feats of the ancient world. He then beat the Romans in a series of battles lasting 16 years but could not conquer Rome itself. Hannibal had to retreat to Africa when the Romans attacked Carthage. Rome acquired Spain as a result of the Second Punic War.

In the Third Punic War, the Romans destroyed Carthage (146 B.C.), killing its inhabitants or taking them as slaves. Then the vicious Romans spread salt over all the Cathaginian farms to make it impossible to grow crops. The Romans then went into Macedonia and Greece to defeat the region in revenge for having helped Hannibal. By the end, Rome controlled all the land around the Mediterranean Sea, which was the entire western civilized world at that time. The Roman senator Cato the Elder encouraged Rome's terrible revenge by ending every speech with the conclusion, Carthago delenda est: "Carthage must be destroyed." The Roman soldiers returned home with their winnings, and with Greek knowledge. Rome itself became Hellenistic, fascinated by the culture of the Greeks, including their architecture, their language, and their system of justice. The Roman empire helped spread Greek knowledge further than the Greeks themselves could.

Leading up to an Empire[edit]

In the eastern Mediterranean, Rome fought wars in Anatolia (present-day Turkey) and Macedonia between 215 and 148 B.C. to gain control over those territories. By 148 B.C., Rome controlled everything around the Mediterranean from Spain to Anatolia.

Afterward a period of struggle ensued between the Roman military, fresh from its conquests, and the Roman Senate, which ruled using a republican form of government. Some corruption followed, and historians blame wealthy senators for blocking some economic proposals.

The Gracchi brothers, Tiberius and Gaius, served as tribunes in 133 and 123 B.C., respectively. They passed laws to help the poor by redistributing land to the poor from the wealthy estates, known as "latifundia". Gaius tried to end the practice of wheat speculation, by which wealthy citizens bought all the grain available and then, during times of shortage, resold it to the poor at greatly inflated prices. However, the angry Senate instigated a riot that clubbed Tiberius to death in 133 B.C., and his brother Gaius committed suicide before he could be assassinated for trying to resell grain to the poor at low prices in 121 B.C.

Finally, near the beginning of the first century B.C., a general named Gaius Marius was elected consul. He came up with the idea of Rome's first professional army, and substituted it for the prior system by which only landholding citizens could serve in the military. Marius hired landless citizens for long terms and quickly gained support from his well-paid army. But soon a civil war broke out between the Senate (which supported Marius) and the General Assembly (which supported a general named Cornelius Sulla). Finally, Sulla took power, executed Marius's followers, and pretended to reestablish the power of the Senate in 83 B.C. But in effect Sulla ruled as another dictator until Spartacus, a Greek slave, led a bloody slave revolt.

Julius Caesar[edit]

Order was not established again until one of the greatest leaders and military minds in the history of the world finally emerged to take control. Julius Caesar (100-44 B.C.) was a brilliant general who laid the groundwork for the Roman empire. In 60 B.C. Julius Caesar joined with two others -- the wealthy Marcus Crassus and the powerful Roman general and statesman Pompey the Great -- to rule Rome as the first triumvirate. In 59 B.C. Julius Caesar became consular and used his position to gain favor with the public by, for example, distributing grain to the poor.

Julius Caesar then made himself the provincial ruler (proconsul) of Gaul (modern-day France). He conquered vast amounts of territory for Rome and, while fighting abroad, sent written reports back to Rome of the victories he was winning, to sustain his popularity and to ensure that the people did not forget him. Back in Rome, Julius Caesar's plan was working, and Pompey became increasingly jealous (by this time, Crassus had died in battle). Pompey, with the support of the Senate, objected to Julius Caesar's actions and ordered him to disband his army and return to Rome. But Julius Caesar refused; in an act of direct defiance to the Senate, he then led his loyal troops across the Rubicon River to Rome and conquered it in 49 B.C. The expression "crossing the Rubicon" is used today to describe an act from which there is no turning back. Julius Caesar went on to defeat Pompey at the battle of Pharsalus in 48 B.C. This left Julius Caesar firmly in control of Rome, and he then took his unbeatable army on campaigns in Egypt (where he installed ally Cleopatra as queen), Asia Minor, Africa and Spain before returning to Rome again in 45 B.C. Rome ruled much of the civilized world as result of these military campaigns, and the Roman Senate appointed Julius Caesar as dictator for life in 46 B.C.

Julius Caesar instituted the 12-month, 365-day "Julian Calendar," which provided the foundation for the "Gregorian Calendar" adopted later by a pope and used to this day. Julius Caesar also granted religious rights to the Jews in Palestine, so that the Jewish religion could be practiced outside the requirements of Roman religious law, which continued through the time of Christ. In addition, Julius Caesar was also good to veterans (former soldiers) and the poor.

The Roman Senate did not like losing power to the dictator Julius Caesar. In a conspiracy famously recounted in Shakespeare's play entitled Julius Caesar, Cassius and Brutus and up to 60 others agreed to stab and kill Julius Caesar when he entered the Senate on the "Ides of March" (March 15, 44 B.C.). After he died, Rome fell into chaos for 13 years as rivals strove for power. Julius Caesar had wanted his 18-year-old grandnephew, Gaius Octavius, to be his heir and become emperor. Others wanted Mark Antony. Cassius and Brutus also had armies of their own. A triumvirate of Octavian, Antony and Lepidus defeated the armies of Cassius and Brutus, and that ended the republican rule by the Roman Senate.

But then the triumvirate fought internally among each other. Lepidus retired. Antony fell in love with Cleopatra, queen of Egypt, and went to be with her there, ruling the eastern part of the empire. To turn public opinion against the popular Antony, Octavian read aloud a paper to the Senate that was supposedly Antony's will. In it, Antony expressed his intent for Cleopatra and her children to rule the eastern part of the Empire after his death. At the Battle of Actium in 31 B.C., Antony and Octavian clashed and Octavian won. Antony and Cleopatra fled back to Egypt, but Octavian's army hunted them down. Rather than be captured or killed, they took their own lives. Their affair was chronicled over a thousand years later by Shakespeare in his tragedy, Antony and Cleopatra. After their deaths, Octavian became the sole ruler of the Roman civilization.

Roman culture flourished under Julius Caesar and the struggle afterward. Most notably, Marcus Cicero (106-43 B.C.) became the leading writer, orator and statesman. His works are read to this day in Latin courses, as he established a high standard for Latin prose. But there was no freedom of speech in ancient Rome, and when Cicero's work named The Philippics criticized Mark Antony in 43 B.C., Antony responded by putting Cicero to death.

Birth of the Roman Empire[edit]

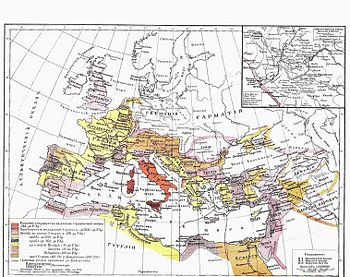

In 27 B.C. Octavian struck a deal to share power with the Roman Senate, with the Senate bestowing on Octavian the name "Augustus" (a term usually used in reference to the gods). The power shared with the Roman Senate was mostly an illusion, however, as Augustus became the dictator, chief priest, and "imperator", a title which meant he had complete control of the army. This was the official birth of the Roman empire, which covered vast, previously conquered territory (see right). Augustus ruled from 27 B.C. to A.D. 14, including the time of the birth of Jesus Christ.

Augustus established a constitutional monarchy rather than a true republic, because the Senate's role became only advisory. Yet under this system of government the Roman empire thrived for 200 years, with the population of Rome growing to more than one million persons by about A.D. 100, a huge number for the ancient world. The Roman empire included far more than 100 cities, which had their own local governments, and which engaged in trade with each other. Eventually, a plague and economic disaster began to cause decreases in the populations of cities by about A.D. 200, and barbarian invasions caused more to flee to the countryside. By the 6th century A.D. the population of Rome had declined to less than 50,000 people. The broadest dates assigned to the Roman empire are from 509 B.C. to A.D. 476, when the last emperor was deposed (removed from power). The greatest time period for the Roman empire was from 27 B.C. to A.D. 180 (known as "Pax Romana," as described later).

The Roman empire is known for its organization and practical benefits for its citizens: great roads, drinking water, currency, laws, powerful military, useful sewers and the orderly administration of justice. Massive in geography, the Empire extended all along the Mediterranean Sea and brought civilization to vast tracts of land and many peoples. The "Silk Road" connected the Roman empire to Parthia (Persia or modern Iran), China and India, thereby facilitating trade. The Roman empire also established a language and alphabet that is the basis for the modern languages and the writings of Western Europe and the United States. After initially persecuting Christians, the Roman empire helped Christianity expand and flourish. Summed up in one word, the Roman empire was "organized".

The Roman empire flourished during "Pax Romana," which is Latin for "the Roman peace." This is the period from 27 B.C. (when Augustus Caesar declared an end to the civil war) to A.D. 180 (when the philosopher-emperor Marcus Aurelius died). During this period the Roman empire generally enjoyed peace, leadership by the "Five Good Emperors," and substantial prosperity. Several of the emperors during this period were chosen for their talent rather than their family connections, such Nerva, who was elected by the Roman Senate. Nerva was then followed by four other talented emperors: Trajan (who ruled over more land than anyone), Hadrian (who built defensive walls), Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius. The last of the Good Emperors, Marcus Aurelius, was a philosopher who wrote a book about spirituality called "Meditations", which emphasized one's personal duty. But he should have given more thought to his successor, because his death in A.D. 180 marked the end of Pax Romana. Chaos followed and the military then fought over who would be the next emperor.

During Pax Romana, the Roman empire governed a vast region extending throughout Western Europe and all the lands around the Mediterranean Sea, including Asia Minor, the Middle East (including Jerusalem), and Northern Africa. Emperor Claudius, who was in power from A.D. 41 to 54, even conquered what is now England, and added it to the Roman empire, leaving behind improved architecture and ideas which allowed England to become powerful during the Middle Ages. The Pax Romana was not entirely peaceful, as there were some wars and conflicts, such as wars against the Germanic tribes and Persians, and turmoil in Jerusalem around the time of Christ. But there were no major civil wars, as there had been for much of the first century B.C., and no major invasions by foreigners into the Roman empire.

The Roman economy thrived during this time. The cities (such as Rome) had good sewage systems and theaters. Water was brought in from mountains by cleverly designed aqueducts. Roads were improved and were quite good, even by today's standards. There was a common currency (coins) accepted throughout the empire. Wealthy Romans even had central heating systems in their houses. There was one set of laws for the entire empire. The great Roman poet Virgil wrote The Aeneid, which was a fictional story about how Rome was founded and the Roman counterpart to the Greek classics of The Iliad and The Odyssey. Historical accounts were written by Tacitus (Annals concerned public virtue and Germania concerned the Germanic tribes on the border of the Roman empire), by Livy (who wrote a history of Rome) and by Plutarch (biographies). Poetry was written by Ovid (Metamorphoses). Satires were written by Horace. Philosophy was written by Seneca on morals. Latin was the language used by teachers, writers, lawmakers, and the Catholic Church in its liturgy.

The Roman provinces, such as Gaul and Spain, did well during this period also. The Roman government built roads, schools and cities for them and constructed aqueducts and sewers. A citizen in these provinces enjoyed the right to appeal to the emperor a decision by a provincial governor installed by Rome.

The uniform law was quite fair, even by modern standards. Women could own property, for example. The accused were supposedly guaranteed legal protection, and an accused was innocent until proven guilty. Obviously this did not occur in the trial of Jesus, however, so there was no guarantee against injustices. But in theory, all citizens were equal in the eyes of the law, though not everyone (including Jesus) was a citizen.

There were multiple ways to obtain citizenship. Latins living along the Tiber River were automatically given citizenship. Others had to enlist in the Roman army for 25 years to earn it. Paul of Taurus obtained his Roman citizenship by birth to parents who were Roman citizens. He used his citizenship to invoke his right to appeal to Caesar in Acts 23:31-26:32.

Historians, however, criticize huge differences between how the rich and poor lived in Rome. Wealthy Roman citizens enjoyed luxurious homes with private gardens, baths and even country estates. Banquets and entertainment were held frequently for the wealthy, and they enjoyed watching brutal boxing matches to the death between gladiators, and even chariot racing, in the Colosseum. Criminals, Christians and slaves were forced to fight vicious animals and be killed by them. Meanwhile, the poor lived in cramped wood apartment houses and in small rooms above shops, and often perished in fires.

Roman Emperors[edit]

Augustus, known until 27 B.C. as Octavian, was the first Roman Emperor and the ruler when Jesus was born in Bethlehem in Judea around 4 B.C. Augustus ruled until his death in A.D. 14, whereupon the Roman Senate appointed Augustus's adopted son Tiberius as the next emperor, the first in a line of Augustus's successors known as the "Julio-Claudian" emperors.

When Augustus became emperor, he established the praetorians to protect the Roman general ("praetor") and the emperor. These elite, well-trained and privileged troops served as a kind of secret police, having more power than the Secret Service does today in protecting the president of the United States. It became essential to gain the support of the praetorians in order to hold high office in government. Constantine later abolished the praetorians in the early A.D. 300s.

Tiberius ruled from A.D. 14-37, and thus was the emperor when Jesus was scourged (whipped) and crucified, barbaric treatment that was prohibited against Roman citizens. Tiberius had previously served a distinguished military career, and at first was a competent ruler extending the earlier policies of his stepfather Augustus. But increasingly Tiberius became paranoid, and ruled more and more like a tyrant. He oversaw many trials for treason and executions, and then left Rome itself in A.D. 26 to retire in Capri, where he was when Jesus was crucified.

The trial of Jesus revealed that while the Roman empire was tremendous in its military, there was much that it lacked in terms of understanding. Pontius Pilate, like most Romans, had no understanding or appreciation of the concept of objective truth. "Therefore Pilate said to Him, 'So You are a king?' Jesus answered, 'You say correctly that I am a king. For this I have been born, and for this I have come into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone who is of the truth hears My voice.' Pilate said to Him, 'What is truth?'"[1] Pilate then left without giving Jesus the opportunity to teach him about truth. In the Roman empire, "truth" did not exist; it was merely whatever the emperor or Roman army said it was. Intellectual progress in the Roman empire was small in comparison to the achievements of Ancient Greece.

Roman leadership weakened immediately following Tiberius. Caligula (A.D. 37-41) was the next emperor, and he was a somewhat insane and highly immoral tyrant whose reign ended in assassination by his own guards, a fate that would greet many despotic Roman emperors. His corrupt rule, which was one of the worst in all of history, can be best remembered as the first emperor to be installed after the crucifixion of Christ. At one point Caligula made his favorite horse a consul. In A.D. 39 he removed the consuls without even consulting with the Senate, because the Senate had not gone along with something he wanted to do. Then he publicly humiliated senators by forcing several of them to trot beside his chariot in public while wearing their full robes. Caligula even planned to impose and install a statue of himself as Zeus in the holiest part of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem, which would have been the worst insult imaginable to the Jewish faith. His reign of terror came to an end when he was assassinated by one of his own guards, fulfilling Jesus's teaching that "he who lives by the sword dies by the sword." When news of Caligula's death reached the public, they were afraid to show their joy lest it only be a rumor invented by Caligula himself that he might punish anyone who dared celebrate upon his death.

Caligula's successor was his uncle Claudius, chosen by the guards who had killed Caligula. Some believe the only way Claudius lived through Caligula's rule was by feigning insanity. Much to everyone's surprise, Claudius proved to be a wise and able ruler and, under his rule, Britain became part of the Roman Empire. Shortly after becoming emperor, however, Claudius died from poisoned mushrooms given to him by his wife so that her son Nero could be king.

Nero was one of the most despised rulers of all time, and was an even more merciless persecutor of the growing numbers of Christians than Caligula had been. Nero became emperor at age sixteen, and despite being taught by the great philosopher Seneca, he quickly became a ruthless and irresponsible leader, ordering the murders of his wife and mother and instructing his teacher Seneca and the poet Lucan to commit suicide. When Rome experienced a ravaging fire in A.D. 64, Nero supposedly sat carelessly playing his fiddle and singing about the fall of Troy. Nero was initially blamed for the fire; however, another rumor to scapegoat Christians quickly began circulating: that Christians had somehow started the fire. Nero responded by embarking on one of the most terrible executions of Christians the world has ever seen. He had men, women and children put into the arena and eaten alive by wild animals. Christians were tarred, tied to tall bundles of sticks and burned alive — human torches to provide light. Peter and Paul were probably killed during Nero's reign. Nero finally killed himself in A.D. 69, much to the relief of Christians and Romans alike.

After Nero's death, the first plebian (common man) emperor in Rome's history rose to power: the wise and practical Vespasian, the first in the line of the "Flavian" emperors. His son Titus ruled after him, and it was during Titus's reign that Rome experienced three disasters: destructive fires, a terrible plague, and the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius, which completely destroyed the cities Herculaneum and Pompeii. Vespasian's other son, Domitian, ruled next and was the last of the Flavian emperors. Next, the "Five Good Emperors" ruled: Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antonious Pius, and lastly, Marcus Aurelius.

Known as the "philosopher king," Marcus Aurelius wrote Meditations, a Stoical work expressing compassion for the weak and less fortunate and resignation to one's fate. During his reign, he led his powerful army against the Germanic tribes in the north, which had become a threat to the Roman empire. Before this job was finished, however, he fell ill and died in A.D. 180, leaving the job to his son Commodus. Lazy and much less capable than his father, Commodus preferred to stay in Rome, and made peace with the Germanic tribes, a decision that would eventually contribute to the destruction of the Roman empire.

Diocletian, who ruled from A.D. 284 to 305, attempted to save the Roman empire by dividing it into eastern and western regions, with Byzantium as the capital of the East and Rome as the capital of the West. He established the "tetrarchy", or division of power among four rulers in A.D. 293. The tetrarchy included two primary rulers, each with the title "Augustus", who ruled over the eastern and western empires, and two "Caesars" who served under the Augustuses. Diocletian imposed economic regulations, some of which seem silly today. For example, Diocletian required farmers to stay with their land and workers to stay on the job for the rest of their lives. He did this to prevent people from leaving their work to avoid taxation. For an empire that used slavery, this probably seemed like normal regulations. Diocletian also imposed wage and price controls to halt inflation. That economic regulation, which almost always fails, is still attempted by modern governments, including even the United States during World War II and by President Nixon in the early 1970s.

Diocletian attempted to suppress Christianity by ordering Christians to worship him and brutally persecuting them when they did not. He was the last emperor to do this. Diocletian abdicated (resigned) in A.D. 305.

Roman Contributions[edit]

The Roman civilization began as part of Hellenism from the Greek empire, but the Romans had their own major contributions in engineering (roads and aqueducts), law, the military, and eventually the spread of Christianity. Roman architecture developed the use of cement and the large arches, domes and vaults, as implemented in the Pantheon (not to be confused with the Parthenon, which was Greek) and the Arch of Constantine. Roman art used mosaics. Latin, the great language of the Roman empire, formed the basis for the "romance" languages of Europe still in use today: French, Spanish, Italian and Portuguese, and Latin is also the primary language of some churches, such as the Roman Catholic Church. Note that English is not a "romance" language and is not directly descended from Latin; but English did borrow greatly from Old French, which is a romance language.

The Romans are not known for their intellectual achievements. They valued education only for its practical benefits, and Romans contributed less intellectually than the Greeks did. On a practical level the Romans accomplished much with their roads, orderly society, and system of justice. Roman law held together its vast empire just as Greek culture held together the Hellenistic world. Perhaps most of all, Christianity ultimately grew in the Roman empire.

The Roman Empire and Christianity[edit]

Jesus did not seek fame and many could not recognize Him; recall that the betrayal by Judas was needed to identify Jesus. But non-believing historians like Josephus (A.D. 37-100) recorded Jesus's life:

- "At this time there was a wise man who was called Jesus. ... Pilate condemned Him ... to die. And those who had become His disciples did not abandon His discipleship. They reported that He had appeared to them three days after His crucifixion and that He was alive; accordingly, He was perhaps the Messiah concerning whom the prophets have recounted wonders."[2]

and also:

- "Now, there was about this time, Jesus, a wise man, ... for he was a doer of wonderful works--a teacher of such men as receive the truth with pleasure. He drew ever to him both many of the Jews, and many Gentiles. ... [W]hen Pilate, at the suggestions of the principal men amongst us, had condemned him to be condemned and to the cross, those that loved him at the first did not forsake him, for he appeared to them alive again the third day, as the divine prophets had foretold these and the ten thousand other wonderful things concerning him; and the tribe of Christians, so named from him, are not extinct at this day."[3]

After the Resurrection, Peter and Paul brought Christianity to many parts of the Roman Empire, and Peter is recognized by the Roman Catholic Church ("catholic" is from a Greek word meaning "universal") as its first and longest-serving "bishop of Rome," or "pope" of the Church. The works of Peter, Paul and others in spreading Christianity are described in their own letters that follow the Gospels in the New Testament.

As Christianity grew, it began to organize itself along the lines of local parishes managed by priests, who in turn were selected by bishops. A group of local churches forms a diocese. Christianity is primarily an evangelical faith, and spreading its truths is considered a fundamental aspect of its doctrine. By seeking conversion of others to the Good News, Christianity differs from other religions that lack an evangelical component, such as Judaism. Popes were established in both Rome (a line of succession from Peter) and Alexandria, Egypt (a line of succession from Mark), and church law began to develop, known as "canon law."

While Christianity was and is primarily peaceful in its evangelism, Roman emperors were brutal in attempting to suppress the religion. Roman emperors Nero and Diocletian would actively persecute Christians, thereby creating many martyrs, but the religion continued to grow. Christians would hold worship services in secret places, making use of pre-existing catacombs or tunnels underlying Rome. There were numerous early Christian martyrs in Rome, such as Lawrence, who openly expressed their faith. In A.D. 258, the Roman emperor abruptly issued an edict that all bishops, priests and deacons be immediately killed ("episcopi et presbyteriet diacones incontinenti animadvertantur"). The bishop of Rome (the pope) was found in a catacomb and immediately executed. Lawrence, accordingly to verbal tradition, was roasted to death by a red-hot grid. A very inspirational martyr, Lawrence reportedly declared courageously during his execution, "Turn me over. I am done on this side!"

There were many other Christian martyrs, such as a Christian named "Valentine". In A.D. 269, the Roman Emperor Claudius II ("Claudius the Cruel") banned marriages because he was having difficulty raising an army. Valentine defied the order and performed Christian marriages in secret. Inevitably Valentine was discovered, and he was sentenced to be beaten to death with clubs and beheaded. The jailor's daughter visited him during his imprisonment and just before his death on February 14th, Valentine wrote her a sweet letter that he signed, "From your Valentine."

The inspiration by the Christian martyrs ultimately prevailed over the mighty Roman empire. Official persecution of Christians in the Roman empire ended with the Edict of Milan in A.D. 313, issued by the emperor Constantine. This edict established Christianity as an acceptable religion to be practiced in Rome. In A.D. 391, emperor Theodosius declared Christianity to be the official religion of the Roman empire and the worship of Roman gods was outlawed. The only legal religions in the Roman empire were then Christianity and Judaism. All the Roman emperors after Constantine were Christian, with one exception (Julian "the Apostate").

Constantine built a new Christian capital in the East for the Roman empire that would be safe from the German invaders, and he called it Constantinople. The city was located to benefit from the expanding trade with the East. He built the beautiful Church of Holy Wisdom there, now known as the "Cathedral of the Hagia Sophia." This city survived and thrived for another 1000 years, as the eastern portion of the Roman Empire did not decline and fall as the western portion did. The architecture of this city, now known as Istanbul, Turkey, is a mixture of Christianity and Hellenistic classicism. It is located on the Bosporus Strait at the point where Europe meets Asia, and was the wealthiest city in Europe throughout the Middle Ages. Half the city is in Europe and the other half is in Asia. It was sometimes called the "Queen of Cities."

Meanwhile, Christianity was hindered by heresies (false doctrines). The biggest heresy was "Arianism", based on teachings of a Libyan priest in Alexandria, Egypt, who declared that Jesus was an exceptional man but was not divine (God). To address this heresy, Constantine convened the Council of Nicaea, in A.D. 325 in Asia Minor (present-day Turkey), and he presided over it. This was the first of several important ecumenical councils held by Christians, as one was held every 50 or 100 years. The 300 Christian leaders declared that Jesus was a human who was also fully and eternally divine, and they excommunicated and banished Arian (i.e., the emperor Constantine forced him into exile). This issue did not generate as much of a division amongst the bishops as some modern authors suggest, and only two of over 300 bishops dissented when the nature of Jesus's divinity was voted upon.

The Christian leaders issued the Nicene Creed, which confirms the divine Trinity of God, Jesus and the Holy Spirit. Virtually all Christians of almost any denomination today, Protestant and Catholic, adhere to the Nicene Creed, and many Christians recite it daily or weekly. Arianism was simpler than Christianity and gained popularity for a while among Germanic invaders of the Roman Empire, but lost influence after the 8th century A.D.

Another Christian heresy was "Gnosticism", based on the Greek work for knowledge ("gnosis"). The Gnostics claimed to rely entirely on knowledge or reason, and later the word "agnostic" was coined to describe people who claim that recognition of God is impossible because it is somehow beyond human reasoning. There are implied criticisms of the Gnostics in the letters included in the New Testament (see, e.g., 1 Timothy 1:4), so this dispute goes back to the very early days of Christianity. The Gnostics promoted works as scriptures that were doubted or rejected by other Christians, such as the "Gospels" of Thomas and Judas. Gnostics would also edit out passages from accepted Gospels if they felt it could not be proven, such the reference in Luke to an angel coming to strengthen Jesus during his agony prior to the Crucifixion (Luke 22:43-44). Gnosticism had its roots in pre-Christian philosophy, and it persists to this day in attempts to pick and choose from the New Testament, and supplement it with Apocrypha (non-authentic works), as in the Da Vinci Code book and movie.

Jewish Rebellion and the Second Diaspora[edit]

The Roman Empire was brutal not only to the Christians but also to the Jews. Going back to A.D. 66, Jewish "Zealots" from Judea rebelled against the Romans and a bitter struggle followed. Titus's Roman army was far more powerful, however, and killed many of the Zealots and then senselessly destroyed the sacred temple in Jerusalem in A.D. 70, leaving only the Wailing Wall that remains to this day for Jewish believers to pray before. Then, in A.D. 73, Jewish holdouts in a fortress near Masada finally succumbed after years of courageous fighting against the more powerful Roman army. Herod the Great had built a fortified palace there in a rocky hill on the southwest shore of the Dead Sea, between 37 and 31 B.C. Herod built it for his own protection in case there were a Jewish revolt against him, but the Zealots later captured it for the purposes of their own revolt. After two years of a courageous defense against the Romans, the Romans finally prevailed with a battering ram in breaching the defenses. The oral tradition is that the Romans used Jewish slaves, whom the Zealots were reluctant to kill. Rather than submit to Roman authority, the Zealots killed each other (out of respect for the Jewish prohibition against suicide).

Another Jewish rebellion against the Romans occurred in A.D. 132, and this time the Romans completely destroyed the Jewish state and dispersed the Jewish people to faraway lands. This is known as the "Second Diaspora" ("diaspora" is Greek for dispersion). (The "First Diaspora" was the Babylonian captivity.) There would not be another Jewish homeland until 1948. After the Second Diaspora some Jewish people converted to Christianity, while others formed Jewish communities in faraway places. By A.D. 1000, Spain became a center for Jewish scholarship, but the Spanish Inquisition in A.D. 1492 is blamed for expelling Jews from that country. Eastern Europe welcomed displaced Jewish settlers, and by the 17th century it became the center of the Diaspora. In the late 1800s many Jewish people migrated to Germany and Britain, but the Holocaust in Germany during World War II destroyed Jewish communities there. The center of the Diaspora today is the United States, which has a Jewish population of nearly 6 million, more than the 5 million Jewish population of Israel, founded in 1948. Great Jewish centers such as Egypt and Babylon (now Iraq), which thrived in the first century, now have fewer than 1000 Jewish residents.

Augustine and Jerome[edit]

Towards the end of the Roman empire, in the early 5th century A.D., Augustine of Hippo (known to many as "Saint Augustine") wrote books entitled Confessions and City of God, which merged classical and Christian viewpoints, and in particular reconciled the classical (Greco-Roman) view about knowledge and virtue with Christian views of sin. Born in North Africa to a pagan father and a Christian mother, Augustine went through personal spiritual crises before converting to Christianity and advocating justification by grace alone. He criticized all the heresies of his time and supported the sacraments of the church. He also supported the concept of "predestination", which would later be emphasized by the Frenchman John Calvin during the Protestant Reformation in the 1530s (Calvin fled to Switzerland to promote his ideas).

A contemporary of Augustine was Jerome ("Saint Jerome"), who translated the Hebrew Old Testament and Greek New Testament into Latin. This became known as the Vulgate, and remained the authoritative Bible for more than 1000 years.

Enemies Causing Fall of the Roman Empire (in the West)[edit]

A barbaric, nomadic tribe known as the Asiatic Huns began moving into Europe from Asia in two independent tribes of nomadic barbarians, the Germanic Goths and Asiatic Huns. They launched fierce attacks on the Roman empire in the West in the late 300s (A.D.). The western Goths were known as "Visigoths".

In A.D. 375, the Huns invaded Europe from Asia. The Huns then settled in present-day Hungary. This forced the Goths to flee their homeland on the northern shore of the Black Sea. Specifically, the Huns displaced the Ostrogoths, who in turn displaced the Visigoths. The Visigoths initially requested and received permission from the Romans to cross the Danube River and settle in the Roman empire. But soon the Roman authorities began fighting with the Visigoths, and at the Battle of Adrianople in A.D. 378 the Visigoths defeated the Romans and killed the Roman Emperor Valens.

Meanwhile, other ethnic groups migrated around Europe in what is called the "Migration of the Peoples." Times were changing and the Roman empire was not likely to survive. In A.D. 410, the Visigoths, led by their king Alaric, invaded and "sacked" (ransacked) Rome.

Attila the Hun[edit]

The Huns had tremendous horsemanship skills that enabled them to strike with lightning speed. They were also extraordinarily accurate archers on horseback, and made ferocious charges on their enemies. The nomadic Huns defeated everything in their path from A.D. 370 to 455 in southeastern Europe, creating widespread panic throughout the Roman empire. The fear they inspired in their enemies was worse than anything in history.

Ultimately two brothers, Attila and Breda, rose to power in leading the Huns. Then Attila took power for himself by killing his brother!

Attila became King of the Huns from A.D. 434 to 453, and he was perhaps the most vicious and barbaric military leader in all of history. Known as "Attila the Hun," everyone was completely terrified of him and called him the "Scourge of God." One rumor was that Attila was a cannibal. He married seven women in his lifetime. The Huns were so barbaric that they did not use fire, and would simply eat raw or semi-raw meat that they found in dead animals. They were extremely fierce in battle. Superb horsemen, the Huns could shoot a bow accurately while riding a horse, benefiting from stirrups that their opponents did not have. The Huns would scream in battle and not follow any system of organized warfare, instead preferring complete chaos on the battlefield. They would fight to the death without any regard for their own safety. Defending against them was more difficult than, for example, fighting off hundreds of hornets after disturbing their nest.

Attila the Hun himself lived a simple life, wearing plain clothes consisting of layered animal skin. An envoy from the Eastern Roman empire who met with Attila once at dinner described it as follows:[4]

- By mixing up the languages of the Italians with those of the Huns and Goths, [an entertainer] fascinated everyone and made them break out into uncontrollable laughter, all that is except Attila. He remained impassive, without any change of expression, and neither by word or gesture did he seem to share in the merriment ....

The impression left was that Attila lacked a sense of humor and enjoyed only brutal warfare.

As a young warrior, Attila had been captured and released by the Romans, and he vowed to return to Rome victorious as king. Relying on seers and "gods", Attila nearly did conquer the Roman empire. For five years from A.D. 445 to 450 he devastated the eastern Roman empire, destroying anything in his path between the Rhine and the Caspian Sea. In 451 he amassed perhaps the largest army in the history of the world until that time, a total of a half-million men, and began marching towards Rome. He quickly conquered Gaul (present-day France) and devastated any European city in his path. He was not stopped until an alliance of the Visigoths and Romans surprised the Huns and forced them to retreat by about a hundred miles. One of the most bloody battles in all of history, the Battle of Chalons, ensued. The Visigoths and Romans defeated the Huns there.

But Attila was clever, and redirected his Huns towards Rome by invading Italy. He was headed towards the heart of the Roman empire: Rome itself. He destroyed everything in his path in the Roman countryside. Unable to stop Attila the Hun by force, a peaceful mission led by Pope Leo I traveled out to meet Attila in 452 and tried to persuade him to spare Rome. Moral persuasion worked where violence had not, and Attila did not invade Rome.

A year later, at only age 47, Attila died apparently from a mere nosebleed, choking to death on his own blood. It was an ironically pathetic cause of death for one of the most feared warriors in the history of the world.

Germanic Tribes[edit]

Attila was gone, but the Germanic tribes remained to wreak havoc on the Roman empire and ultimately ensure its complete fall. These Germanic tribes included the Saxons in northern Germany; the Angles and Saxons in England; the Visigoths in Spain; the Ostrogoths in Italy; the Vandals in North Africa; and the Franks in France.

The Germans to the north of the Roman empire began to show signs of their might that would resurface in the two world wars of the 20th century. In the ancient world the Germans had three dialects: Nordic (which later became Scandinavian languages), the western dialect (which later became modern German), and the eastern dialect (also known as Gothic).

To the Romans and Greeks, the Germans were an uncivilized people incapable of farming, as they lived in clans of 10-20 families, directed by tribal kings in war. They had no territorial allegiance, operating under fierce personal loyalty instead.

The German tribes would raid the Roman civilizations on the frontier along the Rhine, Danube and the north shore of the Black Sea, capturing women and slaves in the raids to send back to do domestic work. The Roman empire under Caesar was strong enough to repel these attacks, capturing the blond-haired invaders and turning them into slaves of Rome. But over time the Germans learned to organize themselves and the Roman empire on the frontier became less civilized: the line between civilization and barbarism became blurry. By the third century A.D., it was not always clear which side was the civilized one!

The Germanic nomads caused rural peasants to flee into the cities, weakening them. Recall that in A.D. 410 the Visigoths, a wandering nation of Germanic people from the northeast, led by King Alaric, sacked Rome itself. Another German chieftain named Odoacer finished the job off in A.D. 476, when he dethroned the last Roman Emperor of the West: Romulus Augustulus.

Persians[edit]

Another powerful enemy was poised to attack from east of the Roman empire. The Persians had been weakened by internal conflict until Ardashir, grandson of Sassan, killed the last Parthian king in 224. That heralded the beginning of the Sassanian dynasty, which ruled for hundreds of years until the Arabs arrived in 637-51.

The Sassanians pulled together their crown and the provinces, strengthened their cities and improved their organization. Ardashir then proceeded to take north Mesopotamia back from the Roman empire. His son Shapur I (A.D. 240-72) invaded as far west as Antioch and even took the Roman Emperor Valerian prisoner in A.D. 260. Shapur I took control of Afghanistan and Turkestan, and his son, Shapur II (A.D. 309-79), annexed them.

Shapur I improved the culture of Persia, commissioning translations of Greek and Indian works on philosophy, medicine and astronomy. He protected religious figures like Mani, who attempted to adapt Christian concepts to ancient Iranian principles of good and evil and thereby create a religion to suit the entire world at the time. A state church was created, but ultimately Mani was crucified and his followers, the Manicheans, were persecuted.

But the Persians had the same problems that plagued the Romans: raids by uncivilized peoples on their frontiers. The decline of the ancient world was not so much due to one civilized group defeating another, but rather the calamity of barbarians destroying civilization.

Other Reasons for Fall of the Roman Empire (in the West)[edit]

A.D. 476 is the date used for the "fall" of the Roman empire. That was when the last Roman Emperor, nine-year-old Romulus Augustus, was deposed (removed from power). Keep in mind, however, that the eastern half of the Roman empire based in Constantinople that split from the west in A.D. 264 never "fell"; it thrived for another thousand years.

There was not a single event that ended the ancient world, or even a series of events. But by A.D. 600, there was very little left of ancient civilizations, and all the intellectual and cultural progress had ceased. The culture, the military, the upkeep of roads, the sense of justice, and the governments were gone.

The Roman empire was the last of the great ancient civilizations, and countless papers, books and Ph.D. theses (dissertations) have been written trying to explain why the Roman empire collapsed. In the 1700s, British historian Edward Gibbon wrote a comprehensive six-volume set of books entitled The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.[5] This became the most celebrated work of English historical literature. Gibbon attributed the decline of the Roman empire primarily to the rise of Christianity. Roman citizens began to care more about heaven than earth, in Gibbon's view, and supposedly stopped caring so much about work and government. However, this argument may not persuade you, as nations with overwhelmingly Christian populations have thrived throughout history. Also, Gibbon's theory does not explain why the western half of the Roman empire fell but the eastern half did not. Both were Christian.

The military invasions by barbarians described above were an obvious factor in the fall of civilization. They were a constant distraction to the Roman emperors and ultimately the Roman army could not continue to fend off the attacks. The army itself was vulnerable to disloyalty, as it enlisted barbarians who cared little about Rome. Enormous political instability resulted in 28 different generals (the "barracks emperors") in less than 100 years.

Economists often say that all of history can be explained by economic trends, and the decline of the Roman empire is an example. Diocletian's economic policies were dreadful, imposing price controls and ordering people to stay in their current jobs. Emperors spent lavishly on themselves and other friends and the currency suffered from inflation that accompanies overspending by government. Like modern governments, the Roman emperors produced cheap coins when they needed money, thereby causing inflation. Economic problems resulted, and small farmers sold their family land to large estates. An early form of feudalism called "Patrocinium" developed whereby farmers worked on land owned by others. Eventually many farmers gave up and migrated to cities. But slave labor was popular in the cities, so the former farmers could not obtain jobs and large unemployment resulted. With nothing to do, crowds began to look for entertainment.

The aphorism "idle time is the work of the devil" applied to the people of Rome. For entertainment, people would go to the Colosseum and watch people (at one time, Christians) be fed to lions, or see two gladiators fight each other until one died. The morality of the Roman people was in complete decline. It was like everyone now spending hours each day watching murder on television, except it was real then. Nothing is achieved, and the content of the entertainment becomes increasingly immoral.

The imposition of heavy taxes also had a demoralizing effect. Failed harvests compounded the economic problem. Moreover, the reliance by the Roman economy on slavery eventually hurt the civilization, as the wealthy became accustomed to doing nothing and having free labor to work for them. Social decay accompanied the idle time and abusive use of free labor. The peaceful time known as Pax Romana has been blamed for not bringing in revenue from foreign wars, as Rome was no longer looting foreign territory. The end of the expansion of the Roman empire led to an end of the new revenue, and collapse from within. It appears that the economic model for success of the Roman empire required continual expansion to succeed. Illness did not help either: a plague reduced the population of Rome.

A lack of leadership contributed to the decline. Under the theory that leaders, not ideas, define history, the Roman empire can be described as thriving when it had strong leaders (emperors), and failing when it did not. Julius Caesar (100-44 B.C.) was a strong leader, and he is credited with establishing the Roman empire in the place of the Republic, which did not have a strong leader. During Pax Romana, there was a series of strong emperors. But upon the end of the Pax Romana in A.D. 180, the empire was handled by weak, incompetent or crazy emperors, many of whom served only a brief period before being assassinated. The end came with a nine-year-old emperor being removed from power by a foreign invader. That could hardly be a surprise to anyone.

Perhaps the Roman empire was too big and too diverse to maintain indefinitely. No other empire has been able to control that much territory, with all its diversity, for hundreds of years. Future leaders tried to restore the Roman empire; Charlemagne claimed in A.D. 800 that he had reestablished it. But the full power and glory of the Roman empire was gone forever.

The Byzantine Empire (in the East)[edit]

Recall that Constantine I ("Constantine the Great") became emperor of the western half of the Roman empire after his father died in battle.

Emperor Constantine promised that he would convert to Christianity (as his mother had) if God would make him victorious in the difficult battle in A.D. 306. Constantine won and then converted. In A.D. 312, Constantine began using Christian symbols for his military after seeing a vision of the sign of the cross in rays of sunlight. In 326, Constantine declared Sunday to be a religious holiday. By the time of his death in A.D. 333, Constantine had declared Christianity as an official religion of the Roman empire, and the Eastern Orthodox Church adores him as a saint to this day.

Establishing Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire is what made Constantine so important, but he was also brilliant in recognizing the significance of the eastern half of the Roman empire. That happened as follows. Constantine fought the ruler of the eastern half beginning in A.D. 314. In 323, Constantine ultimately conquered the East and killed its emperor, Licinius, thereby uniting West and East into one mighty Roman empire. Constantine founded a second capital in the East at Byzantium, renaming it Constantinople in his own honor (which is now Istanbul, Turkey).

The eastern half was always richer and stronger, and it survived as the Byzantine Empire through the Middle Ages. Constantine had placed his name on a city that would play an instrumental role in trade and military conflicts. The eastern half split from the west in A.D. 395 and grew in power and wealth, surviving for nearly a thousand years after the fall of Rome.

In A.D. 527, Justinian became a powerful emperor of this Byzantine empire. He recovered North Africa from the Vandals in 533 and Rome from the Ostrogoths in 535. Ultimately he recaptured all of Italy and even parts of Spain in his attempt to reestablish the Roman empire. Initially the primary language was Latin, as in Rome, but eventually Greek became the more important language in the eastern half.

Justinian is remembered best for revising and updating the Roman laws and establishing a new Justinian Code for laws and treaties. This was so successful that it was used for the next 900 years. He also rebuilt Constantinople, which had been destroyed by riots against high taxes. He rebuilt the fabulous Hagia Sophia church, which features the Byzantine architecture of high domes. His wife's name was Theodora, who was an advocate for more rights for women.

The Byzantine empire survived from Justinian's death in 565 all the way until 1453, when the Muslim Ottoman Turks conquered it in its weakened state. There are several causes of the decline prior to being conquered in 1453. A plague weakened the Byzantine empire in 700. In 1071, the Seljuk Turks defeated Byzantium at the Battle of Manzikert, and these Turks thereby acquired control of most of Asia Minor. Later Byzantium was weakened by an overly complex system of government; the term "Byzantine" today means unnecessarily complex rules of government.

References[edit]

- ↑ John 18:37-38 (NAS) (emphasis added)

- ↑ Antiquities, xviii.ch. 3, subtopic 3, Arabic text. http://www.bibleviews.com/non-biblical.html

- ↑ Antiquities, xviii.ch. 3, subtopic 3, Greek text. http://www.bibleviews.com/non-biblical.html

- ↑ Priscus. Dinner with Attila. Translated in Robinson, JH. Readings in European History (1905). Available at: http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/attila.htm

- ↑ http://www.ccel.org/ccel/gibbon/decline/files/decline.html

Categories: [World History lectures]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 03/07/2023 08:09:12 | 68 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/World_History_Lecture_Four | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF