Immigration

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia Immigration is the settlement of a foreigner in another nation. The reasons immigrants leave their homeland can vary, but it is often to benefit from entitlements or opportunities in the new country. Economic migration is more common in the 21st century, though immigrants also come in search of religious and politica freedom, and better educational opportunities. War, and other forms of violence, also causes people to leave their homeland. Strict national immigration policies can be effective at controlling immigration when enforced.[1] Approximately 10 million European immigrants came to the United States between 1865-1900, most in search of religious freedom and greater prosperity.

Contents

US Immigration history[edit]

Contrary to globalist and open borders talking points, the United States is not a "nation of immigrant",[2] but rather of descendants of immigrants. This talking point is often used as an argument in favor of mass levels of migration, including illegal immigration.[3] However, Europeans colonized America and imported African slaves to further increase the non-indigenous population..

Colonial America[edit]

Most of the migration to the thirteen colonies came from Britain, with English, Scots and (Protestant) Irish[Citation Needed] ancestry. The earliest of these are not technically considered "immigrants", because they were conquering a foreign land from its inhabitants for the British Empire.[4]

A large number of German immigrants came to Pennsylvania and New York. To this day they are called "Pennsylvania Dutch" but they were Germans, and came for religious freedom and economic opportunity. Dutch did come and settle in New Amsterdam (now New York), which was part of the Dutch Empire so they were not "immigrants" either. Black slaves were involuntary immigrants to all the colonies, especially the tobacco plantations of Virginia and Maryland, and the rice plantations of South Carolina. The American Revolution cut off movement from 1775 to 1783. When it resumed, about 80,000 American Loyalists left the U.S. to immigrate to Canada or return to Britain. Migration was light before 1815, because of wars in Europe. The import or export of slaves was made illegal in 1809.

Early Nation: 1776–1860[edit]

At the Constitutional Convention, Founder Gouverneur Morris declared that anybody who would refer to themselves as a "citizen of the world" is the kind of person that he would not trust, and he went on to say that "every Society from a great nation down to a club had the right of declaring the conditions on which new members should be admitted".[5][6]

Historians have shown that in the nineteenth century, the U.S. was a place where immigrants could stake their claims for a new life. After arrival, German and Irish immigrants settled regionally by nativity within the U.S. The Irish accounted for 68% of all immigrants to the Northeast; Germans accounted for 47% of all immigrants to the Midwest; British immigrants accounted for 19% of immigrants to the Northeast and 20% of immigrants to the Midwest. After arrival, the British, German, and Irish achieved success in U.S. labor markets, and the British and German immigrants found opportunity in skilled occupations. Irish Catholic immigrants did not fare as well as the other two groups in terms of jobs and economic status, but still fared better than had they remained in Ireland. Moreover, all groups sharply improved their average skills in the U.S. after arrival. Wages were much higher in the U.S. than in Europe, and it was much easier to own a farm. However, Americans worked much harder than their European cousins and took fewer holidays.

Cohn (2009) asks, "Did immigration help or hurt native labor and did migration lead to long run economic growth?" Immigration increased the long-run rate of economic growth. During the nineteenth century, immigration extended the U.S. product market and allowed labor in manufacturing and agriculture to specialize. Larger pools of unskilled labor after 1845 put downward pressure on wages. However, over time, labor markets adjusted, migrants assimilated, and the economy moved forward.

Gilded Age: 1860–1900[edit]

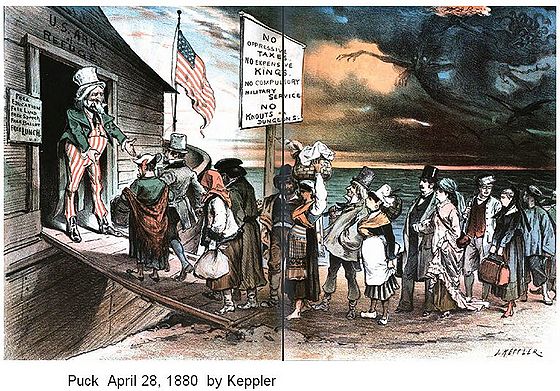

During the Gilded Age, 1865-1900, approximately 10 million European immigrants came to the United States, most in search of religious freedom and greater prosperity. They filled up the rich farmlands of the Middle West, as German and Scandinavian immigrants were especially eager to own land. They avoided the poverty-stricken South. The population surge in major U.S. cities as a result of immigration gave cities an even stronger impact on government, attracting power-hungry politicians and entrepreneurs. Pressuring voters or falsifying ballots was commonplace for politicians, who often sought power only to exploit their constituents. To accommodate the influx of people into the U.S., the federal government built Ellis Island in 1892 near the Statue of Liberty. After 1892, a short physical examination was given; those with contagious diseases were not admitted. Few immigrants went to the poverty-stricken South.

"During the mass emigration from Italy during the century between 1876 to 1976, the U.S. was the largest single recipient of Italian immigrants in the world... In 1850, less than 4,000 Italians were reportedly in the U.S. However in 1880, merely four years after the influx of Italian immigrants migrated, the population skyrocketed to 44,000, and by 1900, 484,027." [7]

Chinese immigrants[edit]

The construction of the Central Pacific Railroad in California and Nevada was handled largely by American engineers and Chinese laborers. In the 1870 census, there were 58,000 Chinese men and 4,000 women in the entire country; these numbers grew to 100,000 men and 4,000 women in the 1880 census.[8] Labor unions such as the American Federation of Labor strongly opposed the presence of Chinese labor, by reason of both economic competition and race. Immigrants from China were not allowed to become citizens until 1950; however, their children born in the U.S. were full citizens.

Congress banned further Chinese immigration through the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882; act prohibited Chinese laborers from entering the United States, but some students and businessmen were allowed in. Subsequent to the act, the Chinese population declined to only 37,000 in 1940. Many returned to China (a greater proportion than most other immigrant groups) yet most of them stayed in the United States. Chinese people were unwelcome in many areas, so they resettled in the "Chinatown" districts of large cities.

Later history[edit]

After seeing a high level of immigration, the U.S. government took measures such as the Immigration Act of 1924 to reduce the number of migrants, a period which lasted from about 1925 to 1966.[9] After the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 was enacted, immigration levels reached new highs, and in 2017, the number of foreigners in the U.S. reached the highest level since 1910.[10]

US immigration reform[edit]

Most Americans envisage and advocate for a coherent set of national interest principles for immigration policy and the enforcement our Constitutionally derived laws. Many open borders advocates try to cloak themselves in the mantle of "immigration reform," a liberal euphemism, but they fail to address the concerns of the American populace and detriments to foreign countries that lose people. Due to lack of enforcement, illegal immigration occurs widely in the U.S., especially along the Mexican border.

To some people, the value of American citizenship has increased greatly since the founding of the Republic. There are 12 million illegal immigrants in the United States and it would be very costly to deport all these people. It becomes more complicated as they marry and have children which are then legal US citizens. There is a discussion of allowing these 12 million people to follow certain steps to become citizens that can pay taxes and become more contributing members of society. Some people view this as granting amnesty to criminals but do not offer an actual solution to the immigration problem.

While Congress considers new laws, the federal government is left with the task of enforcing existing laws fairly. For example, on November 14, 2016, the US Department of Justice filed a suit against two Washington State-based potato processing companies for discriminating against immigrant workers. These companies had allowed citizens flexibility in proving their status, but had unfairly limited immigrants in to prove their work authorization.[11]

A Harvard/Harris Poll conducted in the Summer of 2019 revealed that 69 percent of swing voters said they are somewhat unlikely or very unlikely to support a 2020 presidential candidate that supports opening the U.S.-Mexico border to more illegal and legal immigration. Overall, about 64 percent of registered voters said they would be more unlikely to support a 2020 presidential candidate that backs increasing illegal and legal immigration to the country — including about 63 percent of Generation X voters, 45 percent of Democrats, and 66 percent of voters who describe themselves as “moderate.”[12]

Immigration to Australia[edit]

Immigration has been prominent in Australia's history since the beginning of British settlement in 1788. Originally used as a location for convicts, the discovery of gold in Victoria convinced other British people to come to Australia. For generations, most settlers came from the British Isles, and the people of Australia are still predominantly of British or Irish origin, with a culture and outlook similar to those of Americans. A "White Australia" policy operated from 1901 to the 1960s; it encouraged immigration by Europeans and blocked almost all other immigration.

Immigration to Europe[edit]

Religion and migration[edit]

See also[edit]

- Chinese Exclusion Act

- German Americans

- Illegal immigration

- Chain migration

- Latinos

- Refugee

- Swedish Americans

- Racism

- 287(g)

Bibliography[edit]

Basic further reading[edit]

- Archdeacon, Thomas J. Becoming American: An Ethnic History (1984), by leading conservative historian

- Barkan, Elliott Robert. And Still They Come: Immigrants and American Society, 1920 to the 1990s (1996), by leading historian

- Barkan, Elliott Robert, ed. A Nation of Peoples: A Sourcebook on America's Multicultural Heritage (1999), 600pp; essays by scholars on 27 groups

- Barone, Michael. The New Americans: How the Melting Pot Can Work Again (2006), by a conservative expert excerpts and text search

- Bodnar, John. The Transplanted: A History of Immigrants in Urban America (1985), liberal historian

- Daniels, Roger. Coming to America 2nd ed. (2005), liberal historian

- Dassanowsky, Robert, and Jeffrey Lehman, eds. Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America (2nd ed. 3 vol 2000), home school audience; covers 150 culture groups; 1974pp

- Gjerde, Jon, ed. Major Problems in American Immigration and Ethnic History (1998) primary sources and excerpts from scholars.

- Glazier, Michael, ed. The Encyclopedia of the Irish in America (1999), articles by over 200 experts, covering both Catholics and Protestants.

- Levinson, David and Melvin Ember, eds. American Immigrant Cultures 2 vol (1997) covers all major and minor groups

- Meier, Matt S. and Gutierrez, Margo, eds. The Mexican American Experience: An Encyclopedia (2003) (ISBN 0-313-31643-0)

- Magocsi, Paul Robert. Encyclopedia of Canada's Peoples (1999), 1350 pp; major compilation

- Thernstrom, Stephan, ed. Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups (1980) (ISBN 0-674-37512-2), the standard reference, covering all major groups and most minor groups; Thernstrom is a leading conservative historian excerpt and text search

- Wittke, Carl. We Who Built America: The Saga of the Immigrant (1939), 552pp good older history cover major groups online edition

Recent migrations[edit]

- Adler, Leonore Loeb , and Uwe P.Gielen, eds. Migration: Immigration and Emigration in International Perspective. 2003 online edition

- Borjas, George J. "Does Immigration Grease the Wheels of the Labor Market?" Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2001 online edition

- Castles, Stephen, and Mark J. Miller. The Age of Migration, Third Edition: International Population Movements in the Modern World (2003)

- Glazier, Ira A. and Luigi De Rosa. Migration across Time and Nations: Population Mobility in Historical Contexts 1986 online edition

- Hernández, Kelly Lytle. “The Crimes and Consequences of Illegal Immigration: A Cross-Border Examination of Operation Wetback, 1943 to 1954,” Western Historical Quarterly, 37 (Winter 2006), 421–44.

- Kemp, Paul. Goodbye Canada? (2003), from Canada to U.S.

- Khadria, Binod. The Migration of Knowledge Workers: Second-Generation Effects of India's Brain Drain, (2000)

- Massey, Douglas S. and J. Edward Taylor; International Migration: Prospects and Policies in a Global Market, (2003) online edition

- Mullan, Fitzhugh. "The Metrics of the Physician Brain Drain." New England Journal of Medicine, Volume 353:1810-1818 October 27, 2005 Number 17 online version

- Ozden, Caglar, and Maurice Schiff. International Migration, Remittances, and Brain Drain. (2005)

- Palmer, Ransford W. In Search of a Better Life: Perspectives on Migration from the Caribbean Praeger Publishers, 1990 online edition

- Skeldon, Ronald, and Wang Gungwu; Reluctant Exiles? Migration from Hong Kong and the New Overseas Chinese 1994 online edition

- Smith, Michael Peter, and Adrian Favell. The Human Face of Global Mobility: International Highly Skilled Migration in Europe, North America and the Asia-Pacific, (2006)

Historical studies: world[edit]

- Baines, D. Migration in a Mature Economy: Emigration and Internal Migration in England and Wales 1861–1900, (1985),

- Clark, P. and D. Souden. Migration and Society in Early Modern England (1987),

- Eltis, David, ed. Coerced and Free Migration: Global Perspectives 2002 online edition 447pp

- Gungwu, Wang, ed. Global History and Migrations 1997 online edition 309pp

- Langton, J. and G. Hoppe. Flows of Labour in the Early Phase of Capitalist Development: The Time Geography of Longitudinal Migration Paths in Nineteenth Century Sweden (1992),

- Lawton, R. "Mobility and Nineteenth Century British Cities", The Geographical Journal, 145, (1979) 206–24.

- Luconi, Stefano. “Italians’ Global Migration: A Diaspora?,” Studi Emigrazione/Migration Studies (Rome), 43 (March 2006), 467–82. In English.

- Siddle, David J. ed Migration, Mobility, and Modernization 2000 online edition scholarly articles on European history

- Tilly, Charles. "Migration in Modern European History", in Time, Space and Man: Essays on Micro-Demography, Stockholm. (1979)

- Wrigley, G. A. (1967), ‘The Simple Model of London's Importance in Changing English Society and Economy 1650–1750’, past and Present, 37, 44–70.

Historical Studies: North America[edit]

- Archdeacon, Thomas J. Becoming American: An Ethnic History (1984)

- Bankston, Carl L. III and Danielle Antoinette Hidalgo, eds. Immigration in U.S. History (2006)

- Bodnar, John. The Transplanted: A History of Immigrants in Urban America (1985)

- Canada, Report of the Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration. (1885) primary documents for Canada (with reports on Chinatowns in U.S.) online edition

- Cohn, Raymond L. Mass Migration under Sail: European Immigration to the Antebellum United States (2009) 254 pp.; emphasis on economic issues

- Daniels, Roger. Coming to America 2nd ed. (2005)

- Daniels, Roger. Guarding the Golden Door : American Immigration Policy and Immigrants since 1882 (2005)

- Eltis, David; Coerced and Free Migration: Global Perspectives (2002) emphasis on migration to Americas before 1800

- Gjerde, Jon, ed. Major Problems in American Immigration and Ethnic History (1998) primary sources and excerpts from scholars.

- Glazier, Michael, ed. The Encyclopedia of the Irish in America (1999), articles by over 200 experts, covering both Catholics and Protestants.

- Green, Alan G. and Gree David. "The Goals of Canada's Immigration Policy: A Historical Perspective" Canadian Journal of Urban Research, Vol. 13, 2004 online version

- Hoerder, Dirk and Horst Rössler, eds. Distant Magnets: Expectations and Realities in the Immigrant Experience, 1840-1930 1993 online edition 312pp

- Hourwich, Isaac. Immigration and Labor: The Economic Aspects of European Immigration to the United States (1912) full text online, argues immigrants were beneficial to natives by pushing them upward

- Jenks, Jeremiah W. and W. Jett Lauck, The Immigrant Problem (1912; 6th ed. 1926) online edition of Jenkc and Lauck based on 1911 Immigration Commission report, with additional data

- Kulikoff, Allan; From British Peasants to Colonial American Farmers (2000), details on colonial immigration

- LeMay, Michael, and Elliott Robert Barkan. U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Laws and Issues: A Documentary History (1999) 340 pgs. online edition

- Miller, Kerby M. Emigrants and Exiles (1985), influential scholarly interpretation of Irish immigration

- Motomura, Hiroshi. Americans in Waiting: The Lost Story of Immigration and Citizenship in the United States (2006), legal history

- Thernstrom, Stephan, ed. Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups (1980) (ISBN 0-674-37512-2), the standard reference, covering all major groups and most minor groups

- U.S. Immigration Commission, Abstracts of Reports, 2 vols. (1911); the full 42-volume report is summarized (with additional information) in vol 1-2; see also Jencks and Lauck

- Reports of the Immigration Commission: Statements (1911) text of statements pro and con online edition

- Part 8: Leather Industry (1911) online edition

- Wittke, Carl. We Who Built America: The Saga of the Immigrant (1939), covers all major groups online edition

- Yans-McLaughlin, Virginia ed. Immigration Reconsidered: History, Sociology, and Politics (1990)

Recent immigration to North America[edit]

- Borjas, George J. ed. Issues in the Economics of Immigration (National Bureau of Economic Research Conference Report) (2000) 9 statistical essays by scholars;

- Borjas, George J. "Welfare Reform and Immigrant Participation in Welfare Programs" International Migration Review 2002 36(4): 1093-1123. ISSN 0197-9183; finds very steep decline of immigrant welfare participation in California.

- Briggs, Vernon M., Jr. Immigration Policy and the America Labor Force Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984.

- Briggs, Vernon M., Jr. Mass Immigration and the National Interest (1992)

- Fawcett, James T., and Benjamin V. Carino. Pacific Bridges: The New Immigration from Asia and the Pacific Islands . New York: Center for Migration Studies, 1987.

- Foner, Nancy. In A New Land: A Comparative View Of Immigration (2005)

- Levinson, David and Melvin Ember, eds. American Immigrant Cultures 2 vol (1997) covers all major and minor groups

- Meier, Matt S. and Gutierrez, Margo, eds. The Mexican American Experience: An Encyclopedia (2003) (ISBN 0-313-31643-0)

- Portes, Alejandro, and Robert L. Bach. Latin Journey: Cuban and Mexican Immigrants in the United States. University of California Press, 1985.

- Portes, Alejandro, and Jozsef Borocz. "Contemporary Immigration: Theoretical Perspectives on Its Determinants and Modes of Incorporation." International Migration Review 23 (1989): 606-30.

- Portes, Alejandro, and Ruben Rumbaut. Immigrant America. University of California Press, 1990.

- Reimers, David. Still the Golden Door: The Third World Comes to America Columbia University Press, (1985).

- Smith, James P, and Barry Edmonston, eds. The Immigration Debate: Studies on the Economic, Demographic, and Fiscal Effects of Immigration (1998), online version

Current data[edit]

- Arthur Haupt and Thomas T. Kane. Population Handbook, (Population Reference Bureau: 5th ed 2004) online edition

Advanced theoretical models[edit]

- Grigg, D. "E. G. Ravenstein and the Laws of Migration" Journal of Historical Geography, vol 3, (1977), 41–54.

- Lee, E. S. (1966), ‘A Theory of Migration’, Demography, 3, 47–54.

- Massey, Douglas S. "Theories of international migration: A review and appraisal." Population and Development Review, (1994). 19, 431-466. in JSTOR

- Ravenstein, E. G. "The Laws of Migration", Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, vol 48 (1885) pp 167–227.

- Ravenstein, E. G. "The Laws of Migration", Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, vol 52 (1889) pp 214–301. online at JSTOR

- Stouffer, S. A. ‘Intervening Opportunities: a Theory Relating Mobility and Distance’, American Sociological Review, (1940) vol 5, 845–67.

- Wolpert, J. (1965), ‘Behavioural Aspects of the Decision to Migrate’, Papers of the Regional Science Association, 15, 159–73.

- Zelinsky, Wilbur. "The Hypothesis of the Mobility Transition", Geographical Review, 61, (1971) 219–49.

See also[edit]

External links[edit]

- History of Immigration From the 1850s to the Present

- Issues of Illegal Immigration

- The Chinese

- The Jewish

- Then, from Egypt to Israel: Now, from Russia and the U.S.

References[edit]

- ↑ Helbling, Marc; Leblang, David (April 27, 2018). Controlling immigration? How regulations affect migration flows. European Journal of Political Research, 58: 248-269. doi:10.1111/1475-6765.12279.

- ↑ Multiple references:

- https://www.brookings.edu/product/our-nation-of-immigrants/

- Gonzalez, Pedro (July 8, 2018). America Is Not a Nation of Immigrants. American Greatness. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- Sutherland, Howard (November 18, 2002). The Nation of Immigrants Myth. The American Conservative. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- Binder, John (November 11, 2017). Steve Bannon: ‘We’re a Nation of Citizens; We’re Not a Nation of Immigrants’. Breitbart News. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- ↑ Munro, Neil (January 19, 2019). WATCH: New York Times Writer Explains Why a ‘Nation of Immigrants’ Needs Open Borders. Breitbart News. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- ↑ https://twitter.com/MarkSKrikorian/status/1123187983358808064

- ↑ Immigration and the American Founding, Hillsdale College

- ↑ Wrong On The Founders, National Review

- ↑ The Italians

- ↑ Historical Census Statistics on the Foreign-born Population of the United States: 1850-1990

- ↑ Binder, John (September 14, 2018). Immigration Moratorium Followed Last Period of Record U.S. Foreign-Born Population Levels. Breitbart News. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ Munro, Neil (September 14, 2018). U.S. Immigrant Numbers Hit 44.5 Million, Near 108-Year Record. Breitbart News. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ↑ Justice Department Files Lawsuit Against Washington Potato Company and Pasco Processing Alleging Discrimination Against Immigrants (Nov. 14, 2016). Retrieved on Aug 20,2017.

- ↑ https://www.breitbart.com/politics/2019/08/05/poll-swing-voters-hugely-oppose-2020-democrats-promising-more-immigration/

Categories: [Immigration] [United States History] [Gilded Age] [Globalism]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 03/05/2023 22:45:09 | 245 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Immigration | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:.PNG)

KSF

KSF