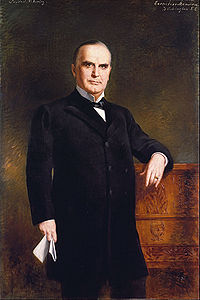

William Mckinley

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia | William McKinley | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| 25th President of the United States From: March 4, 1897 - September 14, 1901[1] | |||

| Vice President | Garret Hobart (1897–1899) Theodore Roosevelt (1901) | ||

| Predecessor | Grover Cleveland | ||

| Successor | Theodore Roosevelt | ||

| 39th Governor of Ohio From: January 11, 1892 – January 13, 1896 | |||

| Lieutenant | Andrew Harris | ||

| Predecessor | James Campbell | ||

| Successor | Asa Bushnell | ||

| Information | |||

| Party | Republican | ||

| Spouse(s) | Ida Saxton McKinley | ||

| Religion | Methodist | ||

| Military Service | |||

| Service/branch | United States Army Union Army | ||

| Service Years | 1861–1865 | ||

| Rank | Brevet major | ||

| Commands | Europe | ||

| Battles/wars | American Civil War | ||

William McKinley, Jr.[2] was the 25th President of the United States of America, serving from 1897 until 1901 as a Republican. In Congress he was a foremost advocate of high tariffs on imported goods that would encourage industry and protect high wages from cheap competition. Defeated after his McKinley Tariff passed in 1890, McKinley bounced back to win election as governor of Ohio in 1891 and 1893. A tireless speaker, he was the most popular man in the party; his campaign manager Mark Hanna helped assure his capture of the GOP presidential nomination in 1896, in the midst of a deep depression people blamed on incumbent Democrat Grover Cleveland. But Cleveland and his conservative, pro-business Bourbon Democrats were overthrown and the Democrats nominated firebrand William Jennings Bryan, who picked up Populist support and crusaded against banks, railroads, and the moneyed East, promising that Free Silver would pump money into the economy and destroy the wicked. McKinley and Hanna fought back, inventing new techniques in the most heated election campaign in American history. McKinley promised that high tariffs would benefit all Americans—and he introduced the goal of a pluralistic America whereby all Americans of whatever race or ethnicity would share in prosperity. He attacked free silver as dishonesty, and by speaking to hundreds of thousands of voters and organizing massive parades in every town and city in the North, McKinley and Hanna demonstrated they represented the American majority. McKinley won in a landslide, carrying the entire East and Midwest and parts of the West. He won huge majorities in most cities, and switched the large German American vote to the GOP, along with most factory and railroad workers, then middle classes, and the more prosperous farmers. The election of 1896 realigned American politics, as 1896 was a critical election marking the dividing line between the Third Party System of the Civil War and Gilded Age, and the Fourth Party System, usually called the Progressive Era.

As president McKinley rammed through higher tariffs and the gold standard, and watched prosperity return. Foreign affairs unexpectedly took center stage as Americans recoiled at the atrocities Spain committed to hold onto its colony of Cuba. McKinley tried to avoid war but public opinion—especially from the Bryanites—demanded it. The result was a "splendid little war," marked by sudden, overwhelming American victories on land and sea, with a few embarrassing bureaucratic mishaps in the War Department. Spain quickly gave up and turned over its main colonies, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines. Congress started the war promising Cuba its independence. McKinley decided to keep Guam and Puerto Rico, along with independent Hawaii which voluntarily joined the U.S. After long hesitation McKinley decided also to keep the Philippines. This made imperialism (along with free silver again) a central issue of the 1900 election. McKinley beat Bryan in a second landslide. Six months into his second term McKinley was assassinated by an anarchist and Theodore Roosevelt became president. McKinley is considered the first modern president for introducing modern campaign methods, for reorganizing the White House staff system, and for making the activities of the President the main ingredient in political news.

Contents

Early life[edit]

McKinley was born at Niles, Ohio, on Jan. 29, 1843, seventh of the nine children of William and Nancy Allison McKinley. The McKinleys, of Scotch-Irish descent, had moved to Pennsylvania in the early 18th century and became interested in the iron foundry business, which William's father later built in Ohio. In 1852 the family moved to the small town of Poland, Ohio, where William attended a local school. He entered Allegheny College at Meadville, Pennsylvania, in 1860, but left because of poor health and subsequently taught school. At the outbreak of the American Civil War, McKinley, then age 18, enlisted as a private in the Twenty-third Ohio Volunteer Infantry, commanded by Rutherford B. Hayes. He saw service in western Virginia and at the Battle of Antietam, after which he was commissioned a second lieutenant. He was mustered out of the army in 1865 as a major. He studied law in an office for a year and for a longer period at the Albany (N.Y.) Law School. Admitted to the Ohio bar in 1867, he opened an office in Canton, where he established a permanent residence. In 1871 he married Ida Saxton, the daughter of an influential local banker. After the birth of two daughters, Mrs. McKinley became an invalid for the rest of her life, her illness lightened only by the complete devotion of her husband.

McKinley entered politics early, greatly aided by his commanding presence, his oratorical ability, his sunny nature, and his willingness to negotiate and compromise. In 1869 he was elected prosecuting attorney of Stark County, and seven years later he helped nominate and elect his old commander, Rutherford B. Hayes, as President.

Congress[edit]

In 1876 McKinley was elected to Congress and was later re-elected twice, serving from 1877 to 1883. In 1882 he claimed election and took his seat in March 1883, but the seat was contested; McKinley held the seat and voted until the last day of the session, when it was given to his opponent by the Democratic majority, who delayed so long because they wanted to work with McKinley. He regained his seat in the election of 1884 and served until he was defeated in the election of 1890.

McKinley established himself as a spokesman for the nation's dominant industrial group, desiring highly protective tariff rates. This position, together with his ardent support of John Sherman for President in 1888, won him the friendship of Mark Hanna, an influential Cleveland industrialist who was a key Sherman supporter. It also assured him a place on the powerful Ways and Means Committee of the House, which wrote tax and tariff laws. As a high-tariff man he was twice made chairman of the committee on resolutions in the national conventions of the Republican Party. In 1889 he was selected as chairman of the Ways and Means Committee and in that position he became chief architect of the extremely high tariff act of 1890 bearing his name. To obtain western votes for the bill, he supported the Sherman Silver Purchase Act. He was chiefly responsible for defeating James G. Blaine's reciprocity amendments.

The public reaction to the McKinley tariff defeated his party and McKinley himself in the elections of 1890; but with the help of Hanna, the unquestioned boss of the Republican Party in Ohio, he was elected governor of the state in the following year and reelected in the depression year of 1893.

Presidential campaign of 1896[edit]

Hanna had been attempting for years to install John Sherman in the presidency. Turning his support to McKinley, he carefully guided his candidate through the next few years. Both McKinley and Hanna had planned to fight the campaign of 1896 on the tariff issue, but the pressure of the silverites in the Mountain states, the Populist Party on the Plains, and especially the agrarian forces led by William Jennings Bryan in the Midwest and South, made free silver and reform the critical questions. Here McKinley's record in voting for the Bland-Allison Act and the Sherman Silver Purchase Act was distinctly a liability for a big-business candidate. Hanna surmounted that troublesome question by private assurances and public equivocation. By combining the support of the business element with that of delegates from the South, he secured McKinley's nomination at the St. Louis convention and at the same time wrote the word "gold" into the Republican platform.

McKinley promised a return of prosperity, and assured every economic, social ethnic and racial group that it would share in the new prosperity. The latter was the first statement of pluralism in American politics.

McKinley was dubbed the "advance agent of prosperity" promising jobs for all Americans once the nation had a high tariff and the gold standard.

In the extremely hard-fought campaign McKinley, unlike his opponent, Bryan, made no speaking tours; instead, he met hundreds of visiting delegations on his front porch, speaking to some 550,000 voters (compared to the three million people who heard Bryan, many of whom were women and children.). Supported by Hanna's organization, he was victorious in November by an electoral vote of 271 to 176, and won more than 7,000,000 popular votes out of almost 14,000,000 cast.

President[edit]

McKinley was a cautious, conciliatory politician rather than a leader. Except for the tariff and Republican Party ideology, it is unlikely that he held any deep political convictions. In office, his aim was to continue to represent the industrial class which had supported him for so long in Congress, to maintain party solidarity, and to keep the United States at peace. He appointed Senator Sherman as Secretary of State in 1897 in order to provide a Senate seat for Hanna. The rest of his Cabinet was without distinction.

Immediately after taking office McKinley called a special session of Congress to revise the tariff. The session resulted in the passing of the Dingley Act, establishing the highest tariff rates in the history of the country. During the same year, 1897, he also submitted a treaty to Congress providing for the annexation of the Hawaiian Islands. Congress refused to ratify the treaty, but the territory was later annexed by the Resolution of 1898. Near the end of McKinley's first administration, a gold-standard act was passed, and this probably completed McKinley's program as he had conceived it in 1896.

Foreign policy[edit]

By far the gravest issue during McKinley's presidency concerned relations with Spain. For some years interested Americans in and out of Congress had demanded American intervention in Cuba with an eye toward seizing the island and other Spanish territory. Apparently McKinley had no objection to the creation of an American empire, but he was personally opposed to a war to obtain one. Unlike President Cleveland, however, he responded to pressure and intervened in Cuban affairs. After the insulting De Lome letter and the destruction of the U.S.S. Maine in Havana harbor in February, 1898, McKinley sent an ultimatum to the Spanish government demanding the abandonment of the Reconcentrado policy in Cuba and the institution of an armistice. After some delay Spain promised to meet most of the demands. McKinley, however, had already succumbed to the pressure for war and had written a message virtually asking for hostilities. Ignoring the Spanish answer, he submitted the message to Congress with the statement that he had "exhausted every effort to relieve the intolerable condition of affairs" in Cuba. Congress quickly declared war and this culminated in an easy victory over Spain, though woefully bad administration discredited both the War and Navy departments. By the treaty of peace, Spain evacuated Cuba and ceded Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippine Islands to the United States.

On the vexing question of whether this nation should take the Philippines and thus become involved in Asiatic power politics, McKinley apparently had no strong convictions. He waited for a considerable time and then decided in favor of the acquisition.[3] During the rest of his first term he busied himself with the reorganization of the War and Navy departments, with an effort to win the Open Door in China, and with the problems growing out of the newly acquired territory.

Reelection and Second Term[edit]

Enthusiastically renominated in 1900, McKinley refused to accept Bryan's challenge to fight the election solely over the issue of imperialism. Instead, he and his party supporters, pointing to the great prosperity of the country and using the slogan of the "full dinner pail," asked for re-election on the ground that a Republican victory would ensure the continuance of good times. He was re-elected with 292 votes in the electoral college against 155 for Bryan, and by a popular plurality of 900,000.

Death[edit]

Six months after his second inauguration he visited the Pan-American Exposition at Buffalo, N.Y. There, on Sept. 5, 1901, he first questioned his high-tariff doctrines by advocating a world reduction in customs rates by means of reciprocal treaties. He was not to live, however, to see his proposal adopted.

He was shot by an anarchist, Leon Frank Czolgosz, in Buffalo, New York on September 6, 1901. McKinley had received a number of death threats, and despite the objections of his advisors, insisted on meeting the public on this trip to Buffalo.[4] He died eight days later, and his Vice President, Theodore Roosevelt, became President. The nation mourned McKinley and Roosevelt promised to continue his highly popular policies.

Legacy[edit]

A memorial to McKinley was built in his hometown of Canton Ohio. It was funded by a grassroots fundraising campaign shortly after his death. Theodore Roosevelt gave the dedication speech. The monument features a domed building on a hill in which McKinley's body rests. There is a statue of him on the hill. Near the monument is a science and history museum. His home in Canton is now the National First Ladies' Historic Sight.

McKinley appears on the now out of print $500 bill. From 1898 until 2015, the Denali was named in his honor Mount McKinley.

See also[edit]

Bibliography[edit]

- Dobson, John M. Reticient Expansionism: The Foreign Policy of William McKinley. (1988).

- Faulkner, Harold U. Politics, Reform, and Expansion, 1890-1900 (1959). standard scholarly survey online edition

- Glad, Paul W. McKinley, Bryan, and the People (1964). short history of 1896 election

- Gould, Lewis L. The Presidency of William McKinley. (1981) the standard scholarly history

- Jensen, Richard. The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict, 1888-1896 (1971) a conservative perspective

- Jones, Stanley L. The Presidential Election of 1896. the standard history.

- Josephson, Matthew. The Politicos: 1865-1896 (1938) a leftist perspective

- Leech, Margaret. In the Days of McKinley. 1959, well-written popular history

- Morgan, H. Wayne. William McKinley and His America. 1963. biography by scholar

- Morgan, H. Wayne. From Hayes to McKinley: National Party Politics, 1877-1896 (1969), online edition

- Offner, John L. An Unwanted War: The Diplomacy of the United States and Spain over Cuba, 1895-1898 (1992) [ online edition]

- Olcott, Charles S. The Life of William McKinley. 1916, popular biography, online at Google

- Rhodes, James Ford. The McKinley and Roosevelt Administrations, 1897-1909 (1922), early scholarly history; Rhodes (a Democrat) was Hanna's brother-in-law

- Trask, David. The War with Spain in 1898. 1981.

- Williams, R. Hal. Years of Decision: American Politics in the 1890s (1993) survey by scholar

Primary Sources[edit]

- McKinley, William.Speeches and Addresses of William McKinley from March 1, 1897 to May 30, 1900. 1900. online at Google

- McKinley, William. Speeches and Addresses of William McKinley from his Election to Congress to the Present Time (1893) online at Google

- McKinley, William.The Tariff; a Review of the Tariff Legislation of the United States from 1812 to 1896 (1896) online at Google

References[edit]

- ↑ http://www.trivia-library.com/a/25th-us-president-william-mckinley.htm

- ↑ http://bioguide.congress.gov/biosearch/biosearch1.asp

- ↑ The story that he listened to God on the matter is probably apocryphal, but he did pray a great deal.

- ↑ Larry Schweikart and Michael Allen, "A Patriot's History of the United States" (Sentinel 2007)

External links[edit]

| |||||

Categories: [Ohio] [Republicans] [Spanish-American War] [United States History] [Taxation] [Ohio Governors] [Conservatives] [Gilded Age] [Progressive Era] [Republican Governors] [Former Governors]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/28/2023 22:53:07 | 26 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/William_McKinley | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF