Spinal Muscular Atrophy

From Mdwiki

From Mdwiki

| Spinal muscular atrophy | |

|---|---|

| Other names: Autosomal recessive proximal spinal muscular atrophy, 5q spinal muscular atrophy | |

| |

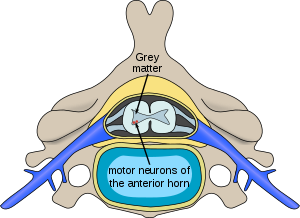

| Location of neurons affected by spinal muscular atrophy in the spinal cord | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | Progressive muscle weakness[1] |

| Complications | Scoliosis, joint contractures, pneumonia[2] |

| Types | Type 0 to type 4[2] |

| Causes | Mutation in SMN1[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Genetic testing[1] |

| Differential diagnosis | Congenital muscular dystrophy, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, Prader-Willi syndrome[2] |

| Treatment | Supportive care, medications[1] |

| Medication | Nusinersen, onasemnogene abeparvovec[3][4] |

| Prognosis | Varies by type[2] |

| Frequency | 1 in 10,000 people[2] |

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a group of neuromuscular disorders that result in the loss of motor neurons and progressive muscle wasting.[1] The severity of symptoms and age of onset varies by the type.[1] Some types are apparent at or before birth while others are not apparent until adulthood.[1] All generally result in worsening muscle weakness associated with muscle twitching.[1][3] Arm, leg and respiratory muscles are generally affected first.[3][5] Associated problems may include problems with swallowing, scoliosis, and joint contractures.[2][5] SMA is a leading genetic cause of death in infants.[4]

Spinal muscular atrophy is due to a genetic defect in the SMN1 gene.[1][2] They are generally inherited from a person's parents in an autosomal recessive manner.[1] In 2% of cases, one of the mutations occurs during early development and one is inherited from a parent.[6] The SMN1 gene encodes SMN, a protein necessary for survival of motor neurons.[5] Loss of these neurons prevents the sending of signals between the brain and skeletal muscles.[5] Diagnosis is suspected based on symptoms and confirmed by genetic testing.[1]

Treatments include supportive care such as physical therapy, nutrition support, and mechanical ventilation.[1] The medication nusinersen, which is injected around the spinal cord, slows the progression of the disease and improves muscle function.[1][3] In 2019, the gene therapy onasemnogene abeparvovec was approved in the US as a treatment for children under 24 months.[4] Outcomes vary by type from a life expectancy of a few months to mild muscle weakness with a normal life expectancy.[5] The condition affects about 1 in 10,000 people at birth.[2]

Classification[edit | edit source]

SMA manifests over a wide range of severity, affecting infants through adults, the most commonly used classification is as follows:

| Type | Eponym | Usual age of onset | Characteristics | OMIM/Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMA 0 | Prenatal | A very rare form whose symptoms become apparent before birth (reduced foetal movement). Affected children typically have atrial septal defects and usually survive only a few weeks due to respiratory problems. | no OMIM/[7] | |

| SMA 1 (Infantile) |

Werdnig–Hoffmann disease | 0–6 months | The severe form manifests in the first months of life. Children never learn to sit unsupported. Rapid motor neuron death causes inefficiency of the major bodily organs – especially of the respiratory system. Pneumonia-induced respiratory failure is the most frequent cause of death. Untreated and without respiratory support, babies diagnosed with SMA type 1 do not generally survive past two years of age. | 253300 |

| SMA 2 (Intermediate) |

Infantile Chronic form SMA | 6–18 months | The intermediate form affects people who were able to maintain a sitting position at least some time in their life but never learned to walk unsupported. The onset of weakness is usually noticed some time between 6 and 18 months of life. The progress is known to vary greatly, some people gradually grow weaker over time while others through careful maintenance remain relatively stable. Body muscles are weakened, and the respiratory system is a major concern. Life expectancy is reduced but most people with SMA 2 live well into adulthood. | 253550 |

| SMA 3 (Juvenile) |

Kugelberg–Welander disease | >18 months | The juvenile form usually manifests after 18 months of age and describes people who have been able to walk without support at least for some time in their lives, even if they later lost this ability. Respiratory involvement occurs in SMA 3, as do hand tremors. | 253400 |

| SMA 4 (Adult onset) |

Autosomal Recessive Proximal adult SMA | Adulthood | The adult-onset form usually manifests after the third decade of life with gradual weakening of leg muscles. slow disease progression. | 271150 |

Motor development and disease progression in people with SMA is usually assessed using validated functional scales – CHOP-INTEND (The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Infant Test of Neuromuscular Disorders)[8] or HINE (Hammersmith Infant Neurological Examination) in infants[9]; and either the MFM (Motor Function Measure)[10] or one of a few variants of the HFMS (Hammersmith Functional Motor Scale) in patients[11].

The eponymous label Werdnig–Hoffmann disease (sometimes misspelled with a single n) refers to the earliest clinical descriptions of childhood SMA by Johann Hoffmann and Guido Werdnig. The eponymous term Kugelberg–Welander disease is after Erik Klas Hendrik Kugelberg (1913–1983) and Lisa Welander (1909–2001), who distinguished SMA from muscular dystrophy.[12]

Signs and symptoms[edit | edit source]

.jpg)

The symptoms vary depending on the SMA type,[3] below are most common in the severe SMA type 0/I:

- Areflexia[13]

- Proximal amyotrophy[13]

- Severe neonatal hypotonia[6]

- Atrial septal defects[6]

- Respiratory insufficiency[13]

- Bell-shaped torso (caused by using only abdominal muscles for respiration) in severe SMA type 1[6]

- Decreased fetal movements[6]

- Mild joint contraction[6]

Association[edit | edit source]

Although the heart is not a matter of routine concern, a link between SMA and certain heart conditions has been suggested.[14]Children with SMA cognitive development can be slightly faster, and certain aspects of their intelligence are above the average.[15]

Genetics[edit | edit source]

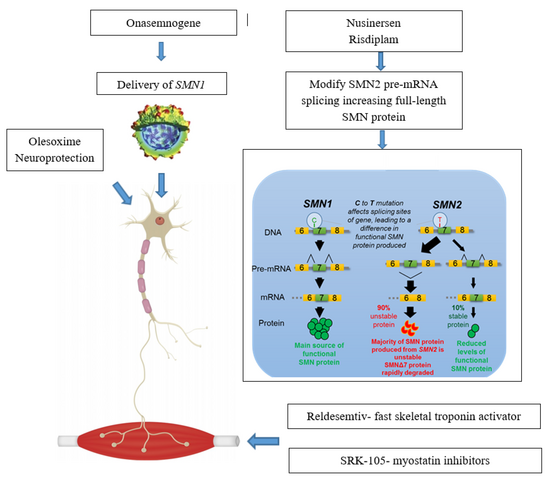

Spinal muscular atrophy is linked to a genetic mutation in the SMN1 gene.[16] Human chromosome 5 contains two nearly identical genes at location 5q13: a telomeric copy SMN1 and a centromeric copy SMN2. In healthy individuals, the SMN1 gene codes the survival of motor neuron protein (SMN) which, as its name says, plays a crucial role in survival of motor neurons. The SMN2 gene, on the other hand – due to a variation in a single nucleotide (840.C→T) – undergoes alternative splicing at the junction of intron 6 to exon 8, with only 10–20% of SMN2 transcripts coding a fully functional survival of motor neuron protein (SMN-fl) and 80–90% of transcripts resulting in a truncated protein compound (SMNΔ7) which is rapidly degraded in the cell.[17]

In individuals affected by SMA, the SMN1 gene is mutated in such a way that it is unable to correctly code the SMN protein – due to either a deletion occurring at exon 7[18] or to other point mutations (frequently resulting in the functional conversion of the SMN1 sequence into SMN2)[19]. Almost all people, however, have at least one functional copy of the SMN2 gene which still codes small amounts of SMN protein – allowing some neurons to survive.[20] In the long run, however, reduced availability of the SMN protein results in gradual death of motor neuron cells in the anterior horn of spinal cord. Muscles that depend on these motor neurons for neural input now have decreased innervation, and therefore have decreased input from the central nervous system (CNS). Decreased impulse transmission through the motor neurons leads to decreased contractile activity of the denervated muscle, consequently, denervated muscles undergo progressive atrophy (waste away).[2][21]

Muscles of lower extremities are usually affected first, followed by muscles of upper extremities, spine and neck and, in more severe cases, pulmonary and mastication muscles. Proximal muscles are always affected earlier and to a greater degree than distal.[22][23]

The severity of SMA symptoms is broadly related to how well the remaining SMN2 genes can make up for the loss of function of SMN1. This is partly related to the number of SMN2 gene copies present on the chromosome. Whilst healthy individuals carry two SMN2 gene copies, people with SMA can have anything between 1 and 4 (or more) of them, with the greater the number of SMN2 copies, the milder the disease severity. Thus, most SMA type I babies have one or two SMN2 copies; people with SMA II and III usually have at least three SMN2 copies; and people with SMA IV normally have at least four of them. However, the correlation between symptom severity and SMN2 copy number is not absolute, and there seem to exist other factors affecting the disease phenotype.[24]

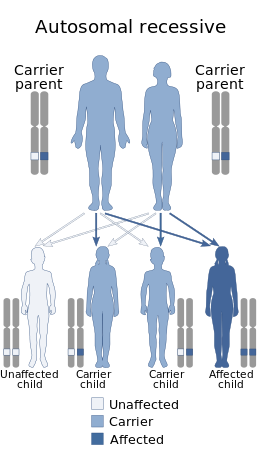

Spinal muscular atrophy is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, which means that the defective gene is located on an autosome. Two copies of the defective gene – one from each parent – are required to inherit the disorder: the parents may be carriers and not personally affected.[6] [25]SMA seems to appear de novo (i.e., without any hereditary causes) in around 2% of cases.[6]Affected siblings usually have a very similar form of SMA.[26] However, occurrences of different SMA types among siblings do exist – while rare[27]

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The most severe manifestation on the SMA spectrum can be noticeable to mothers late in their pregnancy by reduced or absent fetal movements. Symptoms are critical (including respiratory distress and poor feeding) which usually result in death within weeks, in contrast to the mildest phenotype of SMA (adult-onset), where muscle weakness may present after decades and progress to the use of a wheelchair but life expectancy is unchanged.[28]Some common clinical manifestations of the SMA spectrum that prompt diagnostic genetic testing:

- Progressive bilateral muscle weakness (Usually upper arms & legs more so than hands and feet) preceded by an asymptomatic period (all but most severe type 0)[28]

- Areflexia/hyporeflexia[6]

- hypotonia associated with absent reflexes.[6]

While the above symptoms point towards SMA, the diagnosis can only be confirmed with absolute certainty through genetic testing for bi-allelic deletion of exon 7 of the SMN1 gene which is the cause.[6] Genetic testing can be carried out using a blood sample, and Multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA).[29][6]

Screening[edit | edit source]

Preimplantation testing[edit | edit source]

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis can be used to screen for SMA-affected embryos during in-vitro fertilisation.[30]

Prenatal testing[edit | edit source]

Prenatal testing for SMA is possible through chorionic villus sampling, and other methods.[31]: 64

Carrier testing[edit | edit source]

Those at risk of being carriers of SMN1 deletion, and thus at risk of having offspring affected by SMA, can undergo carrier analysis using a blood or saliva sample. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends all people thinking of becoming pregnant be tested to see if they are a carrier.[30]However, genetic testing will not be able to identify all individuals at risk since about 2% of cases are caused by de novo mutations and 5% of the normal populations have two copies of SMN1 on the same chromosome, which makes it possible to be a carrier by having one chromosome with two copies and a second chromosome with zero copies. This situation will lead to a false negative result, as the carrier status will not be correctly detected by a traditional genetic test.[32] [33]

Newborn screening[edit | edit source]

Given the availability of treatments that appear most effective in early stages of the disease, a number of experts have recommended to routinely test all newborn children for SMA.[34][35][36] In 2018, newborn screening for SMA was added to the US list of recommended newborn screening tests[37]. Since 2020, SMA newborn screening is mandated in the Netherlands.[38] Additionally, pilot projects in newborn screening for SMA have been conducted in Australia,[39] Belgium,[40] China,[41] Germany,[42] Italy, Japan,[43] Taiwan,[44] and the US.[45]

Management[edit | edit source]

The management of SMA varies based upon the severity and type: the most severe forms (types 0/1), individuals have the greatest muscle weakness requiring prompt intervention, whereas the least severe form (type 4), individuals may not seek the certain aspects of care until later in life.[47]

Medication[edit | edit source]

Nusinersen is used to treat spinal muscular atrophy. It is an antisense nucleotide that modifies the alternative splicing of the SMN2 gene. It is given directly to the central nervous system using an intrathecal injection. Nusinersen prolongs survival and improves motor function in infants with SMA. It was approved in the US in 2016.[48]

Onasemnogene abeparvovec is a gene therapy treatment which uses self-complementary adeno-associated virus type 9 (scAAV-9) as a vector to deliver the SMN1 transgene.[49] As an intravenous formulation, it was approved in 2019 in the US to treat those below 24 months of age.[50] In 2020, approvals in the EU and Japan for the gene therapy occured.[51]

Risdiplam, which is taken by mouth, was approved by the FDA on August 2020.[52][53]

Breathing[edit | edit source]

The respiratory system is the most common system to be affected and the complications are the leading cause of death in SMA types 0/1 and 2. SMA type 3 can have similar respiratory problems, but it is more rare.[22] The complications that arise are due to weakened intercostal muscles because of the lack of stimulation from the nerve. The diaphragm is less affected than the intercostal muscles.[22] Once weakened, the muscles never fully recover the same functional capacity to help in breathing and coughing as well as other functions. Therefore, breathing is more difficult and pose a risk of not getting enough oxygen/shallow breathing and insufficient clearance of airway secretions[31]: 378 . Swallowing muscles can be affected, leading to aspiration coupled with a poor coughing mechanism increases the likelihood of infection/pneumonia.[54][55] Mobilizing and clearing secretions involve manual or mechanical chest physiotherapy with postural drainage, and manual or mechanical cough assistance device. To assist in breathing, non-invasive ventilation (BiPAP) is frequently used and tracheostomy may be sometimes performed in more severe cases[56]

Nutrition[edit | edit source]

The more severe the type of SMA, are more likely to have nutrition related health issues. Health issues can include difficulty in feeding, jaw opening, chewing and swallowing. Individuals with such difficulties can be at increase risk of over or undernutrition, and failure to thrive.[57] Other nutritional issues, include food not passing through the stomach quickly enough, constipation,and vomiting.[58] Therein, it could be necessary in SMA type II and people with more severe type III to have a feeding tube or gastrostomy.[59]Additionally, metabolic abnormalities resulting from SMA impair β-oxidation of fatty acids in muscles and can lead to muscle damage[31] It is suggested that people with SMA, especially those with more severe forms of the disease, reduce intake of fat and avoid prolonged fasting (i.e., eat more frequently than healthy people)[60]

Orthopaedics[edit | edit source]

Skeletal problems associated with weak muscles in SMA include tight joints with limited range of movement, hip dislocations, spinal deformity, osteopenia, an increase risk of fractures and pain.[22] Weak muscles that normally stabilize joints such as the vertebral column lead to development of kyphosis and/or scoliosis and joint contracture.[22] Spine fusion is sometimes performed in children with SMA once they reach a certain age to relieve the pressure of the deformed spine.[61] Furthermore, immobile individuals, posture and position on mobility devices as well as range of motion exercises, and bone strengthening can be important to prevent complications[62]. People with SMA might also benefit greatly from various forms of physiotherapy, occupational therapy and physical therapy.[63]Orthotic devices can be used to support the body and to aid walking, for example, orthotics such as AFOs (ankle foot orthoses) are used to stabilise the foot and to aid gait, TLSOs (thoracic lumbar sacral orthoses) are used to stabilise the torso.[58]

Other[edit | edit source]

Palliative care in SMA has been standardised in the Consensus Statement for Standard of Care in Spinal Muscular Atrophy[22] which has been recommended for standard adoption worldwide.

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

In lack of pharmacological treatment, people with SMA tend to deteriorate over time. Recently, survival has increased in severe SMA patients with aggressive and proactive supportive respiratory and nutritional support.[64]

The majority of children diagnosed with SMA type 0 and I do not reach the age of 2, recurrent respiratory problems being the primary cause of death.[7][65] With proper care, milder SMA type I cases (which account for approx. 10% of all SMA1 cases) live into adulthood.[66] Long-term survival in SMA type I is not sufficiently evidenced; however, recent advances in respiratory support seem to have brought down mortality.[67]In SMA type II, the course of the disease is slower to progress and life expectancy is less than the healthy population, although many people with SMA type II live long lives.[68][69] SMA type III has normal or near-normal life expectancy if standards of care are followed.[70] Type IV, adult-onset SMA usually means a benign disease course and does not affect life expectancy.[71]

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

The calculated incidence rates of 5.83 per 100,000 live births for SMA type I, accounts for 60% of all SMA types. The overall prevalence of SMA, is in the range of 1 per 10,000 individuals, therefore, approximately one in 50 persons are carriers.[72][73]

Research[edit | edit source]

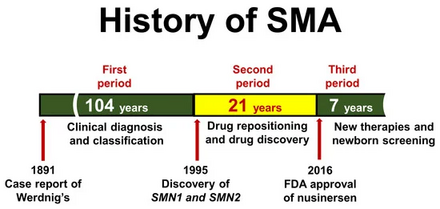

Since the underlying genetic cause of SMA was identified in 1995,[75] several therapeutic approaches have been proposed and investigated that primarily focus on increasing the availability of SMN protein in motor neurons.[76] The main research directions are as follows:

SMN1 gene replacement[edit | edit source]

Gene therapy in SMA aims at restoring the SMN1 gene function through inserting specially crafted nucleotide sequence (a SMN1 transgene) into the cell nucleus using a viral vector[77] In 2019 an AAV9 therapy was approved: Onasemnogene abeparvovec.[78]Only one programme has reached the clinical stage. Work on developing gene therapy for SMA is also conducted at the Institut de Myologie in Paris[79]

SMN2 alternative splicing modulation[edit | edit source]

This approach aims at modifying the alternative splicing of the SMN2 gene to force it to code for higher percentage of full-length SMN protein. [80]The following splicing modulators have reached clinical stage development:

- Branaplam (LMI070, NVS-SM1) is a proprietary small-molecule experimental drug administered orally and being developed by Novartis. As of 2020[update] the compound remains in clinical trial in infants with SMA type 1 [81][82]

SMN2 gene activation[edit | edit source]

This approach aims at increasing expression (activity) of the SMN2 gene, thus increasing the amount of full-length SMN protein available:

- Oral salbutamol (albuterol), a popular asthma medicine, showed therapeutic potential in SMA both in vitro[83] and in three small-scale clinical trials involving patients with SMA types 2 and 3,[84][85][86] besides offering respiratory benefits.

A few compounds initially showed promise but failed to demonstrate efficacy in clinical trials:

- Butyrates (sodium butyrate and sodium phenylbutyrate) held some promise in in vitro studies[87][88] but a clinical trial in symptomatic people did not confirm their efficacy.[89]

- Valproic acid (VPA) was used in SMA on an experimental basis in the 1990s and 2000s because in vitro research suggested its moderate effectiveness.[90][91] However, it demonstrated no efficacy in achievable concentrations when subjected to a large clinical trial.[92][93] It has also been proposed that it may be effective in a subset of people with SMA but its action may be suppressed by fatty acid translocase in others.[94] It is currently not used due to the risk of severe side effects related to long-term use. A 2019 meta-analysis suggested that VPA may offer benefits, even without improving functional score.[95]

- Hydroxycarbamide (hydroxyurea) was shown effective in mouse models[96] and subsequently commercially researched by Novo Nordisk, Denmark, but demonstrated no effect on people with SMA in subsequent clinical trials.[97]

SMN stabilisation[edit | edit source]

SMN stabilisation aims at stabilising the SMNΔ7 protein, the short-lived defective protein coded by the SMN2 gene, so that it is able to sustain neuronal cells.[98]No compounds have been taken forward to the clinical stage. Aminoglycosides showed capability to increase SMN protein availability in two studies.[99][100] Indoprofen offered some promise in vitro.[101]

Neuroprotection[edit | edit source]

Neuroprotective drugs aim at enabling the survival of motor neurons even with low levels of SMN protein.[102]Olesoxime is a proprietary neuroprotective compound developed by the French company Trophos, later acquired by Hoffmann-La Roche, which showed stabilising effect in a phase-II clinical trial involving people with SMA types 2 and 3. Its development was discontinued in 2018 in view of competition with Spinraza and worse than expected data coming from an open-label extension trial.[103]

Of clinically studied compounds which did not show efficacy, thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) held some promise in an open-label uncontrolled clinical trial[104][105] but did not prove effective in a subsequent double-blind placebo-controlled trial.[106] Riluzole, a drug that has mild clinical benefit in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, was proposed to be similarly tested in SMA,[107][108] however a 2008–2010 trial in SMA types 2 and 3[109] was stopped early due to lack of satisfactory results.[110] Compounds that had some neuroprotective effect in in vitro research but never moved to in vivo studies include β-lactam antibiotics (e.g., ceftriaxone)[111][112] and follistatin.[113]

Muscle restoration[edit | edit source]

This approach aims to counter the effect of SMA by targeting the muscle tissue instead of neurons, CK-2127107 (CK-107) is a skeletal troponin activator developed by Cytokinetics in cooperation with Astellas. The drug aims at increasing muscle reactivity despite lowered neural signaling; on August 2020 the trial phase was completed[114]

Stem cells[edit | edit source]

In 2013–2014, a small number of SMA1 children in Italy received court-mandated stem cell injections following the Stamina scam, but the treatment was reported having no effect.[115][116] The medical consensus is that such procedures offer no clinical benefit whilst carrying significant risk, therefore people with SMA are advised against them.[117][118]

Registries[edit | edit source]

People with SMA in the European Union can participate in clinical research by entering their details into registries managed by TREAT-NMD.[119]

See also[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 "Spinal muscular atrophy". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program. Archived from the original on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 "Spinal Muscular Atrophy". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "Spinal Muscular Atrophy Fact Sheet | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". NINDS. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "FDA approves innovative gene therapy to treat pediatric patients with spinal muscular atrophy, a rare disease and leading genetic cause of infant mortality". FDA. 24 May 2019. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 "Spinal muscular atrophy". Genetics Home Reference. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 Prior, Thomas W.; Leach, Meganne E.; Finanger, Erika (1993). "Spinal Muscular Atrophy". GeneReviews®. University of Washington, Seattle. Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Barohn, Richard J. Motor Neuron Disease, An Issue of Neurologic Clinics, E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 833. ISBN 978-0-323-41345-9. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ↑ Glanzman, A.M.; Mazzone, E.; Main, M.; Pelliccioni, M.; Wood, J.; Swoboda, K.J.; Scott, C.; Pane, M.; Messina, S.; Bertini, E.; Mercuri, E.; Finkel, R.S. "The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Infant Test of Neuromuscular Disorders (CHOP INTEND): Test development and reliability". Neuromuscular Disorders. 20 (3): 155–161. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2009.11.014. ISSN 0960-8966. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Roger N.; Pascual, Juan M. Rosenberg's Molecular and Genetic Basis of Neurological and Psychiatric Disease: Volume 2. Academic Press. p. 387. ISBN 978-0-12-813867-0. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ↑ Vuillerot, Carole; Payan, Christine; Iwaz, Jean; Ecochard, René; Bérard, Carole (August 2013). "Responsiveness of the motor function measure in patients with spinal muscular atrophy". Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 94 (8): 1555–1561. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2013.01.014. ISSN 1532-821X. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ↑ Neuromuscular disorders of infancy, childhood, and adolescence : a clinician's approach (Second ed.). London: Elsevier. 2014. p. 134. ISBN 9780124171275. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ↑ Dubowitz V (January 2009). "Ramblings in the history of spinal muscular atrophy". Neuromuscular Disorders. 19 (1): 69–73. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2008.10.004. PMID 18951794.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "Spinal muscular atrophy 1 | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ↑ Wijngaarde, C. A.; Blank, A. C.; Stam, M.; Wadman, R. I.; van den Berg, L. H.; van der Pol, W. L. (11 April 2017). "Cardiac pathology in spinal muscular atrophy: a systematic review". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 12. doi:10.1186/s13023-017-0613-5. ISSN 1750-1172. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ↑ "Spinal Muscular Atrophy Clinical Presentation: History, Physical, Causes". emedicine.medscape.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ↑ "SMN1 gene: MedlinePlus Genetics". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ↑ "Spinal muscular atrophy". Genetics Home Reference. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ↑ "SMN1 survival of motor neuron 1, telomeric [Homo sapiens (human)] - Gene - NCBI". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ↑ Love, Seth; Louis, David; Ellison, David W. Greenfield's Neuropathology, 2-Volume Set, Eighth Edition. CRC Press. p. 965. ISBN 978-0-340-90681-1. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ↑ Kolb, Stephen J.; Kissel, John T. "Spinal Muscular Atrophy". Archives of neurology. 68 (8). doi:10.1001/archneurol.2011.74. ISSN 0003-9942. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ↑ Shababi, Monir; Lorson, Christian L.; Rudnik-Schöneborn, Sabine S. (January 2014). "Spinal muscular atrophy: a motor neuron disorder or a multi-organ disease?". Journal of Anatomy. 224 (1): 15–28. doi:10.1111/joa.12083. ISSN 1469-7580. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 Wang CH, Finkel RS, Bertini ES, Schroth M, Simonds A, Wong B, Aloysius A, Morrison L, Main M, Crawford TO, Trela A (August 2007). "Consensus statement for standard of care in spinal muscular atrophy". Journal of Child Neurology. 22 (8): 1027–49. doi:10.1177/0883073807305788. PMID 17761659.

- ↑ "Motor Neuron Diseases Fact Sheet | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". www.ninds.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ↑ Jedrzejowska M, Milewski M, Zimowski J, Borkowska J, Kostera-Pruszczyk A, Sielska D, Jurek M, Hausmanowa-Petrusewicz I (2009). "Phenotype modifiers of spinal muscular atrophy: the number of SMN2 gene copies, deletion in the NAIP gene and probably gender influence the course of the disease". Acta Biochimica Polonica. 56 (1): 103–8. doi:10.18388/abp.2009_2521. PMID 19287802.

- ↑ "Autosomal recessive: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ↑ Anderson, J. R. Atlas of Skeletal Muscle Pathology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 44. ISBN 978-94-009-4866-2. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ↑ Jones, Cynthia C.; Cook, Suzanne F.; Jarecki, Jill; Belter, Lisa; Reyna, Sandra P.; Staropoli, John; Farwell, Wildon; Hobby, Kenneth (2020). "Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) Subtype Concordance in Siblings: Findings From the Cure SMA Cohort". Journal of Neuromuscular Diseases. 7 (1): 33–40. doi:10.3233/JND-190399. ISSN 2214-3602. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Ottesen EW (January 2017). "ISS-N1 makes the First FDA-approved Drug for Spinal Muscular Atrophy". Translational Neuroscience. 8 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1515/tnsci-2017-0001. PMC 5382937. PMID 28400976.

- ↑ "Spinal Muscular Atrophy". NCBI NLM NIH. NIH. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "Carrier Screening for Spinal Muscular Atrophy". www.acog.org. Archived from the original on 14 August 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Sumner, Charlotte J.; Paushkin, Sergey; Ko, Chien-Ping. Spinal Muscular Atrophy: Disease Mechanisms and Therapy. Academic Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-12-803686-0. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ↑ Prior TW (November 2008). "Carrier screening for spinal muscular atrophy". Genetics in Medicine. 10 (11): 840–2. doi:10.1097/GIM.0b013e318188d069. PMC 3110347. PMID 18941424.

- ↑ Ar Rochmah M, Awano H, Awaya T, Harahap NI, Morisada N, Bouike Y, Saito T, Kubo Y, Saito K, Lai PS, Morioka I, Iijima K, Nishio H, Shinohara M (November 2017). "Spinal muscular atrophy carriers with two SMN1 copies". Brain & Development. 39 (10): 851–860. doi:10.1016/j.braindev.2017.06.002. PMID 28676237.

- ↑ Serra-Juhe C, Tizzano EF (December 2019). "Perspectives in genetic counseling for spinal muscular atrophy in the new therapeutic era: early pre-symptomatic intervention and test in minors". European Journal of Human Genetics. 27 (12): 1774–1782. doi:10.1038/s41431-019-0415-4. PMC 6871529. PMID 31053787. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ Glascock J, Sampson J, Haidet-Phillips A, Connolly A, Darras B, Day J, et al. (29 May 2018). "Treatment Algorithm for Infants Diagnosed with Spinal Muscular Atrophy through Newborn Screening". Journal of Neuromuscular Diseases. 5 (2): 145–158. doi:10.3233/JND-180304. PMC 6004919. PMID 29614695. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ↑ Dangouloff T, Burghes A, Tizzano EF, Servais L (January 2020). "244th ENMC international workshop: Newborn screening in spinal muscular atrophy May 10-12, 2019, Hoofdorp, The Netherlands". Neuromuscular Disorders. 30 (1): 93–103. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2019.11.002. PMID 31882184. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ "Recommended Uniform Screening Panel". Official web site of the U.S. Health Resources & Services Administration. 3 July 2017. Archived from the original on 2 May 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport (23 July 2019). "Neonatal screening for spinal muscular atrophy - Advisory report - The Health Council of the Netherlands". www.healthcouncil.nl. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ Kariyawasam DS, Russell JS, Wiley V, Alexander IE, Farrar MA (March 2020). "The implementation of newborn screening for spinal muscular atrophy: the Australian experience". Genetics in Medicine. 22 (3): 557–565. doi:10.1038/s41436-019-0673-0. PMID 31607747. Archived from the original on 17 November 2020. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ Boemer F, Caberg JH, Dideberg V, Dardenne D, Bours V, Hiligsmann M, et al. (May 2019). "Newborn screening for SMA in Southern Belgium". Neuromuscular Disorders. 29 (5): 343–349. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2019.02.003. PMID 31030938. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ Lin Y, Lin CH, Yin X, Zhu L, Yang J, Shen Y, et al. (2019). "Newborn Screening for Spinal Muscular Atrophy in China Using DNA Mass Spectrometry". Frontiers in Genetics. 10: 1255. doi:10.3389/fgene.2019.01255. PMC 6928056. PMID 31921298. Archived from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ↑ Vill K, Kölbel H, Schwartz O, Blaschek A, Olgemöller B, Harms E, et al. (31 October 2019). "One Year of Newborn Screening for SMA - Results of a German Pilot Project". Journal of Neuromuscular Diseases. 6 (4): 503–515. doi:10.3233/JND-190428. PMC 6918901. PMID 31594245. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ↑ Shinohara M, Niba ET, Wijaya YO, Takayama I, Mitsuishi C, Kumasaka S, Kondo Y, Takatera A, Hokuto I, Morioka I, Ogiwara K (December 2019). "A Novel System for Spinal Muscular Atrophy Screening in Newborns: Japanese Pilot Study". International Journal of Neonatal Screening. 5 (4): 41. doi:10.3390/ijns5040041.

- ↑ Chien YH, Chiang SC, Weng WC, Lee NC, Lin CJ, Hsieh WS, et al. (November 2017). "Presymptomatic Diagnosis of Spinal Muscular Atrophy Through Newborn Screening". The Journal of Pediatrics. 190: 124–129.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.06.042. PMID 28711173.

- ↑ Kraszewski JN, Kay DM, Stevens CF, Koval C, Haser B, Ortiz V, et al. (June 2018). "Pilot study of population-based newborn screening for spinal muscular atrophy in New York state". Genetics in Medicine. 20 (6): 608–613. doi:10.1038/gim.2017.152. PMID 29758563.

- ↑ Messina, Sonia; Sframeli, Maria (July 2020). "New Treatments in Spinal Muscular Atrophy: Positive Results and New Challenges". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 9 (7): 2222. doi:10.3390/jcm9072222. ISSN 2077-0383.

- ↑ Schorling, David C.; Pechmann, Astrid; Kirschner, Janbernd. "Advances in Treatment of Spinal Muscular Atrophy – New Phenotypes, New Challenges, New Implications for Care". Journal of Neuromuscular Diseases. 7 (1): 1–13. doi:10.3233/JND-190424. ISSN 2214-3599. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ↑ Neil, Erin E.; Bisaccia, Elizabeth K. (May 2019). "Nusinersen: A Novel Antisense Oligonucleotide for the Treatment of Spinal Muscular Atrophy". The journal of pediatric pharmacology and therapeutics: JPPT: the official journal of PPAG. 24 (3): 194–203. doi:10.5863/1551-6776-24.3.194. ISSN 1551-6776. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ↑ Hoy, Sheridan M. (July 2019). "Onasemnogene Abeparvovec: First Global Approval". Drugs. 79 (11): 1255–1262. doi:10.1007/s40265-019-01162-5. ISSN 1179-1950. Archived from the original on 26 May 2021. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ↑ Commissioner, Office of the (24 March 2020). "FDA approves innovative gene therapy to treat pediatric patients with spinal muscular atrophy, a rare disease and leading genetic cause of infant mortality". FDA. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ↑ "Novartis claims EU approval for SMA gene therapy Zolgensma". PMLive. 19 May 2020. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ↑ "Positive two-year data for Evrysdi in infants with Type 1 SMA". www.thepharmaletter.com. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ↑ Commissioner, Office of the (7 August 2020). "FDA Approves Oral Treatment for Spinal Muscular Atrophy". FDA. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ↑ Choi, Young-Ah; Suh, Dong In; Chae, Jong-Hee; Shin, Hyung-Ik (1 March 2020). "Trajectory of change in the swallowing status in spinal muscular atrophy type I". International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 130: 109818. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.109818. ISSN 0165-5876. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ↑ Benson, Janette B.; Haith, Marshall M. Diseases and Disorders in Infancy and Early Childhood. Academic Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-12-378567-1. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ↑ Lemoine, Tara J.; Swoboda, Kathryn J.; Bratton, Susan L.; Holubkov, Richard; Mundorff, Michael; Srivastava, Rajendu. "Spinal muscular atrophy type 1: Are proactive respiratory interventions associated with longer survival?". Pediatric critical care medicine : a journal of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical Care Societies. 13 (3): e161–e165. doi:10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182388ad1. ISSN 1529-7535. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ↑ Carrau, Ricardo L.; Murry, Thomas; Howell, Rebecca J. Comprehensive Management of Swallowing Disorders, Second Edition. Plural Publishing. p. 191. ISBN 978-1-944883-25-6. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 "Diagnosis and management of spinal muscular atrophy: Part 1: Recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, orthopedic and nutritional care". Neuromuscular Disorders. 28 (2): 103–115. 1 February 2018. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2017.11.005. ISSN 0960-8966. Archived from the original on 27 May 2019. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ↑ Chen YS, Shih HH, Chen TH, Kuo CH, Jong YJ (March 2012). "Prevalence and risk factors for feeding and swallowing difficulties in spinal muscular atrophy types II and III". The Journal of Pediatrics. 160 (3): 447–451.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.08.016. PMID 21924737.

- ↑ Leighton S (2003). "Nutrition issues associated with spinal muscular atrophy". Nutrition & Dietetics. 60 (2): 92–96.

- ↑ "Spinal muscular atrophy - Treatment". nhs.uk. 24 September 2018. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ↑ Maria, Bernard L. Current Management in Child Neurology. PMPH-USA. p. 477. ISBN 978-1-60795-000-4. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ↑ Daroff, Robert B. Bradley's Neurology in Clinical Practice E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1503. ISBN 978-0-323-33916-2. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ↑ Darras, Basil; Finkel, Richard (2017). Spinal Muscular Atrophy. United Kingdom, United States: Elsevier. p. 417. ISBN 978-0-12-803685-3.

- ↑ Gupta, Piyush; Menon, P. S. N.; Ramji, Siddarth; Lodha, Rakesh. PG Textbook of Pediatrics: Volume 3: Systemic Disorders and Social Pediatrics. JP Medical Ltd. p. 2247. ISBN 978-93-5152-956-9. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ↑ Bach JR (May 2007). "Medical considerations of long-term survival of Werdnig-Hoffmann disease". American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 86 (5): 349–55. doi:10.1097/PHM.0b013e31804b1d66. PMID 17449979.

- ↑ Park, Hyun Bin; Lee, Soon Min; Lee, Jin Sung; Park, Min Soo; Park, Kook In; Namgung, Ran; Lee, Chul (November 2010). "Survival analysis of spinal muscular atrophy type I". Korean Journal of Pediatrics. 53 (11): 965–970. doi:10.3345/kjp.2010.53.11.965. ISSN 1738-1061. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ↑ "Spinal muscular atrophy - Types". nhs.uk. 23 October 2017. Archived from the original on 10 October 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ↑ "Spinal Muscular Atrophy Information Page | National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke". www.ninds.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 9 October 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ↑ "Spinal muscular atrophy type 3 | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 16 October 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ↑ "Spinal muscular atrophy type 4 | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ↑ Verhaart, Ingrid E. C.; Robertson, Agata; Wilson, Ian J.; Aartsma-Rus, Annemieke; Cameron, Shona; Jones, Cynthia C.; Cook, Suzanne F.; Lochmüller, Hanns (4 July 2017). "Prevalence, incidence and carrier frequency of 5q–linked spinal muscular atrophy – a literature review". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 12 (1): 124. doi:10.1186/s13023-017-0671-8. ISSN 1750-1172. Archived from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ↑ Su YN, Hung CC, Lin SY, Chen FY, Chern JP, Tsai C, Chang TS, Yang CC, Li H, Ho HN, Lee CN (February 2011). Schrijver I (ed.). "Carrier screening for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) in 107,611 pregnant women during the period 2005-2009: a prospective population-based cohort study". PLOS ONE. 6 (2): e17067. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...617067S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017067. PMC 3045421. PMID 21364876.

- ↑ Nishio, Hisahide; Niba, Emma Tabe Eko; Saito, Toshio; Okamoto, Kentaro; Takeshima, Yasuhiro; Awano, Hiroyuki (January 2023). "Spinal Muscular Atrophy: The Past, Present, and Future of Diagnosis and Treatment". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 24 (15): 11939. doi:10.3390/ijms241511939. ISSN 1422-0067.

- ↑ "Spinal Muscular Atrophy". Medscape. Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ↑ d'Ydewalle C, Sumner CJ (April 2015). "Spinal Muscular Atrophy Therapeutics: Where do we Stand?". Neurotherapeutics. 12 (2): 303–16. doi:10.1007/s13311-015-0337-y. PMC 4404440. PMID 25631888.

- ↑ Rao, Vamshi K.; Kapp, Daniel; Schroth, Mary (December 2018). "Gene Therapy for Spinal Muscular Atrophy: An Emerging Treatment Option for a Devastating Disease". Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy. 24 (12-a Suppl): S3–S16. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2018.24.12-a.s3. ISSN 2376-1032. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ↑ "$2.1m Novartis gene therapy to become world's most expensive drug". The Guardian. Reuters. 25 May 2019. ISSN 0261-3077.

- ↑ Benkhelifa-Ziyyat S, Besse A, Roda M, Duque S, Astord S, Carcenac R, Marais T, Barkats M (February 2013). "Intramuscular scAAV9-SMN injection mediates widespread gene delivery to the spinal cord and decreases disease severity in SMA mice". Molecular Therapy. 21 (2): 282–90. doi:10.1038/mt.2012.261. PMC 3594018. PMID 23295949.

- ↑ Khoo, Bernard; Krainer, Adrian R. "Splicing therapeutics in SMN2 and APOB". Current opinion in molecular therapeutics. 11 (2): 108–115. ISSN 1464-8431. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ↑ "Branaplam". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ↑ "An Open Label Multi-part First-in-human Study of Oral LMI070 in Infants With Type 1 Spinal Muscular Atrophy". NIH. clinicaltrials.gov. 27 July 2020. Archived from the original on 7 January 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ↑ Angelozzi C, Borgo F, Tiziano FD, Martella A, Neri G, Brahe C (January 2008). "Salbutamol increases SMN mRNA and protein levels in spinal muscular atrophy cells". Journal of Medical Genetics. 45 (1): 29–31. doi:10.1136/jmg.2007.051177. PMID 17932121.

- ↑ Pane M, Staccioli S, Messina S, D'Amico A, Pelliccioni M, Mazzone ES, Cuttini M, Alfieri P, Battini R, Main M, Muntoni F, Bertini E, Villanova M, Mercuri E (July 2008). "Daily salbutamol in young patients with SMA type II". Neuromuscular Disorders. 18 (7): 536–40. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2008.05.004. PMID 18579379.

- ↑ Tiziano FD, Lomastro R, Pinto AM, Messina S, D'Amico A, Fiori S, Angelozzi C, Pane M, Mercuri E, Bertini E, Neri G, Brahe C (December 2010). "Salbutamol increases survival motor neuron (SMN) transcript levels in leucocytes of spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) patients: relevance for clinical trial design". Journal of Medical Genetics. 47 (12): 856–8. doi:10.1136/jmg.2010.080366. PMID 20837492.

- ↑ Morandi L, Abiusi E, Pasanisi MB, Lomastro R, Fiori S, Di Pietro L, Angelini C, Sorarù G, Gaiani A, Mongini T, Vercelli L (2013). "P.6.4 Salbutamol tolerability and efficacy in adult type III SMA patients: Results of a multicentric, molecular and clinical, double-blind, placebo-controlled study". Neuromuscular Disorders. 23 (9–10): 771. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2013.06.475.

- ↑ Andreassi C, Angelozzi C, Tiziano FD, Vitali T, De Vincenzi E, Boninsegna A, Villanova M, Bertini E, Pini A, Neri G, Brahe C (January 2004). "Phenylbutyrate increases SMN expression in vitro: relevance for treatment of spinal muscular atrophy". European Journal of Human Genetics. 12 (1): 59–65. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201102. PMID 14560316.

- ↑ Brahe C, Vitali T, Tiziano FD, Angelozzi C, Pinto AM, Borgo F, Moscato U, Bertini E, Mercuri E, Neri G (February 2005). "Phenylbutyrate increases SMN gene expression in spinal muscular atrophy patients". European Journal of Human Genetics. 13 (2): 256–9. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201320. PMID 15523494.

- ↑ Mercuri E, Bertini E, Messina S, Solari A, D'Amico A, Angelozzi C, Battini R, Berardinelli A, Boffi P, Bruno C, Cini C, Colitto F, Kinali M, Minetti C, Mongini T, Morandi L, Neri G, Orcesi S, Pane M, Pelliccioni M, Pini A, Tiziano FD, Villanova M, Vita G, Brahe C (January 2007). "Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of phenylbutyrate in spinal muscular atrophy". Neurology. 68 (1): 51–5. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000249142.82285.d6. PMID 17082463.

- ↑ Brichta L, Hofmann Y, Hahnen E, Siebzehnrubl FA, Raschke H, Blumcke I, Eyupoglu IY, Wirth B (October 2003). "Valproic acid increases the SMN2 protein level: a well-known drug as a potential therapy for spinal muscular atrophy". Human Molecular Genetics. 12 (19): 2481–9. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddg256. PMID 12915451.

- ↑ Tsai LK, Tsai MS, Ting CH, Li H (November 2008). "Multiple therapeutic effects of valproic acid in spinal muscular atrophy model mice". Journal of Molecular Medicine. 86 (11): 1243–54. doi:10.1007/s00109-008-0388-1. PMID 18649067.

- ↑ Swoboda KJ, Scott CB, Crawford TO, Simard LR, Reyna SP, Krosschell KJ, Acsadi G, Elsheik B, Schroth MK, D'Anjou G, LaSalle B, Prior TW, Sorenson SL, Maczulski JA, Bromberg MB, Chan GM, Kissel JT, et al. (Project Cure Spinal Muscular Atrophy Investigators Network) (August 2010). Boutron I (ed.). "SMA CARNI-VAL trial part I: double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of L-carnitine and valproic acid in spinal muscular atrophy". PLOS ONE. 5 (8): e12140. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...512140S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012140. PMC 2924376. PMID 20808854.

- ↑ Kissel JT, Scott CB, Reyna SP, Crawford TO, Simard LR, Krosschell KJ, Acsadi G, Elsheik B, Schroth MK, D'Anjou G, LaSalle B, Prior TW, Sorenson S, Maczulski JA, Bromberg MB, Chan GM, Swoboda KJ, et al. (Project Cure Spinal Muscular Atrophy Investigators' Network) (2011). "SMA CARNIVAL TRIAL PART II: a prospective, single-armed trial of L-carnitine and valproic acid in ambulatory children with spinal muscular atrophy". PLOS ONE. 6 (7): e21296. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...621296K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0021296. PMC 3130730. PMID 21754985.

- ↑ Garbes L, Heesen L, Hölker I, Bauer T, Schreml J, Zimmermann K, Thoenes M, Walter M, Dimos J, Peitz M, Brüstle O, Heller R, Wirth B (January 2013). "VPA response in SMA is suppressed by the fatty acid translocase CD36". Human Molecular Genetics. 22 (2): 398–407. doi:10.1093/hmg/dds437. PMID 23077215.

- ↑ Elshafay A, Hieu TH, Doheim MF, Kassem MA, ELdoadoa MF, Holloway SK, Abo-Elghar H, Hirayama K, Huy NT (March 2019). "Efficacy and Safety of Valproic Acid for Spinal Muscular Atrophy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". CNS Drugs. 33 (3): 239–250. doi:10.1007/s40263-019-00606-6. PMID 30796634.

- ↑ Grzeschik SM, Ganta M, Prior TW, Heavlin WD, Wang CH (August 2005). "Hydroxyurea enhances SMN2 gene expression in spinal muscular atrophy cells". Annals of Neurology. 58 (2): 194–202. doi:10.1002/ana.20548. PMID 16049920.

- ↑ Chen TH, Chang JG, Yang YH, Mai HH, Liang WC, Wu YC, Wang HY, Huang YB, Wu SM, Chen YC, Yang SN, Jong YJ (December 2010). "Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of hydroxyurea in spinal muscular atrophy". Neurology. 75 (24): 2190–7. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182020332. PMID 21172842.

- ↑ Burnett BG, Muñoz E, Tandon A, Kwon DY, Sumner CJ, Fischbeck KH (March 2009). "Regulation of SMN protein stability". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 29 (5): 1107–15. doi:10.1128/MCB.01262-08. PMC 2643817. PMID 19103745.

- ↑ Mattis VB, Rai R, Wang J, Chang CW, Coady T, Lorson CL (November 2006). "Novel aminoglycosides increase SMN levels in spinal muscular atrophy fibroblasts". Human Genetics. 120 (4): 589–601. doi:10.1007/s00439-006-0245-7. PMID 16951947.

- ↑ Mattis VB, Fosso MY, Chang CW, Lorson CL (November 2009). "Subcutaneous administration of TC007 reduces disease severity in an animal model of SMA". BMC Neuroscience. 10: 142. doi:10.1186/1471-2202-10-142. PMC 2789732. PMID 19948047.

- ↑ Lunn MR, Root DE, Martino AM, Flaherty SP, Kelley BP, Coovert DD, Burghes AH, Man NT, Morris GE, Zhou J, Androphy EJ, Sumner CJ, Stockwell BR (November 2004). "Indoprofen upregulates the survival motor neuron protein through a cyclooxygenase-independent mechanism". Chemistry & Biology. 11 (11): 1489–93. doi:10.1016/j.chembiol.2004.08.024. PMC 3160629. PMID 15555999.

- ↑ Shorrock, Hannah K.; Gillingwater, Thomas H.; Groen, Ewout J. N. (1 March 2018). "Overview of Current Drugs and Molecules in Development for Spinal Muscular Atrophy Therapy". Drugs. 78 (3): 293–305. doi:10.1007/s40265-018-0868-8. ISSN 1179-1950. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ↑ Taylor, Nick P. (1 June 2018). "Roche scraps €120M SMA drug after hitting 'many difficulties'". www.fiercebiotech.com. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ↑ Tzeng AC, Cheng J, Fryczynski H, Niranjan V, Stitik T, Sial A, Takeuchi Y, Foye P, DePrince M, Bach JR (2000). "A study of thyrotropin-releasing hormone for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy: a preliminary report". American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 79 (5): 435–40. doi:10.1097/00002060-200009000-00005. PMID 10994885.

- ↑ Kato Z, Okuda M, Okumura Y, Arai T, Teramoto T, Nishimura M, Kaneko H, Kondo N (August 2009). "Oral administration of the thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) analogue, taltireline hydrate, in spinal muscular atrophy". Journal of Child Neurology. 24 (8): 1010–2. doi:10.1177/0883073809333535. PMID 19666885.

- ↑ Wadman RI, Bosboom WM, van den Berg LH, Wokke LH, Iannaccone ST, Vrancken AF, et al. (The Cochrane Collaboration) (7 December 2011). "Drug treatment for spinal muscular atrophy type I". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006281.pub3.

- ↑ Haddad H, Cifuentes-Diaz C, Miroglio A, Roblot N, Joshi V, Melki J (October 2003). "Riluzole attenuates spinal muscular atrophy disease progression in a mouse model". Muscle & Nerve. 28 (4): 432–7. doi:10.1002/mus.10455. PMID 14506714.

- ↑ Dimitriadi M, Kye MJ, Kalloo G, Yersak JM, Sahin M, Hart AC (April 2013). "The neuroprotective drug riluzole acts via small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels to ameliorate defects in spinal muscular atrophy models". The Journal of Neuroscience. 33 (15): 6557–62. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1536-12.2013. PMC 3652322. PMID 23575853.

- ↑ Clinical trial number NCT00774423 for "Study to Evaluate the Efficacy of Riluzole in Children and Young Adults With Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- ↑ "Riluzole: premiers résultats décevants" (in français). AFM Téléthon. 22 September 2010. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ↑ Nizzardo M, Nardini M, Ronchi D, Salani S, Donadoni C, Fortunato F, Colciago G, Falcone M, Simone C, Riboldi G, Govoni A, Bresolin N, Comi GP, Corti S (June 2011). "Beta-lactam antibiotic offers neuroprotection in a spinal muscular atrophy model by multiple mechanisms" (PDF). Experimental Neurology. 229 (2): 214–25. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.01.017. hdl:2434/425410. PMID 21295027. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- ↑ Hedlund E (September 2011). "The protective effects of β-lactam antibiotics in motor neuron disorders". Experimental Neurology. 231 (1): 14–8. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.06.002. PMID 21693120.

- ↑ Rose FF, Mattis VB, Rindt H, Lorson CL (March 2009). "Delivery of recombinant follistatin lessens disease severity in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy". Human Molecular Genetics. 18 (6): 997–1005. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddn426. PMC 2649020. PMID 19074460.

- ↑ "A Study of CK-2127107 in Patients With Spinal Muscular Atrophy - Study Results - ClinicalTrials.gov". clinicaltrials.gov. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ↑ Carrozzi M, Amaddeo A, Biondi A, Zanus C, Monti F, Alessandro V (November 2012). "Stem cells in severe infantile spinal muscular atrophy (SMA1)". Neuromuscular Disorders. 22 (11): 1032–4. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2012.09.005. PMID 23046997.

- ↑ Mercuri E, Bertini E (December 2012). "Stem cells in severe infantile spinal muscular atrophy". Neuromuscular Disorders. 22 (12): 1105. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2012.11.001. PMID 23206850.

- ↑ Committee for Advanced Therapies and CAT Scientific Secretariat (August 2010). "Use of unregulated stem-cell based medicinal products". Lancet. 376 (9740): 514. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61249-4. PMID 20709228.

- ↑ European Medicines Agency (16 April 2010). "Concerns over unregulated medicinal products containing stem cells" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ↑ "National registries for DMD, SMA and DM". Archived from the original on 22 January 2011.

Further reading[edit | edit source]

- Parano E, Pavone L, Falsaperla R, Trifiletti R, Wang C (August 1996). "Molecular basis of phenotypic heterogeneity in siblings with spinal muscular atrophy". Annals of Neurology. 40 (2): 247–51. doi:10.1002/ana.410400219. PMID 8773609.

- Wang CH, Finkel RS, Bertini ES, Schroth M, Simonds A, Wong B, Aloysius A, Morrison L, Main M, Crawford TO, Trela A (August 2007). "Consensus statement for standard of care in spinal muscular atrophy". Journal of Child Neurology. 22 (8): 1027–49. doi:10.1177/0883073807305788. PMID 17761659.

External links[edit | edit source]

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

Categories: [Spinal muscular atrophy] [Motor neuron diseases] [Autosomal recessive disorders] [Nucleus diseases] [Systemic atrophies primarily affecting the central nervous system] [Neurogenetic disorders] [Neuromuscular disorders] [RTT]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 04/12/2024 21:22:29 | 1 views

☰ Source: https://mdwiki.org/wiki/Spinal_muscular_atrophy | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

KSF

KSF