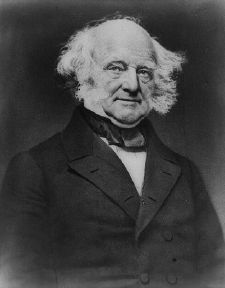

Martin Van Buren

From Nwe

From Nwe

|

|

|

| Term of office | March 4, 1837 – March 3, 1841 |

| Preceded by | Andrew Jackson |

| Succeeded by | William Henry Harrison |

| Date of birth | December 5, 1782 |

| Place of birth | Kinderhook, New York |

| Date of death | July 24, 1862 |

| Place of death | Kinderhook, New York |

| Spouse | Widowed Hannah Hoes Van Buren (daughter-in-law Angelica Van Buren was first lady) |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican, Democratic, and Free Soil |

Martin Van Buren (December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862), nicknamed Old Kinderhook, was the eighth president of the United States. He was a key organizer of the Democratic Party, a dominant figure in the Second Party System, and was the first president not born a British subject or of British ancestry. The Van Burens were a large, struggling family of Dutch descent.

He was the first of a series of eight presidents between Andrew Jackson and Abraham Lincoln who served one term or less. He also was one of the central figures in developing modern political organizations. As Andrew Jackson's secretary of state and then vice president, he was a key figure in building the organizational structure for Jacksonian democracy, particularly in New York State. However, as a president, his administration was largely characterized by the economic hardship of his time, the Panic of 1837.

Relations with Britain and its colonies in Canada also were strained, and Van Buren was voted out of office after four years, with a close popular vote but a rout in the electoral vote. Van Buren ran unsuccessfully for president in 1844 and 1848, and he played a major role in the battles over slavery, ultimately leading the split in the Democratic Party that played a critical role in the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860.

Early Life

Martin Van Buren was born in the village of Kinderhook, New York, approximately 25 miles south of Albany, the state capital. He was the third of five children and a seventh-generation American. His great-great-great-great-grandfather Cornelis had come to the American colonies in 1631 from the Netherlands. Martin's father, Abraham Van Buren, was a farmer and popular tavern-master. His mother Maria Goes Hoes, was a widow who had three sons from a previous marriage.

Van Buren was educated at the common schools and at Kinderhook Academy. He possessed a fine mind and a strong ambition. Van Buren embarked on a legal career at 14 with an apprenticeship to a local attorney, William Peter van Ness. In 1804 he joined his half-brother's law practice in their hometown. Three years later Van Buren married a distant relative and childhood sweetheart, Hannah Hoes. They had five children.

Early political career

Van Buren's career in the New York Senate covered two terms (1812–1820). In 1815, he became the state attorney general, an office that he held until 1819. He had moved from Kinderhook to Hudson, New York, and in 1816 he took up his residence in Albany, where he continued to live until he entered Jackson's cabinet in 1829.

As a member of the state senate, he supported the War of 1812 and drew up a classification act for the enrollment of volunteers. He broke ties with Governor DeWitt Clinton in 1813 and tried to find a way to oppose Clinton's plan for the Erie Canal in 1817. Van Buren supported a bill that raised money for the canal through state bonds, and the bill quickly passed through the legislature with the help of his Tammany Hall compatriots. When the 96-mile stretch of the Erie Canal from Utica to Syracuse, New York opened in 1819, Van Buren took all the credit. His supporters guaranteed money for the canal in 1821, and they drove Clinton from the governor's office.

Van Buren's attitude towards slavery at the time was shown by his January 1820 vote for a resolution opposing the admission of Missouri as a slave state. In the same year, he was chosen a presidential elector. It is at this point that Van Buren's connection began with so-called "machine politics." He was the leading figure in the Albany Regency, a group of politicians who for more than a generation dominated much of the politics of New York and powerfully influenced those of the nation. The group, together with the political clubs such as Tammany Hall that were developing at the same time, played a major role in the development of the "spoils system," an system of political patronage that rewarded supporters with appointments to offices and helped build party loyalty in national, state and local politics. Van Buren did not originate the system but gained the nickname of "Little Magician" for the skill with which he exploited it. He also served as a member of the state constitutional convention, where he opposed the grant of universal male suffrage and tried to keep property requirements.

U.S. Senate and National Politics

In February 1821, Van Buren was elected to the United States Senate. Van Buren at first favored internal improvements and in 1824 proposed a constitutional amendment to authorize such undertakings. The next year, however, he took a position against them. He voted for the tariff of 1824 then gradually abandoned the protectionist position, coming out for "tariffs for revenue only."

In the presidential election of 1824, Van Buren supported William H. Crawford and received the electoral vote of Georgia for vice president, but he shrewdly kept out of the acrimonious controversy that followed the choice of John Quincy Adams as president. Van Buren had originally hoped to block Adams' victory by denying him the state of New York. However, Representative Stephen Van Rensselear swung New York to Adams and thereby the 1824 election. Van Buren recognized early the potential of Andrew Jackson as a presidential candidate.

After the election, Van Buren sought to bring the Crawford and Jackson followers together and strengthened his control as a leader in the Senate. Always notably courteous in his treatment of opponents, he showed no bitterness toward either Adams or Adams' influential congressional supporter Henry Clay; and he voted for Clay's confirmation as secretary of state, notwithstanding Jackson's "corrupt bargain" charge. At the same time, he opposed the Adams-Clay plans for internal improvements and declined to support the proposal for a Panama Congress.

As chairman of the Judiciary Committee, he brought forward a number of measures for the improvement of judicial procedure and, in May 1826, joined with Senator Thomas Hart Benton in presenting a report on executive patronage. In the debate on the "tariff of abominations" in 1828, he took no part but voted for the measure in obedience to instructions from the New York legislature—an action that was cited against him as late as the presidential campaign of 1844.

Van Buren was not an orator, but his more important speeches show careful preparation and his opinions carried weight; the oft-repeated charge that he refrained from declaring himself on crucial questions is hardly borne out by an examination of his senatorial career. In February 1827, he was re-elected to the Senate by a large majority. He became one of the recognized managers of the Jackson campaign, and his tour of Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia in the spring of 1827 won support for Jackson from Crawford. Calling it "substantial reorganization," Van Buren helped create a grassroots style of politicking that we often see today. At the state level, Jackson's committee chairmen would split up the responsibilities around the state and organize volunteers at the local level. "Hurra Boys" would plant hickory trees (in honor of Jackson's nickname, "Old Hickory") or hand out hickory sticks at rallies. Van Buren even had a New York journalist write a campaign piece portraying Jackson as a humble, pious man. "Organization is the secret of victory," an editor in the Adams camp wrote. "By the want of it we have been overthrown." In 1828 Van Buren was elected governor of New York for the term beginning on January 1, 1829, and resigned his seat in the Senate.

The Jackson Cabinet

Following Jackson's election to the presidency in 1828, Van Buren was appointed by Jackson as secretary of state, an office that probably had been assured to him before the election, and he resigned the governorship. He was succeeded in the governorship by his lieutenant governor, Enos T. Throop, a member of the regency. As secretary of state, Van Buren took care to keep on good terms with the "kitchen cabinet," the group of politicians who acted as Jackson's advisers. He won the lasting regard of Jackson by his courtesies to Mrs. John H. Eaton, wife of the Secretary of War, with whom the wives of the cabinet officers had refused to associate. He did not oppose Jackson in the matter of removals from office but was not himself an active "spoilsman." He skillfully avoided entanglement in the imbroglio between Jackson and South Carolina states rights advocate and then–Vice President John C. Calhoun over South Carolina's nullification of a federal tariff.

No diplomatic questions of the first magnitude arose during Van Buren's service as secretary, but the settlement of long-standing claims against France was prepared and trade with the British West Indies colonies was opened. In the controversy over the reauthorization of the Bank of the United States, he sided with Jackson, who opposed the measure. After the breach between Jackson and Calhoun, Van Buren was clearly the most prominent candidate for the vice presidency.

Vice-Presidency

In December 1829, Jackson had already made known his own wish that Van Buren should receive the nomination. In April 1831, Van Buren resigned from his secretary of state position, though he did not leave office until June. In August, he was appointed minister to the Court of St. James (Great Britain), and he arrived in London in September. He was cordially received, but in February, he learned that the Senate had rejected his nomination on January 25. The rejection, ostensibly attributed in large part to Van Buren's instructions to Louis McLane, the American minister to England, regarding the opening of the West Indies trade, was in fact the work of Calhoun, the vice president. And when the vote was taken, enough of the majority refrained from voting to produce a tie and give Calhoun his longed-for "vengeance." No greater impetus than this could have been given to Van Buren's candidacy for the vice-presidency.

After a brief tour through Europe, Van Buren reached New York on July 5, 1832. In May, the Democratic National Convention, the first held by that party, had nominated him for vice president on the Jackson ticket, despite the strong opposition to him that existed in many states. No platform was adopted because the widespread popularity of Jackson was being relied upon to succeed at the polls. His declarations during the campaign were vague regarding the tariff and unfavorable to the United States Bank and to nullification, but he had already somewhat placated the South by denying the right of Congress to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia without the consent of the slave states.

In the election of 1832, Jackson won by a landslide. Jackson was now determined to make Van Buren president in 1836 in order to continue his legacy. In May 1835, Van Buren was unanimously nominated by the Democratic convention at Baltimore. He expressed himself plainly on the questions of slavery and the national bank, at the same time voting, perhaps with a touch of bravado, for a bill offered in 1836 to subject abolition literature in the mails to the laws of the several states. Van Buren’s presidential victory represented a broader victory for Jackson and the party.

Presidency 1837-1841

Policies

Martin Van Buren announced his intention "to follow in the footsteps of his illustrious predecessor," and retained all but one of Jackson's cabinet. Van Buren had few economic tools to deal with the economic crisis of 1837. He succeeded in setting up a system of bonds for the national debt. His party was so split that his 1837 proposal for an "Independent Treasury" system did not pass until 1840. It gave the Treasury control of all federal funds and had a legal tender clause that required by 1843 all payments to be made in legal tender rather than in state bank notes. But the act was repealed in 1841 and never had much impact.

Foreign affairs were complicated when several states defaulted on their state bonds. In Great Britain the banks and government complained, and the United States government responded by declaring it had no responsibility for those bonds. British luminaries such as Charles Dickens denounced the American failure to pay royalties, leading to a negative press in Great Britain regarding the financial honesty of America.

The Caroline Affair involved Canadian rebels using New York bases to attack the government in Canada. On December 29, 1837, Canadian government forces crossed the frontier into the U.S. and burned the steamboat the SS Caroline, which the rebels had been using. One American was killed, and an outburst of anti-British sentiment swept through the United States. Van Buren sent the army to the frontier and closed the rebel bases. Van Buren tried to vigorously enforce the neutrality laws, but American public opinion favored the rebels. Boundary disputes in May brought Canadian and American lumberjacks into conflict in northern Maine. There was little bloodshed in this Aroostook War, but it further inflamed public opinion on both sides.

Van Buren took the blame for hard times, as Whigs ridiculed him as Martin Van Ruin. State elections of 1837 and 1838 were disastrous for the Democrats, and the partial economic recovery in 1839 was offset by a second commercial crisis in that year. Nevertheless, Van Buren controlled his party and was unanimously renominated by the Democrats in 1840. The revolt against Democratic rule led to the election of William Henry Harrison, the Whig candidate.

Administration and Cabinet

| OFFICE | NAME | TERM |

| President | Martin Van Buren | 1837–1841 |

| Vice President | Richard M. Johnson | 1837–1841 |

| Secretary of State | John Forsyth | 1837–1841 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Levi Woodbury | 1837–1841 |

| Secretary of War | Joel Poinsett | 1837–1841 |

| Attorney General | Benjamin Butler | 1837–1838 |

| Felix Grundy | 1838–1840 | |

| Henry D. Gilpin | 1840–1841 | |

| Postmaster General | Amos Kendall | 1837–1840 |

| John M. Niles | 1840–1841 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Mahlon Dickerson | 1837–1838 |

| James K. Paulding | 1838–1841 | |

Supreme Court appointments

Van Buren appointed the following Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- John McKinley – 1838

- Peter Vivian Daniel – 1842

Later life

On the expiration of his term, Van Buren retired to his estate, Lindenwald, in Kinderhook, New York, where he strategized his return to the White House. He seemed to have the advantage for the nomination in 1844; his famous letter of April 27, 1844, in which he frankly opposed the immediate annexation of Texas, though doubtless contributing greatly to his defeat, was not made public until he felt practically sure of the nomination. In the Democratic convention, though he had a majority of the votes, he did not have the two-thirds that the convention required, and after eight ballots his name was withdrawn. James K. Polk received the nomination instead.

In 1848 he was nominated by two minor parties, first by the "Barnburner" faction of the Democrats, then by the Free Soil Party, with whom the "Barnburners" coalesced. He won no electoral votes, but took enough votes in New York to give the state and the election to Zachary Taylor. In the election of 1860, he voted for the fusion ticket in New York that was opposed to Abraham Lincoln, but he could not approve of President Buchanan's course in dealing with secession and eventually supported Lincoln.

After being bedridden with a case of pneumonia since the fall of 1861, Van Buren died of bronchial asthma and heart failure at his Lindenwald estate on July 24, 1862. He is buried in the Kinderhook Cemetery.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Secondary sources

- Cole, Donald B. Martin Van Buren And The American Political System. Eastern National Park and Monument Association, 2004. ISBN 159091029X

- Curtis, James C. The Fox at Bay: Martin Van Buren and the Presidency, 1837-1841. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1970. ISBN 0813112141

- Gammon, Samuel Rhea. The Presidential Campaign of 1832 St. Clair Shores, MI: Scholarly Press, 1972. ISBN 0403006031

- McDougall, Walter A. Freedom Just Around the Corner: A New American History 1525 - 1828. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 2004. ISBN 0060197897

- Niven, John. Martin Van Buren: The Romantic Age of American Politics. American Political Biography Press, 2000. ISBN 0945707258

- Remini, Robert V. Martin Van Buren and the Making of the Democratic Party. New York: Columbia University Press, 1959. ISBN 0231022883

- Schouler, James. History of the United States of America: Under the Constitution vol. 4. 1831-1847. Democrats and Whigs. (1917) Online edition

- Silbey, Joel. Martin Van Buren and the Emergence of American Popular Politics. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002. ISBN 0742522431

- Wilson, Major L. The Presidency of Martin Van Buren. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1984. ISBN 0700602380

Primary sources

- Van Buren, Martin. Autobiography (1918). ISBN 0678005311

- Van Buren, Martin. Inquiry Into the Origin and Course of Political Parties in the United States (1867). ISBN 1418129240 Online edition

External links

All links retrieved November 7, 2022.

- State of the Union Addresses:

- Martin Van Buren National Historic Site (Lindenwald)

- Martin Van Buren: The Greatest American President from independent.org

| Preceded by: Nathan Sanford |

United States Senator 1821 – 1828 |

Succeeded by: Charles E. Dudley |

| Preceded by: Nathaniel Pitcher |

Governor of New York 1829 |

Succeeded by: Enos T. Throop |

| Preceded by: Henry Clay |

United States Secretary of State March 28, 1829 – May 23, 1831 |

Succeeded by: Edward Livingston |

| Preceded by: Louis McLane |

U.S. Minister to Britain 1831 – 1832 |

Succeeded by: Aaron Vail (Chargé d'Affaires) |

| Preceded by: John C. Calhoun |

Democratic Party vice presidential candidate U.S. presidential election, 1832 (won) |

Succeeded by: Richard M. Johnson |

| Preceded by: John C. Calhoun |

Vice President of the United States March 4, 1833 – March 3, 1837 |

Succeeded by: Richard M. Johnson |

| Preceded by: Andrew Jackson |

Democratic Party presidential candidate 1836 (won), U.S. presidential election, 1840 (lost) |

Succeeded by: James K. Polk |

| Preceded by: Andrew Jackson |

President of the United States March 4, 1837 – March 3, 1841 |

Succeeded by: William Henry Harrison |

| Preceded by: (none) |

Free Soil Party Presidential candidate U.S. presidential election, 1848 (lost) |

Succeeded by: John P. Hale |

|

|||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 22:44:08 | 33 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Martin_Van_Buren | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF