Declaration Of Independence

From Conservapedia

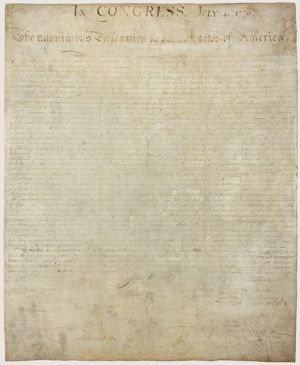

From Conservapedia The Declaration of Independence, unanimously approved by the second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, created a new nation, the "United States of America." Written primarily by Thomas Jefferson, it formally "dissolved the connection" between the thirteen American colonies (which were now using the name the "United Colonies") and Britain. July 4 is still celebrated as the nation's birthday. The document enshrines the basic values of republicanism as the foundation of America, referred to as Americanism; it inspired similar declarations in over a hundred countries.

The Declaration of Independence includes the most influential sentence even written in the English language: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness."

Progressive historians have attempted to re-write history and leave the impression that No taxation without representation was the only reason for American Independence, when there were actually 27 colonial grievances cited against the king.

Contents

- 1 Public opinion

- 2 May 15th resolution

- 3 Writing the Declaration

- 4 Contents

- 5 Immediate impact

- 6 Long-term impact on U.S.

- 7 Declaration under fire by the politically correct

- 8 Global impact

- 9 The physical document

- 10 Full text of the Declaration of Independence

- 11 See also

- 12 Further reading

- 13 Bibliography

- 14 External links

Public opinion[edit]

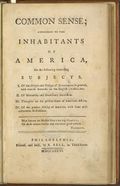

Sentiment for independence was crystallized by Common Sense, the astonishingly successful pamphlet by Thomas Paine. It sold over 150,000 copies in spring 1776; copies were passed from hand to hand and read aloud at taverns in every colony. General George Washington was especially impressed and he had it read aloud to his soldiers. Paine's forceful argument convinced the majority that the Empire was a dead weight on American aspirations, and the time was now to become independent. The Loyalists were left almost speechless. Support for the King, which had been fast dwindling away, evaporated after Americans digested Paine's philippic. Not only was liberty at risk under monarchy, Paine said, but so was peace, as monarchs had little else to do but lay "the world in blood and ashes." His key argument was an attack on the possibility of reconciliation.

Paine convinced his readers that independence was more likely to bring peace and prosperity than continued subservience to the empire. But Paine drove ahead adding a millennial quality to the colonists' struggle. This was not a revolt over taxation. The survival of liberty and republicanism was at stake, he argued and if the American Revolution succeeded, generations yet unborn would owe a debt of gratitude to their forebearers who struggled to defend—-and expand-—freedom. Paine foresaw an America that would become "an asylum for mankind." Not only would America offer refuge to the world's oppressed, but like a shining beacon, revolutionary America would herald "the birth-day of a new world," the beginning of an epoch in which humankind across the earth could "begin the world over again."[1]

May 15th resolution[edit]

On May 15, John Adams wrote a preamble stating that because of the king's continued efforts to reject all efforts at reconciliation, independence from the crown was inevitable.[2]

Writing the Declaration[edit]

The "Declaration Committee," consisted of five people: Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Robert R. Livingston of New York, and John Adams of Massachusetts. It was appointed by Congress on June 11, 1776, to draft a declaration in anticipation of an expected vote in favor of American independence, which occurred on July 2.[3]

At this point the British had been driven entirely from the United Colonies, and independence became increasingly a reality.

Jefferson's role[edit]

As delegates to the Continental Congress Jefferson and John Adams took the lead in pushing for independence. On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee of the Virginia delegation authored the Lee Resolution, proposing independence. Congress appointed a committee of five men to draw up a suitable public Declaration. Shortly after the committee met, Adams and Jefferson were regarded as the two best to do the bulk of the drafting of the document.[4] Adams, however, deferred to Jefferson, on the grounds of three very shrewd reasonings:

"Reason first, you are a Virginian, and a Virginian ought to appear at the head of this business. Reason second, I am obnoxious, suspected, and unpopular. You are very much otherwise. Reason third, you can write ten times better than I can"(Jefferson's authorship was largely unknown before 1800.) He incorporated ideas and phrases from many sources to arrive at a consensus statement that all patriots could agree upon.

Early drafts exist dating to June 1776.[5] Jefferson's colleagues Benjamin Franklin and Adams made small changes in his draft text and Congress made more. The finished document, which both declared independence and proclaimed a philosophy of government, was singly and peculiarly Jefferson's.[6]

Virginia role[edit]

For a more detailed treatment, see Virginia Declaration of Rights.

The opening philosophical section is closely based on Virginia's "Declaration of Rights," a notable summary of current revolutionary philosophy, written by George Mason and adopted in June 1776.[7] Mason wrote:

- That all men are by nature equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.

Jefferson rewrote it:

- We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.--That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

First Draught[edit]

The first draught (they spelled "draft" differently at the time)[8] of the Declaration is somewhat longer and contains more content than the final version that was accepted by all of the colonies. The most glaring difference is a reference to the efforts of the colony of Virginia to rid itself of the practice of slavery.[9] The removal of these sections was by the request of only two states: Georgia and South Carolina.[10]

In the section which highlights slavery, Jefferson takes on a mocking as well as angry tone, using bold text and capitalized lettering to make his point. In one instance, Jefferson mocks the King as a "Christian" who at the same time has no problem enslaving other human beings.(This is not a Christian thing to do) In another instance, Jefferson highlights how the King took a decided stance against any efforts by Virginia to end the practice. Jefferson would have been particularly offended by this, as his first act in the House of Burgesses was a bill to abolish the slave trade. The bill failed by only one vote.[11]

Contents[edit]

Jefferson himself did not believe in absolute human equality, and, though he had no fears of revolution, he preferred that the "social compact" be renewed by periodical, peaceful revisions. That government should be based on popular consent and secure the "inalienable" rights of man, among which he included the pursuit of happiness rather than property, that it should be a means to human well-being and not an end in itself, he steadfastly believed. He gave here a matchless expression of his faith.

The charges against King George III, who is singled out because the patriots denied all claims of parliamentary authority, represent an improved version of charges that Jefferson wrote for the preamble of the Virginia constitution of 1776. Relentless in their reiteration, they constitute a statement of the specific grievances of the revolting party, powerfully and persuasively presented at the bar of public opinion.

The Declaration is notable for both its clarity and subtlety of expression, and it abounds in the felicities that are characteristic of Jefferson's best prose.[12] More impassioned than any other of his writings, it is eloquent in its sustained elevation of style and remains his noblest literary monument.

The concepts of natural law, of inviolable rights, and of government by consent were drawn from the republican tradition that stretched back to ancient Rome and was neither new nor distinctively American. However it was unprecedented for a nation to declare that it would be governed by these propositions. It was Jefferson's almost religious commitment to these republican propositions that is the key to his entire life. He was more than the author of this statement of the national purpose: he was a living example of its philosophy, accepting its ideals as the controlling principles of his own life. Congress adopted the Declaration on July 4, 1776, which became the birthday of the independent nation.[13]

The Declaration of Independence drew upon Christianity and the Enlightenment English philosopher John Locke. In his famous work "Two Treatises of Government" (1690), Locke declared that all men have the natural (inalienable) rights of "life, liberty and estate (property)." Notably the Declaration of Independence does not emphasize a right to pursue property, however, speaking instead in favor of pursuit of "happiness".

Immediate impact[edit]

Voting in Congress was by states and the Declaration was not unanimous on July 4 but became so a little later. On July 4, the New York delegation could not sign since its instructions to do so did not arrive until July 9. The original title referred to Twelve States, but all thirteen approved it. Several delegates were opposed at first but later signed.

When the Declaration was signed, the 13 colonies now became the 13 states. The new nation created a national army under George Washington, and sent diplomats to secure recognition in Europe. Most successful was Benjamin Franklin, who won support in France and in 1778 secured a treaty of military alliance with France, by which the entire military and naval forces of France joined in the war against Britain. King George III refused to give up and of "his" possessions, so the war dragged on until the final American victory at Yorktown in 1781 caused Parliament to change the government in London and sue for peace.

After the publication of the Declaration, several British rebuttals to it were published. John Lind published the Answer to the Declaration of the American Congress, which was commissioned by the administration of Lord North. John Lind worked together with philosopher Jeremy Bentham in its authorship, in which Bentham wrote a scathing criticism of the concept of Natural Rights: "simple nonsense: natural and imprescriptible rights, rhetorical nonsense, — nonsense upon stilts".[14] Another rebuttal was published by colonial governor Thomas Hutchinson. Both pamphlets mock the concept "all men are equal" noting that America did not free every slave - even though it was Britain who brought all the slaves here in the first place.

Long-term impact on U.S.[edit]

Americans celebrated the Fourth of July and often read the Declaration at that event, but paid little attention to it other days of the year.[15] That changed when Abraham Lincoln in the Gettysburg Address of 1863 stressed its priority over the Constitution. Since then the statement that "all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness" has resounded strongly in the American psyche, though it is not echoed much in other countries.

Declaration under fire by the politically correct[edit]

Former state Representative Barbara Norton, a politically correct Democrat from Shreveport, Louisiana, received national attention in 2016, when she opposed a state bill that would require the teaching of the Declaration of Independence in public schools. Norton called the Declaration "racist" because it applied to Caucasians but not slaves. She argued that if "our children will recite the Declaration, I think it's a little bit unfair."[16]

Global impact[edit]

The Declaration was quickly translated into major languages and immediately sparked serious discussion in Europe and Latin America about the legitimacy of empires. By 1826, fifty years after the drafting, twenty nations already had declarations of independence modeled on it, starting with the Flemish 1790 Manifesto of the Province of Flanders and Haiti's 1804 declaration of independence. In the 20th century, the first wave of independence declarations came after World War I and the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires. The second wave lasted from 1945 to 1993, with the closing down of the Japanese, British, French, Portuguese and other empires.

By the 21st century, over half of the 192 nations of the world have such declarations. Most, according to Armitage (2007), have copied the style and structure of the Declaration. Most important, the Declaration has marked and helped create the "contagion of sovereignty" that has transformed a world of empires into a world of states.[17]

The world was impressed with how colonies broke away from an empire, but it paid little attention to its more controversial metaphysical claims about all men being born equal with certain rights. Translators had great difficulty handling its key concepts. For example, the "unalienable rights" of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness were extremely difficult concepts in China, Japan, and Spain (where Catholic teachings placed true happiness only in the other world). The translators' difficulties with the Declaration also indicate that the document's "truths" about human rights were not nearly so "self-evident" as Jefferson believed. In China and Russia, particularly, the political rights of the individual were clearly not self-evident. Although Americans often enthusiastically championed the benefits of democracy throughout the world, not all nations or peoples appreciated the libertarian and capitalist values enunciated in the declaration. They did, however, appreciate its Republicanism, and most new nations declared independence in order to become republics.[18]

The physical document[edit]

Gustafson (2002) traces the various locations where the Declaration, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights, (known collectively as the Charters of Freedom), were kept until transferred with great ceremony to the National Archives in 1952. The Declaration was moved from one city to another and was at the Patent Office in Washington from 1841 to 1876, among other locations. The Declaration and the Constitution were in the Library of Congress from 1921 to 1952, amid some rivalry with the National Archives as to their proper location. As part of a new conservation effort, the National Archives constructed new encasements to preserve the documents and return them to public display beginning 17 September 2003.[19]

Full text of the Declaration of Independence[edit]

The Declaration of Independence is comprised primarily of five sections: The introduction, the preamble, the indictment of the British Crown, the denunciation of the citizens of Britain for turning a blind eye to the King's mistreatment of the colonists, and the conclusion.[20][21][22]

Proclaims the right of the colonists, upon the basis of their God-given rights, to separate from the abusive king. |

IN CONGRESS, JULY 4, 1776 The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen United States of America When in the Course of human events it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation. |

An expression of timeless truths that transcend all ages and generations. |

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. — That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, — That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shewn that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security. — Such has been the patient sufferance of these Colonies; and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter their former Systems of Government. The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States. To prove this, let Facts be submitted to a candid world. |

Lists the 27 grievous acts which the king has repeatedly committed to injure the liberty of his subjects in the 13 colonies. |

He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good. He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them. He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only. He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their Public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures. He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people. He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected, whereby the Legislative Powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the meantime exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within. He has endeavored to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands. He has obstructed the Administration of Justice by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary Powers. He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries. He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people and eat out their substance. He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures. He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil Power. He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation: For quartering large bodies of armed troops among us: For protecting them, by a mock Trial from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States: For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world: For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent: For depriving us in many cases, of the benefit of Trial by Jury: For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offenses: For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments: For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever. He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us. He has plundered our seas, ravaged our coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people. He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to complete the works of death, desolation, and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & Perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation. He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands. He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions. In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince, whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people. |

Denounces the people of Great Britain for not coming to the aid of the colonists as they were abused by their ruler. |

Nor have We been wanting in attentions to our British brethren. We have warned them from time to time of attempts by their legislature to extend an unwarrantable jurisdiction over us. We have reminded them of the circumstances of our emigration and settlement here. We have appealed to their native justice and magnanimity, and we have conjured them by the ties of our common kindred. to disavow these usurpations, which would inevitably interrupt our connections and correspondence. They too have been deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity. We must, therefore, acquiesce in the necessity, which denounces our Separation, and hold them, as we hold the rest of mankind, Enemies in War, in Peace Friends. |

Asserts their reliance upon God for protection, as they knew the King would pursue a path of war. |

We, therefore, the Representatives of the United States of America, in General Congress, Assembled, appealing to the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions, do, in the Name, and by Authority of the good People of these Colonies, solemnly publish and declare, That these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent States, that they are Absolved from all Allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain, is and ought to be totally dissolved; and that as Free and Independent States, they have full Power to levy War, conclude Peace contract Alliances, establish Commerce, and to do all other Acts and Things which Independent States may of right do. — And for the support of this Declaration, with a firm reliance on the protection of Divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor. |

See also[edit]

Further reading[edit]

- Armitage, David. "The Declaration of Independence in World Context." Magazine of History 2004 18(3): 61–66. Issn: 0882-228x Fulltext: Ebsco

- Armitage, David. "The Declaration of Independence and International Law." William and Mary Quarterly 2002 59(1): 39–64. Issn: 0043–5597 in [History Cooperative]; also online edition

- Armitage, David. The Declaration of Independence: A Global History (2007), 300pp excerpt and text search

- Becker, Carl. The Declaration of Independence: A Study on the History of Political Ideas (1922), online edition

- Ellis, Joseph J., ed. What Did the Declaration Declare? Bedford Books, 1999. 110 pp. online review

- Lossing, Benson J. Lives of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence, 1848

- Maier, Pauline. American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence (1998), 336pp excerpt and text search

- Palmer, Robert R. The Age of the Democratic Revolution: A Political History of Europe and America, 1760-1800 (2 vol 1959–64), influential comparison of European countries online edition of vol 1.

- Wills, Garry. Inventing America: Jefferson's Declaration of Independence (2002) excerpt and text search

Bibliography[edit]

- Bancroft, George. History of the United States of America, from the discovery of the American continent. (1854–78), vol 8 online edition

- Barthelmas, Della Gray. The Signers of the Declaration of Independence: A Biographical and Genealogical Reference. McFarland, 2003. 334 pp

- Becker, Carl. The Declaration of Independence: A Study on the History of Political Ideas (1922), online edition

- Boyd, Julian P. The Declaration of Independence: The Evolution of the Text (1945)

- Dershowitz, Alan. America Declares Independence. 2003; attacks notion that it created a "Christian nation"; online edition

- Detweiler, Philip F. "The Changing Reputation of the Declaration of Independence: The First Fifty Years," William and Mary Quarterly, 3d Ser., 19 (1962), 557–74; in JSTOR

- Dumbauld, Edward. The Declaration of Independence and What It Means Today (1950) online edition

- Eicholz, Hans L. Harmonizing Sentiments: The Declaration of Independence and the Jeffersonian Idea of Self Government (2001) online edition

- Ellis, Joseph J., ed. What Did the Declaration Declare? Bedford Books, 1999. 110 pp. online review

- Gustafson, Milton. "Travels of the Charters of Freedom." Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration 2004 (Special Issue): 8-13. Issn: 0033-1031

- Jayne, Allen. Jefferson's Declaration of Independence: Origins, Philosophy and Theology. (1998). 245 pp. online review

- Koch, Adrienne. Philosophy of Thomas Jefferson. (1943) online edition

- McCullough, David. John Adams (2001), very well written popular biography

- McDonald, Robert M. S. "Thomas Jefferson's Changing Reputation as Author of the Declaration of Independence: The First Fifty Years," Journal of the Early Republic, Vol. 19, No. 2 (Summer, 1999), pp. 169–195 in JSTOR

- Maier, Pauline. American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence (1998), 336pp excerpt and text search

- Malone, Dumas. Jefferson and the Rights of Man. 1951. Pp. 550pp, vol 2 of Malone's standard biography

- Middlekauff, Robert. The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763-1789 (2nd ed 2007) general history of the Revolution excerpt and text search

- Miller, John C. Triumph of Freedom, 1775-1783 (1948), standard scholarly political and military history of the Revolution online edition

- Peterson, Merrill D. Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation: A Biography (1986), long, detailed biography by leading scholar; online edition; also excerpt and text search

- Ritz, Wilfred J. "The Authentication of the Engrossed Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776," Law and History Review, Vol. 4, No. 1. (Spring, 1986), pp. 179–204. in JSTOR

- Wills, Garry. Inventing America: Jefferson's Declaration of Independence (2002) excerpt and text search

International impact[edit]

- Adams, Willi Paul. "German Translations of the American Declaration of Independence." Journal of American History 1999 85(4): 1325–1349. Issn: 0021-8723 Fulltext: in Jstor

- Armitage, David. "The Declaration of Independence and International Law." William and Mary Quarterly 2002 59(1): 39–64. Issn: 0043–5597 in [History Cooperative]; also online edition

- Armitage, David. The Declaration of Independence: A Global History (2007), 300pp excerpt and text search

- Armitage, David. "The Declaration of Independence in World Context." Magazine of History 2004 18(3): 61–66. Issn: 0882-228x Fulltext in Ebsco. Discusses the drafting of the Declaration and the international motivations that inspired it, the global reactions to the document in its first fifty years, and its afterlife as a broad modern statement of individual and collective rights.

- Aruga, Tadashi. "The Declaration of Independence in Japan: Translation and Transplantation, 1854-1997," The Journal of American History, Vol. 85, No. 4 (Mar., 1999), pp. 1409–1431 in JSTOR

- Bolkhovitinov, Nikolai N. "The Declaration of Independence: A View from Russia," The Journal of American History, Vol. 85, No. 4 (Mar., 1999), pp. 1389–1398 in JSTOR

- Bonazzi, Tiziano. "Tradurre/Tradire: The Declaration of Independence in the Italian Context," The Journal of American History, Vol. 85, No. 4 (Mar., 1999), pp. 1350–1361 in JSTOR

- Eoyang, Eugene. "Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Linguistic Parity: Multilingual Perspectives on the Declaration of Independence," The Journal of American History, Vol. 85, No. 4 (Mar., 1999), pp. 1449–1454 in JSTOR

- Kutnik, Jerzy. "The Declaration of Independence in Poland," The Journal of American History, Vol. 85, No. 4 (Mar., 1999), pp. 1385–1388 in JSTOR

- Li, Frank. "East is East and West is West: Did the Twain Ever Meet? The Declaration of Independence in China," The Journal of American History, Vol. 85, No. 4 (Mar., 1999), pp. 1432–1448 in JSTOR

- Marienstras, Elise, and Naomi Wulf. "French Translations and Reception of the Declaration of Independence," The Journal of American History, Vol. 85, No. 4 (Mar., 1999), pp. 1299–1324 in JSTOR

- Oltra, Joaquim. "Jefferson's Declaration of Independence in the Spanish Political Tradition," The Journal of American History, Vol. 85, No. 4 (Mar., 1999), pp. 1370–1379 in JSTOR

- Palmer, Robert R. The Age of the Democratic Revolution: A Political History of Europe and America, 1760-1800 (2 vol 1959–64), influential comparison of European countries online edition of vol 1.

- Thelen, David. "Individual Creativity and the Filters of Language and Culture: Interpreting the Declaration of Independence by Translation," The Journal of American History, Vol. 85, No. 4 (Mar., 1999), pp. 1289–1298 in JSTOR

- Troen, S. Ilan. "The Hebrew Translation of the Declaration of Independence," The Journal of American History, Vol. 85, No. 4 (Mar., 1999), pp. 1380–1384 in JSTOR

- Vlasova, Marina A. "The American Declaration of Independence in Russian: The History of Translation and the Translation of History," The Journal of American History, Vol. 85, No. 4 (Mar., 1999), pp. 1399–1408 in JSTOR

- Zoraida Vazquez, Josefina. "The Mexican Declaration of Independence," The Journal of American History, Vol. 85, No. 4 (Mar., 1999), pp. 1362–1369 in JSTOR

References[edit]

- ↑ John Ferling, Setting the World Ablaze: Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and the American Revolution. (2002) p. 130

- ↑ The United States Declaration of Independence (Revisited)

- ↑ Declaring Independence: Drafting the Documents. Retrieved on 2007-08-04.

- ↑ How to Analyze the Works of John Adams

- ↑ See "Transcription of the Fragment of the Composition Draft of the Declaration of Independence"

- ↑ See "Declaration of Independence"

- ↑ see "The Virginia Declaration of Rights," Final Draft,12 June 1776

- ↑ Jefferson's "original Rough draught" of the Declaration of Independence

- ↑ History of the United States of America: From the Discovery of the Continent, Volume IV, by George Bancroft, page 445

- ↑ Extract from Thomas Jefferson’s Notes of Proceedings in the Continental Congress

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson: Inquiry History for Daring Delvers

- ↑ See Carl Becker, The Declaration of Independence: A Study in the History of Political Ideas (1922) ch. 5, online edition; Garry Wills, Inventing America: Jefferson's Declaration of Independence. (1978); Pauline Maier, American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence. (1997)

- ↑ Peterson, Thomas Jefferson and the New Nation (1975) ch. 2

- ↑ Jeremy Bentham’s Attack on Natural Rights

- ↑ Len Travers, Celebrating the Fourth: Independence Day and the Rites of Nationalism in the Early Republic (1999)

- ↑ State Rep: Declaration of Independence Is Racist. Fox News. Retrieved on September 1, 2020.

- ↑ Historians discount the influence of previous declarations. David Armitage, The Declaration of Independence: A Global History (2007) excerpt and text search

- ↑ Eugene Eoyang, "Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Linguistic Parity: Multilingual Perspectives on the Declaration of Independence." Journal of American History 1999 85(4): 1449-1454.

- ↑ Milton Gustafson, "Travels of the Charters of Freedom." Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration 2002 34(4): 274-284. Issn: 0033-1031

- ↑ The Declaration of Independence

- ↑ Our Declaration: A Reading of the Declaration of Independence in Defense of Equality

- ↑ American Rhetoric: Context and Criticism

- ↑ President Woodrow Wilson referred to the preface of the document as something you should overlook.

External links[edit]

- Jefferson and the Declaration

- Library of Congress site on the Declaration's drafting

- Transcript of Jefferson's "Rough Draft" of the Declaration

- Publishing the Declaration of Independence, June 24, 2005 webcast by Robin Shields at the Library of Congress.

- Declaration of Independence of the United States of America, Audiobook at LibriVox

- Original Rough Draught of the Declaration of Independence, Audiobook at LibriVox

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Categories: [United States History] [American Revolution] [American State Papers] [Republicanism]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/18/2023 10:22:56 | 147 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Declaration_of_Independence | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF