Benjamin Franklin

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia | Founding Fathers | |

|---|---|

| |

| Benjamin Franklin | |

| State | Pennsylvania |

| Religion | Christian- Episcopalian [1] |

| Founding Documents | Declaration of Independence, United States Constitution |

Benjamin Franklin (January 17, 1706, Boston - April 17, 1790 Philadelphia), was an American polymath, printer, inventor, statesman, chess enthusiast, and one of the most prominent scientists in the world of the Enlightenment, famed for his discoveries in electricity. He was widely admired in France in addition to the United States.

Franklin's financial success, which he described in his most popular work, The Way to Wealth (1758), embodied the American Dream. His wealth was due in part to his obtaining the right to print Pennsylvania’s paper currency, based on his writing A Modest Enquiry into the Nature and Necessity of a Paper Currency (1729). Later he became the printer of currency for New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland. He also made money as the publisher of the Pennsylvania Gazette, starting in 1729 and known as the finest of all the colonial newspapers.

He was known as "the First American" because his efforts were critical to the formation of a new nation, the success of the American Revolution and the unification of the 13 colonies into the United States of America. Serving as the American minister to France, he secured decisive military and financial support for the Revolution, while asserting the values of democracy and republicanism. He assisted Thomas Jefferson in writing the Declaration of Independence in 1776 and helped legitimize the U.S. Constitution in 1787. His effective diplomacy, creative nationalism, promotion of civic virtue and devotion to republicanism earned him the top tier as a Founding Father.

Contents

- 1 Early life

- 2 Philadelphia Printer

- 3 National communications network

- 4 Marriage

- 5 Civic leader

- 6 Science and invention

- 7 Albany Plan of Union 1754

- 8 Politician

- 9 Colonial agent in London

- 10 Ambassador

- 11 Building a stronger nation

- 12 Slavery

- 13 Death

- 14 Religious Beliefs

- 15 Fame

- 16 Autobiography

- 17 Quotes

- 18 Basic readings

- 19 Detailed Bibliography

- 20 See Also

- 21 References and Notes

- 22 External links

Early life[edit]

Franklin was born on January 17, 1706 in Boston, Massachusetts into a Puritan family. His father was Josiah Franklin, a soap and candle maker, who was married twice and had 17 children. Benjamin briefly attended the very good South Grammar School (affiliated with the Boston Latin School), then at age 10 was pulled out by his father. He was apprenticed at age 12 to his brother James Franklin (1697-1735), one of the first American printers. James published New England Courant and it became Ben's first public forum for his essays, written under the pseudonym "Silence Dogood." Ben, pretending to be a widow, wrote 14 essays in 1722. The essays drew the anger of the local authorities, who prohibited James from publishing it, citing that it mocked religion. Ben, now aged 17, was under legal obligation to his brother but broke with him, and ran away to Philadelphia on his own. Franklin visited his many relatives in Boston in 1733 and reconciled with his brother, and when James died at the age of 38, Ben helped his widow and took charge of James' oldest son.

Philadelphia Printer[edit]

Franklin found work as a printer in Philadelphia. Pennsylvania governor William Keith was one of his patrons, and he persuaded Franklin to go into business for himself and offered him letters of credit in London to purchase equipment. When he arrived in London in December 1724, he learned that Keith's letters of credit were useless. Franklin stayed in London, working in the local print shops. In 1726, he returned to Philadelphia and again worked in print shops. In 1728, Franklin partnered with Hugh Meredith to opened their own print shop. Franklin soon bought out Meredith and in 1730 began publishing The Pennsylvania Gazette newspaper, which he bought from his former employer, Samuel Keimer. Besides the newspaper and almanac, he was a job printer and churned out pamphlets, religious tracts, playbills, tickets, advertisements, legal forms, soap wrappers, election notices, currency, carrier addresses, government documents, book labels, school books such as The New England Primer, and other ephemeral items. In his leisure moments he taught himself to read French, Spanish, Italian, and Latin.

Almanack[edit]

For a more detailed treatment, see Poor Richard's Almanack.

In late 1732, he began writing and publishing Poor Richard's Almanack, under the guise of "Poor Richard Saunders" and his wife, Bridget, both fictional characters. The almanack provided useful information on the seasons while enlightening the reader with witty short sayings. Franklin had a knack for rewording and improving old proverbs in a wittier manner. The almanac appeared annually from 1732 to 1758, selling over 250,000 copies.[2]

National communications network[edit]

One long-term project was creating a network of printers, especially using his own apprentices who would move to other cities to establish themselves. The network of allied printer-publishers extended from New England to the West Indies and lasted from 1729 to the 1790s. It composed his relatives and business associates. It financed printers, played a vital role in developing American journalism, and influenced American morals and ethics by widely disseminating Franklin's ideology of virtue.

Upon finding apprentices whose diligence, skill, and character impressed him, Franklin would make them partners, often setting them up in printing businesses of their own. Subsequently, he would use them to expand his business associations, and as deputy postmaster-general for North America he would set up his associates as postmasters in their local areas. Postmasters were the first to receive news and could communicate it quickly to Franklin through their free use of the postal system. By building and using his communications network Franklin was able to both keep abreast of important developments in the colonies and build a network of supporters and admirers who influenced public opinion in their own cities. As the revolutionary era began, Franklin opposed colonial independence from Britain. Network infighting ensued, pitting Loyalist printers Thomas Wharton and Joseph Galloway against pro-independence publisher William Goddard, who created a private system to deliver his papers that became a model for the US Postal Service. The Continental Congress later appointed Franklin postmaster general, and he, not Goddard, received credit for America's postal system. In 1768, reacting to the Stamp and Townshend acts, Franklin became an activist in the Patriot cause. Many network printers, such as David Hall and James Holt, followed suit, as the colonists polarized between Patriots and Loyalists. As revolt approached, network newspapers became influential foes of Britain. War, turmoil, and Franklin's diplomatic absence while in France caused the network eventually to dissolve, and be replaced by networks of party newspapers.[3]

Marriage[edit]

In September 1730, Franklin entered a common law marriage with Deborah Read. No legal ceremony was possible because Deborah was still legally married; her husband had deserted to avoid paying a debt. Around this time, Franklin fathered an illegitimate son by an unknown woman; William Franklin was raised in his new household. In 1732, his first son with Deborah, Francis died of smallpox at the age of 4, leading Franklin to become an advocate of vaccinations. Sarah Franklin, who went by Sally, was born 11 years later in 1743.

Civic leader[edit]

Franklin became Philadelphia's leading citizen, founding and leading many civic organizations. He was the founder of the American tradition of boosterism, as well as a systematic thinker who analyzed urban problems in the context of rapid population growth. Franklin's understanding of and solution for the urban problems of a growing Philadelphia shaped his later ideas about city-country relationships and his pessimism regarding the future of the United States. Beginning in the 1730s, Franklin actively and publicly addressed such issues as the link between the environment and disease, fire prevention, pollution from tanneries, and restoring the water system in the center of the city (called the Dock) through various engineering projects. Franklin helped improve fire safety and waste handling by mid-century, but manufacturing interests could not be controlled. Franklin believed America would eventually exhaust its vast supply of open, unpopulated land and become increasingly urbanized and demographically imbalanced, thereby making Philadelphia's problems the nation's.[4]

After 1727 Franklin typically operated through "the Junto", an informal club comprising friends, civil leaders and fellow tradesmen. He established America's first subscription library, the Library Company of Philadelphia, in 1731. In 1736, he organized the first volunteer fire department, the Union Fire Company. In 1743, he expanded the idea of the Junto to all of the colonies by organizing the American Philosophical Society. He helped fund the first hospital and planned a professional police force.

Moral reform[edit]

During the 1730s Franklin made a determined effort to use the emerging power of his press to clean up both private character and public space by writing against the excesses of drink, alehouses, fairs, gambling, and other idle pursuits. Franklin's focus on the body and its potential excess is reflective of a transformation in body image and self-image that was part of a broader range of religious, economic, and political transformations that emerged in the 18th century. All were part of a challenge to the traditional authority of church and state; the growth of commerce, the market, and the print public sphere; and the proliferation of a political ideology that presaged the Declaration of Independence. In his Autobiography (1771) Franklin utilized the body and its "inclinations" to drive his narrative. In contrast to Thomas Jefferson, who appealed to abstract human rights, and John Adams, who invoked historical precedent and English canon law, Franklin portrayed the Revolution as an ongoing struggle between inclination and reason.[5]

Franklin did not derive his ideas on ethics and virtue from Puritan thought. The orthodox Puritans stressed the concept of a "double calling," one which distinguishes between an outward calling and an inward one. For the Puritan, the inward calling - through which man is justified by God's grace - took precedence over the outward calling - man's commitment to the world. Cotton Mather's "Bonifacius," which Franklin cites as an influence in the development of his own philosophy, maintains this distinction. Franklin's commitment is to the outward calling. He rejects the central doctrines of Puritanism: Providence, Election, and Original Sin. Franklin actually retained few Puritan ideals.[6]

Franklin's moral theories stemmed from a commonly held concept among 18th century Enlightenment philosophers: that the development of habit can be used for achieving behavioral change. Franklin's approach to the gaining of moral progress was neopagan rather than Christian in its orientation. It stressed the gradual modification of the person's observable actions instead of an emphasis on internal spiritual change. In essence, Franklin's attitude toward habit and moral improvement was almost identical to that later espoused by John Stuart Mill and the utilitarian and associationist schools of philosophy.[7]

Library[edit]

Franklin was the main organizer of the Library Company of Philadelphia, founded in 1731 by middle class "artificers," (craftsmen, like printers, and owners of small businesses). They sought to improve their condition and status through self-education. The library reflected Franklin's belief that reading could change expectations and positions in society. The books at the library were extremely important in Franklin's intellectual development, and his experience there strengthened his beliefs about education. Through the library, members pursued many interests and became involved in natural science through Peter Collinson of London, who acted as its book agent. Nonmembers of both sexes also used the library.[8]

Education[edit]

Franklin's 1749 "Proposals for the Education of Youth in Pensilvania," in which he proposes the formation of an academy and discusses its basically secular curriculum. Religion is to be taught under the rubric of history:

- "History will also afford frequent Opportunities of showing the Necessity of a Publick Religion, from its Usefulness to the Publick; the advantage of a Religious Character among private Persons; the Mischiefs of Superstition, &c. and the Excellency of the CHRISTIAN RELIGION above all others, ancient and modern."

Not a college man, Franklin proposed educational changes that broke decisively with many traditional educational practices of his day. His proposals reflect his own view of the Enlightenment and its perception of the human mind. He helped establish of the "College of Philadelphia" (now the University of Pennsylvania). Unlike Harvard and Yale it was nonsectarian and did not primarily train clergy. Instead it educated students for careers in the professions and business and for public service. It established America's first modern liberal arts curriculum."[9]

Militia[edit]

Franklin helped create the Pennsylvania Militia, independent of the colonial government. The repeated French and Indian Wars were a threat to the frontier, as the French based in Canada organized and armed Indians who raided the frontier settlements. The government was controlled by the Penn family and the Quakers, who refused to organize any military defense. In November 1747, Franklin wrote Plain Truth advocating the creation of a defense force, since the government would not do so. The pamphlet was enthusiastically received and Franklin organized the "Association" in 1747 to defend against attacks on settlements along the Delaware River. It was the first volunteer militia in Pennsylvania. By the end of 1747 ten volunteer regiments, composed of 124 volunteer companies (designed to have 50-100 men each), had been raised. But the militia was organized only after long debate, much of which involved biblical comparisons and religious justifications from both supporters (including Franklin) and opponents of military preparedness. The debate foreshadowed the ultimate demise of Quaker rule in Pennsylvania, since the Quaker legislators realized their refusal to defend the colony meant they had to resign office.[10]

Opposes multiculturalism[edit]

Franklin had a vision of an ethnically homogeneous America, and so he had negative views on the large and expanding German community in Pennsylvania (usually called the "Pennsylvania Dutch.") Franklin's first contacts with the Pennsylvania Germans concerned business. In 1731 he printed two books in German for German Baptists; he also printed into pamphlet form a letter from Conrad Weiser, an Indian negotiator, to Christopher Sauer, a German-language publisher. However, in from the late 1740s into the 1750s, Franklin believed that the Germans could not be assimilated into Englishmen and thus would always be aliens. He disliked the failure of the Germans to assimilate—they had their own language, religion and customs, and showed no interest in becoming like Englishmen or in joining the militia. In "Observations on the Increase of Mankind" (1751), Franklin expressed his opposition toward German immigrants, whom he ridiculed:

- "why should the Palatine Boors be suffered to swarm into our Settlements and, by herding together, establish their Language and Manners, to the Exclusion of ours? Why should Pennsylvania, founded by the English, become a Colony of Aliens, who will shortly be so numerous as to Germanize us instead of our Angli-fying them .. .?"

Despite Franklin's fears, German settlers helped secure the colony's borders against France's Indian supporters during the French and Indian War. Franklin's 1751 remarks came back to haunt him during the 1764 election to determine whether Pennsylvania would remain a proprietary colony or become a royal one (as Franklin advocated) when Franklin's opponents used his comments about the German colonists to defeat his position. Franklin kept silent about the Germans. He was pleased that the Reformed and Lutheran Germans supported the French and Indian War (1757–63) and, even more important, the American Revolution (1775-1783), even as the numerous German pacifist sects like the Dunkers, Amish and Mennonites remained neutral. Franklin and the Germans finally were reconciled in 1787 when Franklin College (now Franklin and Marshall College), was established to promote an better knowledge of the German and English languages, and was named in his honor by the Germans.[11]

In response to British conquest of French-speaking Quebec in 1759, he wrote "The Canada Pamphlet." It stands as one of the most complex and sophisticated pieces of pre-Revolutionary American thought. In it, Franklin entertained ideas of a homogeneous American population in manners, language, and religion as a reaction against ethnic and political warfare within Europe. Drawing on the ideas of Thomas Hobbes, David Hume, and Baruch Spinoza, Franklin believed that political and ethnic relations were exclusively dominated by power, leaving no room for multiculturalism in America, preferring instead the implementation of the British Crown model to foster internal peace in the colonies. Having a reputation as anti-German hurt Franklin politically, and he dropped the nativism after 1765.[12]

Demography[edit]

In 1751 Franklin wrote "Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind, Peopling of Countries, Etc." in which he both anticipated the Malthusian theory of population growth and quite accurately predicted the rate of American population increase for the following century and a half. He showed that the American population doubled every 25 years, while Europe and Asia were static or grew very slowly. England's population supposedly took 360 years to double. There is a paradox in Franklin's treatment of population. He maintained that the tendency of populations to expand until checked by the lack of subsistence was a cause of European miseries, yet he advocated rapid population growth for the American colonies. When his population theory is highlighted, he appears as a Malthusian pessimist; when his population values are highlighted, he appears as an ardent pro-natalist.[13]

Science and invention[edit]

By age 42, Franklin was wealthy enough to retire from publishing and devote most of his time to his scientific pursuits, keeping in touch with the leading scientists in Britain and the Continent. Franklin combined commonsense empiricism, always paying very close attention to details and carefully recording his measurements. At the same time he was insatiably speculative, theoretical, and conjectural.

Franklin's numerous inventions include bifocal glasses,[14] the glass armonica, the flexible catheter, the odometer, and swimming fins.

For is work in science, the Royal Society named Franklin as a Fellow of the Society and received its Copley Medal.[15]

Stove[edit]

In 1742 he invented a device inserted into a fireplace that gave more warmth at a lower fuel cost. His idea, worked out with his friend Robert Grace, consisted of a low stove, equipped with loosely fitting iron plates through which air circulated and was warmed before it entered the room. This "New Pennsylvania Fireplace" avoided drafts, gave more even temperatures throughout the room, and checked loss of heat through the chimney. It was an insert in an already existing hearth, and did not resemble what are now called "Franklin stoves".

Meteorology[edit]

The first contributions to scientific meteorology in America were Franklin's famous experiments regarding lightning, atmospheric electricity, cyclone theory, and ocean circulation, during the years from 1748 to 1775. Franklin designed the experiment that proved that electric sparks created artificially in the laboratory were similar to deadly and destructive lightning bolts, except in magnitude. He proved that there were electric charges in the atmosphere both in cloudy (or thunder) weather and in fine weather. Franklin showed that storms may move progressively "into the wind," by observing that a cyclonic storm with a northeast wind hit Philadelphia a day or so before it hit Boston, which lies to the northeast of Philadelphia. Finally, while crossing the Atlantic between 1746 and 1775, and after discussions with his cousin a ship captain, he reported there is a warm current off the New England coast setting to the northeast—the Gulf Stream—and was able to chart its boundaries fairly accurately.

Discovering electricity[edit]

Franklin's great scientific achievement came in his experiments and theories regarding electricity. He was first intrigued by the concept after meeting Archibald Spencer and witnessing his demonstrations on the creation of static electricity. In 1747, Spencer donated a glass tube and information on generating electricity to the Library Company. Franklin had several of these glass devices made for his experiments. He theorized that electricity was one "fluid." He discovered that when a "positive" charge is created that a "negative" charge is created as well, which became known as the conservation of charge. He also began using Leyden jars, a glass jar with foil on the outside and a conductor such as water or metal on the inside that could be charged with a wire. Franklin determined that the charge was not stored in the conductor, as was previously thought, and was held in the glass.[16] Based on this knowledge, he invented the first electrical battery, which was a series of glass planks that were flanked by metal and wired together.

Franklin began noticing the similar properties of lightning and electrical sparks, which led to his most famous experiment. In 1750, Franklin outlined his proposal in two letters to Peter Collinson, which were published and presented to the Royal Society in London. On May 10, 1752 French scientist Thomas-François D'Alibard successfully performed Franklin's experiment outside of Paris. In June, before word of success had crossed the Atlantic, Franklin performed his kite and key experiment with his son, William, with similar success, which has become a popular part of American folklore.[17] This led to the invention of lightning rods [5], which became widespread in the colonies, as well as Europe, bringing international fame to Franklin almost overnight. In 1753, he received honorary degrees from both Harvard and Yale, and the Royal Society in London awarded him the prestigious Copley Medal.

Franklin is responsible for the nomenclature of "positive" and "negative" charge. He believed he could tell the direction in which electricity traveled by observing sparks. He was wrong; the electrons, which are the particles carrying ordinary electricity, move in the opposite of the direction he thought they did. As a result, when electrons were discovered, according to Franklin's designation they had to be considered as having a negative charge.

Controversies[edit]

There were many rivalries among scientists of the day and Franklin joined in energetically. At every point of Franklin's career, rival scientists disputed his claims to inventions and disagreed with his scientific results. Abbé Nollet, the leader of the French scientific community, reported on experiments which he believed illustrated the shortcomings of Franklin's research on electricity. Nollet maintained that Franklin's lightning rods might ignite fires by attracting electricity. Various European scientists claimed to have thought of Franklin's kite or lightning rod experiments before Franklin. Leading British experimenter William Watson claimed that most of Franklin's ideas had their origins in his own work. Political controversy swirled in England in 1772 when members of the Royal Society debated whether lightning rods should be "points" or "blunts." George III entered the controversy by demanding that blunts should be placed on the royal palace after an official committee, of which Franklin was a member, recommended pointed rods to protect the government powder magazine.[18]

Albany Plan of Union 1754[edit]

While Franklin thought of himself as a loyal subject, and was comfortable with monarchy and aritocracy, he did express an emerging sense of Americanism. In 1753, London promoted Franklin to the position of Deputy Postmaster for the Colonies. The industrious Franklin, who frequently took inspection tours throughout the colonies, revamped the postal system to be more efficient, speeding up delivery times and creating the home delivery system. From visiting the colonies first hand, coupled with the increasing need for frontier defense, Franklin realized that some form of unification of the colonies was necessary. In June 1754, a conference was called by the London Board of Trade to meet in Albany, New York to discuss a more unified defense. He proposed the "Albany Plan of Union", which would have united the colonies under a royal governor, and given the colonies the power to tax themselves. Delegates from several colonies had come together to discuss ways to restore harmonious relations with the Indians but soon found themselves debating Franklin's plan of union, which would have created a unified colonial entity. The Plan was approved by the conference but was unanimously rejected by the colonial assemblies and by London. It was twenty years too soon for the colonies to give up their smug complacency and dependence upon London, rather than each other. In 1754 colonists assumed Britain was a benevolent empire run for the benefit of colonists, but within twenty years realized their error. The Albany plan formed much of the basis for the later American governments established by the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution.

Politician[edit]

In 1751, after serving as a clerk 15 years, Franklin was elected to the Pennsylvania Assembly. He used his new position to advance civic projects such as pushing legislation to maintain and light the streets. One of the primary issues faced by the Assembly was keeping their frontier border safe from Indian attacks orchestrated by the French. There was frequent conflict between the Assembly and the Proprietary leadership of the Penn family. The Penns controlled a vast majority of the lands in Pennsylvania, however, forbid them to be taxed which hampered the Assembly's ability to build an adequate militia. Penn repeatedly fought the Penn family and tried, without success, to have the King take direct control of Pennsylvania.

Colonial agent in London[edit]

In 1757 Franklin was sent to London as the paid representative or lobbyist of the Pennsylvania Assembly to present the colony's side of its controversy with the Penn family, which still owned the colony.

His attempts to persuade this to both Thomas Penn and Parliament failed. Although his mission was over by 1758, Franklin lingered in London for another four years. He enjoyed his time meeting with the local intellectuals and political radicals, and with a touch of regret returned to Philadelphia in 1762. His return to Philadelphia was to be short-lived. In the 1764 elections, Franklin failed to be reelected after a vicious pamphlet war labeled him as anti-German and Scottish, which made up a majority of Pennsylvania's frontier population. He found this to be a blessing in disguise when the Assembly elected to send him back to London to serve as their agent once again. He tried and failed to obtain a recall of the Penn charter. Franklin also became the paid agent in London for Georgia in 1768, for New Jersey in 1769, and for Massachusetts in 1770. These appointments, together with his wide reputation, made Franklin a sort of ambassador extraordinary from the American colonies to Britain.

He remained abroad for eighteen years, not returning to American until 1775. He was invited to join the "Lunar Society" in Birmingham, where he met many intellectuals and leaders of the emerging Industrial Revolution

Stamp Act[edit]

In 1765, he blundered by assuring British politicians that Americans would accept the Stamp Act. He sent a letter to Philadelphia that was made public urging the colonies to simply make the best of it, leading to the misconception that Franklin had something to do with authoring the Stamp Act. News of colonial protest caused him to reverse his position and he helped negotiated trepeal of the hated tax. Afterwards, Franklin regularly opposed British attempts to tax the colonies, arguing that the colonists had the same rights as other British subjects, with the ability to govern and tax through an elected legislature.

In June 1767, Parliament passed the Townshend Act, another tax on colonial goods. Franklin, still loyal to the crown, took a moderate approach - simultaneously criticizing the rash colonials and the rash government. Increasing the great divide was representation in parliament. Americans had none.

Hutchinson letters[edit]

In 1773, Franklin somehow obtained the originals of secret letters written written 1767-1769 by Thomas Hutchinson when he was Chief Justice of Massachusetts to a member of the British government soliciting troops and urging abridgment of American liberties. Franklin sent the letters to friends in the colony, who in turn published them. His intent was to pin the blame on people like Hutchinson for encouraging the unpopular policies, which he hoped would promote a spirit of reconciliation with Britain. He misjudged the situation, however, which led to the Massachusetts Assembly demanding that Parliament remove Hutchinson from his governorship. London by now had lost all patience with the American colonies and had embarked on a series of punishments designed to humiliate the Americans and make them stay in their inferior places. London sent more troops to Boston and brought Franklin before the Privy Council where he was viciously humiliated in public on January 29, 1775. He was stripped of his position of postmaster.

Franklin's political roles in London in 1757-62 and 1764-75 reshaped his political views. Although he loved the scientists and intellectuals, he hated the politicians. He came to see Britain as vain and corrupt, and he returned to his native America in 1775 with the hope that in a still-uncorrupted republic virtue might prevail.[19]

Continental Congress[edit]

Franklin arrived back in Philadelphia on May 5, 1775, and the next day was chosen a member of the Second Continental Congress. Fighting had broken out near Boston, and the New England militia had trapped the British army in the city. The Congress became the voice of the Americans, setting up shadow governments in each colony, getting ready for a major revolt. Militia units up and down the 13 colonies began drilling for war.

Franklin, following the lead of John Adams, began preparing for independence. On July 21, 1775, he presented his scheme for the Articles of Confederation, similar to his Albany Plan, which called for a strong central government and a congress with proportional representation. However, few of his ideas were included in the Articles Congress adopted in 1777. The Patriots now controlled every colony, and incited by the clever reasoning of Thomas Paine, realized that their republican values and way of life were incompatible with conytrol by foreign aristocrats in London. As popular sentiment for independence swelled in late spring 1776, Franklin, joined Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingston as a committee to prepare a Declaration of Independence. Jefferson, the best writer, did the drafting, with Franklin offering his editorial commentary. A new nation emerged on July 4, 1776. It had driven out all the British officials. But they returned in force in August, 1776, seized New York City, and offered to negotiate on everything except independence. Patriots demanded independence and refused to negotiate any other terms. Help was needed from France, so in December 1776, Franklin was sent to Paris, along with Silas Deane and Arthur Lee, to secure aid for the new nation.

Along with being on the committee to draft the Declaration of Independence, Franklin also proposed an idea for the national seal. His proposal was to have a picture of the Isaelites crossing the Red Sea and Pharaoh's army being destoyed by the water encircled by the phrase, "Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God."

Franklin had made his illegitimate son William Franklin, the Royal Governor of New Jersey, but he remained loyal to the Crown, and father and son never reconciled.

He understood the risks the Founding Fathers were taking and told them, "We must all hang together, or we shall hang separately."

Ambassador[edit]

Franklin was America's first minister (ambassador) to King Louis XVI in France, where he was instrumental in obtaining military and economic support for the struggle against Britain. Franklin arrived to great fanfare in France. Already well known for his lightning experiment, his flirtatious manner and wit made him a favorite among the courtiers. Franklin systematically mingled with scientists, writers, intellectuals and government officials in Paris. He avoided court costumes and cultivated the image of a rustic American, sometimes wearing a coonskin cap. The French loved every bit of it and his popularity helped in securing recognition, money and armies and navies to fight Britain.

Diplomat[edit]

Franklin proved himself to be a crafty diplomat. By the end of 1777, after the great American victory at Saratoga, the French became confident the Americans were strong enough to prevail. The French favored an alliance with the Americans, but their ally Spain was opposed, fearing that anti-imperial republicanism might emerge ion Spain's many colonies. Franklin played on the traditional hatred between the British and the French, using the press to get his messages across. On February 5, 1778 he officially signed a treaty of alliance with France with the stipulation that the U.S. must have France's approval to negotiate peace with Britain. The American revolution was now a world war, and as the Netherlands and Spain joined France, and the rest remained neutral, Britain was outnumbered on land and sea and had little hope of defeating the Allies.

Franklin and John Adams did not get along. Adams that Franklin was "too old, too infirm, too indolent and dissipated for the discharge of all the important duties of ambassador, board of war, board of treasury, commissary of prisoners...." Adams did admit that the power of Franklin's name and fame made him essential, and historians generally agree Franklin did a very good job.[20] French aid proved to be critical to the Americans success, most notably in the decisive victory at Yorktown in October 1781. The Revolutionary war was now won, but negotiations dragged on until the Peace of Paris was signed on Sept. 3, 1783. Franklin remarked, about this time: "There never was a good war nor a bad peace."

Franklin was the most traditional American diplomat of era in his tendency to approach diplomacy as a search for compromise, his use of diplomacy as a tool for peace, his insistence on working through proper channels, and his adherence to the norms of good manners and civility. He played a central role in the peace negotiations in Paris, and to the amazement of observers at the time—and historians ever since—won highly favorable terms from the British, especially ownership of all the lands east of the Mississippi River (except Florida, which went to France's ally Spain.) Assisted by diplomats John Jay and John Adams, Franklin demonstrated great foresight and diplomatic aplomb in negotiating the treaty. While military victory certainly influenced the outcome, the envoys' tenacity and adroit craftsmanship nonetheless frustrated much of the great power intrigue aimed at blocking united American independence. By 1783, few European diplomats visualized an independent United States. The American emissaries, steeped in revolutionary fervor and confident after military victory, would not settle for less.[21]

Disinherits his son[edit]

In 1789 Franklin disinherited his only living son, William, who had been Franklin's close personal friend and, beginning in the 1750s, his political protégé. Franklin used his contacts in London to have William named royal governor of New Jersey, a lucrative and highly prestigious position. In 1774, when Franklin was fired as head of the American postal system and publicly humiliated at Whitehall, he believed his son would resign as governor to protest his father's treatment. When William failed to do this and even admonished his father to accept his fate and take a comfortable retirement, an irreparable breach was created between father and son, a rift widened by the son's loyalty to the British crown during the Revolutionary War. Although William attempted to reestablish a father-son relationship, Benjamin refused and could never forgive his son for the public nature of the humiliation he felt William had caused him.[22]

Building a stronger nation[edit]

Franklin returned home in September 1785. Like all nationalists he could see that the Articles of Confederation created a government that was too weak to survive in a dangerous world It had no president and no tax base, for example. Franklin's ideas for an American republic provided a reconciliation of classical republicanism and 18th century economic life. Franklin's demographic view put America and Britain in contrast. He criticized the British emphasis on manufacturing for export, and he preferred agriculture as the best source of national wealth. Although favoring self-sufficiency, as a means for a virtuous independence, Franklin recognized the need for encouraging a vigorous foreign commerce (with free trade). Open space and open markets were essential for republicanism to work.[23]

Franklin can be compared favorably with Frederick Jackson Turner as a promoter of the Frontier Thesis, the idea of the significance of the West in the shaping of American character. Franklin used the words frontier and West interchangeably and generally equated both of them with free land. He believed that the West was decisive in producing the phenomenal population growth of the society of his day and its "middle-class agrarianism." His frontier-inspired ideas had a demonstrable effect on public events and contributed to the coming of the American Revolution. Americans eagerly gave wide currency to Franklin's ideas. His political and diplomatic exertions contributed considerably to insure that the West would be a part of the new nation he was helping to create.[24]

In 1787 the Constitutional Convention convened in Philadelphia to write a new Constitution. Franklin, at age 81 the oldest delegate, played an honorific role and his support helped legitimize the project. Other members of the Pennsylvania delegation to the convention were George Clymer, Thomas Fitzsimons, Jared Ingersoll, Thomas Mifflin, Gouverneur Morris, Robert Morris, and James Wilson.

Slavery[edit]

Franklin in the 1750s owned two slaves, whom he eventually freed, and also ran advertisements for slave sales in his Pennsylvania Gazette. As a youth he had been a runaway himself. As a diplomat he supported slavery, but for Franklin slavery was always more of a political than a moral problem. Late in life he reversed directions and supported the abolition of the slave trade (but not slavery itself). When the case of Somerset v Stewart was decided Franklin was happy that Liberty carried the day, but the hypocrisy of emancipation at home and slavery enforced abroad did not escape him. In an article for the London Chronicle, Franklin wrote:[25]

Pharisaical Britain! to pride thyself in setting free a single Slave that happens to land on thy coasts, while thy Merchants in all thy ports are encouraged by thy laws to continue a commerce whereby so many hundreds of thousands are dragged into a slavery that can scarce be said to end with their lives, since it is entailed on their posterity!

Later, he joined the Pennsylvania Abolition Society and became their president in 1787; his was primarily honorific. The Society had hoped he would bring up the issue of slavery at the Constitutional Convention, which he declined to do, realizing that it would be too contentious of an issue. In November 1789, he published his Address to the Public which appealed for the emancipation of slaves and the further education of free blacks.[26]

Death[edit]

In his later years, Franklin suffered from extremely painful afflictions, such as gout, which oftentimes made it difficult for him to stand upright.[27] His physician, Dr. John Jones, wrote that due to how much pain Franklin constantly dealt with, he prescribed him with laudanum,[28] which is a narcotic opioid. In his final days Franklin was bedridden, and Jones reported that when Franklin was not blinded by "his tortures", he read books, was cheerful with people who came to visit him, and he was grateful of "the many blessings he had received from the Supreme Being".[28]

Franklin died on April 17, 1790 at the age of 84 and was buried at Christ Church, Philadelphia. Civic-minded to the end, Franklin's will established a 200-year trust fund for Boston and Philadelphia which was to be used to train and educate young craftsmen. Both cities have held true to Franklin's wishes, providing aid to students and establishing the Franklin Institute of Boston.

Religious Beliefs[edit]

Franklin progressed from a skepticism towards Puritanism as a youth to a strong belief in God and prayers for His intervention. At all times Franklin believed in God, but was unable to define what God meant for his soul; he never joined a church. Like most in Pennsylvania, he respected freedom of religion by others, but also emphasized the importance of religion in maintaining a society; much of his writing was designed to promote moral behavior. Liberals often like to bring up that he stated "lighthouses are more helpful than churches", as if that is some kind of "proof" that Franklin was only a Deist. It is merely liberal deceit. The British political system at the time of the American rebellion was based very firmly on Anglican Protestantism. Laws stated very clearly the monarch had to be a Protestant, and also that they were the head of The Church of England; even Protestants who were not Anglican had to pay for their own priests and build their own churches. Catholics were still denied the vote. To gather enough support among the colonists to successfully achieve independence, their leaders had to offer them something different, and to belittle the Anglican church in particular, so as to undermine the foundation of the British political system that ruled the American colonies. So, Franklin was saying that functional, useful things (such as lighthouses) contributed more to the safety and well-being of the individual than buildings that provided spiritual things (such as churches). It was his clever means of motivation, not some far-reaching personal belief of his.

Young Ben was an avid reader. "From a child I was fond of reading, and all the little money that came into my hands was ever laid out in books. Pleased with the Pilgrim's Progress, my first collection was of John Bunyan's works in separate little volumes. My old favorite author, Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress ... has been translated into most of the languages of Europe, and suppose it has been more generally read than any other book, except perhaps the Bible."

In 1728, the twenty-two-year-old printer wrote "Articles of Belief and Acts of Religion," which Walters (1999) argues is the most crucial text of all Franklin’s religious writings.[29] Franklin embraced a concept that sanctioned the value of different religions. Walters argues this “theistic perspectivism” is the key to understanding Franklin’s religion, for it allowed him to maintain his most basic belief in a divinity as the "First Cause" while also allowing him to understand different religions and sects as different ways to honor and serve the primary creator. Franklin’s lifelong advocacy of religious tolerance and his refusal to dogmatize resulted from his understanding that all religions helped bring the "First Cause" closer to humanity, bridging the immense gulf between Creator and creation.[30]

Franklin left behind the deism of his youth. In a draft autobiography written mostly in 1771, nearly 20 years prior to his death, Franklin described how he came to deism as a teenager. He recalled that his "parents had early given me religious impressions, and brought me through my childhood piously in the Dissenting way. But I was scarce fifteen, when, after doubting by turns of several points, as I found them disputed in the different books I read, I began to doubt of Revelation itself. Some books against Deism fell into my hands; they were said to be the substance of sermons preached at Boyle's Lectures. It happened that they wrought an effect on me quite contrary to what was intended by them; for the arguments of the Deists, which were quoted to be refuted, appeared to me much stronger than the refutations; in short, I soon became a thorough Deist." [31]

Franklin then abandoned his youthful deism in favor of a strong belief in an interventionist God, as reflected by his prayer request during a troubled period of the Constitutional Convention. In a letter dated March 9, 1790, the last letter Franklin ever wrote, he expressed his strong faith in God and the possibility of heaven:

- "Here is my Creed: I believe in one God, Creator of the Universe. That he governs it by Providence. That he ought to be worshipped. That the most acceptable Service we render to him is doing good to his other Children. That the soul of Man is immortal, and will be treated with Justice in another Life respecting its conduct in in this. These I take to be the fundamental Principles of all sound Religion, and I regard them as you do in whatever sect I meet with them.

- "As to Jesus of Nazareth, my Opinion of whom you particularly desire, I think the system of Morals and His Religion, as he left them to us, the best the world ever saw, or is likely to see; but I apprehend it has received various corrupting Changes, and I have, with most of the present Dissenters in England, some doubt as to his Divinity; tho' it is a question I need not dogmatize upon, having never studied it, and think it needless to busy myself with it now, when I expect soon an Opportunity of knowing the Truth with less Trouble. I see no harm in its being believed, if that belief has the good Consequence, as probably it has, of making his Doctrines more respected and better observed; especially as I do not perceive, that the Supreme takes it amiss, by distinguishing the Unbelievers in his Government of the world with any peculiar Marks of his Displeasure." [32]

Whitefield[edit]

Franklin admired George Whitefield, who first visited the colonies in 1738 and played a major role in the First Great Awakening. Franklin saw Whitefield as a fellow intellectual, but thought Whitefield's plan to run an orphanage in Georgia would lose money. Franklin published several of Whitefield's tract. He was intrigued and himself moved by Whitefield's ability to preach and speak with clarity and enthusiasm to crowds ranging in the thousands. Franklin was an ecumenist and approved of Whitefield's ability to appeal to members of many denominations. Franklin was not moved by the Methodist evangelist's revivals, but did conclude that religiosity was a good thing for other people, so at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, he proposed a prayer for divine intervention to aid the troubled proceedings. After one of Whitefield's sermons, Franklin noted the:

- "wonderful...change soon made in the manners of our inhabitants. From being thoughtless or indifferent about religion, it seem'd as if all the world were growing religious, so that one could not walk thro' the town in an evening without hearing psalms sung in different families of every street."[33]

A lifelong close friendship developed between the revivalist preacher and the worldly, secular humanist. Looking beyond their public images, one finds a common charity, humility, and ethical sense embedded in the character of each man. True loyalty based on genuine affection coupled with a high value placed on friendship helped their association grow even stronger over time.

Fame[edit]

By 1776 Franklin was the most famous American in the world. He was one of the most prominent of the Founding Fathers, early political figures and statesmen of the United States.

In the years immediately following his death, Franklin's reputation fell upon evil days. His political enemies, as well as Federalist Party, journalists systematically emphasized the less attractive aspects of his character and minimized his achievements. The calumny was repeated until the 1850s, when the first real attempts were made to paint a broader portrait of this many-sided man. Franklin's "rags to riches" career had a natural attraction in the go-getter mood of the Gilded Age and he became the patron saint of "getting on," a role that he has not yet lost. The xenophobia of the period also affected the image of Franklin in that his prudential philosophy appeared less an expression of selfishness than a means of achievement expressive of the best in the American national character. The late 19th century also saw the beginning of real Franklin scholarship.[34]

Franklin is one of the few non-presidents whose likeness appears on U.S. currency. Franklin graces the $100 bill while Alexander Hamilton appears on the $10 bill.

In 1933, Isamu Noguchi (1904–88) designed a monument to Franklin. For years, the project languished. It finally came to fruition in Philadelphia in 1984 as “Bolt of Lightning . . . Memorial to Ben Franklin.”

Franklin was highly regarded throughout Europe as a leader in science and diplomacy, and as the representative American and the symbol of the New World's integrity and progress. The intellectual, poltiical and scoial leaders of France viewed Franklin as the epitome of the enlightened legislator, a brilliant inventor, and perceptive economist. He inspired his contemporaries and successive generations of Frenchmen to eulogize him in the arts. His unassailable reputation also encouraged divergent political factions to claim Franklin as a mentor after his death in 1790. Franklin was a figure of the Enlightenment, two countries, and two revolutions and there are still reminders of him in France today.[35]

While most historians have admired Franklin's achievements, British literary critic D. H. Lawrence ridiculed Franklin as excessivelyt middle class. Lawrence spent time in the United States in the 1920s but came to dislike the country. He focused on Franklin as a personification of American culture in two essays. Lawrence's disdain for Franklin was based largely in their different philosophies. Franklin felt man was perfectable, and could excel through hard work, while Lawrence saw man as an imperfect, creative, fragmented being, for whom the body and emotions are central to achieving happiness.[36]

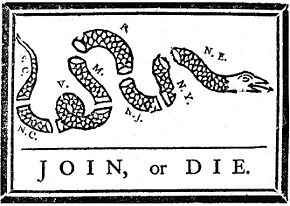

Join or Die[edit]

The famous cartoon entitled "Join, or Die," printed on 9 May 1754 in Franklin's Pennsylvania Gazette, shows a sliced up rattlesnake that forms a map of the colonies. It is impotent unless it joins together, as nature clearly intended. Rattlesnakes—powerful and dangerous creatures that were not found in Britain—were often used to represent America. Georgia, the newest colony, is missing, as is Delaware (then part of Pennsylvania). The cartoon alludes to an old myth that a snake that had been cut into pieces would come back to life if the sections were reassembled before sunset, Franklin based his cartoon on a 17th-century French emblem book by Nicolas Verrien which includes a snake divided into two parts with the motto: 'Se rejoindre ou mourir' ('Join or die').

While the idea behind the illustration was Franklin's, historians have not discovered who did the actual engraving. In form the illustration follows the plan of an emblem book illustration, with a motto, a symbolic picture, and an explanatory text; Franklin even referred to it in correspondence as an "emblem." Franklin was responsible for many visual creations, such as cartoons, designs for flags and paper money, emblems and devices. He possessed an extraordinary knowledge of symbols and heraldry. The snake image may be a composite of those found in Mark Catesby's The Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands (1731–43). The iconic image of national unity became widespread in political illustrations concerning the Stamp Act of 1765, the American Revolution, and both the Union and Confederate causes in the American Civil War.[37]

Autobiography[edit]

A year after Franklin's death, his unfinished draft autobiography, entitled "Memoires De La Vie Privee," was published in Paris in March 1791, and portions soon appeared in English. The first complete edition appeares in 1868. It was one of the first and greatest American autobiographies and appears in many editions. Historians have treated the Autobiography as an allegory for the paradigm of American upward social mobility as well as representing the early economic and political success of America. Beyond this basic representativeness, it endorses the economic promise of free enterprise by using Franklin's life experience to advocate the new nation's economic potential and creditworthiness. Franklin aligns his own history with that of the fledgling United States, in effect equating his ability to successfully capitalize on credit with that of the nation. By depicting his own public credibility, Franklin was able to translate his reputation and promise of success into an endorsement of the viability of American life, intertwining self- and national promotion. In sharp contrast to Jefferson's glorification of the yeoman farmer as the carrier of republican virtue, Franklin looked to the cosmopolitan city for the advancement of mankind, as he tells how the youth arrives in the idyllic city of Philadelphia, where adherence to principles of independence, morality, and industry bring him success.[38]

The Autobiography gave an incomplete view of Franklin. The persona that Franklin assumed here was merely another of the several public roles he adopted in his writings and political activities. He believed that personal growth could only be accomplished by surrendering to a public function, and that the public forum should be a community for discourse rather than a marketplace for personal competition and acquisition.

Quotes[edit]

- From a letter in April 1787: "Only a virtuous people are capable of freedom. As nations become corrupt and vicious, they have more need of masters." and "it would end in despotism, as other forms have done before it, when the people shall have become so corrupted as to need despotic government, being incapable of any other."

- "I have lived, Sir, a long time, and the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth - that God Governs in the affairs of men. And if a sparrow cannot fall to the ground without his notice, is it probable that an empire can rise without his aid? We have been assured, Sir, in the sacred writings, that "except the Lord build the House they labour in vain that build it." I firmly believe this; and I also believe that without his concurring aid we shall succeed in this political building no better, than the Builders of Babel: We shall be divided by our little partial local interests; our projects will be confounded, and we ourselves shall become a reproach and bye word down to future ages. And what is worse, mankind may hereafter from this unfortunate instance, despair of establishing Governments by Human wisdom and leave it to chance, war and conquest."[39]

- "A republic . . . if you can keep it."[40]

- "We must hang together, or most assuredly, we will hang separately." [41]

- "Work as if you were to live a hundred years. Pray as if you were to die tomorrow." [42]

- "Words may show a man's wit but actions his meaning." [43]

- "I think the best way of doing good to the poor, is not making them easy in poverty, but leading or driving them out of it." [44]

- "He that is good for making excuses is seldom good for anything else"

- "In fine, we have the most sensible Concern for the poor distressed Inhabitants of the Frontiers. We have taken every Step in our Power, consistent with the just Rights of the Freemen of Pennsylvania, for their Relief, and we have Reason to believe, that in the Midst of their Distresses they themselves do not wish us to go farther. Those who would give up essential Liberty, to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety." - Reply to the Governor, 11 November 1755[45]

- "As for Jesus of Nazareth ... I think the system of Morals and Religion as he left them to us, the best the World ever saw ... but I have ... some Doubts to his Divinity; though' it is a Question I do not dogmatism upon, having never studied it, and think it is needless to busy myself with it now, where I expect soon an Opportunity of knowing the Truth with less Trouble."[46]

- "Half the truth is often a great lie" [47]

- "I have since had the satisfaction to learn, that a disposition to abolish slavery prevails in North America, that many of the Pennsylvanians have set their Slaves at liberty, and that even the Virginia Assembly have petitioned the King for permission to make a law for preventing the importation of more into that Colony."[48]

- Advocating compromise at the Constitutional Convention: "When a broad table is to be made, and the edges (of planks do not fit) the artist takes a little from both, and makes a good joint. In like manner here both sides must part with some of their demands, in order that they may join in some accommodating proposition."[49]

Basic readings[edit]

- Becker, Carl Lotus. "Benjamin Franklin," Dictionary of American Biography (1931) with hot links online

- Brands, Henry. The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin (2000)- excellent long scholarly biography excerpt and text search

- Isaacson, Walter. Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (2004) - good popular biography excerpt and text search

- Ketcham, Ralph. Benjamin Franklin (1966) 228 pp online edition, by short biography by a scholar

- Morgan, Edmund S. Benjamni Franklin (2003) the best short introduction excerpt and text search

- Van Doren, Carl. Benjamin Franklin (1938), standard older biography excerpt and text search

- Wright, Esmond. Franklin of Philadelphia (1986) - excellent scholarly study excerpt and text search

Detailed Bibliography[edit]

Biographies[edit]

- Becker, Carl Lotus. "Benjamin Franklin," Dictionary of American Biography (1931) - vol 3, with hot links online

- Brands, Henry. The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin (2000)- excellent long scholarly biography excerpt and text search

- Isaacson, Walter. Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (2004) - well written popular biography excerpt and text search

- Ketcham, Ralph. Benjamin Franklin (1966) 228 pp online edition

- Morgan, Edmund S. Benjamni Franklin (2003) the best short introduction excerpt and text search

- Van Doren, Carl. Benjamin Franklin (1938), standard older biography excerpt and text search

- Wood, Gordon. The Americanization of Benjamin Franklin (2005), influential intellectual history by leading conservative historian. excerpt and text search

- Wright, Esmond. Franklin of Philadelphia (1986) - excellent scholarly study excerpt and text search

Specialized Scholarly Studies[edit]

- Anderson, Douglas. The Radical Enlightenments of Benjamin Franklin (1997) - fresh look at the intellectual roots of Franklin

- Buxbaum, M.H., ed. Critical Essays on Benjamin Franklin (1987)

- Chaplin, Joyce. The First Scientific American: Benjamin Franklin and the Pursuit of Genius. (2007)

- Cohen, I. Bernard. Benjamin Franklin's Science (1990) - Cohen, the leading specialist, has several books on Franklin's science

- Conner, Paul W. Poor Richard's Politicks (1965) - analyzes Franklin's ideas in terms of the Enlightenment and republicanism

- Dull, Jonathan. A Diplomatic History of the American Revolution (1985)

- Ford, Paul Leicester. The Many-Sided Franklin (1899) online edition - collection of scholarly essays

- Lemay, J. A. Leo, ed. Reappraising Benjamin Franklin: A Bicentennial Perspective (1993) - scholarly essays

- Lemay, J. A. Leo. The Life of Benjamin Franklin the most detailed scholarly biography, with very little interpretation; 3 volumes appeared before the author's death in 2008

- Volume 1: Journalist, 1706-1730 (2005) 568pp excerpt and text search

- Volume 2: Printer and Publisher, 1730-1747 (2005) 664pp; excerpt and text search

- Volume 3: Soldier, Scientist, and Politician, 1748-1757 (2008), 768pp excerpt and text search

- McCoy, Drew R. "Benjamin Franklin's Vision of a Republican Political Economy for America." William and Mary Quarterly 1978 35(4): 607–628. in JSTOR

- Skemp, Sheila L. Benjamin and William Franklin: Father and Son, Patriot and Loyalist (1994)- Ben's son was a leading Loyalist

Primary Sources[edit]

- Franklin, Benjamin. Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, ed. L.W. Labaree et al. (1964) online edition - there are many editions

- Franklin, Benjamin. Franklin: Writings, ed. J.A. Leo Lemay, Library of America (1987) excerpt and text search; complete text online free

- Franklin, Benjamin. Information to Those Who Would Remove to America (1784)

- Labaree, Leonard W., et al., eds., The Papers of Benjamin Franklin 35 vols. to date (1959-2002) - definitive edition, through 1781. This massive collection of BF's writings, and letters to him, is available in print form at large research libraries. the complete text, searchable, is online free from Yale It is most useful for detailed research on very specific topics.

- Yale edition of complete works of Benjamin Franklin

- The Electrical Writings of Benjamin Franklin Collected by Robert A. Morse, 2004.

- Franklin's Last Will & Testament Transcription.

See Also[edit]

References and Notes[edit]

- ↑ http://www.adherents.com/gov/Founding_Fathers_Religion.html

- ↑ William Pencak, "Politics and Ideololgy in Poor Richard's Almanack". Pennsylvania Magazine Ideologyof History and Biography 1992 116(2): 183-211

- ↑ Ralph Frasca, "'The Glorious Publick Virtue so Predominant in Our Rising Country': Benjamin Franklin's Printing Network During the Revolutionary Era." American Journalism 1996 13(1): 21-37. 0882-1127; Frasca, Benjamin Franklin's Printing Network: Disseminating Virtue in Early America (2006) online edition

- ↑ A. Michal McMahon, "'Small Matters': Benjamin Franklin, Philadelphia, and the 'Progress of Cities.'" Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 1992 116(2): 157-182. 0031-4587

- ↑ Betsy Erkkila, "Franklin and the Revolutionary Body." ELH (English Literary History) 2000 67(3): 717-741. in JSTOR

- ↑ Campbell Tatham, "Benjamin Franklin, Cotton Mather and the Outward State." Early American Literature 1972 6(3): 223-233. in JSTOR

- ↑ Norman S. Fiering, "Benjamin Franklin and the Way to Virtue". American Quarterly 1978 30(2): 199-223. in JSTOR

- ↑ George Boudreau, "'Highly Valuable And Extensively Useful': Community and Readership among the Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia Middling Sort." Pennsylvania History 1996 63(3): 302-329.

- ↑ George W. Boudreau, "'Done by a Tradesman': Franklin's Educational Proposals and the Culture Of Eighteenth-Century Pennsylvania." Pennsylvania History 2002 69(4): 524-557. 0031-4528; see online

- ↑ Barbara A. Gannon, "The Lord is a Man of War, The God of Love and Peace: The Association Debate, Philadelphia 1747-1748." Pennsylvania History 1998 65(1): 46-61.

- ↑ John B. Frantz, "Franklin and the Pennsylvania Germans" Pennsylvania History 1998 65(1): 21-34. 0031-4528; Glenn Weaver, "Benjamin Franklin and the Pennsylvania Germans," William and Mary Quarterly Vol. 14, No. 4 (Oct., 1957), pp. 536-559 in JSTOR

- ↑ Alberto Lena, "Benjamin Franklin's 'Canada Pamphlet' or 'The Ravings of a Mad Prophet': Nationalism, Ethnicity and Imperialism." European Journal of American Culture 2001 20(1): 36-49. 1466-0407

- ↑ Dennis Hodgson, "Benjamin Franklin on Population: From Policy to Theory," Population and Development Review, Vol. 17, No. 4 (Dec., 1991), pp. 639-661 in JSTOR; Alfred Owen Aldridge, "Franklin as Demographer," Journal of Economic History, Vol. 9, No. 1 (May, 1949), pp. 25-44 in JSTOR

- ↑ see illustration

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ We now know that the Leyden jar is an early form of the capacitor, that the charge is contained in a layer of the conductor facing the glass and that the glass (the dielectricum) increases the capacitance of the jar (amount of charge that can be held).

- ↑ See [2], [3] and [4]

- ↑ I. Bernard Cohen, "Franklin's Scientist Enemies: Real or Imagined" Pennsylvania History 1998 65(1): 7-20. 0031-4528

- ↑ Esmond Wright, "'The Fine and Noble China Vase, The British Empire': Benjamin Franklin's 'Love-Hate' View of England". Pennsylvania Magazine of History And Biography 1987 111(4): 435-464.

- ↑ Gorodon Wood, The Americanization of Benjamin Franklin (2004) p 192; Stacy Schiff, A Great Improvisation: Franklin, France, and the Birth of America (2005)

- ↑ Richard Morris, The Peacemakers: The Great Powers and American Independence (1965) is the definitive history.

- ↑ Sheila L. Skemp, "Benjamin Franklin, Patriot, and William Franklin, Loyalist." Pennsylvania History 1998 65(1): 35-45.

- ↑ Drew R. McCoy, "Benjamin Franklin's Vision of a Republican Political Economy for America." William and Mary Quarterly 1978 35(4): 607-628. 0043-5597

- ↑ James H. Hutson, "Benjamin Franklin and the West". Western Historical Quarterly 1973 4(4): 425-434. 0043-3810

- ↑ The Sommersett Case and the Slave Trade, 18–20 June 1772

- ↑ David Waldstreicher, Runaway America: Benjamin Franklin, Slavery, and the American Revolution(2004)

- ↑ "Mr. President": George Washington and the Making of the Nation's Highest Office

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Benjamin Franklin: his autobiography

- ↑ for the text see "Articles of Belief and Acts of Religion" by Benjamin Franklin, November 20, 1728

- ↑ Kerry S. Walters, Benjamin Franklin and His Gods, (1999)

- ↑ http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/etcbin/toccer-new2?id=Fra2Aut.sgm&images=images/modeng&data=/texts/english/modeng/parsed&tag=public&part=all The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, p.57

- ↑ http://personal.pitnet.net/primarysources/franklin-stiles.html

- ↑ The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, p.104-108; Samuel J. Rogal, "Toward a Mere Civil Friendship: Benjamin Franklin and George Whitefield." Methodist History 1997 35(4): 233-243. 0026-1238

- ↑ Richard D. Miles, "The American Image of Benjamin Franklin" American Quarterly 1957 9(2): 117-143. in JSTOR

- ↑ J. A. Leith, "Le Culte de Franklin en France avant et pendant la Révolution Française," ["France's Cult of Franklin before and during the French Revolution"]. Annales Historiques de la Révolution Française, 1976 226 48(4): 543-571. 0003-4436

- ↑ Ormond Seavey, "D. H. Lawrence and 'The First Dummy American'." Georgia Review 1985 39(1): 113-128. 0016-8386; D. H. Lawrence, Studies in Classic American Literature (1923), online edition of ch. 2 on Franklin

- ↑ Karen Severud Cook, "Benjamin Franklin and the Snake that would not Die," British Library Journal 1996 22 (1): 88-112. 0305-5167; Mark Bryant, "The First American Political Cartoon," History Today v. 57#12 (December 2007) pp 58+. online edition

- ↑ Jennifer Jordan Baker, "Benjamin Franklin's Autobiography and the Credibility of Personality." Early American Literature 2000 35(3): 274-293. 0012-8163; James L. Machor, "The Urban Idyll of the New Republic: Moral Geography and the Mythic Hero of Franklin's Autobiography." Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 1986 110(2): 219-236.

- ↑ Madison Debates, June 28, Constitutional Convention

- ↑ http://www.whatwouldthefoundersthink.com/a-republic-if-you-can-keep-it

- ↑ Beyond political correctness: social transformation in the United States - Page 49 by Michael S. Cummings

- ↑ The Quotable Franklin USHistory.org

- ↑ The life of Benjamin Franklin - Page 601 by Benjamin Franklin, John Bigelow

- ↑ Memoirs of Benjamin Franklin - Page 430

- ↑ Pennsylvania Assembly: Reply to the Governor, 11 November 1755

- ↑ http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/community/history/20018/benjamin_franklin_and_his_religious_beliefs/1014592

- ↑ Early American Proverbs and Proverbial Phrases by Bartlett Jere Whiting

- ↑ The works of Benjamin Franklin: with notes and a life of the author by J. Sparks

- ↑ 1 The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, 488 (Max Farrand ed., 1911).

External links[edit]

- "Guide to Benjamin Franklin" by Richard Jensen January 2007

- Leo Lemay, ed. "Benjamin Franklin: A Documentary History"

- Works by Benjamin Franklin - text and free audio - LibriVox

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Categories: [Chess Players] [Inventors] [Founding Fathers] [Journalists] [American Revolution] [United States History] [American Authors] [Scientists] [Diplomacy] [Enlightenment] [British Empire] [Featured articles] [United States History Figures] [Conservatives] [Early National U.S.] [Veterans] [Libertarians] [People Associated with Firearms] [American Gun Rights Advocates] [Patriots]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/22/2023 05:27:06 | 115 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Benjamin_Franklin | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF