Sanskrit

From Nwe

From Nwe | Sanskrit संस्कृतम् saṃskṛtam |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation: | [sə̃skɹ̩t̪əm] | |||

| Spoken in: | India, Nepal | |||

| Total speakers: | 49,736 fluent speakers (1991 Indian census) | |||

| Language family: | Indo-European Indo-Iranian Indo-Aryan Sanskrit |

|||

| Writing system: | Devanāgarī and several other Brāhmī-based scripts | |||

| Official status | ||||

| Official language of: | ||||

| Regulated by: | no official regulation | |||

| Language codes | ||||

| ISO 639-1: | sa | |||

| ISO 639-2: | san | |||

| ISO 639-3: | san | |||

|

||||

Sanskrit (संस्कृता वाक् saṃskṛtā vāk, for short संस्कृतम् saṃskṛtam) is an ancient Indo-European classical language of South Asia, a liturgical language of Hinduism and Buddhism primarily, and utilized occasionally in Jainism. It is one of the twenty-two official languages of India, and an ancestor of the modern Indo-Aryan languages. Its position in the cultures of South and Southeast Asia is akin to that of Latin and Greek in Europe and it has evolved into, as well as influenced, many modern languages of the world. It appears in pre-Classical form as Vedic Sanskrit, which was a spoken language for centuries before the Vedas were written down. Around 600 B.C.E., in the classical period of Iron Age Ancient India, Sanskrit began the transition from a primary language to a second language of religion and learning, used by the educated elite. Classical Sanskrit is defined by the the oldest surviving Sanskrit grammar, Pāṇini's Aṣṭādhyāyī ("Eight-Chapter Grammar") dating to around the fifth century B.C.E.

The corpus of Sanskrit literature encompasses a rich tradition of poetry and drama as well as scientific, technical, philosophical and religious texts. Today, Sanskrit continues to be widely used as a ceremonial language in Hindu religious rituals in the forms of hymns and mantras. Spoken Sanskrit is still in use in a few traditional institutions in India, and there are some attempts at revival.

The scope of this article is the Classical Sanskrit language as laid out in the grammar of Panini, around 500 B.C.E.

History

The language name saṃskṛtam is derived from the past participle saṃskṛtaḥ "self-made, self-done" of the verb saṃ(s)kar- "to make self," where saṃ- "with, together, self" and (s)kar- "do, make." In modern usage, the verbal adjective saṃskṛta- has come to mean "cultured." The language referred to as saṃskṛtā vāk "the language of cultured" has by definition always been a "high" language, used for religious and learned discourse and contrasted with the languages spoken by the people. It is also called deva-bhāṣā meaning "language of the gods."

Sanskrit does not belong to the Indo-Iranian sub-family of the Indo-European family of languages. It is part of the Satem group of Indo-European languages, which also includes the Balto-Slavic branch.

When the term arose in India, "Sanskrit" was not thought of as a specific language set apart from other languages, but rather as a particularly refined or perfected manner of speaking. Knowledge of Sanskrit was a marker of social class and educational attainment and the language was taught mainly to members of the higher castes, through close analysis of Sanskrit grammarians such as Pāṇini. Sanskrit, as the learned language of Ancient India, thus existed alongside the Prakrits (vernaculars), which evolved into the modern Indo-Aryan languages (Hindi, Nepali, Assamese, Marathi, Konkani, Urdu, and Bengali).

Vedic Sanskrit

Sanskrit, as defined by Pāṇini, had evolved out of the earlier "Vedic" form. Vedic Sanskrit is the language of the earliest religious texts of India, the Vedas, a large collection of hymns, incantations, and religio-philosophical discussions which are the the shruti texts of Hinduism. It is an archaic form of Sanskrit, an early descendant of Proto-Indo-Iranian, attested during the period between roughly 1700 B.C.E. (early Rigveda) and 600 B.C.E. (Sutra language).[1] It is closely related to Avestan, the oldest preserved Iranian language.

Scholars often distinguish Vedic Sanskrit and Classical or "Paninian" Sanskrit as separate dialects. Vedic Sanskrit differs from Classical Sanskrit to an extent comparable to the difference between Homeric Greek and Classical Greek; they are very similar and only differ in a few points of phonology, vocabulary, and grammar. Vedic Sanskrit had a pitch accent which could even change the meaning of the words, and was still in use in Panini's time, as we can infer by his use of devices to indicate its position. At some latter time, this was replaced by a stress accent limited to the second to fourth syllables from the end. Today, the pitch accent can be heard only in the traditional Vedic chantings. Vedic Sanskrit often allowed two like vowels to come together without merger during Sandhi (composition of words and phrases).

Classical Sanskrit is considered to have descended from Vedic Sanskrit. Modern linguists regard the metrical hymns of the Rigveda Samhita as the earliest, composed by many authors over centuries of oral tradition. The end of the Vedic period is marked by the composition of the Upanishads, which form the concluding part of the Vedic corpus in the traditional compilations. The current hypothesis holds that the Vedic form of Sanskrit survived until the middle of the first millennium B.C.E. Around 600 B.C.E., in the classical period of Iron Age Ancient India, Sanskrit began the transition from a first language to a second language of religion and learning, marking the beginning of the Classical period.

Classical Sanskrit

Classical Sanskrit is defined by the the oldest surviving Sanskrit grammar, Pāṇini's Aṣṭādhyāyī ("Eight-Chapter Grammar") dating to circa the fifth century B.C.E. It is essentially a prescriptive grammar, an authority that defines rather than describes correct Sanskrit, although it contains descriptive parts, mostly to account for Vedic forms that had already passed out of use in Panini's time.

A significant form of post-Vedic Sanskrit is found in the Sanskrit of the Hindu Epics, the Ramayana and Mahabharata. The deviations from Pāṇini in the epics are generally considered to be the result of interference from prakrits, or "innovations"[2] and not pre-Paninean" usages. Traditional Sanskrit scholars call such deviations aarsha (आर्ष), or "of the rishis," the traditional title for the ancient authors. In some contexts there are more "prakritisms" (borrowings from common speech) than in Classical Sanskrit proper. There is also a language called "Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit" by modern scholars, which is actually a prakrit ornamented with Sanskritized elements (see also termination of spoken Sanskrit). According to Tuwari,[3] there were four principal dialects of Sanskrit; paścimottarī (Northwestern, also called Northern or Western), madhyadeśī (Middle Country), pūrvi (Eastern) and dakṣiṇī (Southern, originating in the Classical period). The first three are even attested in the Vedic Brāhmaṇas, of which the first one was regarded as the purest (Kauṣītaki Brāhmaṇa, 7.6).

European scholarship

European scholarship in Sanskrit, begun by Heinrich Roth (1620–1668) and Johann Ernst Hanxleden (1681–1731), is regarded as being responsible for the discovery of the Indo-European language family by Sir William Jones, and played an important role in the development of Western linguistics.

Sir William Jones, speaking to the Asiatic Society in Calcutta (now Kolkata) on February 2, 1786, said:

The Sanskrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and in the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong, indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists.

Phonology

Classical Sanskrit distinguishes about thirty-six phonemes. There is, however, some allophony and the writing systems used for Sanskrit generally indicate this, thus distinguishing forty-eight sounds

The sounds are traditionally listed in the order vowels (Ach), diphthongs (Hal), anusvara and visarga, plosives (Sparśa) and nasals (starting in the back of the mouth and moving forward), and finally the liquids and fricatives, written in IAST as follows (see the tables below for details):

- a ā i ī u ū ṛ ṝ ḷ ḹ ; e ai o au

- ṃ ḥ

- k kh g gh ṅ; c ch j jh ñ; ṭ ṭh ḍ ḍh ṇ; t th d dh n; p ph b bh m

- y r l v; ś ṣ s h

An alternate traditional ordering is that of the Shiva Sutra of Pāṇini.

Vowels

The vowels of Classical Sanskrit with their word-initial Devanagari symbol, diacritical mark with the consonant प् (/p/), pronunciation (of the vowel alone and of /p/+vowel) in IPA, equivalent in IAST and ITRANS and (approximate) equivalents in English are listed below:

| Letter | Diacritical mark with “प्” | Pronunciation | Pronunciation with /p/ | IAST equiv. | ITRANS equiv. | English equivalent (GA unless stated otherwise) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| अ | प | /ɐ/ or /ə/ | /pɐ/ or /pə/ | a | a | short near-open central vowel or schwa: u in bunny or a in about |

| आ | पा | /aː/ | /paː/ | ā | A | long open back unrounded vowel: a in father (RP |

| इ | िप | /i/ | /pi/ | i | i | short close front unrounded vowel: i in fin |

| ई | पी | /iː/ | /piː/ | ī | I | long close front unrounded vowel: ee in feet |

| उ | पु | /u/ | /pu/ | u | u | short close back rounded vowel: oo in foot |

| ऊ | पू | /uː/ | /puː/ | ū | U | long close back rounded vowel: oo in cool |

| ऋ | पृ | /ɻ/ | /pɻ/ | ṛ | R | short retroflex approximant: r in burl |

| ॠ | पॄ | /ɻː/ | /pɻː/ | ṝ | RR | long retroflex approximant r in burl |

| ऌ | पॢ | /ɭ/ | /pɭ/ | ḷ | LR | short retroflex lateral approximant (no English equivalent) |

| ॡ | पॣ | /ɭː/ | /pɭː/ | ḹ | LRR | long retroflex lateral approximant |

| ए | पे | /eː/ | /peː/ | e | e | long close-mid front unrounded vowel: a in bane (some speakers) |

| ऐ | पै | /əi/ | /pəi/ | ai | ai | a long diphthong: i in ice, i in kite (Canadian English) |

| ओ | पो | /oː/ | /poː/ | o | o | long close-mid back rounded vowel: o in bone (some speakers) |

| औ | पौ | /əu/ | /pəu/ | au | au | a long diphthong: Similar to the ou in house (Canadian English) |

The long vowels are pronounced twice as long as their short counterparts. Also, there exists a third, extra-long length for most vowels, called pluti, which is used in various cases, but particularly in the vocative. The pluti is not accepted by all grammarians.

The vowels /e/ and /o/ continue as allophonic variants of Proto-Indo-Iranian /ai/, /au/ and are categorized as diphthongs by Sanskrit grammarians even though they are realized phonetically as simple long vowels. (See above).

Additional points:

- There are some additional signs traditionally listed in tables of the Devanagari script:

- The diacritic ं called anusvāra, (IAST: ṃ). It is used both to indicate the nasalization of the vowel in the syllable ([◌̃] and to represent the sound of a syllabic /n/ or /m/; e.g. पं /pəŋ/.

- The diacritic ः called visarga, represents /əh/ (IAST: ḥ); e.g. पः /pəh/.

- The diacritic ँ called chandrabindu, not traditionally included in Devanagari charts for Sanskrit, is used interchangeably with the anusvāra to indicate nasalization of the vowel, primarily in Vedic notation; for example, पँ /pə̃/.

- If a lone consonant needs to be written without any following vowel, it is given a halanta/virāma diacritic below (प्).

- The vowel /aː/ in Sanskrit is realized as being more central and less back than the closest English approximation, which is /ɑː/. But the grammarians have classified it as a back vowel.

- The ancient Sanskrit grammarians classified the vowel system as velars, retroflexes, palatals and plosives rather than as back, central and front vowels. Hence ए and ओ are classified respectively as palato-velar (a+i) and labio-velar (a+u) vowels respectively. But the grammarians have classified them as diphthongs and in prosody, each is given two mātrās. This does not necessarily mean that they are proper diphthongs, but neither excludes the possibility that they could have been proper diphthongs at a very ancient stage (see above). These vowels are pronounced as long /eː/ and /oː/ respectively by learned Sanskrit Brahmans and priests of today. Other than the "four" diphthongs, Sanskrit usually disallows any other diphthong—vowels in succession, where they occur, are converted to semivowels according to sandhi rules.

- In the Devanagari script used for Sanskrit, whenever a consonant in a word-ending position is without any virāma (freely standing in the orthography: प as opposed to प्), the neutral vowel schwa (/ə/) is automatically associated with it—this is of course true for the consonant to be in any position in the word. Word-ending schwa is always short. But the IAST a appended to the end of masculine noun words rather confuses the foreigners to pronounce it as /ɑː/—this makes the masculine Sanskrit words sound like feminine words, for example, shiva must be pronounced as /ɕivə/ and not as /ɕivɑː/.

Consonants

IAST and Devanagari notations are given, with approximate IPA values in square brackets.

| Labial Ōshtya |

Labiodental Dantōshtya |

Dental Dantya |

Retroflex Mūrdhanya |

Palatal Tālavya |

Velar Kanthya |

Glottal | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop Sparśa |

Unaspirated Alpaprāna |

p प [p] | b ब [b] | t त [t̪] | d द [d̪] | ṭ ट [ʈ] | ḍ ड [ɖ] | c च [c͡ç] | j ज [ɟ͡ʝ] | k क [k] | g ग [g] | |||

| Aspirated Mahāprāna |

ph फ [pʰ] | bh भ [bʱ] | th थ [t̪ʰ] | dh ध [d̪ʱ] | ṭh ठ [ʈʰ] | ḍh ढ [ɖʱ] | ch छ [c͡çʰ] | jh झ [ɟ͡ʝʱ] | kh ख [kʰ] | gh घ [gʱ] | ||||

| Nasal Anunāsika |

m म [m] | n न [n̪] | ṇ ण [ɳ] | ñ ञ [ɲ] | ṅ ङ [ŋ] | |||||||||

| Semivowel Antastha |

v व [ʋ] | y य [j] | ||||||||||||

| Liquid Drava |

l ल [l] | r र [r] | ||||||||||||

| Fricative Ūshman |

s स [s̪] | ṣ ष [ʂ] | ś श [ɕ] | ḥ ः [h] | h ह [ɦ] | |||||||||

The table below shows the traditional listing of the Sanskrit consonants with the (nearest) equivalents in English/Spanish. Each consonant shown below is deemed to be followed by the neutral vowel schwa (/ə/), and is named in the table as such.

| Unaspirated Voiceless Alpaprāna Śvāsa |

Aspirated Voiceless Mahāprāna Śvāsa |

Unaspirated Voiced Alpaprāna Nāda |

Aspirated Voiced Mahāprāna Nāda |

Nasal Anunāsika Nāda |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Velar Kantya |

क /kə/; English: skip |

ख /kʰə/; English: cat |

ग /gə/; English: game |

घ /gʱə/; somewhat similar to English: doghouse |

ङ /ŋə/; English: ring |

| Palatal Tālavya |

च /cə/; English: exchange |

छ /cʰə/; English: church |

ज /ɟə/; ≈English: jam |

झ /ɟʱə/; somewhat similar to English: hedgehog |

ञ /ɲə/; English: bench |

| Retroflex Mūrdhanya |

ट /ʈə/; No English equivalent |

ठ /ʈʰə/; No English equivalent |

ड /ɖə/; No English equivalent |

ढ /ɖʱə/; No English equivalent |

ण /ɳə/; No English equivalent |

| Apico-Dental Dantya |

त /t̪ə/; Spanish: tomate |

थ /t̪ʰə/; Aspirated /t̪/ |

द /d̪ə/; Spanish: donde |

ध /d̪ʱə/; Aspirated /d̪/ |

न /n̪ə/; English: name |

| Labial Ōshtya |

प /pə/; English: spin |

फ /pʰə/; English: pit |

ब /bə/; English: bone |

भ /bʱə/; somewhat similar to English: clubhouse |

म /mə/; English: mine |

| Palatal Tālavya |

Retroflex Mūrdhanya |

Dental Dantya |

Labial/ Glottal Ōshtya |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approximant Antastha |

य /jə/; English: you |

र /rə/; English: trip (Scottish English) |

ल /l̪ə/; English: love |

व (labio-dental) /ʋə/; English: vase |

| Sibilant/ Fricative Ūshman |

श /ɕə/; English: ship |

ष /ʂə/; Retroflex form of /ʃ/ |

स /s̪ə/; English: same |

ह (glottal) /ɦə/; English behind |

Phonology and Sandhi

The Sanskrit vowels are as discussed in the section above. The long syllabic l (ḹ) is not attested, and is only discussed by grammarians for systematic reasons. Its short counterpart ḷ occurs in a single root only, kḷp "to order, array." Long syllabic r (ṝ) is also quite marginal, occurring in the genitive plural of r-stems (for example, mātṛ "mother" and pitṛ "father" have gen.pl. mātṝṇām and pitṝṇām). i, u, ṛ, ḷ are vocalic allophones of consonantal y, v, r, l. There are thus only 5 invariably vocalic phonemes,

- a, ā, ī, ū, ṝ.

Visarga ḥ ः is an allophone of r and s, and anusvara ṃ, Devanagari ं of any nasal, both in pausa (ie, the nasalized vowel). The exact pronunciation of the three sibilants may vary, but they are distinct phonemes. An aspirated voiced sibilant /zʱ/ was inherited by Indo-Aryan from Proto-Indo-Iranian but lost shortly before the time of the Rigveda (aspirated fricatives are exceedingly rare in any language). The retroflex consonants are somewhat marginal phonemes, often being conditioned by their phonetic environment; they do not continue a PIE series and are often ascribed by some linguists to the substratal influence of Dravidian. The nasal [ɲ] is a conditioned allophone of /n/ (/n/ and /ɳ/ are distinct phonemes—aṇu "minute," "atomic" [nom. sg. neutr. of an adjective] is distinctive from anu "after," "along;" phonologically independent /ŋ/ occurs only marginally, for example, in prāṅ "directed forwards/towards" [nom. sg. masc. of an adjective]). There are thus 31 consonantal or semi-vocalic phonemes, consisting of four/five kinds of stops realized both with or without aspiration and both voiced and voiceless, three nasals, four semi-vowels or liquids, and four fricatives, written in IAST transliteration as follows:

- k, kh, g, gh; c, ch, j, jh; ṭ, ṭh, ḍ, ḍh; t, th, d, dh; p, ph, b, bh; m, n, ṇ; y, r, l, v; ś, ṣ, s, h

or a total of 36 unique Sanskrit phonemes altogether.

The phonological rules to be applied when combining morphemes to a word, and when combining words to a sentence are collectively called sandhi "composition." Texts are written phonetically, with sandhi applied (except for the so-called padapāṭha).

Writing System

Historically, Sanskrit was not associated with any particular script. The emphasis on orality, not textuality, in the Vedic Sanskrit tradition was maintained through the development of early classical Sanskrit literature. When Sanskrit was written, the choice of writing system was influenced by the regional scripts of the scribes. As such, virtually all of the major writing systems of South Asia have been used for the production of Sanskrit manuscripts. Since the late nineteenth century, Devanagari has been considered as the de facto writing system for Sanskrit,[4] possibly because of the European practice of printing Sanskrit texts in the script.

Writing came relatively late to India, introduced from the Middle East by traders around the fifth century B.C.E., according to a hypothesis by Rhys Davids. Even after the introduction of writing, oral tradition and memorization of texts remained a prominent feature of Sanskrit literature. In northern India, there are Brahmi inscriptions dating from the third century B.C.E. onwards, the oldest appearing on the famous Prakrit pillar inscriptions of king Ashoka. Roughly contemporary with the Brahmi, the Kharosthi script was used. Later (c. fourth to eighth centuries C.E.) the Gupta script, derived from Brahmi, became prevalent. From around the eighth century, the Sharada script evolved out of the Gupta script, and was mostly displaced in its turn by Devanagari from about the twelfth century, with intermediary stages such as the Siddham script. In Eastern India, the Bengali script and, later, the Oriya script, were used.

In the south where Dravidian languages predominate, scripts used for Sanskrit include Kannada in Kannada and Telugu speaking regions, Telugu in Telugu and Tamil speaking regions, Malayalam and Grantha in Tamil speaking regions.

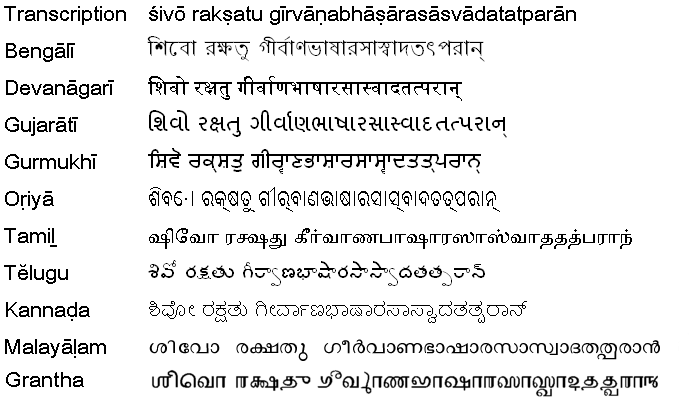

Sanskrit in modern Indian scripts. May Śiva bless those who take delight in the language of the gods. (Kalidasa)

Romanization

Since the late eighteenth century, Sanskrit has been transliterated using the Latin alphabet. The system most commonly used today is the IAST (International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration), which has been the academic standard since 1912. ASCII-based transliteration schemes have evolved due to difficulties representing Sanskrit characters in computer systems. These include Harvard-Kyoto and ITRANS, a lossless transliteration scheme that is used widely on the Internet, especially in Usenet and in email, for considerations of speed of entry as well as rendering issues. With the wide availability of Unicode-aware web browsers, IAST has become common online.

European scholars in the nineteenth century generally preferred Devanagari for the transcription and reproduction of whole texts and lengthy excerpts. However, references to individual words and names in texts composed in European languages were usually represented with Roman transliteration. From the mid twentieth century, textual editions edited by Western scholars have mostly been in romanized transliteration.

Grammar

Grammatical tradition

Sanskrit grammatical tradition (vyākaraṇa, one of the six Vedanga disciplines) began in late Vedic India and culminated in the Aṣṭādhyāyī of Pāṇini, which consists of 3990 sutras (c. fifth century B.C.E.). After a century Pāṇini (around 400 B.C.E.) Kātyāyana composed Vārtikas on Pāninian sũtras. Patañjali, who lived three centuries after Pānini, wrote the Mahābhāṣya, the "Great Commentary" on the Aṣṭādhyāyī and Vārtikas. Because of these three ancient Sanskrit grammarians this grammar is called Trimuni Vyākarana. To understand the meaning of sutras, Jayaditya and Vāmana wrote the commentry named Kāsikā in 600 C.E.. Paninian grammar is based on fourteen Shiva sutras (aphorisms); here the whole Mātrika (alphabet) is abbreviated. This abbreviation is called Pratyāhara.[5]

Verbs

Classification of verbs

Sanskrit has ten classes of verbs divided into in two broad groups: athematic and thematic. The thematic verbs are so called because an a, called the theme vowel, is inserted between the stem and the ending. This serves to make the thematic verbs generally more regular. Exponents used in verb conjugation include prefixes, suffixes, infixes, and reduplication. Every root has (not necessarily all distinct) zero, guṇa, and vṛddhi grades. If V is the vowel of the zero grade, the guṇa-grade vowel is traditionally thought of as a + V, and the vṛddhi-grade vowel as ā + V.

Tense systems

The verbs tenses, which express more distinctions than simply temporal sequence, are organized into four "systems" (as well as gerunds and infinitives, and forms such as intensives/frequentatives, desideratives, causatives, and benedictives derived from more basic forms) based on the different stem forms (derived from verbal roots) used in conjugation. There are four tense systems:

- Present (Present, Imperfect, Imperative, Optative)

- Perfect

- Aorist

- Future (Future, Conditional)

Present system

The present system includes the present and imperfect tenses, the optative and imperative moods, as well as some of the remnant forms of the old subjunctive. The tense stem of the present system is formed in various ways. The numbers are the native grammarians' numbers for these classes.

For athematic verbs, the present tense stem may be formed through

- 2) No modification at all, for example ad from ad "eat."

- 3) Reduplication prefixed to the root, for example juhu from hu "sacrifice."

- 7) Infixion of na or n before the final root consonant (with appropriate sandhi changes), for example rundh or ruṇadh from rudh "obstruct."

- 5) Suffixation of nu (guṇa form no), for example sunu from su "press out."

- 8) Suffixation of u (guṇa form o), for example tanu from tan "stretch." For modern linguistic purposes it is better treated as a subclass of the 5th. tanu derives from tnnu, which is zero-grade for *tannu, because in the Proto-Indo-European language [m] and [n] could be vowels, which in Sanskrit (and Greek) change to [a]. Most members of the 8th class arose this way; kar = "make," "do" was 5th class in Vedic (krnoti = "he makes"), but shifted to the 8th class in Classical Sanskrit (karoti = "he makes")

- 9) Suffixation of nā (zero-grade nī or n), for example krīṇa or krīṇī from krī "buy."

For thematic verbs, the present tense stem may be formed through

- 1) Suffixation of the thematic vowel a with guṇa strengthening, for example, bháva from bhū "be."

- 6) Suffixation of the thematic vowel a with a shift of accent to this vowel, for example tudá from tud "thrust."

- 4) Suffixation of ya, for example dī́vya from div "play."

The tenth class described by native grammarians refers to a process which is derivational in nature, and thus not a true tense-stem formation. It is formed by suffixation of ya with guṇa strengthening and lengthening of the root's last vowel, for example bhāvaya from bhū "be."

Perfect system

The perfect system includes only the perfect tense. The stem is formed with reduplication as with the present system.

The perfect system also produces separate "strong" and "weak" forms of the verb—the strong form is used with the singular active, and the weak form with the rest.

Aorist system

The aorist system includes aorist proper (with past indicative meaning, e.g. abhūḥ "you were") and some of the forms of the ancient injunctive (used almost exclusively with mā in prohibitions, for example, mā bhūḥ "don't be"). The principal distinction of the two is presence/absence of an augment – a- prefixed to the stem. The aorist system stem actually has three different formations: The simple aorist, the reduplicating aorist (semantically related to the causative verb), and the sibilant aorist. The simple aorist is taken directly from the root stem (for example, bhū-: a-bhū-t "he was"). The reduplicating aorist involves reduplication as well as vowel reduction of the stem. The sibilant aorist is formed with the suffixation of s to the stem.

Future system

The future system is formed with the suffixation of sya or iṣya and guṇa.

Verbs: Conjugation

Each verb has a grammatical voice, whether active, passive or middle. There is also an impersonal voice, which can be described as the passive voice of intransitive verbs. Sanskrit verbs have an indicative, an optative and an imperative mood. Older forms of the language had a subjunctive, though this had fallen out of use by the time of Classical Sanskrit.

Basic conjugational endings

Conjugational endings in Sanskrit convey person, number, and voice. Different forms of the endings are used depending on what tense stem and mood they are attached to. Verb stems or the endings themselves may be changed or obscured by sandhi.

| Active | Middle | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Dual | Plural | ||

| Primary | First Person | mi | vás | más | é | váhe | máhe |

| Second Person | si | thás | thá | sé | ā́the | dhvé | |

| Third Person | ti | tás | ánti, áti | té | ā́te | ánte, áte | |

| Secondary | First Person | am | vá | má | í, á | váhi | máhi |

| Second Person | s | tám | tá | thā́s | ā́thām | dhvám | |

| Third Person | t | tā́m | án, ús | tá | ā́tām | ánta, áta, rán | |

| Perfect | First Person | a | vá | má | é | váhe | máhe |

| Second Person | tha | áthus | á | sé | ā́the | dhvé | |

| Third Person | a | átus | ús | é | ā́te | ré | |

| Imperative | First Person | āni | āva | āma | āi | āvahāi | āmahāi |

| Second Person | dhí, hí,— | tám | tá | svá | ā́thām | dhvám | |

| Third Person | tu | tā́m | ántu, átu | tā́m | ā́tām | ántām, átām | |

Primary endings are used with present indicative and future forms. Secondary endings are used with the imperfect, conditional, aorist, and optative. Perfect and imperative endings are used with the perfect and imperative respectively.

Present system conjugation

Conjugation of the present system deals with all forms of the verb utilizing the present tense stem (explained under Tense Stems above). This includes the present tense of all moods, as well as the imperfect indicative.

Athematic inflection

The present system differentiates strong and weak forms of the verb. The strong/weak opposition manifests itself differently depending on the class:

- The root and reduplicating classes (2 & 3) are not modified in the weak forms, and receive guṇa in the strong forms.

- The nasal class (7) is not modified in the weak form, extends the nasal to ná in the strong form.

- The nu-class (5) has nu in the weak form and nó in the strong form.

- The nā-class (9) has nī in the weak form and nā́ in the strong form. nī disappears before vocalic endings.

The present indicative takes primary endings, and the imperfect indicative takes secondary endings. Singular active forms have the accent on the stem and take strong forms, while the other forms have the accent on the endings and take weak forms.

| Active | Middle | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Dual | Plural | ||

| Present | First Person | dvéṣmi | dviṣvás | dviṣmás | dviṣé | dviṣváhe | dviṣmáhe |

| Second Person | dvékṣi | dviṣṭhás | dviṣṭhá | dvikṣé | dviṣā́the | dviḍḍhvé | |

| Third Person | dvéṣṭi | dviṣṭás | dviṣánti | dviṣṭé | dviṣā́te | dviṣáte | |

| Imperfect | First Person | ádveṣam | ádviṣva | ádviṣma | ádviṣi | ádviṣvahi | ádviṣmahi |

| Second Person | ádveṭ | ádviṣṭam | ádvisṭa | ádviṣṭhās | ádviṣāthām | ádviḍḍhvam | |

| Third Person | ádveṭ | ádviṣṭām | ádviṣan | ádviṣṭa | ádviṣātām | ádviṣata | |

The optative takes secondary endings. yā is added to the stem in the active, and ī in the passive.

| Active | Middle | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Dual | Plural | |

| First Person | dviṣyā́m | dviṣyā́va | dviṣyā́ma | dviṣīyá | dviṣīvahi | dviṣīmahi |

| Second Person | dviṣyā́s | dviṣyā́tam | dviṣyā́ta | dviṣīthās | dviṣīyāthām | dviṣīdhvam |

| Third Person | dviṣyā́t | dviṣyā́tām | dviṣyus | dviṣīta | dviṣīyātām | dviṣīran |

The imperative takes imperative endings. Accent is variable and affects vowel quality. Forms which are end-accented trigger guṇa strengthening, and those with stem accent do not have the vowel affected.

| Active | Middle | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Dual | Plural | |

| First Person | dvéṣāṇi | dvéṣāva | dvéṣāma | dvéṣāi | dvéṣāvahāi | dvéṣāmahāi |

| Second Person | dviḍḍhí | dviṣṭám | dviṣṭá | dvikṣvá | dviṣāthām | dviḍḍhvám |

| Third Person | dvéṣṭu | dviṣṭā́m | dviṣántu | dviṣṭā́m | dviṣā́tām | dviṣátām |

Nominal inflection

Sanskrit is a highly inflected language with three grammatical genders (masculine, feminine, neuter) and three numbers (singular, plural, dual). It has eight cases: Nominative, vocative, accusative, instrumental, dative, ablative, genitive, and locative.

The number of actual declensions is debatable. Panini identifies six karakas corresponding to the nominative, accusative, dative, instrumental, locative, and ablative cases. Panini defines them as follows (Ashtadhyayi, I.4.24-54):

- Apadana (lit. "take off"): "(that which is) firm when departure (takes place)." This is the equivalent of the ablative case, which signifies a stationary object from which movement proceeds.

- Sampradana ("bestowal"): "He whom one aims at with the object." This is equivalent to the dative case, which signifies a recipient in an act of giving or similar acts.

- Karana ("instrument") "That which effects most." This is equivalent to the instrumental case.

- Adhikarana ("location"): Or "substratum." This is equivalent to the locative case.

- Karman ("deed/object"): "What the agent seeks most to attain." This is equivalent to the accusative case.

- Karta ("agent"): "He/that which is independent in action." This is equivalent to the nominative case. (On the basis of Scharfe, 1977: 94)

Possessive (Sambandha) and vocative are absent in Panini's grammar.

In this article they are divided into five declensions. The declension to which a noun belongs to is determined largely by form.

Basic noun and adjective declension

The basic scheme of suffixation is given in the table below—valid for almost all nouns and adjectives. However, according to the gender and the ending consonant/vowel of the uninflected word-stem, there are predetermined rules of compulsory sandhi which would then give the final inflected word. The parentheses give the case-terminations for the neuter gender, the rest are for masculine and feminine gender. Both devanagari script and IAST transliterations are given.

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative (Karta) |

-स् -s (-म् -m) |

-औ -au (-ई -ī) |

-अस् -as (-इ -i) |

| Accusative (Karma) |

-अम् -am (-म् -m) |

-औ -au (-ई -ī) |

-अस् -as (-इ -i) |

| Instrumental (Karana) |

-आ -ā | -भ्याम् -bhyām | -भिस् -bhis |

| Dative (Sampradana) |

-ए -e | -भ्याम् -bhyām | -भ्यस् -bhyas |

| Ablative (Apadana) |

-अस् -as | -भ्याम् -bhyām | -भ्यस् -bhyas |

| Genitive (Sambandha) |

-अस् -as | -ओस् -os | -आम् -ām |

| Locative (Adhikarana) |

-इ -i | -ओस् -os | -सु -su |

| Vocative | -स् -s (- -) |

-औ -au (-ई -ī) |

-अस् -as (-इ -i) |

a-stems

A-stems (/ə/ or /aː/) comprise the largest class of nouns. As a rule, nouns belonging to this class, with the uninflected stem ending in short-a (/ə/), are either masculine or neuter. Nouns ending in long-A (/aː/) are almost always feminine. A-stem adjectives take the masculine and neuter in short-a (/ə/), and feminine in long-A (/aː/) in their stems. This class is so big because it also comprises the Proto-Indo-European o-stems.

| Masculine (kāma-) | Neuter (āsya- 'mouth') | Feminine (kānta- 'beloved') | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Dual | Plural | |

| Nominative | kā́mas | kā́māu | kā́mās | āsyàm | āsyè | āsyā̀ni | kāntā | kānte | kāntās |

| Accusative | kā́mam | kā́māu | kā́mān | āsyàm | āsyè | āsyā̀ni | kāntām | kānte | kāntās |

| Instrumental | kā́mena | kā́mābhyām | kā́māis | āsyèna | āsyā̀bhyām | āsyāìs | kāntayā | kāntābhyām | kāntābhis |

| Dative | kā́māya | kā́mābhyām | kā́mebhyas | āsyā̀ya | āsyā̀bhyām | āsyèbhyas | kāntāyai | kāntābhyām | kāntābhyās |

| Ablative | kā́māt | kā́mābhyām | kā́mebhyas | āsyā̀t | āsyā̀bhyām | āsyèbhyas | kāntāyās | kāntābhyām | kāntābhyās |

| Genitive | kā́masya | kā́mayos | kā́mānām | āsyàsya | āsyàyos | āsyā̀nām | kāntāyās | kāntayos | kāntānām |

| Locative | kā́me | kā́mayos | kā́meṣu | āsyè | āsyàyos | āsyèṣu | kāntāyām | kāntayos | kāntāsu |

| Vocative | kā́ma | kā́mau | kā́mās | ā́sya | āsyè | āsyā̀ni | kānte | kānte | kāntās |

i- and u-stems

| Masc. and Fem. (gáti- 'gait') | Neuter (vā́ri- 'water') | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Dual | Plural | |

| Nominative | gátis | gátī | gátayas | vā́ri | vā́riṇī | vā́rīṇi |

| Accusative | gátim | gátī | gátīs | vā́ri | vā́riṇī | vā́rīṇi |

| Instrumental | gátyā | gátibhyām | gátibhis | vā́riṇā | vā́ribhyām | vā́ribhis |

| Dative | gátaye, gátyāi | gátibhyām | gátibhyas | vā́riṇe | vā́ribhyām | vā́ribhyas |

| Ablative | gátes, gátyās | gátibhyām | gátibhyas | vā́riṇas | vā́ribhyām | vā́ribhyas |

| Genitive | gátes, gátyās | gátyos | gátīnām | vā́riṇas | vā́riṇos | vā́riṇām |

| Locative | gátāu, gátyām | gátyos | gátiṣu | vā́riṇi | vā́riṇos | vā́riṣu |

| Vocative | gáte | gátī | gátayas | vā́ri, vā́re | vā́riṇī | vā́rīṇi |

| Masc. and Fem. (śátru- 'enemy') | Neuter (mádhu- 'honey') | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Dual | Plural | |

| Nominative | śátrus | śátrū | śátravas | mádhu | mádhunī | mádhūni |

| Accusative | śátrum | śátrū | śátrūn | mádhu | mádhunī | mádhūni |

| Instrumental | śátruṇā | śátrubhyām | śátrubhis | mádhunā | mádhubhyām | mádhubhis |

| Dative | śátrave | śátrubhyām | śátrubhyas | mádhune | mádhubhyām | mádhubhyas |

| Ablative | śátros | śátrubhyām | śátrubhyas | mádhunas | mádhubhyām | mádhubhyas |

| Genitive | śátros | śátrvos | śátrūṇām | mádhunas | mádhunos | mádhūnām |

| Locative | śátrāu | śátrvos | śátruṣu | mádhuni | mádhunos | mádhuṣu |

| Vocative | śátro | śátrū | śátravas | mádhu | mádhunī | mádhūni |

Long Vowel-stems

| ā-stems (jā- 'progeny') | ī-stems (dhī- 'thought') | ū-stems (bhū- 'earth') | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Dual | Plural | |

| Nominative | jā́s | jāú | jā́s | dhī́s | dhíyāu | dhíyas | bhū́s | bhúvāu | bhúvas |

| Accusative | jā́m | jāú | jā́s, jás | dhíyam | dhíyāu | dhíyas | bhúvam | bhúvāu | bhúvas |

| Instrumental | jā́ | jā́bhyām | jā́bhis | dhiyā́ | dhībhyā́m | dhībhís | bhuvā́ | bhūbhyā́m | bhūbhís |

| Dative | jé | jā́bhyām | jā́bhyas | dhiyé, dhiyāí | dhībhyā́m | dhībhyás | bhuvé, bhuvāí | bhūbhyā́m | bhūbhyás |

| Ablative | jás | jā́bhyām | jā́bhyas | dhiyás, dhiyā́s | dhībhyā́m | dhībhyás | bhuvás, bhuvā́s | bhūbhyā́m | bhūbhyás |

| Genitive | jás | jós | jā́nām, jā́m | dhiyás, dhiyā́s | dhiyós | dhiyā́m, dhīnā́m | bhuvás, bhuvā́s | bhuvós | bhuvā́m, bhūnā́m |

| Locative | jí | jós | jā́su | dhiyí, dhiyā́m | dhiyós | dhīṣú | bhuví, bhuvā́m | bhuvós | bhūṣú |

| Vocative | jā́s | jāú | jā́s | dhī́s | dhiyāu | dhíyas | bhū́s | bhuvāu | bhúvas |

ṛ-stems

ṛ-stems are predominantly agental derivatives like dātṛ 'giver', though also include kinship terms like pitṛ́ 'father', mātṛ́ 'mother', and svásṛ 'sister'.

| Singular | Dual | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | pitā́ | pitárāu | pitáras |

| Accusative | pitáram | pitárāu | pitṝ́n |

| Instrumental | pitrā́ | pitṛ́bhyām | pitṛ́bhis |

| Dative | pitré | pitṛ́bhyām | pitṛ́bhyas |

| Ablative | pitúr | pitṛ́bhyām | pitṛ́bhyas |

| Genitive | pitúr | pitrós | pitṝṇā́m |

| Locative | pitári | pitrós | pitṛ́ṣu |

| Vocative | pítar | pitárāu | pitáras |

Personal pronouns and determiners

The first and second person pronouns are declined for the most part alike, having by analogy assimilated themselves with one another.

Note: Where two forms are given, the second is enclitic and an alternative form. Ablatives in singular and plural may be extended by the syllable -tas; thus mat or mattas, asmat or asmattas.

| First Person | Second Person | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Dual | Plural | |

| Nominative | aham | āvām | vayam | tvam | yuvām | yūyam |

| Accusative | mām, mā | āvām, nau | asmān, nas | tvām, tvā | yuvām, vām | yuṣmān, vas |

| Instrumental | mayā | āvābhyām | asmābhis | tvayā | yuvābhyām | yuṣmābhis |

| Dative | mahyam, me | āvābhyām, nau | asmabhyam, nas | tubhyam, te | yuvābhyām, vām | yuṣmabhyam, vas |

| Ablative | mat | āvābhyām | asmat | tvat | yuvābhyām | yuṣmat |

| Genitive | mama, me | āvayos, nau | asmākam, nas | tava, te | yuvayos, vām | yuṣmākam, vas |

| Locative | mayi | āvayos | asmāsu | tvayi | yuvayos | yuṣmāsu |

The demonstrative ta, declined below, also functions as the third person pronoun.

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Dual | Plural | Singular | Dual | Plural | |

| Nominative | sás | tāú | té | tát | té | tā́ni | sā́ | té | tā́s |

| Accusative | tám | tāú | tā́n | tát | té | tā́ni | tā́m | té | tā́s |

| Instrumental | téna | tā́bhyām | tāís | téna | tā́bhyām | tāís | táyā | tā́bhyām | tā́bhis |

| Dative | tásmāi | tā́bhyām | tébhyas | tásmāi | tā́bhyām | tébhyas | tásyāi | tā́bhyām | tā́bhyas |

| Ablative | tásmāt | tā́bhyām | tébhyam | tásmāt | tā́bhyām | tébhyam | tásyās | tā́bhyām | tā́bhyas |

| Genitive | tásya | táyos | téṣām | tásya | táyos | téṣām | tásyās | táyos | tā́sām |

| Locative | tásmin | táyos | téṣu | tásmin | táyos | téṣu | tásyām | táyos | tā́su |

Compounds

One other notable feature of the nominal system is the very common use of nominal compounds, which may be huge (10+ words) as in some modern languages such as German. Nominal compounds occur with various structures, however morphologically speaking they are essentially the same. Each noun (or adjective) is in its (weak) stem form, with only the final element receiving case inflection. Some examples of nominal compounds include:

- Dvandva (co-ordinative)

- These consist of two or more noun stems, connected in sense with 'and'. There are mainly two kinds of dvandva constructions in Sanskrit. The first is called itaretara dvandva, an enumerative compound word, the meaning of which refers to all its constituent members. The resultant compound word is in the dual or plural number and takes the gender of the final member in the compound construction. for example, rāma-lakşmaņau—Rama and Lakshmana, or rāma-lakşmaņa-bharata-śatrughnāh – Rama, Lakshmana, Bharata and Satrughna. The second kind is called samāhāra dvandva, a collective compound word, the meaning of which refers to the collection of its constituent members. The resultant compound word is in the singular number and is always neuter in gender. For example, pāņipādam—limbs, literally hands and feet, from pāņi = hand and pāda = foot. According to some grammarians, there is a third kind of dvandva, called ekaśeşa dvandva or residual compound, which takes the dual (or plural) form of only its final constituent member, for example, pitarau for mātā + pitā, mother + father, i.e. parents. According to other grammarians, however, the ekaśeşa is not properly a compound at all.

- Bahuvrīhi (possessive)

- Bahuvrīhi, or "much-rice," denotes a rich person—one who has much rice. Bahuvrīhi compounds refer (by example) to a compound noun with no head—a compound noun that refers to a thing which is itself not part of the compound. For example, "low-life" and "block-head" are bahuvrihi compounds, since a low-life is not a kind of life, and a block-head is not a kind of head. (And a much-rice is not a kind of rice.) Compare with more common, headed, compound nouns like "fly-ball" (a kind of ball) or "alley cat" (a kind of cat). Bahurvrīhis can often be translated by "possessing…" or "-ed;" for example, "possessing much rice," or "much riced."

- Tatpuruṣa (determinative)

- There are many tatpuruṣas (one for each of the nominal cases, and a few others besides); in a tatpuruṣa, the first component is in a case relationship with another. For example, a doghouse is a dative compound, a house for a dog. It would be called a "caturtitatpuruṣa" (caturti refers to the fourth case—that is, the dative). Incidentally, "tatpuruṣa" is a tatpuruṣa ("this man"—meaning someone's agent), while "caturtitatpuruṣa" is a karmadhārya, being both dative, and a tatpuruṣa. An easy way to understand it is to look at English examples of tatpuruṣas: "battlefield," where there is a genitive relationship between "field" and "battle," "a field of battle;" other examples include instrumental relationships ("thunderstruck") and locative relationships ("towndwelling").

- Karmadhāraya (descriptive)

- The relation of the first member to the last is appositional, attributive or adverbial, for example, uluka-yatu (owl+demon) is a demon in the shape of an owl.

- Amreḍita (iterative)

- Repetition of a word expresses repetitiveness, for example, dive-dive "day by day," "daily."

- Dvigu

Syntax

Because of Sanskrit's complex declension system the word order is free (with tendency toward SOV).

Numerals

The numbers from one to ten:

- éka-

- dva-

- tri-

- catúr-

- páñcan-

- ṣáṣ-

- saptán-

- aṣṭá-

- návan-

- dáśan-

The numbers one through four are declined. Éka is declined like a pronominal adjective, though the dual form does not occur. Dvá appears only in the dual. Trí and catúr are declined irregularly:

| Three | Four | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | Masculine | Neuter | Feminine | |

| Nominative | tráyas | trī́ṇi | tisrás | catvā́ras | catvā́ri | cátasras |

| Accusative | trīn | trī́ṇi | tisrás | catúras | catvā́ri | cátasras |

| Instrumental | tribhís | tisṛ́bhis | catúrbhis | catasṛ́bhis | ||

| Dative | tribhyás | tisṛ́bhyas | catúrbhyas | catasṛ́bhyas | ||

| Ablative | tribhyás | tisṛ́bhyas | catúrbhyas | catasṛ́bhyas | ||

| Genitive | triyāṇā́m | tisṛṇā́m | caturṇā́m | catasṛṇā́m | ||

| Locative | triṣú | tisṛ́ṣu | catúrṣu | catasṛ́ṣu | ||

Influence

Modern India

Influence on vernaculars

Sanskrit's greatest influence, presumably, is that which it exerted on languages that grew from its vocabulary and grammatical base. Especially among élite circles in India, Sanskrit is prized as a storehouse of scripture and the language of prayers in Hinduism. It is used as a liturgical language of Hinduism and Buddhism, and utilized occasionally in Jainism. Similar to the way in which Latin influenced European languages and Classical Chinese influenced East Asian languages, Sanskrit has influenced most Indian languages. While vernacular prayer is common, Sanskrit mantras are recited by millions of Hindus and most temple functions are conducted entirely in Sanskrit, often Vedic in form. Of modern day Indian languages, while Hindi and Urdu tend to be more heavily weighted with Arabic and Persian influence, Nepali, Bengali, Assamese, Konkani and Marathi still retain a largely Sanskrit vocabulary base. The national anthem, Jana Gana Mana, is written in a literary form of Bengali (known as shuddha bhasha), Sanskritized so as to be recognizable, but still archaic to the modern ear. The national song of India, Vande Mataram, originally a poem composed by Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay and taken from his book called 'Anandamath', is in a similarly highly Sanskritized Bengali. Malayalam, Telugu and Kannada also combine a great deal of Sanskrit vocabulary.

Sanskrit is one of the twenty-two official languages of India, and an ancestor of the modern Indo-Aryan languages. It has the same status in Nepal as well.

Revival efforts

The 1991 Indian census reported 49,736 fluent speakers of Sanskrit. Since the 1990s, efforts to revive spoken Sanskrit have been increasing. Many organizations like the Samskrta Bharati are conducting Speak Sanskrit workshops to popularize the language. The CBSE (Central Board of Secondary Education) in India has made Sanskrit a third language (though schools have the option to adopt it or not, the other choice being the state's own official language) in the schools it governs. In such schools, learning Sanskrit is an option for grades 5 to 8 (Classes V to VIII). This is true of most schools, including but not limited to Christian missionary schools, which are also affiliated to the ICSE board, especially in those states where the official language is Hindi. Sudharma, the only daily newspaper in Sanskrit, has been published out of Mysore in India since the year 1970.

Sanskrit is spoken natively by the population in Mattur village in central Karnataka. Inhabitants of all castes learn Sanskrit starting in childhood and converse in the language.[6]

Symbolic usage

In the Republic of India and Indonesia, Sanskrit phrases are widely used as mottoes for various educational and social organizations (much as Latin is used by some institutions in the West). The motto of the Republic is also in Sanskrit.

- Republic of India

- Satyameva Jayate

- Nepal

- Janani Janmabhūmis ca Svargād api garīyasi "Mother and motherland are greater than heaven"

- Goa

- Sarve Bhadrāni Paśyantu Mā Kaścid Duhkhabhāg bhavet

- Life Insurance Corporation of India

- Yogakshemam Vahāmyaham

- Indian Navy

- Shanno Varuna

- Indian Air Force

- Nābha Sparsham Dīptam

- Indian Police

- sadd rakshanay khalah nighranayah

- Indian Coast Guard

- Vayam Rakshāmaha

- All India Radio

- Bahujana-hitāya bahujana-sukhāya

- Indonesian Navy

- Jalesveva Jayamahe

- Aceh Province

- Pancacita

Many of the post–Independence educational institutions of national importance in India and Sri Lanka have Sanskrit mottoes.

Interactions with eastern and southeastern Asiatic languages

Sanskrit and related languages have also influenced their Sino-Tibetan-speaking neighbors to the north through the spread of Buddhist texts in translation.[7] Buddhism was spread to China by Mahayanist missionaries mostly through translations of Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit and Classical Sanskrit texts, and many terms were transliterated directly and added to the Chinese vocabulary. Although Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit is not Sanskrit, properly speaking, its vocabulary is substantially the same, both because of genetic relationship, and because of conscious imitation on the part of composers. Buddhist texts composed in Sanskrit proper were primarily found in philosophical schools like the Madhyamaka.

The Thai language contains many loan words from Sanskrit. For example, in Thai, the Rāvana, the legendary emperor of Lanka, is called 'Thoskanth' which is a derivation of his Sanskrit name "Dashakanth" ("of ten necks"). The influence extends as far as the Philippines, where the Tagalog for 'teacher' is 'gurò' from 'guru,' probably acquired from the Hindu seafarers who traded there. Many Sanskrit loanwords are also found in traditional Malay and Modern Indonesian, Old Javanese language (close to 50 percent) and Vietnamese.

Modern usage

Many of India's scientific discoveries and developments are named in Sanskrit, as a counterpart of the western practice of naming scientific developments in Latin or Greek. The Indian guided missile program that was commenced in 1983 by DRDO has named the five missiles (ballistic and others) that it has developed as Prithvi, Agni, Akash, Nag and Trishul. India's first modern fighter aircraft is named Tejas. This practice is usually followed in scientific institutions in India also.

Recital of Sanskrit shlokas as background chorus in films, television advertisements and as slogans for corporate organizations has become a trend.

Sanskrit has also made an appearance in Western pop music in recent years, in two recordings by Madonna. One, "Shanti/Ashtangi," from the 1998 album "Ray of Light," is the traditional Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga chant (referenced above) set to music. The second, "Cyber-raga," released in 2000, is a Sanskrit-language ode of devotion to a higher power and a wish for peace on earth. The climactic battle theme of The Matrix Revolutions features a choir singing Sanskrit prayer in the closing titles of the movie. Composer John Williams also featured a choir singing in Sanskrit for Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace.

The Sky One version of the title sequence in season one of Battlestar Galactica 2004 features the Gayatri Mantra, taken from the Rig Veda (3.62.10). The composition was written by miniseries composer Richard Gibbs.

Computational linguistics

There have been proposals to use Sanskrit as a metalanguage for knowledge representation in e.g. machine translation, and other areas of natural language processing, because of its highly regular structure. Classical Sanskrit is a regularized, prescriptivist form abstracted from the much more irregular and richer Vedic Sanskrit. This leveling of the grammar of Classical Sanskrit occurred during the Brahmana phase, after the language had fallen out of popular use.

See also

- Avestan

- Devanagari

- Sanskrit literature

- Sanskrit numerals

- Grantha Script

- Indo-European languages

- Languages of India

Notes

- ↑ Michael Witzel, Inside the Texts Beyond the Texts New Approaches to the Study of the Vedas (Harvard University Press, 1997, ISBN 978-1888789034)

- ↑ Thoams Oberlies, A Grammar of Epic Sanskrit (de Gruyter, 2003, ISBN 978-3110144482), XXIX.

- ↑ Bholanath Tiwari, Bhasha-vigyan (Illahabad: Kitab Mahal, 1978).

- ↑ William Dwight Whitney, Sanskrit Grammar (Dover Publications, 2003, ISBN 978-0486431369).

- ↑ Kashinath V. Abhyankar, A Dictionary of Sanskrit Grammar (Baroda: Oriental Institute, 1986).

- ↑ Times of India, This village speaks god's language. Retrieved November 18, 2007.

- ↑ Robert van Gulik, "Siddham; an essay on the history of Sanskrit studies in China and Japan," International Academy of Indian Culture, 1956.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Abhyankar, Kashinath V. A Dictionary of Sanskrit Grammar. Baroda: Oriental Institute, 1986.

- Burrow, T. The Sanskrit Language. London: Faber and Faber, 1955. ISBN 8120817672.

- Coulson, Michael, Richard Gombrich, and James D. Benson. Sanskrit: An Introduction to the Classical Language. Sevenoaks: Teach Yourself, 1992. ISBN 978-0340568675.

- Goldman, Robert P. Devavāṇīpraveśikā: An Introduction to the Sanskrit Language. Berkeley, CA: Center for South Asia Studies, University of California, 1999. ISBN 0944613403.

- Hall, Bruce Cameron. Sanskrit Pronunciation. Pasadena, CA: Theosophical University Press, 1992. ISBN 978-1557000217.

- Kale, Moreshwar Ramchandra. A Higher Sanskrit Grammar. Delhi: R.M. Lal, 1960. ISBN 8120801784.

- Macdonell, Arthur Anthony. A Sanskrit Grammar for Students. London: Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press, 1927. ISBN 8124600945.

- Maurer, Walter Harding. The Sanskrit Language: An Introductory Grammar and Reader. Surrey: Curzon Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0700703524.

- Oberlies, Thoams. A Grammar of Epic Sanskrit. de Gruyter, 2003. ISBN 978-3110144482.

- Shastri, Vagish. Vāgyoga Conversational Sanskrit. Varanasi: Vāgyoga Chetanāpitham, 2000. ISBN 8185570124.

- Tiwari, Bholanath. Bhasha-vigyan. Illahabad: Kitab Mahal, 1978.

- Whitney, William Dwight. Sanskrit Grammar. Dover Publications, 2003. ISBN 978-0486431369

- Williams, Monier. A Practical Grammar Of The Sanskrit Language Arranged With Reference To The Classical Languages Of Europe For The Use Of English Students. Oxford University Press, 1857.

- Witzel, Michael. Inside the Texts Beyond the Texts New Approaches to the Study of the Vedas. Harvard University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-1888789034.

External links

All links retrieved December 22, 2022.

- American Sanskrit Institute.

- Sanskrit at Ethnologue

- Sanskrit: The Language of Ancient India.

- GRETIL: Göttingen Register of Electronic Texts in Indian Languages, a cumulative register of the numerous download sites for electronic texts in Indian languages.

- Sanskrit texts at Sacred Text Archive.

- Clay Sanskrit Library publishes Sanskrit literature with facing-page text and translation. Also offers searchable corpus and numerous downloadable materials.

- Sanskrit and Tamil Dictionaries, searchable.

- The Sanskrit Heritage Dictionary.

- Sanskrit Dictionary.

- Glossary of Sanskrit Terms.

- Harivenu Dâsa: An Introductory Course based on S'rîla Jîva Gosvâmî's Grammar, a vaishnava version of Pânini's grammar (pdf-file).

- An Analytical Cross Referenced Sanskrit Grammar By Lennart Warnemyr. Phonology, morphology and syntax, written in a semiformal style with full paradigms.

|

||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 20:45:27 | 263 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Sanskrit | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed: KSF

KSF