Joseph Stilwell

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia Joseph Stilwell (1883 - 1946), was a senior American general in World War II as commander of American forces in the China-Burma-India (CBI) theater (1942–44) and commander of the main Chinese armies in Burma, with four-star rank, and, as commander in the late stages of the Battle of Okinawa in 1945. He was scheduled to lead the invasion of Japan when the war suddenly ended. "Vinegar Joe" was notoriously difficult to work with, especially in a role in China that was primarily diplomatic. Serving as chief of staff to Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek, the two battles endlessly about strategy and personalities. A fighting general who spoke Chinese and knew the villages well, he possessed a fierce integrity, and a hatred of incompetence and pretentiousness, but was sometimes devious and secretive. Postwar liberal historians have celebrated him as a hero for his opposition to Chiang.

Contents

Career[edit]

Stilwell was born in Palatka, Florida, where his wealthy parents were vacationing, and brought up in New York City. Both bookish and athletic, he was headed for Yale until his pranksterism caused his father to send him to West Point to be straightened out. Stilwell was graduated from West Point in 1904, and eagerly made a career in the Army. Stilwell spent years at West Point teaching French and Spanish, tactics, English, and history. He also coached basketball and football and was promoted to captain in 1916. In 1910 he married Winifred Alison Smith; they had five children. After service in the Philippines he was an intelligence officer (G-2) in the American Expeditionary Forces in France during World War I, playing a major role in organizing G-2 operations for the American offensive at Saint-Mihiel.

China[edit]

Stilwell, already noted for his language skills, became the army's first language officer in China, with service in Beijing (1920-1923), where he learned to speak Chinese. He helped the International Famine Relief Committee of the Red Cross as chief engineer on road-building projects in Shensi and Shansi provinces. There he lived and worked in the field with Chinese laborers and village officials, marched with the warlord armies, and came to know a China far beyond the foreigner's usual ken. His immense curiosity and powers of observation found expression, then and later, in his diary, where he recorded his impressions in vivid and voluminous detail.

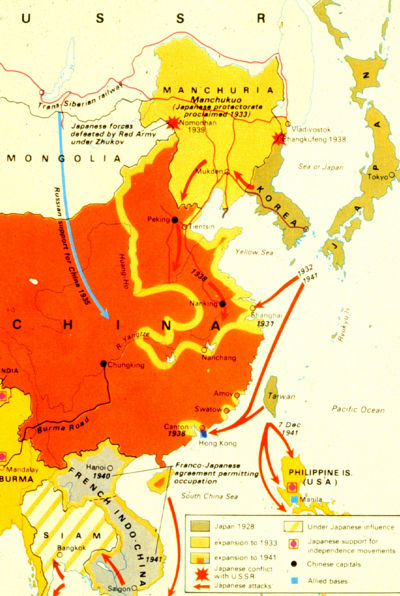

After attending the army's Infantry school at Ft. Benning and the Command and General Staff school at Fort Leavenworth, Stilwell returned to China (1926-1929) as battalion commander and later executive officer of the Fifteenth Infantry an American regiment stationed in Tientsin as a result of the Boxer Rebellion. He watched the Kuomintang under Chiang Kai-shek unify the nation, assessing Chinese affairs a series of weekly articles for the journal of the Fifteenth Infantry. His third China duty came in 1935–1939, when he returned as military attaché to observe, judge, and report the Japanese invasion, which began in 1937 and soon captured the major cities. Stilwell formed a negative opinion of KMT leadership and came to believe that Chinese soldiers, so hopelessly weak, ill-armed and poorly led in the war with Japan, could some day become the equal of any in the world, if they were properly led, trained, nourished, and equipped.

Army promotions[edit]

From 1929 to 1933, Stilwell served as chief of the tactical section at the Infantry School, under the direction of Col. George C. Marshall. Marshall had high praise for Stilwell as "a genius for instruction," who was "ahead of his time in tactics and technique," and, although personally unassuming, was one of the "exceptionally brilliant and cultured men of the army."[1] Stilwell was instantly repelled by incompetence or pretentiousness. A man of utter integrity, he was a fighter and a doer, whose too-quick disgust for anything less in others made him at times, as Marshall later said, "his own worst enemy."[2] His unsparing and acid critiques earned him the nickname "Vinegar Joe."

Marshall promoted his career and by late 1941, Stilwell had commanded the Third Infantry Brigade (1939), the Seventh Division (1940), and the III Corps (1940-1941) and had been promoted to major general (1940). By virtue of his training of troops and his mastery of tactics in troop maneuvers, he was rated the army's best corps commander. After Pearl Harbor Marshall brought him to Washington to command GYMNAST, a planned landing in North Africa, but that operation was postponed.

World War II[edit]

CBI[edit]

President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his top advisers, such as Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau and Lend-Lease administrator Harry Hopkins, were strongly committed to support China against Japan. Public opinion was strongly hostile to Japan; isolationism (opposition to war in Europe) played little role. Lend Lease aid began in 1940 with the goal of building a large powerful Chinese army that would hold down most of the Japanese army, and after the war play a role as a major world power in the United Nations. That goal was highly unrealistic, as Japan controlled the financial, economic and transportation centers in China, and most of the people, leaving the Nationalists in control in poor, remote mountainous regions, with their capital in Chungking. In addition, the Communists under Mao Zedong controlled their own remote sphere in the northwest. China was unable to feed or clothe its soldiers, who lacked equipment, discipline, and skilled sergeants, junior officers, and senior officers. Nevertheless, cost was no object and dollars poured in. After Pearl Harbor, the U.S. and Britain agreed to set up a China-Burma-India theater, with Chiang as supreme commander, and an American as chief of staff, and in command of American forces in China and Lend Lease supplies. The senior ranking American general Hugh A. Drum did not want the job, so Marshall called on Stilwell, and promoted him to Lieutenant General. Stilwell did not have a diplomatic bone in his body, and feuded incessantly with Chiang, with the British, and with his air commander Air Force Major General Claire L. Chennault, head of the Flying Tigers operation. Marshall supported Stilwell in these disputes, but Roosevelt and Chiang backed Chennault, who usually won.

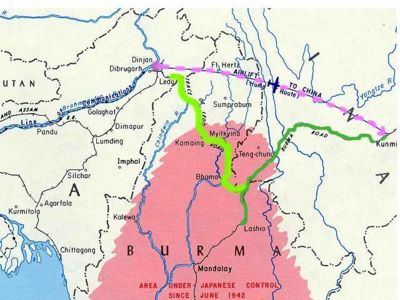

The American strategy was to build up air power in China, but not send significant numbers of American combat troops because they could not be easily supplied. Japan had long since cut off the coastline, and in March 1942 it cut the only overland road into China, the Burma Road. Supplies had to be flown in "over the Hump" (over the Himalayan mountains) from India at fantastic cost until the Ledo Road cutoff could be built and the Burma Road reopened. The British, meanwhile, had a low opinion of China's capabilities and gave minimal cooperation to Chiang and Stilwell. They considered Burma important not because it was a link to China, but because Japanese conquest threatened India. The British therefore conducted numerous large-scale campaigns in Burma, as did Stilwell. Coordination was weak. All were failures before the summer of 1944.

Command of Chinese forces[edit]

Arriving in Chungking in March 1942, Stilwell immediately began a counteroffensive to save Burma, but his command of the two Chinese divisions nominally under his direction was hamstrung by Chiang's remote control, and poor coordination with the British A worse problem was his own weak understanding of warfare. He had made his career in intelligence, not in command, and he had not attended the War College or command courses at Fort Leavenworth. He had no understanding of air power and remained wedded to World War One-style infantry offensives. He was easily outflanked by the Japanese, and Burma fell. Stilwell, rejecting an airlift, led a remnant of 114 men on a 140-mile march overland across the mountains to India. While the British were talking about strategic retreats he was frank: "I claim we got a hell of a beating."

The recovery of Burma became an obsession for him, and he began to think of himself as the one man who could save China. With few American ground troops available Stilwell decided to rebuild the Chinese army and use it to attack the Japanese in Burma. He demanded, with scant success, that airlifted supplies go to these operations, and not to Chennault's Air Force. The Chinese government desperately needed American aid just to survive, and realized that only the Americans could defeat Japan. Indeed, Chiang and his KMT saw that after the Japanese were defeated then the Communists would be their main foe, and they sought to hoard their military resources. Stilwell was given control of several Chinese divisions that had escaped to India, and which could be supplied with American equipment. He set out to systematically retrain them along American lines, with the long-term goal of eventually recruiting, training, and equipping sixty divisions in China. In mid-1943, besides his other titles, he became deputy supreme allied commander in Southeast Asia under Britain's Admiral Mountbatten.

Ledo Road[edit]

Stilwell made construction and defense of the Ledo Road a top priority. In the first seven months of 1944 Stilwell led Chinese troops in the successful battle to retake northern Burma. He used Merrill's Marauders an elite American Army unit of 3000 soldiers, and two small Chinese divisions, and had the cooperation of the Chindits, a British commando force. After terrible fighting to take the key junction city of Myitkyina, the American, Chinese and Japanese forces were all destroyed, but the Allies had captured Myitkyina and this allowed the Ledo-Burma road to be finished and open to road traffic in January, 1945.

Time and again Stilwell was frustrated and vehemently angry with the Chiang (whom he called "peanut") and the Chinese government. They refused to provide the soldiers and instead supported Chennault's plans. Chennault indeed obtained long-range B-29 bombers, and they started making raids on Japanese cities. The Japanese response, as Stilwell had long predicted, was an overland campaign (code-named "ICHI-GO") inside China to overrun Chennault's air bases in late summer 1944. Chiang finally forced the U.S. to recall Stilwell, who left in disgust in October, 1944, and was replaced by General Albert Wedemeyer (1897-1989), who got along much better with Chennault and Chiang.

Later career[edit]

Stilwell was given a training command stateside In June 1945, in the last stages of the Battle of Okinawa, the American commander was killed and Stilwell, now wearing four stars, took charge of the Tenth Army. His main mission was planning the invasion of the home islands of Japan, but that was unnecessary after Japan unexpectedly surrendered in August. His last command was of the Sixth Army in charge of the United States Western Defense Command. In October 1946, five months short of retirement, Stilwell died of stomach cancer.

Bibliography[edit]

see also China-Burma-India theater (CBI)/Bibliography

- Anders Leslie. The Ledo Road: General Joseph W. Stilwell's Highway to China. (1965).

- Bidwell, Shelford. The Chindit War: Stilwell, Wingate, and the Campaign in Burma, 1944. (1979)

- Byrd Martha. Chennault: Giving Wings to the Tiger. (1987). the standard biography

- Cornelius, Wanda, and Thayne Short. Ding Hao: America's Air War in China, 1937-1945. (1980)

- Dod, Karl C. The Corps of Engineers: The War against Japan. (1966),

- Liang, Chin-Tun. Gen. Stilwell in China, 1942-1944 (1972), a pro-Chiang view

- Newell, Clayton R. ‘’Burma, 1942'’ online edition, focus on Stilwell's operations

- Prefer, Nathan N. Vinegar Joe's War: Stilwell's Campaigns for Burma. (2000), 314pp; scholarly history online edition

- Romanus, Charles F. and Riley Sunderland. Stilwell's Mission to China (1953), official U.S. Army history online edition

- Romanus, Charles F. and Riley Sunderland. Stilwell's Command Problems (1956) online edition

- Schaller Michael. The U.S. Crusade in China, 1938-1945. (1979). online edition

- Tuchman, Barbara. Stilwell and the American Experience in China, 1911-45, (1972), 624pp; Pulitzer prize (The British edition is titled Against the Wind: Stilwell and the American Experience in China 1911-45,) excerpt and text search

- Ven, Hans Van De. "Stilwell in the Stocks: the Chinese Nationalists and the Allied Powers in the Second World War." Asian Affairs 2003 34(3): 243–259. Issn: 0306-8374 Fulltext: Ebsco, revisionist argument that Stilwell was incompetent, had no command training or experience, and did not appreciate air power. Ven suggests that Roosevelt's needs in the presidential election of 1944, the strategic decision to defeat the Nazi menace in Europe before giving full attention to Japan, and the unwise yielding to the needs of the Soviet Union during World War II all led to the defeat of the Chinese Nationalists.

- Ven, Hans van de. War and Nationalism in China: 1925-1945 (2003), negative on Stilwell

- Young, Kenneth Ray. "The Stilwell Controversy: A Bibliographical Review," Military Affairs, Vol. 39, No. 2 (Apr., 1975), pp. 66–68 in JSTOR

Primary Sources[edit]

- Stilwell, Joseph Warren. The Stilwell papers edited by Theodore H. White, (1958).

See also[edit]

- Burma Road and Ledo Road

- CBI China-Burma-India theater

- Chiang Kai-shek

- Claire Chennault

- Okinawa, battle of

Online resources[edit]

notes[edit]

- ↑ Barbara Wertheim Tuchman, Stilwell and the American Experience in China, 1911-45 (1970) online p.125

- ↑ Tuchman, Stilwell, p. 425 online

Categories: [Chinese History] [World War II Commanders]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/26/2023 09:08:09 | 3 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Joseph_Stilwell | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF