Mexican-American War

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia Contents

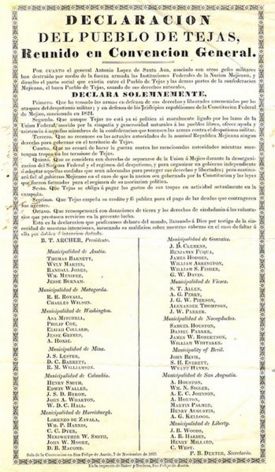

Buildup to War[edit]

Causes[edit]

The basic cause of this war from the Mexican side was the refusal to recognize the independence of Texas, which successfully revolted in 1836. In ten years as an independent republic Texas was recognized by the major nations of the world, most notably Britain and France, but not by Mexico. Mexican politicians promised that if the U.S. ever annexed Texas it would mean war. Annexation took place in 1845 and war promptly followed. From the American side, one of the causes was the goal of "Manifest Destiny" especially appealed to Democrats; Whigs strenuously opposed the idea. The war them was driven by the idea of a "Manifest Destiny" that some Americans believed was a God-given right to control the North American continent.[1] The election of 1844 of President James K. Polk, a Democrat who believed in expansion, set in train the annexation and an offer to purchase California, which Mexico rejected.

From the borderland perspective, Mexico had forfeited its control. It withdrew most army units to engage in civil wars for political power, leaving the border region defenseless against repeated large-scale Indian raids. The Hispanics in Texas ("tejanos") and New Mexico ("nuevo-mexicanos") were affiliating more with the U.S. in terms of economy and security, and useless welcomed the American takeover.

Along the border[edit]

Delay (2007) and Reséndez (2004) explain the American need to suppress Indian raids originating from Mexican territory. During the 1830s and 1840s, northern Mexico experienced a terrifying increase in inter ethnic violence as Comanches, Kiowas, Apaches, and other Indians attacked Mexican settlements across nine states in northern Mexico. Raids claimed thousands of lives, ruined the ranching and mining industries, and forced most Hispanics to flee the border region. Just as importantly, the violence shaped how Americans and Mexicans came to view each other in advance of the war. US observers saw Indians driving Mexicans backward, with the government there uninterested and incapable of defending the territory it had seized from Spain. With the Mexican army being used primarily to wage political battles for control of the government, Hispanic residents of the affected areas despaired that their government would help them; they increasingly welcomed American intervention, which they correctly expected would end the Indian raids. Mexican politicians complained Washington was fomenting Indian raids in order to acquire territory.

Meanwhile, in New Mexico, the economy and society were becoming integrated with the U.S. and nuevo-mexicanos were increasingly estranged from Mexico. Some Catholic priests tried to prevent full integration by restricting marriages between Protestant American men and Mexican Catholic women. By 1846 little fervor existed in New Mexico for resisting the American army. Consequently, the Mexican army did not attempt to defend New Mexico or California. Some Hispanics after the war went to Mexico; (in Laredo the whole town); most of the tejanos, californios and nuevo-mexicanos preferred American rule; unfortunately some of them were murdered or, in many cases, dispossessed of their private properties. Disputes over land titles became endemic.[2] [3][4]

In Mexico[edit]

In Mexico itself, Henderson (2007) emphasizes that Mexican agency in going to war reflected a profound sense of weakness. Mexico's revolutionary experience had produced a virulent factionalism based on divisions of race, class, region and ideology. The success by Tejas in 1836 only made it more clear that Mexico was too weak to populate, control and defend its northern territories, but that opinion was derided by Mexican politicians. Instead, they all denounced the policies of their rivals. The only common denominator was that Tejas must be reconquered, even if that meant war with overwhelmingly superior U.S. military and economic power.

In any case Mexico was in not a good position to negotiate with the U.S. because of its instability. In 1846 alone the presidency changed hands 4 times, the war minister changed 6 times, the finance minister changed 16 times.[5] As one Mexican historian explains:[6]

- "Mexican public opinion and all the various political factions that aspired to or that actually shared in power at that time, had to—willingly or unwillingly—participate in a very hawkish attitude toward the war. Anyone who tried to avoid open conflict with the United States was treated as a traitor. That was precisely the case of President José Joaquin de Herrera. At one time he, at least, seriously considered receiving the American special envoy, John Slidell, in order to negotiate the problem of Tejas annexation peacefully. But as soon as he assumed that position, the president was accused of favoring the handing over of a part of national territory; he was accused of treason and was overthrown."

Mexico was not a democratic country. The Mexican people as a whole remained largely indifferent—otherwise Winfield Scott's landing at Vera Cruz and his decisive march on Mexico City would have been impossible. Mexico, unable to pursue a pragmatic strategy of negotiation and compromise, suffered—and celebrated—a "glorious defeat" that further unraveled a disunited nation.

Manifest Destiny[edit]

Support for the war among Democrats stemmed in part from the popular notion of Manifest Destiny. This belief held that it was the American peoples' birthright to control the whole of the American continent. The Whig Party rejected Manifest Destiny, opposed annexation of Tejas, and opposed the war from beginning to end. Antislavery forces feared it would be used to spread slavery. Expansionist James K. Polk was sworn into office in March 1845 after winning election on the promise of annexing Tejas.

Disputed border region[edit]

Start of war[edit]

Shortly after the U.S. Congress, by joint resolution, annexed Texas in 1845, the Mexican government recalled its minister from Washington and broke off diplomatic relations. Government newspapers in Mexico City acted as if war already existed. On June 15, 1845, Brevet Brigadier General Zachary Taylor, commanding American troops in the southwest, received orders to move forward into some disputed territory (not in Tejas but in Nuevo Santander) "on or near the Rio Grande." In August he encamped on the west bank of the Nueces River, Tejas. President Polk then sent John Slidell of New Orleans to Mexico City with a proposal to adjust the boundary dispute, and to purchase Upper California and New Mexico. Mexico rejected Slidell's mission, and rejected efforts by Britain to broker a compromise. It was time for war.

A no-man's land between the Rio Grande and Nueces River was disputed between the United States and Mexico. The borders of the region were fortified with troops from both nations. When the Mexican government refused to negotiate with Slidell, Polk on Jan. 3, 1846, instructed Taylor to advance. Within a month Taylor's forces were at the Rio Grande. On April 12 General Pedro Ampudia demanded that Taylor retreat beyond the Nueces. Taylor held his position, and on April 24 a Mexican force ambushed a party of American dragoons on the north side of the Rio Grande.[7] On May 11 Polk's war message went to Congress, declaring that "American blood has been shed on American soil," affirming the American position that the Rio Grande was the southern border of the United States. A war appropriation bill providing for enlistments passed both houses by overwhelming margins. Its preamble declared that the war existed by the act of Mexico. War was officially declared by the United States on May 13, and Mexico followed suit on July 7, 1846.

Overview of War[edit]

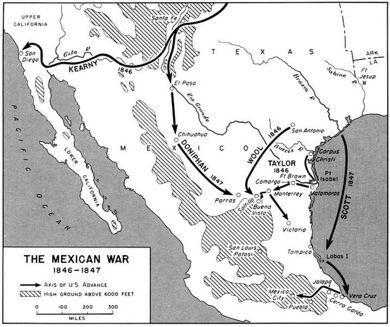

The war was popular throughout the South and West, as volunteers rushed to enlist in new regiments, which fought alongside the regular U.S. Army units. The U.S. invaded northern Mexico from two directions, in an attempt to quickly seize lands and force an early surrender. Colonel Stephen Kearny commanded the forces that headed west from Kansas to Santa Fe (and later to California) to reinforce Captain John C. Frémont, who arrived from the north. The second front was opened by General Zachary Taylor, who moved southward after repetitive victories against the defending Ejército del Norte (Army of the North).

New Mexico[edit]

The American strategy called for the occupation of New Mexico and California, a blockade of the Mexican coasts, and a principal thrust toward Mexico City. On Aug. 18, 1846, General Stephen W. Kearny, after an 850-mile (1,370-km) overland advance, occupied Santa Fe, New Mexico, with a force of 1,700 men.California[edit]

Kearny continued on to California at the head of his cavalry, and fought a small engagement at San Pascual on December 6, 1846, before reaching San Diego. The U.S. Navy commanded first by Commodore John D. Sloat then by Commodore R. F. Stockton, played the major role in the conquest of California, aided by colonel John C. Frémont and his 60-man army detachment which entered from the north and took control of Sonoma and Monterrey, where a "Bear Flag" movement had overthrown the local Mexican officials. The U.S. Navy, under command of Commodore Stockton, soon arrived and put Frémont's forces under its command. The combined forces occupied San Francisco, Monterey, Sonoma, Sacramento, and Los Angeles by August. The American troops in Los Angeles held out against "Californios" (ethnic Mexicans living in California) until January 1847, when the local Treaty of Cahuenga was signed (it was not an official treaty between nations).

Northern Mexico[edit]

During the early phases of the war, the most important fighting was in northeastern Mexico. After the battles of Palo Alto on May 8, 1846, and Resaca de la Palma on May 9, Taylor's army followed the retreating Mexicans across the Rio Grande, occupied Matamoros, and advanced to Monterrey, capital of Nuevo León province. In September, he captured the large city of Monterey after a three-day battle. After the battle, a temporary truce was enacted, during which the Mexican government refused to make peace. The turmoil in Mexico allowed former President Antonio López de Santa Anna to gain re-election. A fresh army of 20,000 men was trained by the new president.

Battle of Buena Vista[edit]

In February 1847, near the small outpost of Buena Vista, Taylor and his 4,800 regulars faced an army of about 15,000 Mexican soldiers led by General Santa Anna. What might have been a rout ended up in an American victory, with the American troops maneuvering quickly and regrouping in order to keep the surrounding Mexican troops from completely overrunning their position. On February 20, Taylor occupied an exposed position at Agua Nueva. When he learned that Santa Anna was approaching, Taylor retreated along a road 12 miles (19 km) toward Saltillo. Halting near the northern end of a mountain pass at the hacienda of Buena Vista, Taylor enfiladed with artillery the deep gullies that creased most of the pass. When skirmishing began on February 22, it became apparent that Taylor lacked sufficient strength on the American left, where the Mexicans were able to approach along the shallow end of lateral ravines and on the slopes of the adjoining mountains. The next morning the Mexican thrust pushed back the American left flank. As Santa Anna's troops poured through to the hacienda, Taylor threw in his reserves and with the invaluable aid of Jefferson Davis's Mississippi Rifles regiment, checked the retreat. Artillery batteries of Braxton Bragg, J. M. Washington, and Thomas W. Sherman cut down further Mexican attacks (?). Taylor then reorganized his line toward the east, and by nightfall had recovered the lost ground (?). During the night the Mexican army began its retreat. The American losses were 746; reported Mexican losses (including prisoners and deserters) were 3,494. Buena Vista was an important battle of the war; Santa Anna inexplicably withdraw, as apparently it was a Mexican victory, leaving the battle camp.[8] Taylor advance was stopped.

Military operations in 1847[edit]

See also: U.S. Marines fight in the Battle of Chapultepec

After General John E. Wool failed to take Chihuahua, Colonel A. W. Doniphan with 850 men entered the city on March 1, 1847. which fell after siege and assault, September 21–23, 1846. Large elements of Taylor's army were shifted to Scott's command to form an invasion force coming from another direction—from the sea.

On March 9, 1847, in the largest amphibious landing in history up to that time, General Winfield Scott brought 12,000 men ashore at Veracruz, Mexico; the city suffered a siege and a three days and nights bombardment with an important number of civilians casualties. The surrender and occupation of the city took place on March 29.

Polk gave Scott command of this force, largely in an attempt to quiet the public's love of Taylor. Polk, a Democrat, feared that Taylor, a Whig, would use his popularity as a war hero to unseat him in the next election.

Cerro Gordo[edit]

The Americans then turned toward Mexico City, and at Cerro Gordo, April 17–18, 1847, faced another army under Santa Anna. The battle was fought along the route of the Mexican national highway, at a narrow defile in rugged foothills 50 miles (80 km) northwest of Veracruz. Scott invading army numbered 8,500 and Santa Anna's Mexican defenders numbered 12,000. Fearful of the yellow fever season after the capture of Veracruz, Scott hurried his men toward the highlands and Mexico City. Santa Anna prepared defenses at a pass just below Cerro Gordo. At the suggestion of Captain Robert E. Lee, Brigadier General David E. Twiggs's division left the highway some distance from the Mexican position and struck out in a flanking movement over rough terrain. On April 17, Twiggs's men occupied one defended height, and the next day Colonel W. S. Harney's command stormed the main defensive bastion. Simultaneously, Brigadier General James Shield's brigade struck hard against the extreme left flank of the Mexican army as it fled down narrow paths into the canyon of Río del Plan. The Mexicans lost 1,200 men and the Americans 431. This was Scott's last major battle before he reached the Valley of Mexico.

Chapultepec[edit]

Santa Anna refused to negotiate so Scott invaded the Valley of Mexico. There he won the important battles of Contreras and Churubusco, August 19–20, 1847. When another armistice failed to bring peace, Scott's men won the bloody battle of Molino del Rey on September 8, and reached Mexican positions on Chapultepec Hill, September 12, which were the key to the inner defenses of Mexico City. Contrary to the advice of his best engineers, Scott decided to enter Mexico City by causeways leading to its western gates. This course required taking Chapultepec Hill, 200 feet (60 meters) high. In addition to natural defenses it had for protection an array of high walls, ditches, and parapets. On its crest a garrison held a group of military college buildings, and at the approaches Santa Ana placed troops which were about equal in number to the 7,180 Scott employed in the operations. On September 12, American artillery opened fire on the fort. The next morning, Scott sent Brigadier General John A. Quitman's division, with a select storming party from Twiggs's division, against the south and east walls of the Chapultepec enclosure. Simultaneously, Brigadier General Gideon J. Pillow's division fought its way forward from the west. Finally the attackers reached the western walls, hoisted scaling ladders, and in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter fought their way to the upper ramparts on the top of the hill. Thereupon the garrison's commander surrendered the site that had once been the residence of the Spanish viceroys, and Mexico City lay open. In the fighting Santa Ana lost about 1,800 men, including those missing; estimated American losses were 450. The city surrendered on September 14. Santa Anna escaped, and soon resigned.[9]The last building to hold out against Scott was a military academy at Chapultepec Castle.

U.S. Politics[edit]

Volunteer army[edit]

As regimental commanders, volunteer colonels were vital to American military efforts, raising units of volunteer soldiers who agreed to serve outside US boundaries. The came from western states, especially Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Arkansas, and Mississippi. Of the 63 volunteer colonels on active duty in 1846, 14 belonged to the Whig Party, indicating that Whigs were not monolithic in their opposition to the war. The colonels accumulated a mixed wartime record of leadership, and their backgrounds varied greatly. Some had no military experience prior to 1846, but others had graduated from West Point, served in the regular army, seen combat in war or on the frontier, or held rank in a state militia. The colonels also varied widely in holding political office before and after the war. Several of them were experienced politicians before 1846 who also held important offices after the war, showing that most colonels were recognized figures in their home states.[10]

Combat lessons[edit]

Many of the senior commanders on both sides of the U.S. Civil War, including Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant, gained military experience fighting Mexico. Most useful to Grant was the insight he gained about the Confederate generals, explaining "The Mexican War made the officers of the old regular armies more or less acquainted, and when we knew the name of the general opposing we knew enough about him to make our plans accordingly. What determined my attack on Fort Donelson was as much the knowledge I had gained of its commanders in Mexico as anything else." Lee discovered the enormous value of intelligent reconnaissance and the dramatic effect of a well-executed swift-striking flanking movement. During the Civil War, Lee relied heavily on thorough reconnaissance. Lee's flanking movement at Chancellorsville echoed Scott's at Cerro Gordo. George B. McClellan learned the value of for sieges, rooted in an admiration of the one Scott clamped on Vera Cruz. In his Peninsula Campaign in the Civil War in 1862 he McClellen a month-long siege of Yorktown against inferior Confederate numbers; most historians agree he should instead have boldly attacked. Like Lee, Stonewall Jackson learned the value of a swift-striking flanking movement and applied that lesson brilliantly in his Shenandoah Valley campaign, and in commanding the great flanking movement under Lee at Chancellorsville. Samuel Dupont was among the Navy captains who conducted a limited naval blockade of Mexican ports, which he carried over, expanded, and used to effect in the Union blockade of Confederate ports. Joseph Hooker learned military management in Mexico and used it to great effect to reorganize the Union armies before Chancellorsville in 1863. But at Chancellorsville his army fell victim to what Lee and Jackson remembered and Hooker forgot about swift flanking movements. James Longstreet experienced costly offensive warfare in Mexico, and was seriously wounded in the charge at Chapultepec. He became a strong advocate of defensive warfare in the Civil War, famously employing it at Fredericksburg and unsuccessfully urging it on Lee at Gettysburg.[11]

Antiwar sentiments[edit]

Politically, the Democratic party rallied behind Polk and strongly supported the war. The Whig Party has opposed the annexation of Texas and generally opposed the war. Some opponents (like Army lieutenant Ulysses S. Grant) believed the war constituted an unjust aggression against helpless Mexico. Henry Clay and many Whigs opposed geographical expansion because they wanted vertical modernization (based on industry and banking), rather than more-of-the-same farmland. Antislavery elements in New England saw the war as a conspiracy by southern slave owners—called the Slave Power—to expand their holdings. (Historians after 1900 agreed that allegation was untrue.) The author and future diplomat James Russell Lowell wrote the poem "Once to Every Man and Nation" as a protest against pro-war agitation in 1845; it is still sung today as a hymn in many churches. Henry David Thoreau refused to pay his state poll tax in 1846 as a symbolic protest against the war and slavery. Thoreau spent one night in jail as a result. The incident eventually led to his writing Civil Disobedience (1849). Still other dissenters feared the war might undercut republican values by transforming the United States from a republic to a grasping militaristic empire. Typical opponents used several different arguments, to no avail.

Generally, the officers of the army were indifferent whether the annexation was consummated or not; but not so all of them. For myself, I was bitterly opposed to the measure, and to this day regard the war, which resulted, as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic following the bad example of European monarchies, in not considering justice in their desire to acquire additional territory." General Ulysses S. Grant.

Abraham Lincoln a new member of Congress from Illinois, was not a particularly powerful or influential figure, but he was articulate in denouncing the war, which he attributed to Polk's desire for "military glory — that attractive rainbow, that rises in showers of blood." He also challenged the President's claims regarding the Texas boundary and offered a resolution (which did not pass) demanding to know on what "spot" on US soil that blood was first spilt.[12] In January 1848, he was among the 82 Whigs who defeated 81 Democrats in a procedural vote to add to a routine bill the words "a war unnecessarily and unconstitutionally begun by the President of the United States." The amendment passed, but the bill never reemerged from committee and was never finally voted upon.

Lincoln damaged his political reputation in Illinois with a speech in which he declared, "God of Heaven has forgotten to defend the weak and innocent, and permitted the strong band of murderers and demons from hell to kill men, women, and children, and lay waste and pillage the land of the just." Two weeks later, President Polk sent a peace treaty to Congress. While no one in Washington paid any attention to Lincoln, the Democrats orchestrated angry outbursts from across his district, where the war was popular and many men had volunteered. In one county, Democrats set up mass meetings that adopted resolutions denouncing the "treasonable assaults of guerrillas at home; party demagogues; slanderers of the President; defenders of the butchery at the Alamo; traducers of the heroism at San Jacinto." Warned by his law partner that the political damage was mounting and irreparable, Lincoln decided not to run for reelection. Instead in fall 1848 he campaigned vigorously for Taylor, the successful general whose atrocities he had denounced in January. Regardless, Lincoln's harsh words were not soon forgotten, and haunted him during the Civil War.[13]

- We certainly assumed a great moral responsibility when we annexed Texas. However, it was not to Mexico that we were answerable, but to the enlightened conscience of the nation. The Moral Aspect of the Annexation of Texas.[14]

Peace[edit]

On November 22, 1847, a new Mexican government announced the appointment of peace commissioners, who negotiated with Nicholas P. Trist, the American peace commissioner, to draw up the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which was signed Feb. 2, 1848.

Military Operations in 1848[edit]

Santa Cruz de Rosales[edit]

Brigadier General Sterling Price, commander of U.S forces in New Mexico, got information indicating that Mexican general Jose de Urrea was advancing. Therefore, price left El Paso with 200 men and headed to Santa Cruz de Rosales in Chihuahua, Mexico.

On March 16, 1848, Price assaulted and captured the town of Santa Cruz de Rosales within 2 hours. [15]

Todos Santos[edit]

On March 26, 1848, Colonel Burton, Captain Naglee and Lt. Halleck along with 217 men, set out for San Antonio located in Baja California, Mexico. The day after, a detachment of 15 American troops surprised the Mexican forces at San Antonio and captured a Mexican commander by the name of Manuel Pineda. Burton found out that Mexican troops under the command of Mauricio Castro, were concentrating at Todos Santos before they planned to retreat to Magdelena Bay. Burton wanted to quickly attack them before they could do this.

On March 30, Burton sent Captain Naglee and 45 men to attack the Mexican forces from the rear. Due to a warning about a planned ambush by the Mexican forces, Burton directed his detachment along a ridge of high tableland, from which he was able to view the enemy forces, which consisted of about 200-300 Mexican and Yaqui indigenous peoples. The Mexican force then fell back to a hill overlooking Burton's force.

Eventually, the Mexican forces fired on Burton's men and after being engaged for some time, Naglee's company charged from behind, routing the Mexican force by 5:30 P.M. The skirmish cost the Mexicans 10 men and the Americans none. [16]

Consequences of the War[edit]

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed in February 1848, after Mexico's final surrender following the fall of Mexico City.

Mexican Cession[edit]

Mexico ceded vast amounts of land to the north (what would become Texas, California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, Arizona and parts of Wyoming, and Colorado), for $15 million that was not completely paid.

War Heroes[edit]

General Taylor, nicknamed "Old Rough and Ready" used his popularity to win the Presidency in 1848, despite Polk's efforts to prevent such an election. Other generals would also run for president, including the Republican Party's first candidate, John C. Frémont. The war also provided experience for the men who would be leaders during the soon-to-come American Civil War, including Ambrose Burnside, Robert E. Lee, Winfield Scott, James Longstreet, Ulysses S. Grant, "Stonewall" Jackson, George McClellan, Jefferson Davis, and George Meade

Four teenage Mexican cadets (the youngest of whom was thirteen years old) and their 20-year-old lieutenant squadron leader fought to the death to defend their city. El Día de Los Niños Héroes de Chapultepec (Day of the Boy Heroes of Chapultepec) is celebrated every September 13 in Mexico, the anniversary of the battle, and honors the bravery of the boys.

New Mexican nationalism[edit]

Basically, I feel tremendously sad that we lost our original territory, and that the experience of having an invader in our country was so brutal. But, on the other hand, I do believe — and I agree with the writers of "Apuntes" — that, as Mexicans, this painful experience forced us to reevaluate our country. I think that in history nothing ever happens that is totally bad or totally good. [17] A Conversation with Jesús Velasco-Márquez, Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México.

War Cost[edit]

Financially, the war in the long run cost the US$147 million, including $73 for direct costs, $64 million for veterans benefits, and $10 million in interest charges on war loans. A total of 101,000 American soldiers were mobilized, including 27,000 regulars and 74,000 volunteers; the typical volunteer served for 10 months. Deaths in battle totaled 1,549; another 11,000 died from disease and accident.[18] Mexican losses were much higher—perhaps 25,000 dead—but accurate data is lacking.

Further reading[edit]

for a more detailed guide the Bibliography below.

- Bauer K. Jack. The Mexican War, 1846-1848. (1974), good on military action.

- Brack, Gene M. "Mexican Opinion, American Racism, and the War of 1846," Western Historical Quarterly Vol. 1, No. 2 (Apr., 1970), pp. 161–174 in JSTOR

- Crawford, Mark; Heidler, Jeanne T.; Heidler, David Stephen, eds. Encyclopedia of the Mexican War (1999), thorough overview by scholars (ISBN 157607059X)

- De Voto, Bernard, Year of Decision 1846 (1942), very well written popular history

- Fowler, Will. Santa Anna of Mexico (2007) 527pp; the major scholarly study excerpt and text search

- Frazier, Donald S. ed. The U.S. and Mexico at War, (1998), 584; a good encyclopedia with 600 articles by 200 scholars

- Hamilton, Holman, Zachary Taylor: Soldier of the Republic (1941)

- Heidler, David S. and Heidler, Jeanne T. The Mexican War. (2005). 225 pp. basic survey, with some key primary sources

- Henderson, Timothy J. A Glorious Defeat: Mexico and Its War with the United States (2007), survey excerpt and text searchexcerpt and text search

- Johnson, Timothy D. Winfield Scott: The Quest for Military Glory (1998)

- Meed, Douglas. The Mexican War, 1846-1848 (2003). 96pp by British scholar excerpt and text search

- Sellers Charles G. James K. Polk: Continentalist, 1843-1846 (1966), the standard biography vol 1 and 2 are online at ACLS e-books

- Smith, Justin H. The War with Mexico 2 vol (1919); Pulitzer Prize; very thorough coverage; online vol 1; online vol 2 Pulitzer Prize winner.

- Smith, Justin H. "American Rule in Mexico," The American Historical Review Vol. 23, No. 2 (Jan., 1918), pp. 287–302 in JSTOR

Advanced Bibliography[edit]

Surveys[edit]

- Bancroft, H.H. History of California (1888) online edition

- Bauer K. Jack. The Mexican War, 1846-1848. Macmillan, 1974.

- Crawford, Mark; Heidler, Jeanne T.; Heidler, David Stephen, eds. Encyclopedia of the Mexican War (1999) (ISBN 157607059X)

- De Voto, Bernard, Year of Decision 1846 (1942), very well written popular history

- Frazier, Donald S. ed. The U.S. and Mexico at War, (1998), 584; an encyclopedia with 600 articles by 200 scholars

- Heidler, David S. and Heidler, Jeanne T. The Mexican War.Greenwood, 2005. 225 pp. basic survey, with some key primary sources

- Meed, Douglas. The Mexican War, 1846-1848 (2003). 96pp by British scholar excerpt and text search

- Smith, Justin H. The War with Mexico 2 vol (1919); Pulitzer Prize; 2:233-52; online vol 1; online vol 2 Pulitzer Prize winner.

Military[edit]

- Bauer, K. Jack. Zachary Taylor: Soldier, Planter, Statesman of the Old Southwest. (1985).

- Bauer K. Jack. The Mexican War, 1846-1848. (1974) very good military history.

- Bauer, K. Jack. "The Veracruz Expedition of 1847," Military Affairs Vol. 20, No. 3 (Autumn, 1956), pp. 162–169 in JSTOR

- Kevin Dougherty. Civil War Leadership and Mexican War Experience (2007)

- Eisenhower, John. So Far From God: The U.S. War with Mexico, (1989) excerpt and text search

- Foos, Paul. A Short, Offhand, Killing Affair: Soldiers and Social Conflict during the Mexican War (2002) excerpt and text search

- Hamilton, Holman, Zachary Taylor: Soldier of the Republic , (1941)

- Johnson, Timothy D. Winfield Scott: The Quest for Military Glory (1998)

- Lavender, David. Climax at Buena Vista: The Decisive Battle of the Mexican-American War (2003) excerpt and text search

- Lewis, Lloyd. Captain Sam Grant (1950)

- McCaffrey, James M. Army of Manifest Destiny: The American Soldier in the Mexican War, 1846-1848 (1994)excerpt and text search

- Winders, Richard Price. Mr. Polk's Army (1997) excerpt and text search

Political and Diplomatic[edit]

- Gleijeses, Piero. "A Brush with Mexico" Diplomatic History 2005 29(2): 223–254. Issn: 0145–2096; debates in Washington before war. fulltext in EBSCO

- Graebner, Norman A. Empire on the Pacific: A Study in American Continental Expansion. (1955).

- Graebner, Norman A. "Lessons of the Mexican War." Pacific Historical Review 47 (1978): 325–42. in JSTOR

- Graebner, Norman A. "The Mexican War: A Study in Causation." Pacific Historical Review 49 (1980): 405–26. in JSTOR

- McCormac, Eugene Irving. James K. Polk: A Political Biography (1922) online edition

- Pletcher David M. The Diplomacy of Annexation: Texas, Oregon, and the Mexican War (1973).

- Rives, George L. "Mexican Diplomacy on the Eve of War with the United States," The American Historical Review Vol. 18, No. 2 (Jan., 1913), pp. 275–294 in JSTOR

- Rives, George Lockhart. The United States and Mexico, 1821-1848 (2 vol 1913) vol 1 to end of 1845

- Schroeder John H. Mr. Polk's War: American Opposition and Dissent, 1846-1848. 1973.

- Sellers Charles G. James K. Polk: Continentalist, 1843-1846 (1966), the standard biography vol 1 and 2 are online at ACLS e-books

- Smith, Justin H. The War with Mexico 2 vol (1919); Pulitzer Prize; 2:233-52; online vol 1; online vol 2 Pulitzer Prize winner.

- Streeby, Shelley. "American Sensations: Empire, Amnesia, and the US-Mexican War," American Literary History Vol. 13, No. 1 (Spring, 2001), pp. 1–40 in JSTOR

- Weinberg Albert K. Manifest Destiny: A Study of Nationalist Expansionism in American History (1935). ACLS e-book

Hispanic perspectives[edit]

- Bancroft, H. H. History of Mexico: 1824-1861 (1885) online edition

- Brack, Gene M. Mexico Views Manifest Destiny, 1821-1846: An Essay on the Origins of the Mexican War (1975).

- Brack, Gene M. "Mexican Opinion, American Racism, and the War of 1846," The Western Historical Quarterly Vol. 1, No. 2 (Apr., 1970), pp. 161–174 in JSTOR

- Castañeda, Carlos E. "Relations of General Scott with Santa Anna," The Hispanic American Historical Review Vol. 29, No. 4 (Nov., 1949), pp. 455–473 in JSTOR

- Delay, Brian. "Independent Indians and the U.S.-Mexican War." American Historical Review 2007 112(1): 35–68. Issn: 0002-8762 Fulltext: History Cooperative

- Fowler, Will. Santa Anna of Mexico (2007) 527pp; the major scholarly study excerpt and text searchonline edition

- Fowler, Will. Tornel and Santa Anna: The Writer and the Caudillo, Mexico, 1795-1853 (2000)

- Henderson, Timothy J. A Glorious Defeat: Mexico and Its War with the United States (2007), survey excerpt and text searchexcerpt and text search

- Krauze, Enrique. Mexico: Biography of Power, (1997)

- Levinson, Irving W. Wars Within War: Mexican Guerrillas, Domestic Elites, And The United States Of America, 1846-1848 (2005) except and text search

- McCornack, Richard Blaine. "The San Patricio Deserters in the Mexican War," The Americas Vol. 8, No. 2 (Oct., 1951), pp. 131–142 in JSTOR

- Mayers, David; Fernández Bravo, Sergio A., "La Guerra Con Mexico Y Los Disidentes Estadunidenses, 1846-1848" [The War with Mexico and US Dissenters, 1846-48]. Secuencia [Mexico] 2004 (59): 32–70. Issn: 0186-0348

- Reséndez, Andrés. Changing National Identities at the Frontier: Texas and New Mexico, 1800-1850 (2004) excerpt and text search

- Rives, George L. "Mexican Diplomacy on the Eve of War with the United States," The American Historical Review Vol. 18, No. 2 (Jan., 1913), pp. 275–294 in JSTOR

- Robinson, Cecil, The View From Chapultepec: Mexican Writers on the Mexican War, (1989)

- Rodríguez Díaz, María Del Rosario. "Mexico's Vision of Manifest Destiny During the 1847 War" Journal of Popular Culture 2001 35(2): 41–50. Issn: 0022-3840

- Ruiz, Ramon Eduardo. Triumph and Tragedy: A History of the Mexican People, (1992) ch 5 pp 205–19; excerpt and text search

- Ruiz, Vicki L. "Nuestra America: Latino History as United States History." Journal of American History 2006 93(3): 655–672. Issn: 0021-8723 Fulltext: History Cooperative

- Sears, Louis Martin. "Nicholas P. Trist, A Diplomat with Ideals," The Mississippi Valley Historical Review Vol. 11, No. 1 (Jun., 1924), pp. 85–98 in JSTOR

- Smith, Justin H. "American Rule in Mexico," The American Historical Review Vol. 23, No. 2 (Jan., 1918), pp. 287–302 in JSTOR

Primary Sources[edit]

- Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant

- Laidley, Theodore. Surrounded by Dangers of All Kinds: The Mexican War Letters of Lieutenant Theodore Laidley (1997) excerpt and text search

- Polk, James K. The Diary of James K. Polk During His Presidency, 1845-1849 edited by Milo Milton Quaife, 4 vols. 1910. complete text vol. 1; complete text vol. 2; complete text vol. 3; complete text vol 4; also Abridged version by Allan Nevins. 1929, online

- Ramírez, José Fernando. Mexico during the War with the United States. (1950), 165pp, firsthand account of life in Mexico City during the war.

Notes[edit]

- ↑ http://www.historyguy.com/Mexican-American_War.html

- ↑ See Reséndez, Changing National Identities at the Frontier: Texas and New Mexico, 1800-1850 (2004). "A few, very few, packed up their belongings and trekked south to land still held by Mexico, according to Julian Samora and Patricia Vandel Simon, A History of the Mexican-American People (1977) p 100

- ↑ The Aftermath of War

- ↑ The El Paso Salt War

- ↑ Donald Fithian Stevens, Origins of Instability in Early Republican Mexico (1991) p. 11

- ↑ Miguel E. Soto, "The Monarchist Conspiracy and the Mexican War" in Essays on the Mexican War ed by Wayne Cutler (1986). pp 66-67

- ↑ Bauer, K. Jack "The Mexican-American War 1846-48"

- ↑ The Battle of Buena Vista

- ↑ See Robert S. Chamberlain, ed. "Letter of Antonio López de Santa Anna to Manuel Reyes Veramendi, President of the Ayuntamiento of Mexico City, Guadalupe, September 15, 1847," The Hispanic American Historical Review Vol. 24, No. 4 (Nov., 1944), pp. 614-617 in JSTOR

- ↑ Joseph G. Dawson III, "Leaders for Manifest Destiny: American Volunteer Colonels Serving in the U.S.-Mexican War." American Nineteenth Century History (2006) 7(2): 253-279. Issn: 1466-4658 Fulltext: Ebsco

- ↑ Kevin Dougherty, Civil War Leadership and Mexican War Experience (2007)

- ↑ Congressional Globe, 30th Session (1848) pp.93-95

- ↑ His attacks were also held against him when he applied for a patronage job in the new Taylor administration. Albert J. Beveridge, . Abraham Lincoln, 1809-1858 (1928) 1: 428-33; David Donald, Lincoln (1995) pp. 140-43.

- ↑ The Mexican War by David Saville Muzzey, Ph.D. (IN: An American History, by David Saville Muzzey. Boston : Ginn Company, 1911)

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20050405030126/http://www.musketoon.com/2005/02/battle-of-santa-cruz-de-rosales-16.html

- ↑ Nunis, D.B., editor, The Mexican War in Baja California, 1977, Los Angeles: Dawson's Book Shop

- ↑ Apuntes' and the Lessons of History.

- ↑ Foos (2002) p 85

Categories: [Mexican History] [United States History] [Wars]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 01:22:00 | 40 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Mexican-American_War | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF