Ordovician

From Nwe

From Nwe | Paleozoic era (542 - 251 mya) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cambrian | Ordovician | Silurian | Devonian | Carboniferous | Permian |

The Ordovician period is an interval of about 44 million years defined on the geologic timescale as spanning roughly from 488 to 444 million years ago (mya) and being noteworthy for both beginning and ending with extinction events, while also being a source of abundant fossils and in some regions major reservoirs of oil and gas. It is the second of six periods of the Paleozoic era, lying between the earlier Cambrian period and the later Silurian period.

In the seas, which covered much of the continental land mass, one prominent form of life was the cephalopods, a group of mollusks related to the squid and octopus, while trilobites and brachipods (looking externally somewhat similar to clams) were common, and diverse other invertebrate forms complemented the widespread sponges and corals as red and green algae floated in the water. The chordates were represented by the ostrachoderms, an early jawless fish.

The extinction event marking the beginning of the Ordovician period is considered a minor one, but the Ordovician-Silurian extinction event, which ends the period, wiped out about 60 percent of marine genera. Geophysical indicators for the period are consistent with the faunal extinction record.

Global average temperature held fairly constant through more than the first half of the period, but declined precipitously toward the end of the period as an interval marked by glaciation began. Sea level was significantly higher than today when the period began and it rose even higher through more than the first half of the period before dropping some 80 meters (263 feet) toward the end of the period as ice accumulated on the land. The Ordovician atmosphere had about 70 percent as much oxygen and about 1500 percent as much carbon dioxide as today's atmosphere.

The Ordovician, named after the Welsh tribe of the Ordovices, was defined by Charles Lapworth, in 1879, to resolve a dispute between followers of Adam Sedgwick and Roderick Murchison, who were placing the same rock beds in northern Wales into the Cambrian and Silurian periods, respectively. Recognizing that the fossil fauna in the disputed strata were different from those of either the Cambrian or the Silurian periods, Lapworth placed them in a period of their own.

Ordovician subdivisions

After Charles Lapworth first defined the Ordovician period in 1879 in the United Kingdom, other areas of the world accepted it quickly, while its acceptance came last to the United Kingdom. The Ordovician period received international sanction in 1906, when it was adopted as an official period of the Paleozoic era by the International Geological Congress. Further elaboration of the fossil evidence provided the basis for subdividing the period.

The Ordovician Period is usually broken into Early (Tremadoc and Arenig), Middle (Llanvirn, subdivided into Abereiddian and Llandeilian), and Late (Caradoc and Ashgill) epochs. The corresponding rocks of the Ordovician System are referred to as coming from the Lower, Middle, or Upper part of the column. The faunal stages (subdivisions based on fossil evidence) from youngest to oldest are:

- Late Ordovician: Ashgill epoch

- Hirnantian/Gamach

- Rawtheyan/Richmond

- Cautleyan/Richmond

- Pusgillian/Maysville/Richmond

- Middle Ordovician: Caradoc epoch

- Trenton

- Onnian/Maysville/Eden

- Actonian/Eden

- Marshbrookian/Sherman

- Longvillian/Sherman

- Soundleyan/Kirkfield

- Harnagian/Rockland

- Costonian/Black River

- Middle Ordovician: Llandeilo epoch

- Chazy

- Llandeilo

- Whiterock

- Llanvirn

- Early Ordovician: Arenig epoch

- Cassinian

- Arenig/Jefferson/Castleman

- Tremadoc/Deming/Gaconadian

Ordovician paleogeography

Sea levels were high during the Ordovician period, ranging from 180 meters (590 feet) above modern sea level at the beginning to a peak in the late Ordovician of 220m (722ft) and then falling rapidly near the end of the period to 140m (459ft) (Huq 2008). Coincident with the drop in sea level was drop in the global mean temperature of nearly 10 degrees Celsius (18 degrees Fahrenheit).

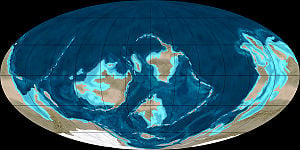

During the Ordovician, the southern continents were collected into a single continent called Gondwana. Gondwana started the period in equatorial latitudes and, as the period progressed, drifted toward the South Pole. As with North America and Europe, Gondwana was largely covered with shallow seas during the Ordovician. Shallow clear waters over continental shelves encouraged the growth of organisms that deposit calcium carbonates in their shells and hard parts. Panthalassic Ocean covered much of the northern hemisphere, and other minor oceans included Proto-Tethys, Paleo-Tethys, Khanty Ocean (which was closed off by the Late Ordovician), Iapetus Ocean, and the new Rheic Ocean. By the end of the period, Gondwana had neared or approached the pole and was largely glaciated.

The Early Ordovician was thought to be quite warm, at least in the tropics.

Ordovician rocks are chiefly sedimentary. Because of the restricted area and low elevation of solid land, which set limits to erosion, marine sediments that make up a large part of the Ordovician system consist chiefly of limestone. Shale and sandstone are less conspicuous.

A major mountain-building episode was the Taconic orogeny, which had gotten well under way in Cambrian times and continued into the Ordovician period.

Ordovician life

Ordovician fauna

In what was to become North America and Europe, the Ordovician period was a time of shallow continental seas rich in life. Trilobites and brachiopods in particular were numerous and diverse. The world's largest trilobite, Isotelus rex, was found in 1998, by Canadian scientists in Ordovician rocks on the shores of Hudson Bay. The first bryozoa appeared in the Ordovician as did the first coral reefs—although solitary corals dating back to at least the Cambrian have been found. Mollusks, which had also appeared during the Cambrian, became common and varied, especially bivalves, gastropods, and nautiloid cephalopods.

It was long thought that the first true chordates appeared in the Ordovician period in the form of fossils of the fish-like Ostracoderms found in strata traced to the Middle Ordovician (Gregory 1935). More recently, however, fossils of other fish-like creatures, the 530-million-year-old Early Cambrian fossil dubbed Haikouella and then the 515-million-year-old middle Cambrian animal Pikaia have been promoted as the world's earliest chordate (Heeren 2000).

The very first jawed fish appeared in the Late Ordovician epoch and now-extinct worm-shaped marine animals called graptolites thrived in the oceans. Some cystoids (primitive stalked marine animals related to modern starfish and sand dollars) and crinoids (called sea lilies and feather stars; also related to starfish and sand dollars) appeared.

Ordovician flora

Green algae were common in the Ordovician and Late Cambrian (perhaps earlier). Plants probably evolved from green algae. The first terrestrial plants appeared in the form of tiny plants resembling liverworts. Fossil spores from land plants have been identified in uppermost Ordovician sediments.

Fungal life

The first land fungi probably appeared in the Latest Ordovician, following the appearance of plants. Marine fungi were abundant in the Ordovician seas, apparently decomposing animal carcasses, and other wastes.

End of the Ordovician

- Main article: Ordovician-Silurian extinction events.

The Ordovician period came to a close in a series of extinction events that, taken together, comprise the second largest of the five major extinction events in Earth's history in terms of percentage of genera that went extinct. The only larger one was the Permian-Triassic extinction event.

The extinctions occurred approximately 444-447 million years ago and mark the boundary between the Ordovician and the following Silurian Period. At that time, all complex multicellular organisms lived in the sea, and about 49 percent of genera of fauna disappeared forever; brachiopods and bryozoans were decimated, along with many of the trilobite, conodont, and graptolite families.

Melott et al. (2006) have suggested a ten-second gamma ray burst could have been responsible, destroying the ozone layer and exposing terrestrial and marine surface-dwelling life to radiation. Most scientists continue to agree that extinction events are complex events with multiple causes.

The most commonly accepted theory is that these extinction events were triggered by the onset of an ice age, in the Hirnantian faunal stage that ended the long, stable greenhouse conditions typical of the Ordovician. The ice age was probably not as long-lasting as once thought; study of oxygen isotopes in fossil brachiopods shows that it was probably no longer than 0.5 to 1.5 million years (Stanley 1999). The event seemingly was preceded by a fall in atmospheric carbon dioxide (from 7000 ppm to 4400 ppm), which selectively affected the shallow seas where most organisms lived. As the southern supercontinent Gondwana drifted over the South Pole, ice caps formed on it, which have been detected in Upper Ordovician rock strata of North Africa and then-adjacent northeastern South America, which were south-polar locations at the time.

Glaciation locks up water from the ocean, and the interglacials free it, causing sea levels repeatedly to drop and rise. The vast shallow intra-continental Ordovician seas withdrew, which eliminated many ecological niches. It then returned carrying diminished founder populations lacking many whole families of organisms, then withdrew again with the next pulse of glaciation, eliminating biological diversity at each change (Emiliani 1992). Species limited to a single epicontinental sea on a given landmass were severely affected (Stanley 1999). Tropical lifeforms were hit particularly hard in the first wave of extinction, while cool-water species were hit worst in the second pulse (Stanley 1999).

Surviving species were those that coped with the changed conditions and filled the ecological niches left by the extinctions.

At the end of the second event, it is speculated that melting glaciers caused the sea level to rise and stabilize once more. The rebound of life's diversity with the permanent re-flooding of continental shelves at the onset of the Silurian saw increased biodiversity within the surviving orders.

Notes

- ↑ Wellman, C.H., Gray, J. (2000). The microfossil record of early land plants. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 355 (1398): 717–732.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Gregory, W. K. “On the evolution of the skulls of vertebrates with special reference to heritable changes in proportional diameters (anisomerism).” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 21(1):1-8, 1935.

- Heeren, F. Challenging fossil of a little fish The Boston Globe. May 30, 2000. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- Huq, B.U. "A Chronology of Paleozoic Sea-Level Changes." Science 322: 64-68, 2008.

- International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- Melott, A., et al. Did a gamma-ray burst initiate the late Ordovician mass extinction? International Journal of Astrobiology 3:55, 2004.

- Ogg, J. Overview of Global Boundary Stratotype Sections and Points (GSSP's). 2004. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- Stanley, S. M. Earth System History. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company, 1999. ISBN 0-7167-2882-6.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 00:31:45 | 30 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Ordovician | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF