Mongolia

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia | Монгол улс Mongol uls | |

|---|---|

| Flag | Coat of Arms |

| Capital | Ulaanbaatar |

| Government | Parliamentary republic |

| Language | Mongolian (official) |

| President | Tsakhia Elbegdorj |

| Prime minister | Chimed Saikhanbileg |

| Area | 603,909 sq mi |

| Population | 3,300,000 (2020) |

| GDP 2005 | $5.56 billion |

| GDP per capita | $2,175 |

| Currency | Tögrög |

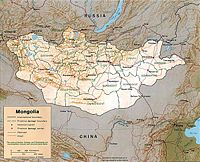

Mongolia is a country in northeast Asia, bordering China, Russia, and with a tiny border to Kazakhstan. The country's population estimate in 2002 was 2,694,432, and Mongolia's capital is Ulaanbaatar (sometimes spelled "Ulan Bator"). Ulaanbaatar is also home to a large portion of the thinly-populated country's citizens, with a metropolitan area population of approximately 900,000. Other prominent cities in Mongolia include Darkhan (meaning "smithy" or "blacksmith") which was a city created as a model town under Mongolia's communist rule, with a population of 95,500, and Choibalsan, with a population 47,000. At 1,564,116 square kilometres, Mongolia is the nineteenth largest country in the world, but also the least densely populated nation on earth, with an average of 1.7 persons per square kilometer. After Kazakhstan, Mongolia is the second largest land-locked country on earth.

People[edit]

Life in sparsely populated Mongolia has recently become more urbanized. Nearly half of the people live in the capital, Ulaanbaatar, and in other provincial centers. Semi-nomadic life still predominates in the countryside, but settled agricultural communities are becoming more common. Mongolia's birth rate is estimated at 19 births/1000 people (2006). About two-thirds of the total population is under age 30, 28.5% of whom are under 14.

Ethnic Mongols account for about 85% of Mongolia's population and consist of Khalkha and other groups, all distinguished primarily by dialects of the Mongol language. Mongol is an Altaic language—from the Altaic Mountains of Central Asia, a language family comprising the Turkic, Tungusic, and Mongolic subfamilies—and is related to Turkic (Uzbek, Turkish, and Kazakh), Korean, and, possibly, Japanese. Among ethnic Mongols, the Khalkha comprise 90% and the remaining 10% include Durbet Mongols in the north and Dariganga Mongols in the east. Turkic speakers (Kazakhs, Turvins, and Khotans) constitute 7% of Mongolia's population, and the rest are Tungusic-speakers, Chinese, and Russians. Most Russians left the country following the withdrawal of economic aid and collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Religion[edit]

Traditionally, Tibetan Buddhist Lamaism was the predominant religion. However, it was suppressed under the communist regime until 1990, with only one showcase monastery allowed to remain. Since 1990, as liberalization began, Buddhism has enjoyed a resurgence. Mongolia also has a number of minority religions, including Tengrism and Pi Shashin. About 4 million ethnic Mongols live outside Mongolia; about 3.4 million live in China, mainly in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, and some 500,000 live in Russia, primarily in Buryatia and Kalmykia.

Government and Political Conditions[edit]

Until 1990, the Mongolian Government was modeled on the Soviet system; only the communist party—the MPRP—officially was permitted to function. After some instability during the first two decades of communist rule in Mongolia, there was no significant popular unrest until December 1989. Collectivization of animal husbandry, introduction of agriculture, and the extension of fixed abodes were all carried out without perceptible popular opposition.

The birth of perestroika in the former Soviet Union and the democracy movement in Eastern Europe were mirrored in Mongolia. The dramatic shift toward reform started in early 1990 when the first organized opposition group, the Mongolian Democratic Union, appeared. In the face of extended street protests in subzero weather and popular demands for faster reform, the politburo of the MPRP resigned in March 1990. In May, the constitution was amended, deleting reference to the MPRP's role as the guiding force in the country, legalizing opposition parties, creating a standing legislative body, and establishing the office of president.

Mongolia's first multi-party elections for a People's Great Hural were held on July 29, 1990. The MPRP won 85% of the seats. The People's Great Hural first met on September 3 and elected a president (MPRP), vice president (SDP—Social Democrats), prime minister (MPRP), and 50 members to the Baga Hural (small Hural). The vice president also was chairman of the Baga Hural. In November 1991, the People's Great Hural began discussion on a new constitution, which entered into force February 12. In addition to establishing Mongolia as an independent, sovereign republic and guaranteeing a number of rights and freedoms, the new constitution restructured the legislative branch of government, creating a unicameral legislature, the State Great Hural (SGH).

The 1992 constitution provided that the president would be elected by popular vote rather than by the legislature as before. In June 1993, incumbent Punsalmaagiyn Ochirbat won the first popular presidential election running as the candidate of the democratic opposition.

As the supreme government organ, the SGH is empowered to enact and amend laws, determine domestic and foreign policy, ratify international agreements, and declare a state of emergency. The SGH meets semiannually for 3-4 month sessions. SGH members elect a chairman and vice chairman who serve 4-year terms. SGH members are popularly elected by district for 4-year terms.

The president is the head of state, commander in chief of the armed forces, and head of the National Security Council. He is popularly elected by a national majority for a 4-year term and limited to two terms. The constitution empowers the president to propose a prime minister, call for the government's dissolution in consultation with the SGH chairman, initiate legislation, veto all or parts of legislation (the SGH can override the veto with a two-thirds majority), and issue decrees, which become effective with the prime minister's signature. In the absence, incapacity, or resignation of the president, the SGH chairman exercises presidential power until inauguration of a newly elected president.

The government, headed by the prime minister, has a 4-year term. The prime minister is nominated by the president and confirmed by the SGH. Under constitutional changes made in 2001, the president is required to nominate the prime ministerial candidate proposed by a party or coalition with a majority of members of the SGH. The prime minister chooses a cabinet, subject to SGH approval. Dissolution of the government occurs upon the prime minister's resignation, simultaneous resignation of half the cabinet, or after an SGH vote for dissolution.

Local hurals are elected by the 21 aimags (provinces) plus the capital, Ulaanbaatar. On the next lower administrative level, they are elected by provincial subdivisions and urban subdistricts in Ulaanbaatar and all aimags.

Political Parties[edit]

- Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party

- Democratic Party

- Motherland-Mongolian Democratic New Socialist Party

- National New Party

- Civil Will Party

- Mongolian People's Party

- Mongolian Green Party

- Mongolian Traditional United Party

- Mongolian National Solidarity Party

- Mongolian Liberal Democratic Party

- Mongolian Republican Party

- Mongolian Women’s National United Party

- Mongolian Liberal Party

- Mongolian Social Democratic Party

- Freedom Implementing Party

Legal System[edit]

The 1992 constitution empowered a General Council of Courts (GCC) to select all judges and protect their rights. The Supreme Court is the highest judicial body. Justices are nominated by the GCC and confirmed by the SGH and president. The court is constitutionally empowered to examine all lower court decisions—excluding specialized court rulings—upon appeal and provide official interpretations on all laws except the constitution.

Specialized civil, criminal, and administrative courts exist at all levels and are not subject to Supreme Court supervision. Local authorities—district and city governors—ensure that these courts abide by presidential decrees and SGH decisions. At the apex of the judicial system is the Constitutional Court, which consists of nine members, including a chairman, appointed for 6-year terms, whose jurisdiction extends solely over the interpretation of the constitution.

Principal Government Officials[edit]

- President—Tsakhia Elbegdorj

- Prime Minister—Chimed Saikhanbileg

Foreign Relations[edit]

In the wake of the international socialist economic system's collapse and the disintegration of the former Soviet Union, Mongolians began to pursue an independent and nonaligned foreign policy. Mongolia is landlocked between Russia and China, and seeks cordial relations with both nations. At the same time, Mongolia has sought to advance its regional and global relations. Ties with Japan and South Korea are particularly strong. Japan is the largest bilateral aid donor to Mongolia, a position it has held since 1991. Mongolia has also made efforts to steadily boost ties with European countries.

As part of its aim to establish a more balanced nonaligned foreign policy, Mongolia has sought to take a more active role in the United Nations and other international organizations, and has pursued a more active role in Asian and northeast Asian affairs. Mongolia became a full participant in the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) in July 1998 and a full member of the Pacific Economic Cooperation Council in April 2000. Mongolia is currently seeking to join the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum (APEC). Mongolia is an observer in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, but has stated it does not intend to seek membership.

Mongolian relations with China began to improve in the mid-1980s when consular agreements were reached and cross-border trade contacts expanded. In May 1990, a Mongolian head of state visited China for the first time in 28 years. The cornerstone of the Mongolian-Chinese relationship is a 1994 Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation, which codifies mutual respect for the independence and territorial integrity of both sides. China has objected strongly to the five visits since 1990 of the Dalai Lama; during the last, in 2002, China briefly disrupted railroad links for "technical" reasons. There are regular high-level visits and expanding trade ties. President Hu Jintao visited Mongolia in 2003. President Bagabandi visited China in 2004, and President Enkhbayar visited in 2005.

After the disintegration of the former Soviet Union, Mongolia developed relations with the new independent states. Links with Russia and other republics were essential to contribute to stabilization of the Mongolian economy. In 1991, Mongolia and Russia concluded both a Joint Declaration of Cooperation and a bilateral trade agreement. This was followed by a 1993 Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation establishing a new basis of equality in the relationship. Mongolian President Bagabandi visited Moscow in 1999, and Russian President Vladimir Putin visited Mongolia in 2000 in order to sign the 25-point Ulaanbaatar Declaration, reaffirming Mongol-Russian friendship and cooperation on numerous economic and political issues. In December 2003, Mongolia finally settled the Soviet-era debt it owed to Russia with a negotiated payment of $250 million. In July 2006, Prime Minister Fradkov visited Mongolia with a large business delegation. The Mongolian and Russian Governments continue to jointly own the railroad and the large Erdenet copper mine. President Enkhbayar visited Moscow in December 2006.

Economy[edit]

Economic activity in Mongolia has traditionally been based on herding and agriculture. Mongolia has extensive mineral deposits; copper, coal, molybdenum, tin, tungsten, and gold account for a large part of industrial production. Soviet assistance, at its height one-third of GDP, disappeared almost overnight in 1990-91 at the time of the dismantlement of the U.S.S.R., leading to a very deep recession. Economic growth returned due to reform embracing free-market economics and extensive privatization of the formerly state-run economy. Severe winters and summer droughts in 2000-2001 and 2001-2002 resulted in massive livestock die-off and anemic GDP growth of 1.1% in 2000 and 1% in 2001. This was compounded by falling prices for Mongolia’s primary-sector exports and widespread opposition to privatization. Growth improved to 4% in 2002, 5% in 2003, 10.6% in 2004, 6.2% in 2005 and 7.5% in 2006. Much of the growth was due to high copper prices and new gold production. Other than agriculture (20.2% of GDP), dominant industries in the composition of GDP are mining 20.4%, trade and service 24.8% and transportation, storage, and communication 12.2%. Mongolia’s economy continues to be heavily influenced by its neighbors. For example, Mongolia purchases 80% of its petroleum products from Russia. China is Mongolia’s chief export partner and a main source of the “shadow,” or “gray” economy. The gray economy is estimated to be at least one-third the size of the official economy. The actual size of this gray—largely cash—economy is difficult to calculate since the money does not pass through the hands of tax authorities or the banking sector. Remittances from Mongolians working abroad, both legally and illegally, constitute a sizeable portion. Money laundering is growing as an accompanying concern. Mongolia settled its large debt to Russia at the end of 2003 on favorable terms. Mongolia, which joined the World Trade Organization in 1997, is the only member of that organization to not be a participant in a regional trade organization. Mongolia seeks to expand its participation and integration into Asian regional economic and trade regimes.

Because of Mongolia's remoteness and natural beauty, the tourism sector has recently shown signs of rapid growth. With spiking international commodity prices, there has been a surge of international interest in investing in Mongolia’s minerals sector despite the absence of a policy environment firmly conducive to private investment. How effectively Mongolia mobilizes private international investment around its comparative advantages (mineral wealth, small population, and proximity to China and its burgeoning markets) will ultimately determine its success in sustaining rapid economic growth. Parliament passed a windfall profits tax on copper and gold that took effect in mid-2006, and major amendments to the minerals law allowing the government to take an equity stake in major new mines. It is unknown what effect these laws will have on mining activities in Mongolia, although major potential investors expressed considerable concern about the changes.

Parliament in 2006 passed four new tax laws: personal and corporate income, value-added and excise, intended to reduce the overall tax burden on taxpayers and stimulate the economy. Most provisions of the new laws took effect January 1, 2007. No projections of the economic effects are currently available.

Environment[edit]

As a result of rapid urbanization and industrial growth policies under the communist regime, Mongolia's deteriorating environment has become a major concern. The burning of soft coal by individual home or “ger” (yurt in Russian) owners, power plants, and factories in Ulaanbaatar has resulted in severely polluted air. Deforestation, overgrazed pastures, and efforts to increase grain and hay production by plowing up more virgin land have increased soil erosion from wind and rain. With the rapid growth of newly privatized herds, overgrazing in selected areas also is a concern. Recent rapid and relatively unregulated growth in the mining sector for minerals (gold, coal, etc.) has become the focus of public debate. A great deal of public attention is being paid to non-transparency of the government process of awarding licenses, the equitable sharing of economic rents between foreign investors and the Government of Mongolia, and the potential impact on the environment. However, the real environmental concern is the sharp boom in the number of informal gold miners, who frequently illegally use mercury, which may lead to an epidemic of mercury poisoning.

History[edit]

In 1206 AD, a single Mongolian state was formed based on nomadic tribal groupings under the leadership of Chinggis ("Genghis") Khan. He and his immediate successors conquered nearly all of Asia and European Russia and sent armies as far as central Europe and Southeast Asia. Chinggis Khan's grandson Kublai Khan, who conquered China and established the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368 AD), gained fame in Europe through the writings of Marco Polo.

Although Mongol-led confederations sometimes exercised wide political power over their conquered territories, their strength declined rapidly after the Mongol dynasty in China was overthrown in 1368. The Manchus, a tribal group which conquered China in 1644 and formed the Qing dynasty, were able to bring Mongolia under Manchu control in 1691 as Outer Mongolia when the Khalkha Mongol nobles swore an oath of allegiance to the Manchu emperor. The Mongol rulers of Outer Mongolia enjoyed considerable autonomy under the Manchus, and all Chinese claims to Outer Mongolia following the establishment of the republic have rested on this oath. In 1727, Russia and Manchu China concluded the Treaty of Khiakta, delimiting the border between China and Mongolia that exists in large part today.

Outer Mongolia was a Chinese province (1691-1911), an autonomous state under Russian protection (1912–19), and again a Chinese province (1919–21). As Manchu authority in China waned, and as Russia and Japan confronted each other, Russia gave arms and diplomatic support to nationalists among the Mongol religious leaders and nobles. The Mongols accepted Russian aid and proclaimed their independence of Chinese rule in 1911, shortly after a successful Chinese revolt against the Manchus. By agreements signed in 1913 and 1915, the Russian Government forced the new Chinese Republican Government to accept Mongolian autonomy under continued Chinese control, presumably to discourage other foreign powers from approaching a newly independent Mongolian state that might seek support from as many foreign sources as possible.

The Russian revolution and civil war afforded Chinese warlords an opportunity to re-establish their rule in Outer Mongolia, and Chinese troops were dispatched there in 1919. Following Soviet military victories over White Russian forces in the early 1920s and the occupation of the Mongolian capital Urga in July 1921, Moscow again became the major outside influence on Mongolia. The Mongolian People's Republic was proclaimed on November 25, 1924.

Between 1925 and 1928, power under the communist regime was consolidated by the Mongolian Peoples Revolutionary Party (MPRP). The MPRP left gradually undermined rightist elements, seizing control of the party and the government. Several factors characterized the country during this period: The society was predominantly nomadic and illiterate; there was no industrial proletariat; the aristocracy and the religious establishment shared the country's wealth; there was widespread popular obedience to traditional authorities; the party lacked grassroots support; and the government had little organization or experience.

In an effort at swift socioeconomic reform, the leftist government applied extreme measures that attacked the two most dominant institutions in the country—the aristocracy and the religious establishment. Between 1932 and 1945, their excess zeal, intolerance, and inexperience led to anti-communist uprisings. In the late 1930s, purges directed at the religious institution resulted in the desecration of hundreds of Buddhist institutions and imprisonment of more than 10,000 people.

Sovietization[edit]

During the Russian Civil War immediately after the Bolshevik Revolution, parts of the White Army fled into Mongolia. The Soviet Red Army was sent there and remained until 1925. Mongolia was transformed into a Russian dependency and was the first country outside of the Soviet Union to become an actual part of the Soviet zone of occupation. It remained a Chinese province but a Soviet dependency.[1][2]

In January 1935, Soviet troops entered Mongolia. On March 12, 1936, an agreement with a Soviet puppet regime was signed. The Soviet Union ignored Chinese protests. In 1936 military expenditures were doubled, and by 1938 more than half of Mongolia's budget was for defense. Economic planning was implemented. By 1939 Choybalsan had emerged as the premier, the minister of war, and the undisputed leader of Mongolia. During World War II the Mongolian Army numbered between 80,000 and 100,000 troops, a huge percentage of the total population of 900,000.

An antireligious campaign continued slowly but relentlessly. Emphasis was placed on ideological warfare. Political commissars were attached to monasteries, construction of new monasteries was forbidden by law, the enrollment of minors was disallowed, and monks became eligible for military service. Many monasteries were destroyed; others were expropriated by the Communist regime. Suppression became especially bloody in the second half of the 1930s. In 1937 and 1938, about 2,000 of monks were executed. Thousands were arrested and jailed. The financially shattered monasteries gradually were closed in the period 1938 to 1939. The campaign against the Buddhists was largely successful. Within two decades, the resident monastic population was reduced from about 15,000 to approximately 200 monks.

There also were renewed purges in the inner party ranks in 1937 to 1939. Uncooperative political leaders were accused of aiding the Japanese. One after the other, many top party and government officials fell from power and were executed or were imprisoned.

Soviets vs Japan[edit]

In 1938, Soviet and Japanese fought many skirmishes across the common border their troops occupied along the Manchurian and Mongolian frontiers. Skirmishes, beginning in 1939, gradually grew into open warfare by May 1939 with Japanese forces based in Manchukuo. That summer a Japanese army invaded eastern Mongolia. Soviet General Georgi Zhukov commanded the Soviet-Mongolian army that met this invasion. In a battle at Khalkhin-Gol (also Khalkhyn Gol) on 20 August, the Soviets threw the Japanese back across the Manchurian border.[3] The Japanese may have sustained as many as 80,000 casualties compared with 11,130 on the Comintern side. Hostilities ended on September 16, 1939. The Soviet Union and Japan signed a truce, and a commission was set up to define the Mongolian-Manchurian border. Although Japan did not invade again, it did mass large military forces along the Mongolian and the Soviet borders in the course of the war, while continuing its southward drive into China.

World War II[edit]

The Soviet position in Mongolia was now fully consolidated. Throughout World War II, Choybalsan followed Moscow's directives, livestock, raw materials, money, food, and military clothing were taken from Mongolia to the Soviet Union. During World War II, because of a growing Japanese threat over the Mongolian-Manchurian border, the Soviet Union reversed the course of Mongolian socialism in favor of a new policy of economic gradualism and buildup of the national defense. The Soviet-Mongolian army defeated Japanese forces that had invaded eastern Mongolia in the summer of 1939, and a truce was signed setting up a commission to define the Mongolian-Manchurian border in the autumn of that year.

Cold War[edit]

During the Cold War, Moscow reasserted its influence in Mongolia. Secure in its relations with Moscow, the Mongolian Government shifted to postwar development, focusing on civilian enterprise. International ties were expanded, and Mongolia established relations with North Korea and the new communist governments in Eastern Europe. It also increased its participation in communist-sponsored conferences and international organizations. Mongolia became a member of the United Nations in 1961.

After Nikita Khrushchev's 1956 condemnation of some of Joseph Stalin's crimes, the Mongolian People's Republic, following in the footsteps of the 'fraternal' Soviet Union, also succumbed to the 'thaw.' Khrushchev used de-Stalinization to discredit his hard-line opponents. Mongolia's leader, Yumjaagiyn Tsedenbal, was a Stalin-era holdover who came under criticism from his rivals for being unenthusiastic about political reforms. Tsedenbal had good reason to downplay de-Stalinization; he shared responsibility with Marshal Horloogiyn Choibalsan for violent repressions in the 1940s. But Tsedenbal outmaneuvered and eliminated his opponents in the late 1950s and early 1960s and consolidated his grip on power by 1964. Toward the end of that year, however, Tsedenbal once again was challenged, this time from an unexpected direction. Several members of the Central Committee of the Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party (MPRP) used the precedent of Khrushchev's forced retirement from his leadership posts in Moscow in October 1964 as a pretext to overthrow Tsedenbal. At a plenum of the MPRP Central Committee in December 1964, Tsedenbal was accused of incompetence, corruption, disrespect for principles of 'Party democracy,' lack of economic discipline, and overreliance on the Soviet Union for credits. But Tsedenbal rebuffed the 'anti-Party group' and depicted the affair as an attempted coup engineered by pro-Chinese sympathizers and spies. Soviet leaders were wary of Chinese efforts to 'subvert' Moscow's influence in the socialist camp and were therefore willing to endorse Tsedenbal's version of events.[4]

Tensions with China[edit]

In the early 1960s, Mongolia attempted to maintain a neutral position amidst increasingly contentious Sino-Soviet polemics; this orientation changed in the middle of the decade. Mongolia and the Soviet Union signed an agreement in 1966 that introduced large-scale Soviet ground forces as part of Moscow's general buildup along the Sino-Soviet frontier.

During the period of Sino-Soviet tensions, relations between Mongolia and China deteriorated. In 1983, Mongolia systematically began expelling some of the 7,000 ethnic Chinese in Mongolia to China. Many of them had lived in Mongolia since the 1950s, when they were sent there to assist in construction projects.

Democracy[edit]

In the years after 1990, Mongolia became a multi-party democracy, which—in contrast to the almost previous 70 years—actively sought ties with western countries, especially the US.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ While You Slept : Our Tragedy in Asia and Who Made It, John T. Flynn, New York : The Devin - Adair Company, 1951, pg. 16 pdf.

- ↑ Rival Government: Mongolian Revolutionary Provisional Government. Retrieved from worldstatemen.org September 24, 2007.

- ↑ Jerrold and Leona Schecter, Sacred Secrets: How Soviet Intelligence Operations Changed American History, Washington, DC: Brassey’s, 2002, pg. 10.

- ↑ Sergey S. Radchenko, "Mongolian Politics in the Shadow of the Cold War: the 1964 Coup Attempt and the Sino-soviet Split," Journal of Cold War Studies 2006 8(1): 95-119,

| Copyright Details | |

|---|---|

| License: | This work is in the Public Domain in the United States because it is a work of the United States Federal Government under the terms of Title 17, Chapter 1, Section 105 of the U.S. Code |

| Source: | File available from the United States Federal Government. |

Source =Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Categories: [Landlocked Countries] [Buddhism]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/28/2023 12:44:44 | 189 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Mongolia | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF