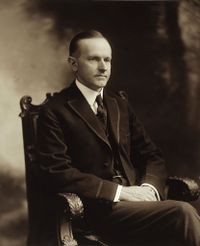

Calvin Coolidge

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia | Calvin Coolidge | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| 30th President of the United States From: August 2, 1923 – March 4, 1929 | |||

| Vice President | Charles G. Dawes (1925–1929) | ||

| Predecessor | Warren G. Harding | ||

| Successor | Herbert Hoover | ||

| 29th Vice President of the United States From: March 4, 1921 – August 2, 1923 | |||

| President | Warren G. Harding | ||

| Predecessor | Thomas R. Marshall | ||

| Successor | Charles G. Dawes | ||

| 48th Governor of Massachusetts From: January 2, 1919 – January 6, 1921 | |||

| Lieutenant | Channing H. Cox | ||

| Predecessor | Samuel W. McCall | ||

| Successor | Channing H. Cox | ||

| 46th Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts From: January 6, 1916 – January 2, 1919 | |||

| Governor | Samuel W. McCall | ||

| Predecessor | Grafton D. Cushing | ||

| Successor | Channing H. Cox | ||

| 16th Mayor of Northampton, Massachusetts From: 1910-1911 | |||

| Predecessor | James W. O'Brien | ||

| Successor | William Feiker | ||

| Information | |||

| Party | Republican | ||

| Spouse(s) | Grace Goodhue Coolidge | ||

| Religion | Congregationalist | ||

John Calvin Coolidge, Jr. (July 4, 1872 - January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States of America from 1923 to 1929, an era of peace and prosperity. He was elected vice president in 1920 as a Republican and took office in August 1923 upon the death of President Warren G. Harding; he was reelected by a landslide in 1924, but in 1928 at the peak of his popularity he announced in typical laconic fashion that he did not choose to run again.

Coolidge was so frugal that throughout the peak of his political career, including while he was president, he lived in a cramped duplex in western Massachusetts which he did not even own, and in which another family lived in the other half.

Contents

Early career[edit]

Coolidge was born in Plymouth, Vermont, July 4, 1872, the son of John and Victoria Moor Coolidge. Both parents were Yankees; his ancestors came from England to New England in the early seventeenth century. Coolidge's father was a farmer and a successful country storekeeper who dabbled in local and state politics. Young Calvin was educated in the local school and later at Black River and St. Johnsbury academies. In 1891 he entered Amherst College in Massachusetts, where he showed an interest in philosophy. Reserved and reticent, he did not mix readily with his fellows. In his senior year, however, he was selected as class speaker.

Early public life[edit]

After his graduation in 1895 Coolidge studied law, was admitted to the Massachusetts bar in 1897, and began to practice in the city of Northampton, where he became active in local GOP politics. In 1898 he was elected to the common council. Thereafter he was seldom out of public office. He was elected to the Massachusetts General Court (legislature) in 1907. After two terms he was elected mayor of Northampton and then was elected to the state senate; during 1914-1915 he was president of that body. He had also served as chairman of the Republican State Committee, and he spent three terms as lieutenant governor of the state.

In 1905 Coolidge married Grace Anna Goodhue of Burlington, Vt. The couple had two sons, John and Calvin, the younger of whom, Calvin, died on July 7, 1924, from blood poisoning.

Governor and Vice President[edit]

When Governor Samuel W. McCall retired in 1918, Coolidge became the unanimous choice of the Republican Party for the governorship; he was elected and took office in January 1919. As governor, Coolidge made no radical innovations nor did he sponsor a legislative program. A conservative, he devoted himself to a program of economy in government. The Boston police strike, and his handling of it, first brought him to national attention. On Sept. 9, 1919, the police struck in protest against the police commissioner's refusal to permit them to join an American Federation of Labor union. Immediately there were riots and disorder. After some urging Governor Coolidge called out the state guard to preserve order and personally took charge. The governor answered Samuel Gompers' objections to his actions with the statement: "There is no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, at any time." The statement received nationwide publicity. After the nomination of Warren G. Harding by the Republican national convention in 1920, the members of the convention rebelled against the dominant senatorial clique. They nominated Coolidge for second place on the ticket after his name had been presented by a comparatively unknown delegate. Coolidge was elected along with Harding in 1920 and became president on Aug. 2, 1923, when Harding died of natural causes. Coolidge was at his father's house in Vermont when the momentous news arrived. His father, a notary public, administered the oath of office.

Presidency[edit]

The elections in 1922 had reduced the party's numbers in Congress to a scant majority. Moreover, the scandals connected with the Harding administration were in the process of being made public by a congressional committee. Yet, a little over a year later, Coolidge was elected for another term by a landslide over both John W. Davis, Democrat, and Robert La Follette, Progressive. Davis got 29% of the popular vote, carrying the South from Virginia to Texas, and 136 electoral votes, LaFollette carried Wisconsin and many German and railroad centers, but Coolidge won easily with 382 electoral votes. Four years later, when he left office, his party was in a much stronger position than it had been in 1924.

Felzenberg shows that Coolidge battled intolerance, lynching and especially the Ku Klux Klan, which lost all its influence during his term.

In 1924 he appointed a commission to investigate the circumstances of the Teapot Dome oil lease, a scandal inherited from the Harding administration. By focusing all the blame on Harding, he permanently tarnished Harding's name and promoted himself.

Economic policies[edit]

Coolidge famously said, "The business of America is business."

The Coolidge policy was a simple one, made easier by the continuous prosperity and the weakness of the liberal opposition. He believed in government economy, reduced taxation, and gave aid to private business without accompanying restrictive regulation. In 1927 he vetoed the soldiers' bonus bill. Coolidge opposed any government control in interstate electrical power and was against the proposal for government operation of the Wilson Dam at Muscle Shoals on the Tennessee River; in 1933 it became part of the New Deal's TVA.

Throughout the farming regions of the traditionally Republican Middle West loud complaints were heard about the farm crisis. It was characterized by low prices for crops and the overhang of the land bubble that burst in 1920, leaving many farmers deeply in debt for new lands they purchased at high price during the war. The farmers wanted the federal government to intervene in the market, by buying crops at high prices and dumping them abroad cheaply. Congress passed the legislation, known as the and the McNary-Haugen Bill, a farm relief bill pushed by Senator Charles McNary of Oregon, but Coolidge vetoed the measure. He supported the alternative program of Hoover and Jardine to modernize farming, by bringing in more electricity, more efficient equipment, better seeds and breeds, and better business practices.

Foreign Affairs[edit]

In the realm of foreign affairs the president urged the nation to become a member of the World Court, but the bill authorizing it was hedged with so many qualifications that the other member nations refused to admit the United States. Under the direction of Secretary of the Treasury Andrew W. Mellon, plans for the payment of foreign government debts to the United States were negotiated and approved. During the Coolidge administration the Kellogg-Briand Pact, renouncing war as an instrument of national policy, was signed by most of the important nations of the world. The appointment of Dwight W. Morrow as ambassador to Mexico did much to restore good relations with that country, although the policy pursued elsewhere in Latin America in the interest of American investors helped maintain the Latin-American distrust of their northern neighbor.

Calvin Coolidge and Prohibition[edit]

Calvin Coolidge was not a teetotaler, but he didn't have much use for alcohol. Due to his belief in limited government, he cut the Prohibition Bureau's budget during the boom year of 1926. Andrew Mellon, who as Treasury Secretary was also the Chief Prohibition Enforcement Officer in the United States, hated the law and was less than dedicated in his enforcement efforts.[1]

Evaluations[edit]

In the short view, the Coolidge administration was a preeminently successful one. Income taxes and corporate taxes were greatly reduced, a major part of the national debt was retired, and the nation experienced some of the most prosperous years in its history. The Coolidge policies were in part responsible for these benefits, but some hostile liberal historians falsely claim they were probably responsible, in part, for the great depression that followed.

Coolidge's image was to a degree shaped by Madison Avenue. Buckley (2003) reveals the role of advertising giant Bruce Barton in the remaking of the public persona or image of Coolidge during 1919-26 and, in so doing, guiding a dramatic shift in politics and the wide acceptance of consumer culture. The dominance of the political party bosses, who selected Harding in 1920, ended when the business elite wrested control from the party, using their ability to raise money for advertising and ultimately commodifying the political process. Members of this elite suggested that Barton refashion Coolidge from an aloof man driven by the advancement of his career into a voice of the masses, the "silent majority," which Barton accomplished with press coverage, exploiting the new technology of radio for political speeches, newsreels, an exclusive "spontaneous" interview with Coolidge, and by arranging events that would be covered free, as news. Coolidge's election to the presidency in 1924 was the first campaign of personality, in which style was promoted over substance, tapping into "intense private longings" of a public uncertain of its moorings in a rapidly modernizing society. Gilbert (2003) and Gilbert (2005) argues that Coolidge suffered from clinical depression throughout his life. Gilbert discusses the major symptoms of the disorder as evidenced in Coolidge's personal and political behavior. He exhibited symptoms from a very early age, beginning with his grandfather's death when he was six and again with the deaths of his mother and sister during his adolescence. Ascending to the presidency in 1923, Coolidge at first was diligent, effective, and respectful of others. After the death of his teenage son in 1924, however, his demeanor and degree of political engagement changed drastically. He developed hypersomnia, sleeping as much as 15 hours per day, and he began to treat White House staffers and his wife rudely, often publicly humiliating them. Moreover, he became far less effective as a decision-maker and grew increasingly detached from political issues.

Other scholars note Coolidge's effective and principled stand against the philosophy of Progressivism. Joseph Postell, for instance, argues that Coolidge presents the most formidable attack on the principles of progressivism of any 20th century conservative.[2] According to Postell, Coolidge's philosophical framework defends both the benevolence of custom as well as the truths of the American Founding. While Coolidge advocated a return to and a protection of America's political tradition, he did so not out of some thoughtless fear of the future, but for the sake of universal truths and the principles of the Declaration.[3] While Coolidge advocated a return to and a protection of America's tradition, he did so in order to best protect the Constitution and natural rights.[4] Coolidge's philosophical thought recognized that human nature is fixed and cannot be remolded by activist government. As he maintained in his inaugural address, Americans "must realize that human nature is about the most constant thing in the universe and that the essentials of human relationship do not change." This is one of the "fixed stars" that Americans must recognize to properly pursue their political future. With the recognition of this essential truth, Coolidge concluded that the only policies to be pursued were those rooted in America's history, traditions, and national identity. "If we examine carefully what we have done, we can determine the more accurately what we can do."

Silent Cal[edit]

A woman once told Coolidge that she had bet someone that she could get him to say more than two words. He told her, "You lose."

"Silent Cal," as Coolidge was known, would allegedly sleep a great deal, both during the day as well as the night. When the liberal satirist Dorothy Parker heard news that he had died, she declared, "How can they tell?"

Retirement[edit]

In the summer of 1927 Coolidge made the statement, "I do not chose to run for president in 1928." He did not indicate his choice of his successor. Coolidge left the White House on Mar. 4, 1929, amid the acclaim of the nation. Returning to Northampton, he published his autobiography and wrote articles for newspapers and periodicals. These and his business activities kept him engaged until his death on Jan. 5, 1933, in the midst of the Great Depression.

Quotes[edit]

- "Nothing is easier than spending the public money. It doesn't appear to belong to anybody."

- "It was never flaunted for the glory of royalty, but to be born under it is to be born a child of a king, and to establish a home under it is to be the founder of a royal house." - Speaking of the American flag

- "I favor the American system of individual enterprise, and I am opposed to any general extension of government ownership, and control."

- when informed that the Army and Navy each wanted a new military airplane, the frugal Coolidge allegedly replied, "Why can't they just buy one airplane, and take turns flying it?"[5]

- "Unfortunately the Federal Government has strayed far afield from its legitimate business. It has trespassed upon fields where there should be no trespass. If we could confine our Federal expenditures to the legitimate obligations and functions of the Federal Government, a material reduction would be apparent. But far more important than this would be its effect upon the fabric of our constitutional form of government, which tends to be gradually weakened and undermined by this encroachment. The cure for this is not in our hands. It lies with the people. It will come when they realize the necessity of State assumption of State responsibility. It will come when they realize that the laws under which the Federal Government hands out contributions to the states are placing upon them a double burden of taxation–Federal taxation in the first instance to raise the moneys which the Government donates to the states, and state taxation in the second instance to meet the extravagances of state expenditures which are tempted by Federal donations." - At Memorial Continental Hall, January 21, 1924

- "What we need is not more Federal government, but better local government."

- "Nations which are torn by dissension and discord, which are weak and inefficient at home, have little standing or influence abroad. Even the blind do not chose the blind to lead them."

- "There is no substitute for a militant freedom. The only alternative is submission and slavery." - Acceptance of the Memorial on Behalf of the Government and People of the United States[6]

- "A very positive echo of what the Dutch had done in 1581, and what the English were preparing to do, appears in the assertion of the Rev. Thomas Hooker, of Connecticut, as early as 1638, when he said in a sermon before the General Court that- “The foundation of authority is laid in the free consent of the people.” “The choice of public magistrates belongs unto the people by God’s own allowance.” This doctrine found wide acceptance among the nonconformist clergy who later made up the Congregational Church. The great apostle of this movement was the Rev. John Wise, of Massachusetts. He was one of the leaders of the revolt against the royal governor Edmund Andros in 1687, for which he suffered imprisonment. He was a liberal in ecclesiastical controversies. He appears to have been familiar with the writings of the political scientist, Samuel Pufendorf, who was born in Saxony in 1632. Wise published a treatise, entitled “The Church’s Quarrel Espoused,” in 1710, which was amplified in another publication in 1717. In it he dealt with the principles of civil government. His works were reprinted in 1772 and have been declared to have been nothing less than a textbook of liberty for our Revolutionary fathers."[7][8]

- "His was the directing spirit without which there would have been no independence, no Union, no Constitution, and no Republic. His ways were the ways of truth. He built for eternity. His influence grows. His stature increases with the increasing years. In wisdom of action, in purity of character, he stands alone. We cannot yet estimate him. We can only indicate our reverence for him and thank the Divine Providence which sent him to serve and inspire his fellow men."[9][10]

- "It is hard to see how a great man can be an atheist. Without the sustaining influence of faith in a divine power we could have little faith in ourselves. We need to feel that behind us is intelligence and love. Doubters do not achieve; skeptics do not contribute; cynics do not create. Faith is the great motive power, and no man realizes his full possibilities unless he has the deep conviction that life is eternally important, and that his work, well done, is a part of an unending plan."[11]

- "Restricted immigration is not an offensive but purely a defensive action. It is not adopted in criticism of others in the slightest degree, but solely for the purpose of protecting ourselves. We cast no aspersions on any race or creed, but we must remember that every object of our institutions of society and government will fail unless America be kept American."[12]

Trivia[edit]

- Coolidge was known to pull pranks on his bodyguards. He would press all his buttons in his office to call his bodyguards to him and would hide under his desk as they frantically looked for him.[13]

Bibliography[edit]

- Buckley, Kerry W. "'A President for the "Great Silent Majority': Bruce Barton's Construction of Calvin Coolidge." New England Quarterly 2003 76(4): 593–626. Issn: 0028-4866 Fulltext: in Jstor

- Felzenberg, Alvin S. "Calvin Coolidge and Race: His Record in Dealing with the Racial Tensions of the 1920s." New England Journal of History 1998 55(1): 83–96.

- Ferrell, Robert H. The Presidency of Calvin Coolidge. U. Press of Kansas, 1998. 244 pp. The standard scholarly study.

- Gilbert, Robert E. "Calvin Coolidge's Tragic Presidency: the Political Effects of Bereavement and Depression." Journal of American Studies 2005 39(1): 87–109. Issn: 0021-8758 Fulltext: in Cambridge and Swetswise

- Gilbert, Robert E. The Tormented President: Calvin Coolidge, Death, and Clinical Depression. Praeger, 2003. 288pp

- Greenberg, David. Calvin Coolidge (2006), short biography. excerpt and text search

- Haynes, John Earl, ed. Calvin Coolidge and the Coolidge Era: Essays on the History of the 1920s. Library of Congress, 1998. 329 pp. essays by scholars

- McCoy, Donald R. Calvin Coolidge: A Biography (1967), 447pp, the standard scholarly biography

- Pietrusza, David 1920: The Year of the Six Presidents New York: Carroll & Graf, 2007

- Pietrusza, David (ed.) Calvin Coolidge: A Documentary Biography

- Pietrusza, David (ed.) Calvin Coolidge on the Founders

- Pietrusza, David (ed.) Silent Cal's Almanack: The Homespun Wit and Wisdom of Vermont's Calvin Coolidge createspace: 2008.

- Shlaes, Amity Coolidge

- White, William Allen A Puritan in Babylon: The Story of Calvin Coolidge, (1938) online edition

Primary sources[edit]

- Calvin Coolidge. The Autobiography of Calvin Coolidge (1929), online edition

- Howard H. Quint and Robert H. Ferrell, eds. The Talkative President: The Off-The-Record Press Conferences of Calvin Coolidge, (1964), 276pp online edition

- Calvin Coolidge Telegram to Samuel Gompers re: Boston Police Strike online edition

References[edit]

- ↑ Water, water everywhere, and not a drop to drink – Coolidge and Prohibition

- ↑ Joseph W. Postell and Johnathan O'Neill, "Roaring Against Progressivism: Calvin Coolidge's Principled Conservatism" in Towards an American Conservatism: Constitutional Conservatism in the Progressive Era, (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013) 183.

- ↑ Joseph W. Postell and Johnathan O'Neill, Towards an American Conservatism, 183.

- ↑ Joseph W. Postell and Johnathan O'Neill, "Roaring Against Progressivism: Calvin Coolidge's Principled Conservatism" in Towards an American Conservatism: Constitutional Conservatism in the Progressive Era, (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013) 183.

- ↑ Joseph Tartakovsky, "The Lives of the Constitution," p. 179 (NY: Encounter Books) (noting that the quote is "probably apocryphal").

- ↑ Report of the Proceedings of the Reunions of the Society of the Army of the Tennessee, Volumes 44-45

- ↑ Calvin Coolidge Challenges Progress in the Name of the Declaration of Independence, Heritage Foundation

- ↑ Speech on the 150th Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence

- ↑ A Joint Session to Commemorate the Birthday of George Washington, February 22, 1927

- ↑ Apostle of Liberty: The World-Changing Leadership of George Washington

- ↑ Telephone Remarks to a Group of Boy Scouts: "What it Means to Be a Boy Scout", July 25, 1924.

- ↑ “Accepting The Republican Presidential Nomination,” on August 14, 1924. As found in The Mind of the President, p. 216-217.

- ↑ https://funfactz.com/funny-facts/calvin-coolidge-bodyguards/

External links[edit]

- excellent essays & documents from Miller Center U Virginia

- Author David Pietrusza discusses Calvin Coolidge on C-SPAN BookTV

- Works by Calvin Coolidge - text and free audio - LibriVox

- Coolidge Foundation

| |||||

| |||||

| ||||||||

Categories: [Republicans] [United States History] [1920s] [Conservatives] [Massachusetts Governors] [Fiscal Conservatives] [Former Governors] [Republican Governors] [Mayors] [Veterans] [Patriots] [Congregationalists] [Non-Interventionist Republicans] [Republican Anti-establishment] [Civil Rights] [Old Right]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/15/2023 12:35:43 | 13 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Calvin_Coolidge | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF